TL;DR: The same business is worth more under charitable ownership. Stakeholders prefer companies whose profits go to charity, and in managerial capitalism, changing ownership doesn't change operations. You get the preference advantage without the operational tradeoffs of other ethical models. For this to be false, something strange would have to happen between documented preferences and market behavior. The downside of testing is bounded; the upside could redirect trillions to solving humanity's biggest problems.

Author’s Note: For years I've been arguing that businesses owned by charities should outperform conventional ones, and compiling the evidence to support it. The current version is here; I'm still refining it and will post it as a standalone shortly. I recently gave the thesis a name, so we don't have to keep repeating a full sentence: the Charitable Ownership Advantage, or COA. This essay lays out why COA matters if true, and why it would be strange if it weren't.

The Charitable Ownership Advantage: Strange if Not True

Most world-changing proposals come with caveats: "This is speculative, but..." or "Despite long odds..." or "We acknowledge the uncertainty, however..."

The Charitable Ownership Advantage thesis is in the opposite position. Based on standard market mechanics and human psychology, the default prediction is that it works. The strange outcome would be if it didn't.

The Thesis

A Profit for Good (PFG) business permanently commits its profits to charitable purposes through durable ownership structures: foundation ownership, charitable trusts, locked-in bylaws, or similar arrangements. The commitment is structural, not discretionary.

The Charitable Ownership Advantage (COA) thesis makes a specific, testable claim:

The same business is worth more under charitable ownership.

Not a different business. Not a business that operates more ethically or sources more sustainably. The same business - same products, prices, operations, management- generates higher margins when owned by a charitable foundation than when owned by private investors.

The mechanism: all else being equal, stakeholders prefer businesses whose profits serve charitable purposes. Customers choose them. Employees accept less to work for them. Media amplifies them. Suppliers favor them. These preferences create competitive advantage without the operational tradeoffs that burden other ethical models, because the advantage operates at the ownership layer, not the operations layer. The stronger and more credible the charitable commitment, the larger the advantage.

If COA is true, the implications are structural. If COA is false, something strange is happening, because the preferences themselves are documented everywhere. For COA to fail, those preferences must somehow evaporate at the point of action.

The Intuitive Case

Start with a simple question:

Given two equivalent options, same price, same quality, same convenience, would you rather your money enrich anonymous shareholders or help solve real problems?

That isn't a hard question.

Now ask the same about work:

Given two equivalent jobs—same role, same pay, same trajectory—would you rather your labor generate profits for distant shareholders or for charity?

Also, not hard.

Run it across stakeholders:

- Customers prefer their purchase to do good.

- Employees prefer their effort to matter.

- Suppliers and partners prefer working with organizations that improve the world.

- Lenders prefer stable, trusted businesses with durable relationships and lower risk.

The answers are consistent. People prefer the option that helps.

The only question is whether this preference, which clearly exists, becomes competitive advantage when a company can offer it with credibility and low friction. COA says it should. And it's not obvious why it wouldn't.

Why Preference Creates Advantage

Stakeholder preferences drive business outcomes. This is not controversial. It's the foundation of branding, employer reputation, supplier relationships, and credit risk assessment.

When stakeholders prefer you:

Customers are easier to acquire and more likely to stay. Acquisition costs fall. Lifetime value rises.

Employees are easier to recruit and more likely to remain. They may accept below market-rate compensation for mission-aligned work while showing higher engagement and lower turnover. Institutional knowledge accumulates.

Suppliers and partners extend favorable terms, provide better service, prioritize your account. Input costs fall or quality rises.

Media finds your story more interesting. Earned coverage substitutes for paid advertising. Marketing efficiency improves.

Lenders see stable revenue, lower turnover, stronger community relationships, all markers of reduced risk. Cost of capital falls.

None of these needs to be dramatic. Most businesses operate on relatively thin margins. And that's the point.

The Margin Leverage Effect

A small improvement in a business does not produce a small improvement in outcomes.

If you operate at a 10% net margin and improve your margin- by some combination of increasing revenue or reducing cost- by 10 percentage points through slightly higher conversion, slightly lower churn, slightly better retention, slightly better terms, profit doesn't increase by 10%. It doubles.

