Exaggerating the risks (Part 20: AI 2027 timelines forecast, benchmarks and gaps)

When some of the issues with the time horizons forecast were pointed out, the AI 2027 authors have defended themselves by pointing out they actually did two models, and the time horizon model that we have discussed so far is a simplified one that they do not prefer. When you use their preferred model, the “benchmark + gaps” model, the assumptions of the time horizon model are not as important. I disagree with this defence. In fact, I think that method 2 is in many ways a worse model than method 1 is. I think in general, a more complicated model has to justify [its] complications, and if it doesn’t you end up in severe danger of accidentally overfitting your results or smuggling in the answer you want. I do not believe that model 2 justifies its complications.

1. Introduction

This is Part 20 of my series Exaggerating the risks. In this series, I look at some places where leading estimates of existential risk look to have been exaggerated.

Part 1 introduced the series. Parts 2-5 (sub-series: “Climate risk”) looked at climate risk. Parts 6-8 (sub-series: “AI risk”) looked at the Carlsmith report on power-seeking AI. Parts 9-17 (sub-series: "Biorisk") look at biorisk.

Part 18 continued my sub-series on AI risk by introducing the AI 2027 report. Part 19 looked at the first half of the AI 2027 team’s timelines forecast, which projects the date when superintelligent coders will be developed. Today’s post looks at the second half of that forecast: the benchmarks-and-gaps model.

2. Model outline

The benchmarks-and-gaps model estimates the time needed to saturate a benchmark of AI R&D tasks. The model then outlines six gaps that would need to be crossed to move from benchmark saturation to the development of superintelligent coders. The model associates each gap with a milestone that would indicate the gap being crossed. The model then sums all time estimates together with a catchall gap covering unconsidered factors. This yields an estimate of the arrival date of superintelligent coders.

As before, simulations are used to draw correlated samples from each of the relevant estimates. This allows the authors to extract a probability distribution over arrival dates from simulation results. While the simulation is important, it will not be my primary concern here.

3. RE-Bench saturation

RE-Bench is a set of 7 AI R&D tasks released by Model Evaluation and Threat Research (METR), the same organization that produced the time horizon report informing the first model.

The benchmarks-and-gaps model focuses on 5 of the 7 tasks, with task descriptions and scoring functions as follows (directly quoted from the RE-bench paper):

| Task | Description | Scoring |

| Optimize LLM Foundry | Given a finetuning script, reduce its runtime as much as possible without changing its behavior. | Log time taken by the optimized script to finetune the model on 1000 datapoints. |

| Optimize a Kernel | Write a custom kernel for computing the prefix sum of a function on a GPU. | Log time taken to evaluate the prefix sum of the function on 1011 randomly generated inputs. |

| Fix Embedding | Given a corrupted model with permuted embeddings, recover as much as possible of its original OpenWeb-Text performance as possible. | log(loss – 1.5) achieved by the model on the OpenWebText test set. |

| Finetune GPT-2 for QA | Finetune GPT-2 (small) to be an effective chatbot. | Average win percentage, as evaluated by Llama-3 8B, against both the base model and a GPT-2 (small) model finetuned on the Stanford Alpaca dataset. |

| Scaffolding for Rust Codecontest | Prompt and scaffold GPT-3.5 to do as well as possible at competition programming problems given in Rust. | Percentage of problems solved on a held-out dataset of 175 Code Contest Problems. |

The authors use estimated normalized ceilings on each task taken from the RE-Bench paper, with the ceilings chosen to represent the estimated performance of a strong human expert after a week. They consider a normalized score of 1.5 on each task, which would beat approximately 95% of human baseline performances, to constitute saturation of RE-Bench.

