Epistemic status: amphetamines

Sooner or later, the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.

— V.S. Pritchett

EA produces much talk about an obligation to donate some or even most of your wealth. In both direct work and earning to give, there's a connection between your work productivity and your (direct or indirect) impact. Hard work is also a costly signal of commitment that could substitute for frugality in our less funding-constrained phase of the movement. And working incredibly hard increases the chance of tail successes that might generate very high impact.

In the same way that you might want to attract converts by advancing a softer norm of donating only 10% of your income rather than everything above $40k, you might want to create a softer norm about productivity, and not feel bad about only following this norm. This post is addressed instead to those who haven't considered much at all the prospect of experimenting with working 60 hours a week rather than 30-40.

Don't dismiss this option out of hand because of general concerns about burnout. There are multiple good reasons to think you should work much harder.

First, the short-term optimal workweek might just be very long. Studies often find that CEOs work 50+ hours per week. Silicon Valley is very productive and has a "hustle culture" involving long work hours (see also). I agree with Lynette Bye that most of the working hours literature is poor—I'm even more skeptical than she is about agenda-driven research on Gilded Age factory workers—and that gaining an impression from anecdotes of top performers is better. Top performers in business routinely work long hours, and reading through lists of anecdotes like Daily Rituals (which is mostly writers and artists) you'll see a lot of strict routines, long hours, and stimulants of all kinds: caffeine, nicotine, amphetamines.

High-performing managers in the EA ecosystem report working long hours:

- "I know there have been some pretty publicized debates recently in Silicon Valley about whether you can have it all and be successful and have balance, or whether you really do need to almost work yourself to death in order to accomplish something big. At least in our mind and our experience with our company is that sometimes if you want to do something that is very challenging and that you think will have a big impact and hasn’t been done before the reality is you just have to run and work harder and faster than anyone else and I think that’s a very real thing for us. We have gone all-in on this." -Theresa Condor, COO at Spire Global

- "Yeah, so the limiting factor is I only want to work about 55 hours a week or something like that at the most. And so maybe I'll experiment in pushing that up to 60. But somewhere between 45 and 60 hours a week. That is hours in the office, and that transfers into Toggl hours at a rate of something like 75% to 85% just because of pee breaks and chatting to people and eating and stuff like that. And so that translates into around 40 Toggl hours, like 35 to 40 Toggl hours a week. And then, then the fraction of those that are spent on key priorities. The rest of it is meetings with people and emails, which are the two biggest sucks of time. Also internal comms, which is checking Slack or recording my goals and stuff like that." -Niel Bowerman, Director of Special Projects at 80,000 Hours

However, productive hours look more limited for certain types of cognitive or intellectual work:

- "I've done several different kinds of work, and the limits were different for each. My limit for the harder types of writing or programming is about five hours a day. Whereas when I was running a startup, I could work all the time. At least for the three years I did it; if I'd kept going much longer, I'd probably have needed to take occasional vacations." -Paul Graham

- "I think probably ten versus eight hours, all things considered, it's not clear they're valuable at all. Maybe, let's say the first three hours are like two thirds the value of the whole eight-hour day. And then, especially if I'm working six days a week, I'm not convinced the difference between eight and ten hours is actually adding anything in the long term." -Will MacAskill

- "One way that I think about it is that the most you can increase your output from working harder is often around 25%. If you want to increase your output by 5x, or by 10x, you can't just work harder. You need to get better at skipping things, deciding what not to do, deciding what shortcuts to take." -Holden Karnofsky

- Bonus: a really long list of writers' work habits

So if you're interested in some kind of intellectual research (arguably a majority of 80k Hours's priority paths) then this experiment might be less worthwhile, but if you're working in operations, entrepreneurship, or community-building then it could provide valuable information about your work capacity.

Karnofsky's quote also presents the challenge that if you work normal hours, someone else can work twice as many hours as you but not three times as many. This isn't even half an order of magnitude, so you might expect work hours to be unimportant relative to working on the right problems.