COA, even a large difference in profitability, doesn't require miracles. It requires a set of small, plausible advantages that stack. Modest effects, applied across the margins at which businesses operate, compound geometrically.

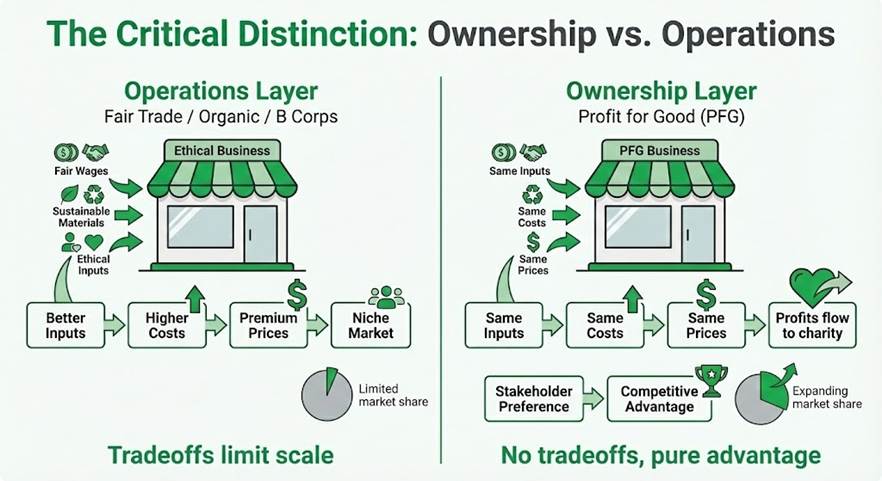

The Critical Distinction: Ownership vs. Operations

Why should this succeed where other "ethical business" models have remained niche?

Most ethical models (Fair Trade, sustainable sourcing, premium wages) operate at the operations layer. They change how the business runs, creating tradeoffs: stakeholder appeal comes with higher costs, limiting scale. Fair Trade remains ~5% of coffee. Organic is ~6% of food. Paying more for ethical products stays niche.

COA operates at the ownership layer. Nothing changes about operations. A PFG company sells the same product at the same price with the same cost structure. The only difference is who owns the business.

Because there's no operational tradeoff - no costlier inputs, no premium pricing, no reduced efficiency- the stakeholder preference creates pure advantage rather than just offsetting higher costs. There is no 'ethical tax.’

Why Strong COA Is the Default Prediction

COA could come in two versions:

- Weak COA: The advantage exists in some sectors but not others. Sector selection determines whether any advantage materializes.

- Strong COA: The advantage is general across most business types. Sector selection affects magnitude, not existence.

Strong COA is what the mechanism predicts. Weak COA is the version that would need special explanation.

Why? Because the preference operates on where profits go, not what the business does.

A person buying coffee and a person buying software are the same person. They have the same values, the same preference for their money to do good. Why would that preference activate for coffee but not software?

An employee at a consulting firm and an employee at a manufacturing plant both want their work to matter. Why would mission affect retention in one industry but not the other?

What varies by sector isn't the preference itself. What varies is whether the preference activates:

- Visibility: Is the ownership structure clear at the point of decision?

- Credibility: Do stakeholders trust the claim and the lock?

- Salience: Does the market culturally notice and reward it?

- Parity feasibility: Can the company compete on price and quality?

This last factor deserves emphasis, because it's where skeptics often retreat: "All else is rarely equal in real markets."

True, but this objection proves too much. All else is rarely equal for any competitive advantage. Brand preference doesn't operate in "all else equal" conditions. Price advantages don't exist in a vacuum of otherwise identical options. Every marginal advantage operates in messy markets where many factors vary simultaneously.

The preference for charitable ownership doesn't vanish when products differ on other dimensions. It's one factor among many, just like brand, price, quality, and convenience are each one factor among many. It always contributes to the calculus. And in markets where other differentiators are weak, it can become the differentiator.

That's not a refutation of COA. It's how competitive advantages work. They matter everywhere; they matter most where alternatives are hardest to distinguish on other grounds.