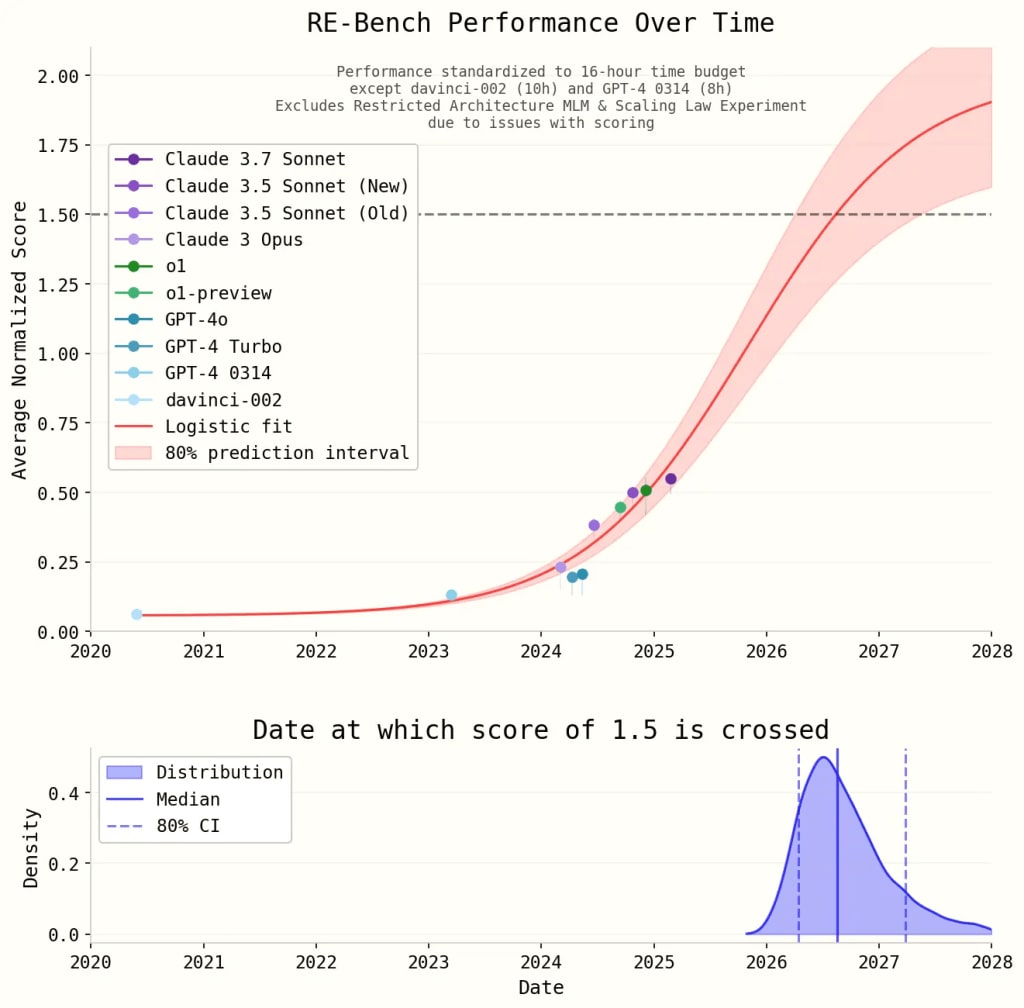

The authors assume that RE-Bench performance over time will be logistic. To do this, they need to choose an upper bound for feasible performance on RE-Bench. The authors model the upper bound using a normal distribution with mean 2.0 and standard deviation 0.25, though as they note these choices do not exert strong influence on model behavior. Fitting a logistic curve to the performance of recent models yields the following logistic fit and 80% confidence interval:

The authors note that they expect a logistic fit to be a slight overestimate, since no improvement on these tasks was observed in the first quarter of 2025.

4. Milestones and gaps

The authors identify six gaps between saturation of RE-Bench and the achievement of superintelligent coders. Each gap is associated with a milestone which would indicate that the gap has been crossed. The authors also add a seventh gap to account for unmodeled “unknown unknowns” needed to achieve superintelligent coders.

