I've spent quite a bit of time over the last few years trying to answer two questions:

- Will World War III break out this century?

- If it does, could it be so devastating that it causes an existential catastrophe, threatening humanity’s long-term future?

It's been fun.

Last week I published an in-depth problem profile for 80,000 Hours that sums up what I’ve found so far: that World War III is perhaps surprisingly likely and we can’t rule out the possibility of a catastrophic escalation. It also discusses some ideas for how you might be able to help solve this problem.

This post includes the top-line summary of the profile. Following that, I draw out the highlights that seem particularly relevant for the EA community.

Profile Summary

Economic growth and technological progress have bolstered the arsenals of the world’s most powerful countries. That means the next war between them could be far worse than World War II, the deadliest conflict humanity has yet experienced.

Could such a war actually occur? We can’t rule out the possibility. Technical accidents or diplomatic misunderstandings could spark a conflict that quickly escalates. Or international tension could cause leaders to decide they’re better off fighting than negotiating.

It seems hard to make progress on this problem. It’s also less neglected than some of the problems that we think are most pressing. There are certain issues, like making nuclear weapons or military artificial intelligence systems safer, which seem promising — although it may be more impactful to work on reducing risks from AI, bioweapons or nuclear weapons directly. You might also be able to reduce the chances of misunderstandings and miscalculations by developing expertise in one of the most important bilateral relationships (such as that between the United States and China).

Finally, by making conflict less likely, reducing competitive pressures on the development of dangerous technology, and improving international cooperation, you might be helping to reduce other risks, like the chance of future pandemics.

Overall view

Recommended

Working on this issue seems to be among the best ways of improving the long-term future we know of, but all else equal, we think it’s less pressing than our highest priority areas (primarily because it seems less neglected and harder to solve).

Importance:

There's a significant chance that a new great power war occurs this century.

Although the world's most powerful countries haven't fought directly since World War II, war has been a constant throughout human history. There have been numerous close calls, and several issues could cause diplomatic disputes in the years to come.

These considerations, along with forecasts and statistical models, lead me to think there's about a one-in-three chance that a new great power war breaks out in roughly the next 30 years.

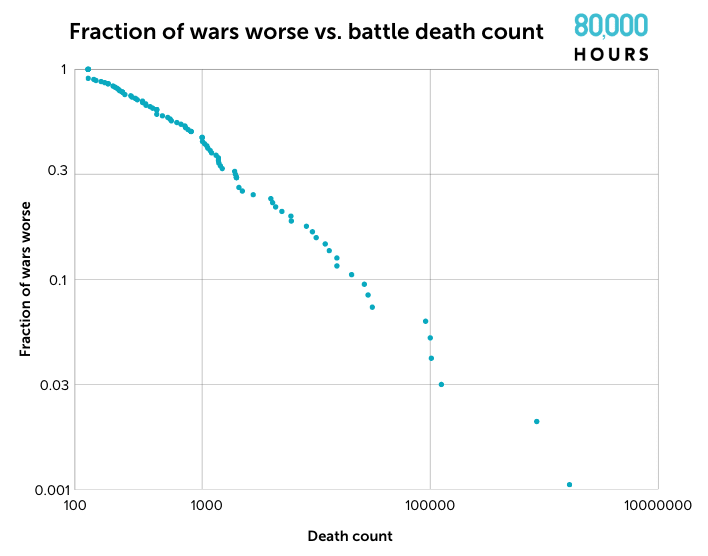

Few wars cause more than a million casualties and the next great power war would probably be smaller than that. However, there's some chance it could escalate massively. Today the great powers have much larger economies, more powerful weapons, and bigger military budgets than they did in the past. An all-out war could kill far more people than even World War II, the worst war we've yet experienced.

Could it become an existentially threatening war — one that could cause human extinction or significantly damage the prospects of the long-term future? It's very difficult to say. But my best current guess is that the chance of an existential catastrophe due to war in the next century is somewhere between 0.05% and 2%.

Neglectedness:

War is a lot less neglected than some of our other top problems. There are thousands of people in governments, think tanks, and universities already working on this problem. But some solutions or approaches remain neglected. One particularly promising approach is to develop expertise at the intersection of international conflict and another of our top problems. Experts who understand both geopolitical dynamics and risks from advanced artificial intelligence, for example, are sorely needed.