These are activation factors (execution challenges) not differences in underlying human preference.

For Weak COA to be true, you'd need a story like: "People care whether profits go to charity when buying event tickets but become indifferent when buying accounting software." What would that story even be?

Strong COA not being true would require human preferences to be inconsistent in ways that don't make sense. That would be strange.

What Would Have to Be True for COA to be False

For COA to work, four conditions must hold:

- Stakeholders prefer charitable ownership at parity. Given equivalent options, people would rather their money, labor, or business relationships benefit charity than enrich anonymous shareholders.

- Changing ownership doesn't change operations. A business owned by a charitable foundation can operate the same as one owned by private investors: same products, prices, costs, management.

- Stakeholder preferences affect business outcomes. When customers, employees, suppliers, and lenders prefer you, it shows up in conversion rates, retention, terms, and cost of capital.

- Small advantages compound through margin leverage. On thin margins, modest improvements in revenue or cost produce outsized effects on profit.

A skeptic needs to break only one link. But each is unusually robust:

"Stakeholders don't actually prefer it."

Both stated and revealed preferences say otherwise.

In surveys, overwhelming majorities across countries report preferring ethical options at parity. More importantly, field experiments show people act on this preference: 5-20% sales lifts for charity-linked products at equal prices, 4-7% wage flexibility for mission-aligned work, measurably lower turnover at purpose-driven organizations.

The usual skepticism about stated preferences, i.e., "people say they'd donate but don't", doesn't apply here. Donating requires sacrifice. Choosing a PFG product at the same price requires none. When expressing a prosocial preference costs nothing, stated preference should predict behavior. The gap between what people say and what they do closes when you remove the tradeoff.

"Changing ownership changes how the business operates."

This may have been true a century and a half ago, under a version of capitalism where owners managed their own businesses. It's not true now.

Modern capitalism separated ownership from control. Shareholders are passive. Outside of startups or very small business contexts, the people who run businesses are professional managers compensated through salary and bonuses, not equity. They don't know who owns the shares. They don't care.

Ownership changes happen every day across global stock markets. Shares transfer between pension funds, index funds, private equity, individual investors. And nothing about operations changes. If ownership transfers don't affect operations when shares move between Vanguard and BlackRock, why would they affect operations when shares move to a charitable foundation?

The ownership layer is already decoupled from the operations layer. You can change who receives the profits without changing anything about how those profits are generated.

"Preferences don't affect business outcomes."

This would overturn everything we know about markets.

Brands exist because customer preference matters. Employer reputation exists because employee preference matters. Supplier relationships exist because partner preference matters. The entire edifice of marketing, HR, and credit risk assessment assumes preferences drive outcomes.

A softer version of this objection: "All else is rarely equal in real markets. Other factors dominate." But this applies to every competitive advantage. Brand preference doesn't operate in "all else equal" conditions. Price sensitivity doesn't require identical products or services. Every marginal advantage operates in messy markets where many factors vary simultaneously.

The question isn't whether perfect identicality exists. The question is whether options are close enough that preference tips the balance. In commodity products, fragmented industries, professional services, B2B procurement, parity is common enough. That's not a defeater. It's a targeting insight.

If stakeholder preferences didn't translate to business results, most of what companies spend on reputation, culture, and relationships would be wasted. The skeptic who denies this link isn't just doubting COA; they're doubting market economics.

"Small advantages don't compound."

This is arithmetic. Many businesses operate on margins of 5-15%. A 5-percentage-point improvement in margin doesn't improve profit by 5%—it can double it.

COA doesn't require miracles. It requires a set of modest, plausible advantages- slightly higher conversion, slightly lower churn, slightly better terms, slightly cheaper capital- that stack across the P&L. The math does the rest.

The skeptic has four targets. Each is well-fortified. To defeat COA, identify which link breaks and explain why. Vague skepticism isn't enough—the mechanism is too straightforward. Something specific has to fail.

The Evidence Base

COA is not yet proven at scale. My claim is that it's well past the plausibility threshold and merits serious testing.

Stated preference research shows overwhelming majorities favor ethical options when value is comparable. This holds across countries, demographics, and product categories.