This leads us to the second reason to think you should try working harder, which is that—especially early in your career—working more hours has superlinear returns because it increases the growth rate of your career. This can be true even if your short-term productivity stagnates or decreases. A good take on this: "One extremely under-rated impact of working harder is that you learn more. You have sub-linear short-term impact with increasing work hours because of things like burnout, or even just using up the best opportunities, but long-term you have super-linear impact (as long as you apply good epistemics) because you just complete more operational cycles and try more ideas about how to do the work."

A third reason is that burnout risk might be overrated if most of your impact comes from the small chance of you being a very high performer, perhaps because being 99th percentile is 100+ times better than being 90th percentile. This makes studying the habits of top performers even more useful because the survivorship bias is less important.

Addendum: stimulants

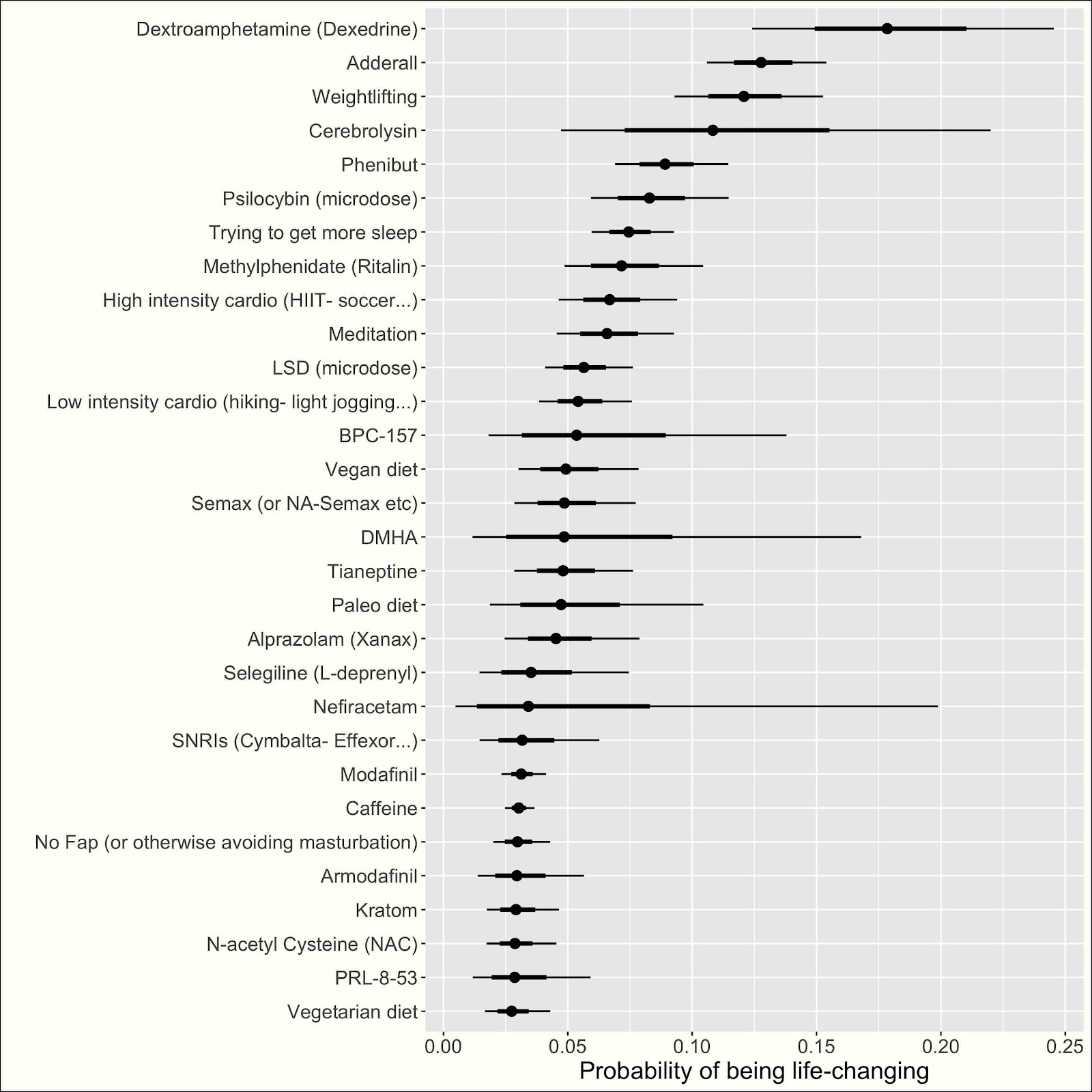

Consider this large nootropics survey and the metric "probability of life-changing effect":

Famous intellectuals, artists, and statesmen throughout history often took stimulants, sometimes in copious amounts. Silicon Valley culture has a similar reputation. Besides lifestyle interventions like lifting weights (12% chance of a life-changing effect), sleeping more, and running, there could be huge information value from experimenting with modafinil or amphetamines like Adderall (12.5% chance) just from a modest probability of a life-changing effect. If your AI timelines are long enough, you should consider long-term health effects: Scott Alexander wrote in 2017 that Adderall risks resemble “the risks of eating one extra strip of bacon per day.”

I encourage readers to consider whether they are the correct audience for this advice. As I understand it, this advice is directed at those for whom all of the following apply:

- Making a large impact on the world is overwhelmingly more important to you than other things people often want in their lives (such as spending lot of time with friends/family, raising children, etc.)

- You have already experienced a normal workload of ~38h per week for at least a couple of years, and found this pretty easy/comfortable to maintain

- You generally consider yourself to be happy, highly composed and emotionally stable. You have no history of depression or other mood-related dissorders.