Solvability:

Reducing the risk of great power war seems very difficult. But there are specific technical problems that can be solved to make weapons systems safer or less likely to trigger catastrophic outcomes. And in the best case, working on this problem can have a leverage effect, making the development of several dangerous technologies safer by improving international cooperation and making them less likely to be deployed in war.

At the end of this profile, I suggest five issues which I’d be particularly excited to see people work on. These are:

- Developing expertise in the riskiest bilateral relationships

- Learning how to manage international crises quickly and effectively and ensuring the systems to do so are properly maintained

- Doing research to improve particularly important foreign policies, like strategies for sanctions and deterrence

- Improving how nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction are governed at the international level

- Improving how such weapons are controlled at the national level

Highlights for an EA audience

The full profile is a major update to 80k’s content on great power conflict. It’s also a kind of update to my Founders Pledge report and previous Forum posts on conflict as a risk factor, the likelihood of World War III, and the potential for catastrophic wars (co-authored with Rani Martin).

Some highlights and updates that seem particularly relevant to an EA audience are:

- Revised forecasts of the likelihood of major conflict this century. I haven’t updated majorly since “How Likely is WWIII?”. Before 2050, I think there’s a 30-40% chance we see direct conflict between great power countries and a 10% chance we see a war we could reasonably call World War III.

- I’ve added a lot of detail in the profile about how a war could happen through rapid escalation following a technical or human error or as a result of a bargaining failure (adopting the useful framework from Prof. Chris Blattman’s book Why We Fight)

- Some new thinking about how likely war is to cause an existential catastrophe. I make rough estimates of the likelihood of both an extinction war and a civilizational collapse or trajectory-bending war. The latter is much more likely but its effects are much more uncertain. On the whole I estimate the amount of x-risk war poses this century to be between 0.05% and 2% (thanks to Benjamin Hilton for his help with this section).

- I think I overestimated the risk of an extinction-level war in “How Likely is WWIII?”, but this is partly offset by accounting for other ways war could cause an existential catastrophe

- I’m more confident that enormous wars are possible and even worryingly likely. Rani Martin and I had previously speculated that enormous wars much larger than WWII are even less likely than statistical models imply. I now don’t weigh those considerations very highly.

- Instead, I think the evidence from statistical analyses, theoretical models, and forecasts all suggest that a modern global war could indeed escalate to kill hundreds of millions or billions of people.

- I raise the tricky issue of subtle trajectory changes. Any major great power war seems likely to have a bunch of important, long-lasting effects even if it doesn’t threaten us with extinction. They shift global power balances, and in their aftermath borders can be redrawn, institutions created or destroyed, and technological development pathways altered.

- I’m still very unsure how to think about the expected net effect of these factors and mostly skirt the issue. But I wanted to raise it as a potential useful departure point for future work.

- I think a bit more about how to prioritise work on this topic vs. 80,000 Hours’ other priorities. Ultimately I do think other existential risks seem potentially more important and less neglected than global conflict. But I do think this is still a pathway some people in the EA community should pursue, for a few reasons.

- There may be relatively low-hanging fruit to pick within the area that a scope-sensitive, impact-focused, altruistic person can work on.

- Personal fit factors could very plausibly overwhelm other factors.

- I think developing expertise at the intersection of geopolitics/diplomacy and some other important issue (like AI risk or US-China relations) seems highly and robustly valuable.

- I suggest some places where people could work and issues that they could focus on. Those issues are:

- The riskiest bilateral relationships. Become an expert on US-China, US-Russia, or China-India relations.

- Crisis management. Think about how to avoid and de-escalate technical accidents, international misperceptions, or border conflicts.

- Scrutinising important foreign policies, like US export control policy

- How to govern weapons of mass destruction and emerging weapons technologies at the international level

- How to control and keep such weapons safe at the national level

I tried to load the profile with concrete examples and anecdotes, including the stories of the most devastating conflicts and near-misses throughout history.

Naturally, the Paraguayan War of 1864-70 warrants a paragraph of its own (real ones know).

I’m excited to have this published and hope to see more people work in this area!

In the 80k article, I noticed the claim that the Ukraine war had killed 'hundreds of thousands'.