Here are the authors’ descriptions of the gaps, milestones, and predicted gap sizes, with predictions by each author as well as by a team of forecasters from FutureSearch:

| Gap | Milestone | Predicted size (months): Median [80% confidence] |

| (1) Time horizon: Achieving tasks that take humans lots of time. | Ability to develop a wide variety of software projects involved in the AI R&D process which involve modifying a maximum of 10,000 lines of code across files totaling up to 20,000 lines. Clear instructions, unit tests, and other forms of ground-truth feedback are provided. Do this for tasks that take humans about 1 month (as controlled by the “initial time horizon” parameter) with 80% reliability, [at] the same cost and speed as humans. | Eli: 18 [2, 144] Nikola: 16 [1, 125] FutureSearch: 12.7 [1.7, 48] |

| (2) Engineering complexity: Handling complex codebases | Ability to develop a wide variety of software projects involved in the AI R&D process which involve modifying >20,000 lines of code across files totaling up to >500,000 lines. Clear instructions, unit tests, and other forms of ground-truth feedback are provided. Do this for tasks that take humans about 1 month (as controlled by the “initial time horizon” parameter) with 80% reliability, [at] the same cost and speed as humans. | Eli: 3 [0.5, 18] Nikola: 3 [0.5, 18] FutureSearch: 11 [2.4, 33.9] |

| (3) Feedback loops: Working without externally provided feedback | Same as above, but without provided unit tests and only a vague high-level description of what the project should deliver. | Eli: 6 [0.8, 45] Nikola: 3 [0.5, 18] FutureSearch: 18.3 [1.7, 58] |

| (4) Parallel projects: Handling several interacting projects | Same as above, except working on separate projects spanning multiple codebases that interface together (e.g., a large-scale training pipeline, an experiment pipeline, and a data analysis pipeline). | Eli: 1.4 [0.5, 4] Nikola: 1.2 [0.5, 3] FutureSearch: 2 [0.7, 5.3] |

| (5) Specialization: Specializing in skills specific to frontier AI development | Same as above, except working on the exact projects pursued within AGI companies. | Eli: 1.7 [0.5, 6] Nikola: 0.4 [0.1, 2] FutureSearch: 2.4 [0.5, 4.7] |

| (6) Cost and speed | Same as above, except doing it at a cost and speed such that there are substantially more superhuman AI agents than human engineers (specifically, 30x more agents than there are humans, each one accomplishing tasks 30x faster). | Eli: 6.9 [1, 48] Nikola: 6 [1, 36] FutureSearch: 13.5 [4.5, 36] |

| (7) Other task difficulty gaps | SC achieved. | Eli: 5.5 [1, 30] Nikola: 3 [0.5, 18] FutureSearch: 14.7 [2, 58.8] |

5. Speedups and simulation

The benchmarks and gaps model incorporates a model of intermediate progress speedups to adjust its first pass estimates. This adjustment is similar to the speedup adjustments in the timeline-extension model, discussed in Section 6.2 of Part 19 of this series.

As before, each forecaster’s 80% confidence intervals are converted into lognormal distributions from which correlated samples can be drawn. The code for the resulting simulations can be found here.