If any of these things do not apply, this post is not for you! And it would probably be a huge mistake to seek out an adderall prescription.

Even if all those things apply ... this post may not be for you! Last year I tried to replace sleep with caffeine, and it did not go well. Even if you think you're happy and emotionally stable, you may discover that stimulants are anxiogenic for you, and you may be dumb enough (i.e., me) not to make that connection for a year.

Stimulants, at least for me, are much better at making me feel productive than increasing my total output. I regularly wasted 3-6 hours chunks plumbing the depths of a rabbit hole that unstimulated me would have rightly avoided. A moderate caveat emptor here.

I’m not convinced you can really replace sleep with caffeine in any meaningful way; tolerance to caffeine builds so quickly as to make it unuseful after a couple of weeks.

...unless you have other reasons to believe that an Adderall prescription might be good for you. Saliently: if you have adhd symptoms.

If you're not the right person for the article, I'd instead recommend this post on Sustained effort, potential, and obligation. I've found it's given me a helpful framework for making sense of my own limits on working hours, and you may also find it useful.

I admit that reading this post also stirred up some feelings of inadequacy for me—because, unlike all those CEOs and great men of history, I have actually a pretty low-to-average limit on how much sustained effort my brain will tolerate in a day. If you find yourself with similar feelings (which might be distressing, perhaps even leading you to spiral into self-hatred and/or seek out extreme measures to 'fix' yourself), the best antidote I've found for myself is The Parable of the Talents by Scott Alexander. (TLDR: variation in innate abilities is widespread, and recognizing and accepting the limits on one's abilities is both more truthful and more compassionate than denying them.)

Some stimulants seem to work well for depression, however: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6375494/

I think there's conflicting pieces of evidence on this topic, and most recent studies focus on stimulants as add-ons to antidepressants, rather than as the primary treatment for depression.

So, if you think you might be some level of depressed (without having ADHD), I think it's sound advice to avoid fixating on stimulants as your most promising option—but know you do have lots of effective options to try that might really improve your wellbeing and productivity, such as those discussed here and described by community members here and here.

