This is a blog post I recently published talking about Paul Farmer, Partners in Health, maternal mortality in Sierra Leone, and my Giving What We Can pledge. The article is reproduced in full below:

Paul Farmer's Legacy

Source: Partners in Health

On February 21, 2022, Paul Farmer passed away at the age of 62.

During his life, Dr. Farmer co-founded Partners In Health (PIH), an organization that has transformed the landscape of global health by providing high-quality medical care to some of the world's most impoverished and marginalized communities. Through his work in Haiti, Rwanda, Peru, and beyond, Dr. Farmer demonstrated that it was not only possible but essential to deliver comprehensive health care in resource-poor settings.

He was a relentless advocate for the idea that health is a human right, not a luxury reserved for the fortunate few. He believed that every person, regardless of their circumstances, deserved access to quality medical care and the opportunity to live a healthy, dignified life.

Dr. Farmer's work transcended the traditional boundaries of medicine, encompassing the social, economic, and political factors that contribute to illness and suffering. He was a champion for social justice, tirelessly pushing for systemic change to address the root causes of health disparities.

At the time, I was completing my graduate studies in Epidemiology at the Colorado School of Public Health. At our weekly post-class beer, my classmates and I shared how Paul had inspired so many of us to pursue careers in public health and fight for health equity.

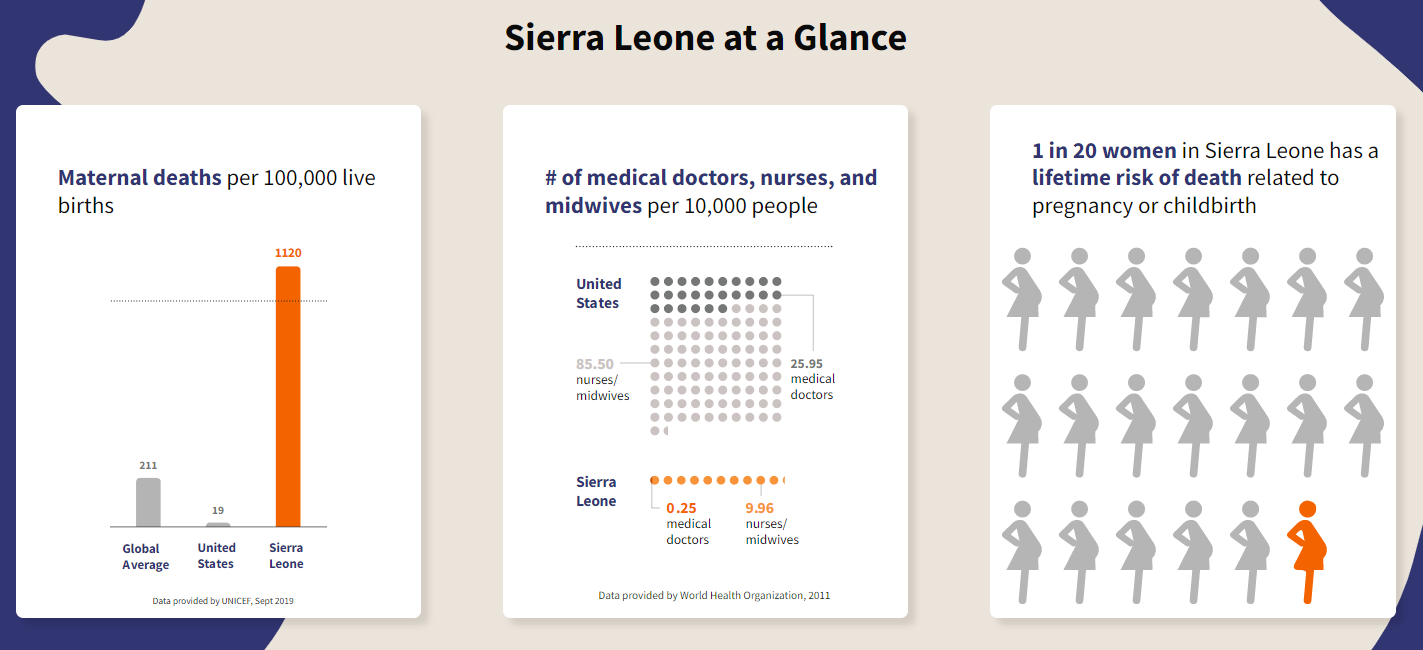

I first engaged with Paul Farmer and Partners in Health through John and Hank Green’s Youtube channel and community. In October of 2019, they announced that their family would be donating $6.5 million to PIH’s long term program to address maternal mortality in Sierra Leone, and called for support from their viewers. John’s words about the crisis struck me deeply, as he talked about the maternal mortality crisis:

10% of Sierra Leonean children do not live to see their fifth birthday, and three thousand women in Sierra Leone will die in pregnancy or childbirth this year. They will die of hemorrhaging that any well stocked hospital could easily address, they die because there is no electricity to keep the lights on during night time deliveries or to keep blood for transfusions refrigerated. Or they die because there is no running water which makes it difficult to sanitize tools or prevent infection. They die for want of medications or for want of surgical gloves. Or they will die because they need a c-section, and in Sierra Leone, a cesarean section is often a life threatening emergency. A woman delivering at home or at a local clinic will usually find that there is no ambulance to take her to the hospital, and so her best chance will be a long ride, dying, on the back of a motorbike. - John Green

source: Partners in Health

There are problems in this world that we need more resources, more scientific discoveries, more time to find the right solutions. This is not one of those problems. We know how to prevent the vast majority of maternal mortality, and do it efficiently and cheaply throughout the world. A century and a half ago, in 1873, every country that reliably tracked maternal mortality had a rate of between 600-1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births. As countries got richer, they invested money to solve this problem, and by 1980 there was a clear positive trend in maternal mortality rate across the world.

Since then, we have simply left sub-Saharan Africa behind.

Each region is a different color, with sub-Saharan Africa as light blue. Source: Gapminder

In 2017, the US had 720 total maternal deaths. Despite having a population 42x larger than that of Sierra Leone, 2,900 Sierra Leonean mothers died in 2017.

The bad news is that our world has done a horrible job at treating every person as equally valuable and worthy of the best opportunity to have a safe, healthy life. As Paul Farmer famously said, “the idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world.”

The good news is that we can change that. We have solved immense problems before. If you are feeling depressed by this information, I highly recommend reading 500 Million, But Not a Single One More (or watching the recent voiceover and animated video). This is a problem that we know how to solve; we just have to fight the urge to look away, and support the people who are fixing this gross inequity.

Paul Farmer’s death last year was the push I needed to take the Giving What We Can pledge, promising to donate 10% of my income to the most effective charities for the rest of my life. Half of my donations have gone to PIH’s work in Sierra Leone. I am not a wealthy person by the standards of my peer group, but I am in the top 1% wealthiest people in the world right now- and chances are good that if you are reading this post, you are too. These donations really matter to PIH’s work- they have since broken ground on the Maternal Center of Excellence, and John and Hank Green’s fundraising is on track to raise the $25 million to not only build the teaching hospital but staff it and supply it sustainably. They have also improved the maternal care available at Koidu Government Hospital, in partnership with the Ministry of Health. The facility now has:

24-hour electricity to support C-sections

a blood bank to respond to post-partum hemorrhages

a fully stocked pharmacy in labor and delivery

trainings for clinicians to improve their skills and provide better care to patients

These improvements have led to a 50% decrease in stillborn births at KGH, at the same time as they have seen a 52% increase in mothers served- and that is just the beginning. For more information on how this fundraising has been achieved and how this money is being spent, see this video or this page.

One year later into my giving pledge, it is one of the best decisions I have ever made. Just as those before us were part of humanity’s combined effort to banish disease from smallpox permanently from the world, we can be a part of the generation that ends the infant and maternal mortality crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. I will leave you again with the words of Dr Farmer:

The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world

If you are interested in the idea of a pledge, but don’t know if you can commit to 10% of your income over the rest of your life, I would encourage you to look into the Giving What We Can Trial Pledge, where you pick the amount and duration that you feel comfortable starting with. Thank you to Simon Bazelon, Sam Harris, Luke Freeman, Grace Adams, and the Giving What We Can team, and the EA community for helping to normalize talking about effective giving. You can learn more about maternal mortality, Partners in Health, and the Giving What We Can pledge here:

Really enjoyed reading this - thanks for posting!

Thanks!

Here's an update video on the Maternal Center of Excellence