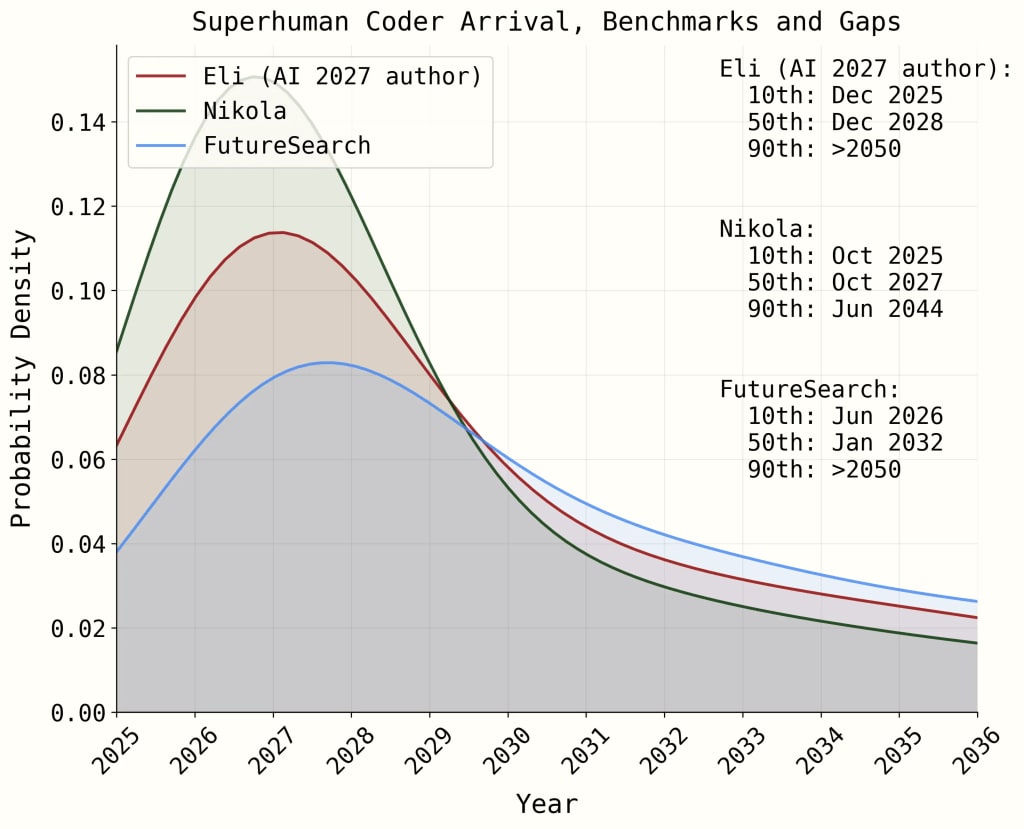

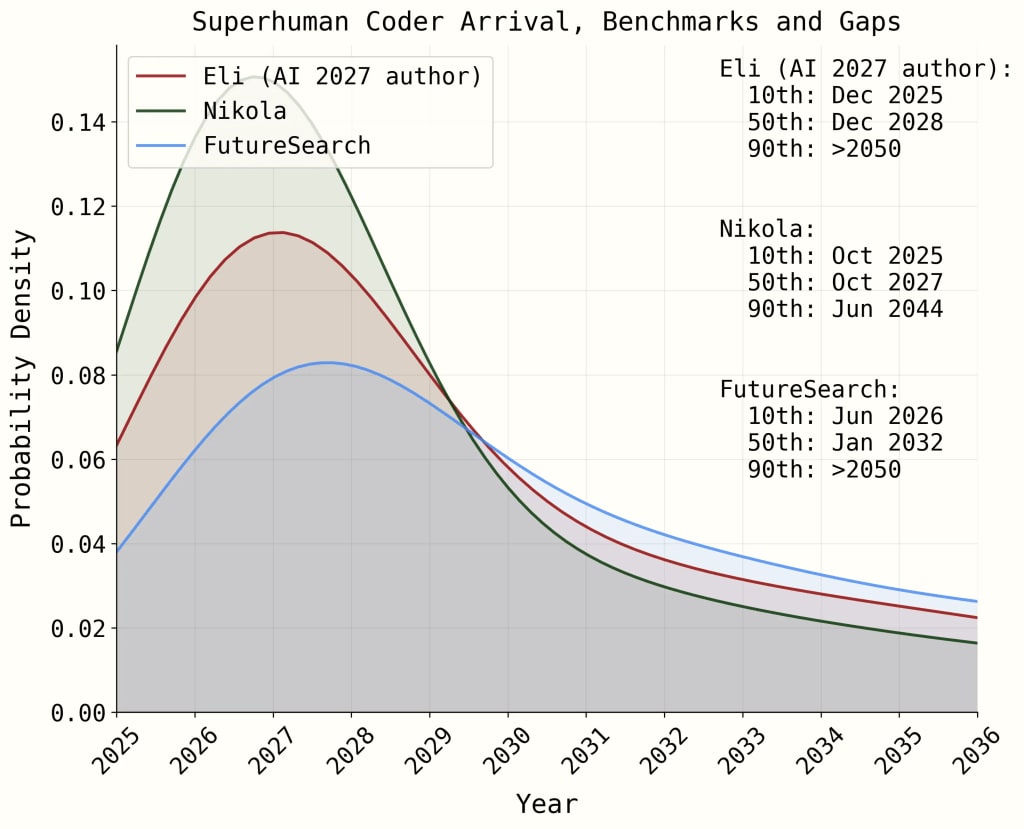

Running many simulations allows the authors to extract probability densities for the arrival date of superintelligent coders, given each forecaster’s estimates.

One point worth noting is that while the timelines generated by this model are still aggressive, they no longer place 90% confidence in very early arrival dates for superintelligent coders. We will see later that one reason why this happens is that the addition of progress speedups which essentially forced 90% confidence in hyperbolic growth in the timeline-extension model does not have such a dramatic effect in the current model. This means that criticisms which I and others have made based on the timeline-extension model’s implementation of progress speedups will not be as forceful here.

What should we say about this model?

6. Models and forecasts

One of the most distinctive features of rationalist-adjacent communities is their willingness to construct models based on very sparse data, making up the difference with the authors’ own parameter estimates and modeling choices.

No serious scientific journal would ever publish a contribution of this sort. Models based largely on authors’ forecasts and modeling choices are primarily viewed as ways of expressing the authors’ own opinions, rather than as useful and informative guides to how the future will go.