Good point about stimulants mostly being useful as adjuncts and not as monotherapy.

I'd be careful with this sort of advice.

All I have to offer is my personal story which is of course very little evidence (though I've seen similar stories play out among many of my friends and colleagues). I'll first talk about my experience with stimulants and then about my experience with pushing myself to work more.

In my mid twenties I basically followed the same sort of logic and started taking amphetamines (very reasonable dosages, not more than twice a week). Every skeptic I told, among other things, the story of Paul Erdős who took amphetamines practically every day for decades and was perhaps the most productive mathematician ever. (In fact, Erdős was so productive that his friends created the widely used Erdős number which "describes a person's degree of separation from Erdős himself, based on their collaboration with him, or with another who has their own Erdős number.")

Well, for me personally this worked for a few months after which side effects started to slowly show up (low mood, fatigue, insomnia, etc.). It was so gradual that I needed another few months to attribute them to amphetamines. It was also very much unlike how I expected side effects and withdrawal to manifest. It's (for many people) not this immediate thing that happens after the first time you take amphetamines. It's usually more gradual than that. Several of my friends also experimented with amphetamine for productivity-enhancing effects, for none of them it turned out positively.

That being said, I've had somewhat better experiences with Ritalin (though I still often wonder whether it was net positive). And I made much better experiences yet with MAO inhibitors like tranylcypromine (which still have lots of side effects). (I might write more on this in the future.)

Regarding pushing yourself to work more: I think in my case this backfired extremely hard and caused me to burnout. In my twenties I always had this suspicion that talk about burnout is widely exacerbated, perhaps especially by lazy or selfish people who want to work less. (I was pretty stupid.) In my experience, especially if you are a researcher, pushing yourself hard doesn't work that well, at least not in the long term. Your best ideas are probably two orders of magnitude more important than your average idea. If you start caring primarily about how many hours you work, you risk working on ideas that are easy to write about or execute. Coming up with good ideas often doesn't look like work at all. You might just be reading for your own pleasure or out of curiosity. That's at least how it worked for me. (As an example, I've had most of the core ideas for this article after I had reduced my working hours substantially.)

I guess if you have (very) short timeline, are generally quite young, healthy and robust, I'd be much more optimistic about such strategies. And as the case of e.g. Erdős shows, outliers do exist.

Would be interested in your experience with tranylcypromine; it sounds to me to be way more dangerous than amphetamines.

Agree with Xavier's comment that people should consider reversing the advice, but generally confused/worried that this post is getting downvoted (13 karma on 18 votes as of this writing). In general, I want the forum to be a place where bold, truth-seeking claims about how to do more good get attention. My model of people downvoting this is that they are worried that this will make people work harder despite this being suboptimal. I think that people can make these evaluations well for themselves, and that it's good to present people with information and arguments that might change their mind. Just as "donate lots of your money to global charities" and "stop buying animal products" are unwelcome to hear and might be bad for you if you take them to extremes in your context but are probably good for the world, "consider working more hours" could be bad in some cases but also might help people learn faster and become excellent at impactful work, and we should be at least be comfortable debating whether we're at the right point on the curve.

I agree that the forum should be a place for bold, truth-seeking claims about how to do more good. However, I think recommending people try taking stimulants is quite different to recommending people try working longer hours. The downside risks of harm are higher and more serious, and more difficult for readers to interpret for themselves. I don't think this post is well argued, but the part on stimulants is particularly weak.

Working more hours could help learning in the sense of helping you collect data faster. But if you want to learn from the data you already have, I'd suggest working fewer hours (or taking a vacation) to facilitate a reflective mindset.

I had a friend who took a stimulant every day, working at a startup, only to wake up many months later and realize the startup wasn't going anywhere & he'd wasted a lot of time. Beware tunnel vision. Once you're at 40 hours a week, it's generally more valuable to work smarter than work harder IMO.

