In 2023, the top 20 donors to GiveWell gave more than the other 31,890 donors combined. These donors gave at least $1 million each with a mean of $5.87 million.

With stats like these, I mostly view the 10% pledge as a social commitment device rather than a sensible rule for how much to donate. One can think of the 10% pledge as requiring people to give up a constant amount of personal utility under logarithmic utility of consumption. But this doesn't make sense; one should obviously give up more utility if beneficiaries gain more per unit you sacrifice. [1][2]

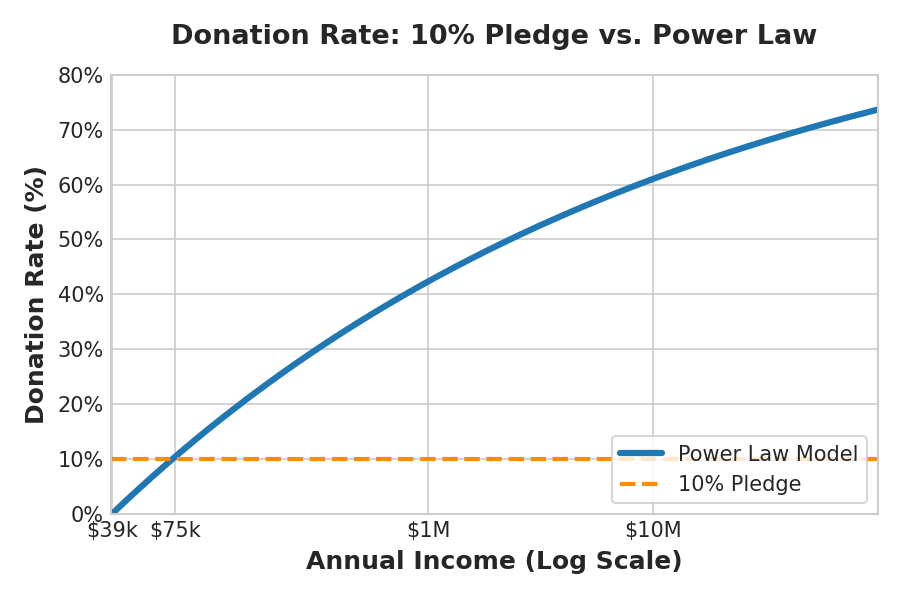

Is there something better that captures the extreme variance in salary these days, eg with junior AI engineers earning >$1M/year? I propose a power law where someone with income Y should donate everything except a consumption budget . Then the donation rate is calculated as .

With parameters somewhat arbitrarily set such that the median American household (income $75K) donates 10% and someone with $10M income donates 60%, we get and γ ≈ 0.83, meaning that every 1% increase in income allows you a 0.83% increase in consumption. We get the following table, which seems pretty reasonable:[3]

| Income | Donation Rate | Donation $ | Consumption $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤$39.3K | 0% | 0 | ≤$39.3k |

| $50K | 3.7% | $1,872 | $48,128 |

| $75K | 10.0% | $7,500 | $67,500 |

| $100K | 14.2% | $14,190 | $85,810 |

| $150K | 19.8% | $29,651 | $120,349 |

| $200K | 23.5% | $47,006 | $152,994 |

| $500K | 34.3% | $171,406 | $328,594 |

| $1M | 41.4% | $414,135 | $585,865 |

| $5M | 55.1% | $2.76M | $2.24M |

| $10M | 60.0% | $6M | $4M |

| $100M | 72.7% | $72.7M | $27.3M |

The difference between $10-100M earners donating 10% vs 60-70% is immense. If the 2023 numbers were from high earners donating 10%, this tiny group going up to 65% would 3.75x total donations; if they were at 65% already, going down to 10% would basically halve GiveWell's revenue.

There's another interpretation of this power law. In economics, different goods have different income elasticities of expenditure, with necessities having γ 0, "normal" goods γ < 1 and "luxury" goods γ > 1. We can interpret the policy of γ = 0.83 for aggregate consumption as asking people to forego none of their necessities, some near-luxury γ 0.83 goods, and a large proportion of luxury γ > 1 goods as their income increases. For some concrete examples, I had Claude generate this table from the empirical literature:

Category Elasticity Range Source Housing (renters) 0.2–0.4 0.19–0.5 RAND/HUD, NBER Food at home (groceries) 0.3–0.4 0.2–0.5 Various US studies Tobacco 0.4 0.3–0.5 Wikipedia Housing (owners) 0.5–0.7 0.36–0.87 Mayo review, Harmon 1988 Food away from home 0.7–0.9 0.5–1.1 USDA ERS Clothing & footwear 0.8–1.0 0.7–1.1 USDA ERS cross-country; US footwear study Gasoline 0.8–1.0 0.66–1.26 Wikipedia summary of studies Transportation 0.95–1.0 0.8–1.1 USDA ERS high-income Education 1.0–1.1 0.9–1.2 USDA ERS Healthcare/Medical 1.2–1.4 1.0–1.6 USDA ERS (US = 1.21) Recreation/Entertainment 1.4–1.5 1.2–1.8 USDA ERS high-income Air travel/Tourism 1.2–2.1 0.6–2.5 Meta-analyses Interpretation

The rough correspondence suggests γ = 0.83 is asking for sacrifice at the "nice-to-have, not need-to-have" margin, which seems ethically defensible.

- ^

Utility of consumption is probably sublogarithmic at the high end, but we'll disregard this.

- ^

The other extreme would be everyone donating all their income down to a flat rate, equal to the consensus selfish:altruistic utility ratio. One of many issues is that this removes all selfish incentive to earn more.

- ^

I forgot to account for taxes because I wrote this up in about an hour, but it shouldn't be too far off