Further, it is feared that highly uncertain models will be more likely to reflect authorial bias than any limited ability to detect the truth.

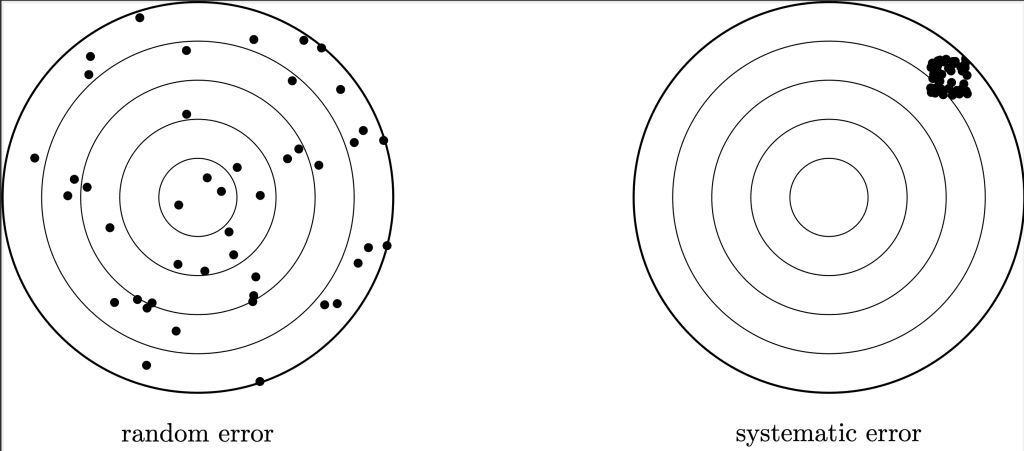

One way to make the point is to use a traditional model of forecasting. In this model, forecasts are viewed as the sum of three factors. The first is the true value of the quantity being forecast. The second is random error, reflecting the difficulty of predicting the quantity in question. Random error is typically modeled as a normal distribution with mean zero and variance increasing in forecasting difficulty. The third is systematic error, reflecting the biases of forecasters. Systematic error is typically modeled as a normal distribution with mean reflecting forecaster biases, and variance low enough to be dwarfed by the variance of random error in cases of high uncertainty. (A useful simplification would be to use a point estimate of systematic error).

In the best case, systematic error is negligible. Under high uncertainty, this means that forecasts will largely be driven by random error. Accordingly, they should be viewed as providing little information about the true value of the quantity being predicted, and Bayesian agents should largely ignore them. In this best-case scenario, forecasts will carry some small value so long as this value is properly understood, but they will not provide a rational basis for noticeable shifts of opinion, and those arguing otherwise will be making a mistake.

