The UK government’s public consultation for their proposed animal welfare labelling scheme[1] closes on the 7th of May. I.e. a week away. If you’re in the UK and care about animal welfare, I think you should probably submit an answer to it. If you don't care about animal welfare, forget you saw this.

In this post I’ll briefly explain what the proposed labelling scheme is, reasons to be hopeful (and cautious), why a public consultation may be unusually impactful, and how to fill in the form. If you’re only interested in the final point, skip to this section. I’ve included a link to a document which provides great suggested answers to make the submission process much easier (I estimate it saved me up to an hour).

PS: I call for out of season Draft Amnesty on this post— I wanted to get it out quickly to give people time to respond to the consultation, so it is a bit sloppy. However, if I say something wrong, correct me!

What is Defra proposing?

Defra, the UK Department for Environment, Food & Agricultural Affairs, is proposing, in AdamC's words[2]:

- Mandatory labelling, which would apply to chicken, eggs and pig products (with the suggestion that beef, lamb and dairy could follow later).

- At least initially, this would not apply to restaurants etc., but to food from retailers like supermarkets.

- At least initially, it would only cover unprocessed and minimally processed foods, so e.g. beef mince and probably bacon, but not meaty ready meals or meringues.

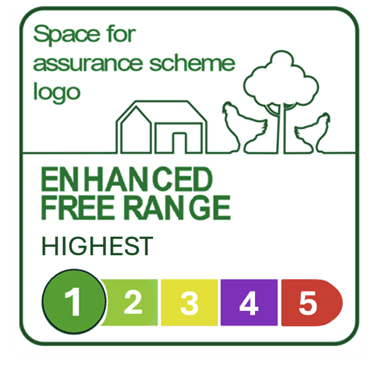

- There would be five tiers "primarily based on method of production", covering types of confinement, enrichment, mutilations, breed and more. Full draft standards can be seen here.

- The tiers might be referred to by numbers, letters or stars, potentially also with names, colours and pictures (see their mock-up below, which I think needs improvement).

- The 2nd lowest tier would simply match UK minimum legal requirements, while the lowest tier would be for "products that are not verified as meeting baseline UK welfare regulations". Ideally, a lot of retailers, with or without encouragement, will not sell the lowest tier products – reducing the prevalence of low welfare imports.

- There is no explicit draft timetable but it suggests an 18 month implementation period after legislation.

According to Compassion for World Farming, Defra “previously promised to consult on mandatory animal welfare labelling in 2023, following a ‘Call for Evidence’ in 2021. Frustratingly, Defra then dropped these plans which they no longer saw as a priority, so we are delighted that after continued campaigning from our supporters – who called on the Secretary of State at Defra to reinstate the promised consultation on honest food labelling – the Government has made a U-turn.”

How promising is animal welfare labelling?

When there is insufficient regulation, animal welfare labelling can be actively harmful. For example, in the US, meat can bear the label “humanely raised” only with sign off from the USDA[3], but “according to experts, those claims aren’t scruticinized closely”.

In the US: “labeling claims such as “ethically/responsibly/thoughtfully raised” have no legal definition and can be used on products that come from factory farms where welfare requirements are no higher than standard practices. In essence, any producer can make these claims.”

This leads to bad outcomes because shoppers in the US care about animal welfare, at least to a degree. They will often select products which suggest higher welfare, even when, in fact, they are buying factory farmed meat.

Products in UK can choose to take part in welfare labelling schemes such as the RSPCA’s[4]. However, this isn’t legally mandatory, and packaging suggestive of higher welfare is still legal. Despite this, consumers seem to want higher welfare meat (see for example, this study which shows a higher willingness to pay for RSPCA assured chicken breasts).

A mandatory, universal labelling scheme with good provisions for monitoring farms could allow consumers to compare across products, and reliably choose higher welfare options. Ideally, a labelling scheme could also be used to nudge, or pressure, supermarkets to stop selling low welfare products.

We have a good case study for the success of labelling schemes in the UK, where the market for free-range eggs has risen form 30% of eggs sold in 2004 when mandatory labelling (free-range, caged hens, barn, organic) was introduced, to 60% in 2023. Plausibly because of this measure, retailers like Waitrose, Marks and Spencers, and Sainsburys no longer sell caged eggs.

How influential are public consultations?

Max Carpendale at Animal Ask wrote up an investigation into this question.

Two relevant takeaways are:

- Where possible, it seems to be valuable to signal expertise in your responses (for example, awareness of counter-arguments).

- In a previous consultation from Defra, on whether the Givernment should ban live transport for animals, the write up of the consultation made heavy use of an “X% of respondents supported Y” framing. This suggests, tentatively, that more responses for this current consultation would be better, perhaps even if they say exactly the same thing.

How to fill in the consultation form.

- Go to this link.

- Fill in the questions based on your own views. This google doc from Ben Stevenson (Rethink Priorities) and Haven King-Nobles (Fish Welfare Initiative)[5] gives sample answers which I found very helpful for writing persuasive and informed answers.[6] The process, with the help of Ben and Haven's doc, took around 30 mins. If you didn't change the wording, it could take much less.

- Let other people know!

- ^

Which I heard about from this post.

- ^

With some minor edits.

- ^

Another good piece on this, from Faunalytics.

- ^

Which Compassion in World Farming reviews fairly favourably.

- ^

Note that this document was written in a private capacity and does not necessarily represent the views of their organisations.

- ^

See this comment thread for some discussion.

Shout out to my Mum for filling in the form.

Hi Toby, thank you so much for writing a comprehensive review for this time sensitive opportunity.

For anyone interested in a different version of the suggested answers that Ben and Haven made that is more aimed at encouraging the adoption of on-farm monitoring systems in order to lay the groundwork for AI analysis for welfare metrics, please see this guide that I just wrote.

Thanks for letting me know about Ben and Haven's doc!

Executive summary: The UK government's proposed mandatory animal welfare labelling scheme for meat products is a promising step that could significantly improve farm animal welfare, and the public consultation is an important opportunity to influence the policy.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.