Revealed preference studies show people act on it. Field experiments document 5-20% sales lifts for charity-linked products at price parity. Employee research shows 4-7% wage flexibility for mission-aligned work and substantially lower turnover.

Adjacent models point in the same direction. B Corps show higher survival rates. Foundation-owned companies show lower default rates and better loan terms. The patterns are consistent.

Some businesses have deliberately activated COA—and generally succeeded. Humanitix competes against Ticketmaster and Eventbrite while donating 100% of profits. Thankyou built a consumer goods brand on charitable ownership. Ecosia runs a search engine on it. Newman's Own has donated over $600 million while competing in mainstream retail for 40 years. These aren't controlled experiments, but they're proof of concept: businesses can foreground charitable ownership and win.

Others prove compatibility without activation. Bosch, 94% foundation-owned, runs a €91 billion industrial conglomerate. The Nordic industrial foundations compete globally. These companies deliberately don't emphasize their charitable structure—they compete as normal businesses. This proves charitable ownership is at minimum consistent with competitive performance.

What makes this possible is the shift to managerial capitalism. A century ago, many owners managed their businesses directly—ownership identity affected operations. Today, most business ownership is passive. Shareholders have nothing to do with management. The people who run the business are professional managers compensated through salary and bonuses, not equity.

This separation is usually framed as a problem (agency costs, short-termism). But it's precisely what makes COA viable: if ownership is already operationally irrelevant, then changing who owns the business—from private shareholders to charitable foundations—changes nothing about how it runs. You get the stakeholder advantages of charitable ownership without operational disruption.

What's missing isn't proof of concept: it's rigorous measurement. How large is the effect? Which channels matter most? Where does it activate strongest? That requires instrumented acquisitions with baselines and controls.

Why Hasn't This Been Exploited?

If COA is likely true, where are all the PFG companies?

The answer is a historical categorization error.

Philanthropy conceptualized its role as giving money away, not deploying capital into businesses that profit more by giving it away. For over a century, the model has been to accumulate wealth, then donate it (or invest it and donate the returns).

Conventional capital couldn't exploit COA because capturing the advantage requires sending profits to charity. The moment you redirect profits to private shareholders, you lose the structural feature that creates the advantage.

So philanthropic capital didn't think of charitable identity as a competitive advantage—foundations own plenty of businesses, but as investments that happen to be held by a charity, not as a way to leverage that charity's appeal with stakeholders. And conventional capital couldn't access the advantage if it tried. The opportunity sat unexploited—not because it doesn't work, but because no one with the right capital and the right framing was looking for it.

The conventional path also had natural advantages that made it the default:

Flexibility. Invest now, donate later. You retain options. You can change your mind, shift priorities, decide how much to give and when. Foundation-owned businesses lock in the commitment permanently.

Cause selection. Normal giving lets you fund whatever you want—your alma mater, your local community, your preferred cause, whatever matters to you. PFG structures benefit most when the charitable beneficiary has broad appeal—causes stakeholders recognize and care about.

Without a compelling reason to try something different, why would anyone deviate from the familiar path? Legal structures that enable this—purpose trusts, charitable LLCs, donor-advised arrangements—have existed for decades. Structure isn't the bottleneck.

COA could have been exploited a century ago. It just wasn't.