I am worried about relying on anecdotes of top performers as this has an obvious selection effect neglecting the (probably sizeable) group of people that tried stimuant-driven work binges and simply burned out.

This is hand-wavingly addressed later

First, I think it seems unattractive to me to have EA become a large group of amphetamine-fueled workaholics with high burnout rates - not even because of optics, but because of the immense suffering of those that will burn out.

Secondly, this neglects how many of the high-impact performers would have been high-impact absent amphetamines or excessive working hours.

Third, it strikes me as implausible that the "99th percentile is 100+ times better than being 90th percentile" for the target groups of "operations, entrepreneurship, or community-building ". I did a tad of community-building myself, and would be very surprised if for a community-builder, adding 20 hours of work a week even approximates the value of the first 40 hours spent on community-building, and honestly shocked if it outsized it by a factor of 100.

Lastly and most importantly, it is entirely unclear to me in what relation the "small chance of being a very high performer" and the "chance of burnout" is. It seems entirely plausible to me that the chance of me becoming Erdos-like because I take stimulants and work a ton is thousands of times less likely than the chance that I'll burn out because I take stimulants and work a ton.

I also generally think that health-related advice that goes against widely-held priors should at least attempt to quantify risks and benefits using actual numbers, rather than waving hands.

I like the emphasis on working hard and I think working longer hours is good. Something happens when you start working 60+ hours a week where (in my experience) you begin to have blinders to everything else outside of that work.

For me it becomes the only thing I think about for weeks on end, and it becomes something in my life that I’m subconsciously working on even when I’m not doing the task. Like the mathematician who gets the answer to a proof she’s working on when swimming laps at the pool.

But I’m very very pessimistic about hard stimulants. Nicotine, caffeine, adderall, etc have diminishing returns and tolerance increases the dose required to get the originally stimulating effects. We have heard it before but it is worth mentioning. I would not mentor my bright 16 year old cousin to become reliant on any stimulant.

Weight lifting is underrated. Consciously placing yourself in positive environments is underrated. Maintaining strong mutually beneficially relationships is underrated. And eating a wide variety of fruits and vegetables is underrated.

Do you still do the latter when you are in a 60+ h/week period?

Yea absolutely. It takes planning and discipline but you can go to the gym after a 10 or 12 hour work day. occasionally having dry snacks like nuts or Clif bars helps when working 50-60 hours. I like picking up fruits from the store every third day or so.

I think the wheels come off at 70+, and the type of work that can be done for 70+ hours is probably work that isn’t cognitively demanding.

50-68 hours is my sweet spot where I don’t compromise my diet and I can workout 4 times a week

I am impressed and wish I could do that!

This may not apply to highly intellectual or creative work (as in David__Althaus' comment), but I don't have that kind of job. Tunnel vision is still a potential downside, but that may be mitigated by devoting a part of your work time to maintaining your epistemics.

You should mention that this graph is not from academics testing nootropics on a random sample, but self-reported from nootropics users. So it is non-random, uncontrolled, and unblinded.

The survey also had probabilities of side effects. Maybe include those? A cost-benefit analysis really should also include the potential costs, and not just the potential benefits.

This post with its comments is a valuable discussion.

The post on its own with its lack of cautions and provisos is potentially harmful to many readers, and high upvotes may lead readers to trust it too much. Strong downvote for these reasons.

I'd say the largest problem is I see the red flag of selection bias and using anecdotes and intuition as reliable evidence. This is dangerous, even though I agree with the takeaway that risks should probably be taken.

It is really unfortunate that the existing evidence about work hours as mentioned in Lynette's post is so weak and we need to make decisions based on anecdotical evidence because there is nothing better. It seems to me quite an important topic to study and I wonder why it is not happening.

Maybe it's just really hard to study properly but even then it might be worth it.