Looking over various estimates collected on Wikipedia, as far as I can tell, it is around ~100,000. Is there a reason to believe it is much higher than this?

I felt uncertain whether to write this comment as it feels very pedantic, but I think making sure we get small details right is important to be credible about the speculative risk estimates that can't be easily looked up.

Thanks for catching that, you're absolutely right. That should either read about 100,000 deaths or hundreds of thousands of casualties. I'll get that fixed.

Thank you Stephen for your long engagement with this topic, because I do think it is a very real risk that Effective Altruists should pay more attention to.

In addition to the actions you proposed, I also wanted to suggest there might be promising actions in reducing conflicts of interests that incentivise conflict and escalate tensions. The high amounts of political lobbying, sponsoring of think tanks and universities, by weapons companies creates perverse inventives.

I have been very impressed by the work of the Quincy Institute to bring attention to this issue, and to explore diplomatic options as alternatives to conflict. I would love to see 80000 Hours promote them on their job board or interviewed.

I've written to my local MPs about banning contributions from weapons makers (Lockheed Martin, Boeing etc...) to the Australian Gov't military think tank ASPI. Here in Australia the recent AUKUS security pact has seen an enormous increase in planned military spending and sparked some discussion on the forum. I am trying to raise this as an issue/cause area to explore amongst Aussie EAs.

Thanks for this! I agree interventions in this direction would be worth looking into more, though I'd also say that tractability remains a major concern. I'm also just really uncertain about the long-term effects.

I think the Quincy Institute is interesting but want to note that it's also very controversial. Seems like they can be inflammatory and dogmatic about restraint policies. From an outside perspective I found it hard to evaluate the sign of their impact, much less its magnitude. I don't think I'd recommend 80K put them on the job board right now.

I largely agree with your assessment that Quincy is controversial and dogmatic about restraint/ non-intervention.

That being said, they are a valuable source of disagreement in the wider foreign policy community, and doing something very neglected (researching & advocating for restraint/non-intervention).

I know Quincy staff disagree with each other, coming from libertarian, leftist, realist perspectives. So it is troubling that Cirincione departed because that difference in perspective is needed. Although I do suspect Parsi is describing things accurately when he says Cirincione left because he wanted the Institute to adopt his position in the Russian-initiated war on Ukraine.

Quincy are exploring a controversial analysis in this current conflict in Russia-Ukraine, to identify if Russia's invasion could have been avoided in the 1st place (e.g. by bringing Russia into NATO way back when they were wanting to join), and advocating Ukraine and Russia compromise to reduce casualties (to be fair, it's reported the White House has also urged Ukraine to make compromises at times). Whilst controversial, I do think this is worthwhile, and I myself might disagree (and I believe they all disagree amongst themselves), I want to see this research/advocacy explored and debated. I had been nervous when the invasion started that Quincy's work could dip into Kremlin-apologetics, but they have seemed to steer away from that, and have nuanced perspectives.

Their work on the Iran Nuclear Deal, the conflict in Yemen, is far less controversial, and promising.

I find value in them being a counterbalance to the more hawkish think tanks which are much better resourced.

On the 80K job board, you have a few institutions (well respected and worthwhile no doubt) like CSIS & RAND, which are more interventionist and/or funded by arms manufacturers (even RAND is indirectly funded by the grants it receives from AEI), so I do worry that there is a systemic bias for interventionist views.

I hope people don't write-off Quincy's work or other anti-interventionist/restraint-focused work entirely, but certainly agree, take it with a grain of salt. I certainly do.

Thanks for this post. Reducing risks of great power war is important, but also consider reducing risks from great power war. In particular working on how non-combatant nations can ensure their societies survive the potentially catastrophic ensuing effects on trade/food/fuel etc. Disadvantages of this approach are that it does not prevent the massive global harms in the first place, advantages are that building resilience of eg relatively self-sufficient island refuges may also reduce existential risk from other causes (bio-threats, nuclear war/winter, catastrophic solar storm, etc).

One approach is our ongoing project the Aotearoa New Zealand Catastrophe Resilience Project.

Also, 100,000 deaths sounds about right for the current conflict in Ukraine, given that recent excess mortality analysis puts Russian deaths at about 50,000.