The Implications If True

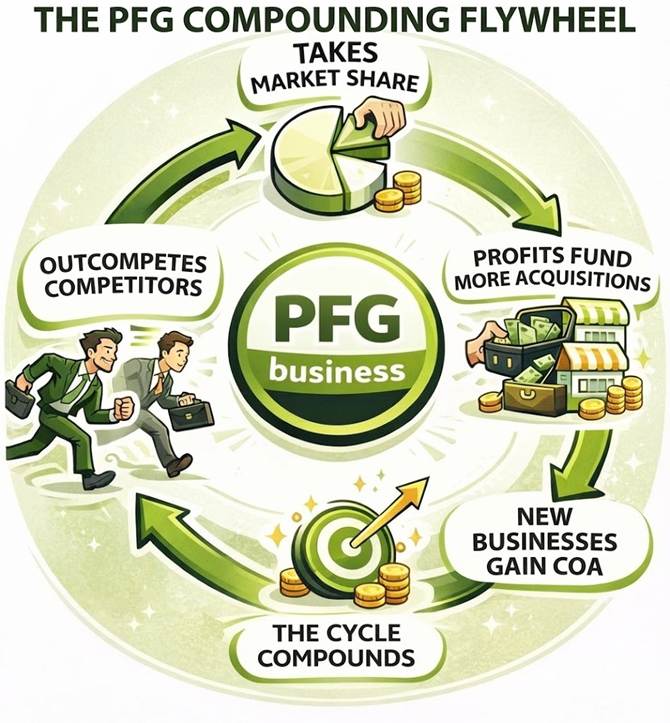

If COA is true, this isn't "better philanthropy." It's a mechanism for competitive displacement.

Follow the logic:

- PFG businesses outcompete conventional competitors.

- They take market share.

- Their profits fund acquisitions of more businesses.

- Those businesses also benefit from COA.

- The cycle compounds.

In the limit: charitable ownership expands because it is competitively superior—not because anyone is forced.

Credit markets accelerate the process. If PFG businesses demonstrate lower risk—more stable revenue, lower turnover, stronger stakeholder relationships—lenders will compete to fund them. Philanthropy can borrow at 4-8% to acquire businesses generating ordinary returns. If COA improves margins by even a few percentage points, the spread over borrowing costs funds further acquisitions. If COA shows up in valuations, you borrow against appreciated assets and redeploy. Capital multiplies.

The constraint shifts from generosity to capital deployment. Traditional philanthropy depends on convincing people to sacrifice. That's hard, slow, and fights human nature. Charitable giving as a share of GDP has been flat for decades.

If COA is true, the limit becomes how fast philanthropic capital recognizes and deploys into this opportunity. The businesses themselves already have operators—professional managers paid through salary and bonuses, not equity. Changing ownership doesn't change who runs them. You need acquisitions professionals to source and execute deals, but the operational talent is already in place.

The ceiling on solving humanity's problems lifts from "how much can we convince people to give away?" to "how fast can we deploy capital?" If strong COA is proven, the capital will follow—lenders will compete to fund lower-risk assets with stable returns and an impact story. The bottleneck becomes deployment speed, not capital availability.

The first constraint fights human nature. The second solves itself.

Why This Is Realistic

"Charity taking over the economy" sounds like revolutionary utopianism. But the mechanisms are opposites.

Marxism required:

- Collective action against individual self-interest

- Violent expropriation of assets

- Central planning to replace market mechanisms

- People working hard without personal incentives

COA requires:

- Everyone acting in their self-interest

- Voluntary transactions at market prices

- Market mechanisms doing all the work

- Human nature exactly as it is

No one is forced. Shareholders sell voluntarily—often at premium prices. Employees take jobs they prefer. Customers buy products they like. Lenders make loans they consider safe.

There are losers, of course: conventional businesses that get outcompeted. But that's just market competition. The same thing that happens when any superior model displaces an inferior one. That's not injustice; it's how markets work.

And this doesn't require wealthy people to become worse off. As charitable ownership grows, investors shift toward bonds and other asset classes. Investment options change at the margin, but so does the world they live in. A future where global health and poverty are adequately funded isn't obviously worse for anyone.

This doesn't require convincing anyone to act against their interests. It requires philanthropists to wake up to the opportunity. After that, markets incorporate the preferences people already have.

The Asymmetric Bet

Even granting uncertainty, the expected value of testing COA is enormous.

Assign whatever probability you want. 50%? 30%? Even 10%?

Multiply by the upside: a mechanism that could eventually redirect a significant share of global profits to charity. Global corporate profits run into the trillions. Current charitable giving totals under $1.6 trillion. The scale of what's possible dwarfs current philanthropic capacity.

The downside is bounded. If you test COA by acquiring profitable businesses and it doesn't pan out, you still own profitable businesses. They still generate charitable distributions at baseline rates. Capital isn't lost, it just underperforms the thesis.

Heads, you change the world. Tails, you own profitable businesses generating ordinary returns for charity.

And the path from "early experiment" to "world changed" isn't mysterious. Early deployment generates evidence. If a portfolio of PFG businesses shows measurably better performance (higher margins, lower turnover, stronger retention), that evidence motivates other philanthropists and foundations to deploy. Their deployment generates more evidence. The theory proves itself through results, not arguments.

The problem isn't that philanthropists are ideologically opposed. It's that no one is running the experiment. The incentives for further deployment already exist—foundations want better returns, philanthropists want more impact. What's missing is the initial evidence that makes it obvious. Early movers create that evidence. The domino effect follows.

The bet isn't just that COA works. It's that proving it works—even at modest scale—unlocks capital that dwarfs the initial investment.

A note to skeptics: your skepticism of social enterprise is warranted. Businesses that pay premium wages, source high-cost ethical inputs, or sacrifice efficiency for values face real operational tradeoffs. That pattern-match makes sense.

But we live in an era of managerial capitalism. Owners don't manage businesses anymore. Ownership changes happen every day across global stock markets, and operations continue unaffected. If ownership transfers don't change how a business runs when shares move between funds, why would they change when shares move to a foundation?

This is not irrational exuberance about feel-good business. This is an unexploited mechanism: advantage through ownership identity.

That payoff profile of asymmetric upside and bounded downside, is exactly what serious philanthropic capital should pursue.

The Strange Thing

The strange thing isn't that COA might be true.

Given what we know about human preferences, market dynamics, margin leverage, and competitive displacement, COA being true is the default prediction. It's what the mechanism implies. For it to be false, human preferences would have to be inconsistent in ways that don't make sense.

The strange thing is that we haven't tested it at scale.

We have a thesis that could solve the funding constraint on effective charity. The intuition supports it. The evidence is directionally consistent. The theory predicts it should work broadly. Each of the four requirements is independently well-supported.

If COA is false, something unexpected is happening between documented preferences and market outcomes. Finding out what would be valuable in its own right.

If COA is true, we've found a mechanism to solve the funding problem for the world's most pressing issues.

Let's find out.

What I like most is that if you buy profitable companies, turn them into PFG's, and against all research and your arguments, there is a zero COA, you're still left with owning profitable companies. If that's the downside, it's somewhat absurd that there seems to be no philanthropist exploring this option to more efficiently multiply their giving.

Yeah, the downside would be the cost of running the program, which would be very small in relation to the value of the capital (which would be going to charity, so just subject to normal business risks).

If you see differences in post-acquisition performance, they can expand the fund and other philanthropists will have the incentive to copycat. If the thesis is generally proven, lenders will have the incentive to finance further acquisitions (leveraged buyouts); the sky, or most of the entire economy (other than perhaps startups where equity incentives might outweigh COA advantages), is the limit.

Truly absurd that this is not being explored.

I like this post and I think most of the arguments you make are good. But there's a big problem here which might make thus idea hard to pull off.

Most companies get successful and big largely because of driven founders and investors who push the business forward through greed and power-hungriness.

I think this your plan is worth a try, but it's easy to underrate how much greed and thirst for personal gain drive success in business. I wish altruism could be as strong a driver.

Greed and power can corrupt people along the way too. There's some evidence for this in the AI race. companies started as "non profits" but then were slowly corrupted and morphed into profit making companies for individuals.

I'm not saying it can't work, but I in think it takes really special kind of good person to drive and run a business that makes money truly for the good of others, AND don't get corrupted by greed and power over time if the company becomes successful. I'm not sure there are many of those people around.

Nick, I think you're imagining a different model than what I'm proposing. You're picturing a founder who needs to be driven by altruism instead of greed. That's not the idea.

The model is: a foundation buys an already-successful business from its existing owners and keeps the professional management in place. The managers keep getting paid salaries and bonuses. They keep running the business exactly as before. The only thing that changes is where the profits go after they're generated. This isn't about finding saintly founders. It's about acquisition. Private equity does this constantly. They buy businesses, keep management, extract profits. We're proposing the same thing, just with a charitable foundation as the equity holder instead of a PE fund.

You're right that greed drives startup founders. But startups are a tiny fraction of the economy. Most market share consists of mature companies run by professional managers who are already separated from ownership. They don't know or care whether their shares are held by Vanguard, Blackstone, or a foundation. They come to work, hit their targets, collect their bonus. That's the context where this operates.

This is precisely why this model is scalable. It doesn't require heroes. It just requires a foundation to buy out an existing business and keep the operations the same. In most businesses, management does not have much equity so the PFG business can offer the same compensation packages that a normal business would.

I'm broadly supportive of this type of initiative, and it seems like it's definitely worth a try (the downsides seem low compared to the upsides). However I suspect that, like most apparently good ideas, scrutiny will yield problems.

One issue I can think of: in this analysis, a lot of the competitive advantage for the company arises from the good reputation of the charitable foundation running it. However, running a large company competitively sometimes involves making tough, unpopular decisions, like laying off portions of your workforce. So I don't think your assumption that the charity-owned company can act exactly like a regular company holds up necessarily: doing so risks eliminating the reputational advantage that is needed for the competitive edge.

Yeah, there's the possibility of a double-standard. Essentially the PFG is reputationally penalized for competitive choices in ways their normal competitors are not.

It seems the short term solution to this is selecting contexts that aren't fraught with ethical issues.

And if you succeed in the short term, the long term solution would be a messaging campaign that tried to get at this irrational double-standard where competitive business choices are not popular.

I'd like to see someone trying a version of this, and European foundation owned businesses seem like a decent template. Do those businesses actually win due to charity ownership? If I were an investor or funding allocator, I'd like to see the pitch be much more concrete.

Edit: Brad addressed or clarified most of these points. Leaving it up as a reference, but most people can safely skip the below.

Kyle, appreciate the engagement. I think there's a core misread I should clear up: COA doesn't require anyone to pay more. That's the whole point. The thesis isn't "people will pay a premium for charity-owned." It's "at price parity, stakeholders prefer charity-owned, and that preference shows up in conversion, retention, and terms." You don't need customers to pay a charity tax. You need them to choose you over an equivalent competitor. The stated and revealed preference research suggests they will. So your concern about commodity and B2B customers actually supports my thesis. They won't pay more, and they don't have to. In fact, commodities might be the best for PFG if the business has the capital required, because it creates a differentiator where there are otherwise none. At equal price and quality, preference tips the balance. Even small advantages in win rates compound on thin margins. A business operating at 10% margin that improves by 5 percentage points doesn't improve profit by 5%. It increases by 50%.

On the acquisition mechanics: yes, you're buying profitable businesses at normal multiples. The thesis is that charitable ownership improves margins post-acquisition, not that you're getting a discount upfront. Debt service comes first, charitable distributions come from what remains. If COA improves margins even modestly, the spread over borrowing costs funds both repayment and distributions. Same as any leveraged acquisition, just with a different equity holder. And foundation-owned businesses actually show lower default rates in the data, so lending terms should be competitive or better. The "entire economy" scope follows from the mechanism. The preference operates on profit destination, not product category. And because the preference advantage doesn’t come with a clear operating disadvantage, we’d have to look for when a disadvantage might emerge. This could possibly be businesses like startups, where equity incentives for the key early players might outweigh such an advantage. But in most of the economy, ownership and management are separate. In the lower-middle market, where experimental acquisitions might feasibly take place, the kinds of acquisitions that keep operations in place but change ownership – continuity acquisitions- happen all the time

On the beachhead: agreed, this is what's needed. I'm working toward a fund structure to do instrumented acquisitions. The goal is generating real data, not just arguing from theory. Section 1.1 of the research compilation has more on the preference research if you want to dig in.

EDIT: Re AI timelines, one of the risks (certainly not the only one) is that it will cause wealth to be concentrated among the owners of capital. Having charities be the holders of that capital is likely a better outcome than a very small group who are accountable to no one.

If you're interested in the plausible margin effects, sector selection criteria, and financial projects, you can check out the research compilation that I linked to (Section 1 for stakeholder preference research, Section 4 on the effect of parity (no consumer sacrifice) on adoption, and Sections 9A and 9B on sector selection criteria and financial modeling, respectively).

And Claude helped organize and review the draft, but I wrote it.