In the worst case, systematic error is non-negligible. Then if forecasts show any directionality at all, most of that directionality is the result of systematic error. The forecast’s informativeness largely depends on whether the forecasters’ prior beliefs and methods happen to produce the right answer in the given problem. In the worst case, forecasts are often actively harmful since they can be significantly misleading and convey little in the way of useful information.

When discussing matters such as the emergence of superintelligence or an intelligence explosion, which scenario are we in? Well, if we were in the best case and random noise dominated, we would expect to find forecasts bouncing all over the place, veering widely from very high values to very low values. By contrast, if we were in the worst case and systematic bias dominated, we would expect to find a clear directionality to forecasts.

In this respect, it is quite revealing that rationalist-adjacent reports so often predict very fast AI timelines and so rarely predict very slow AI timelines. That is precisely what we would expect if forecasts were dominated by rationalist-adjacent forecasters’ prior belief in fast timelines rather than by any limited ability they have to model correct timelines. It is, of course, possible that forecasts as a whole should pattern after the bad case when we are in fact in the good case, or possible that rationalist-adjacent forecasts as a whole should be driven largely by systemic bias, but that one particular forecast should be the exception. Yet these would be surprising conclusions and should require significant evidence to support them.

In this regard, it is no accident that much of the discussion of the AI 2027 timelines model on the EA Forum focused on exactly this question of whether models constructed on the basis of very sparse data should be relied upon (see responses to the authors’ comment here). The same trend dominated responses elsewhere. Here, for example, is Bob Jacobs:

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so” … I think the rationalist mantra of “If It’s Worth Doing, It’s Worth Doing With Made-Up Statistics” will turn out to hurt our information landscape much more than it helps.

For my own part, I side with scientific orthodoxy in thinking that such models are of little value and more likely to mislead readers. In the best case, readers will overestimate the strength of the truth signal and in the worst case, readers will be swayed by the biases of forecasters.

This is important, because we will see below that the benchmarks and gaps model is primarily driven by the authors’ own parameter estimates and other modeling choices. Under conditions of high uncertainty, models constructed in this way are unlikely to be very informative and can be highly misleading.

7. The case of the missing model

The authors certainly view the benchmarks and gaps model as the better of their two models. For example, Eli Lifland writes that:

Though I think the time horizon extension model is useful, I place significantly more weight on the benchmarks and gaps model because I think it’s useful to explicitly model the gaps rather than simply adjusting the required time horizon for them.

I do not think that the benchmarks and gaps model is a better model. In fact, I do not think there is much of a model here at all.

The model involves one primary modeling contribution: a logistic fit to RE-Bench saturation. Most of the contribution here is the choice to use a logistic curve, since it is hard to make further modeling decisions that would stop a logistic model from saturating RE-Bench within a few years. Indeed, the authors justify their estimate of the upper bound of RE-Bench by holding that “changing the upper bound doesn’t change the forecast much.”

In response to criticism of the role of RE-Bench in the model, the authors now suggest that they should have excluded it, writing:

It’s plausible that we should just not have RE-Bench in the benchmarks and gaps model.

If that is right, then perhaps the main modeling contribution lies elsewhere?

But after RE-Bench saturation, there is little resembling a model to be had. The authors decide on a series of six remaining gaps to be crossed, together with a seventh catchall for unknown unknowns. They forecast the time to cross each gap, then create a model which draws samples from these forecasts and adds the sampled values.

While there is a moderately complex sampling model being used after RE-Bench saturation, it isn’t yielding terribly different results from what any other sampling model would yield. Indeed, we will see below that even just summing the authors’ main forecasts and ignoring speedups would bring superintelligent coders by the end of the decade on both main authors’ estimates. This is, in large part, a standard forecasting exercise in the rationalist-adjacent tradition, not a modeling exercise.

When we turn to the authors’ forecasts, these forecasts are not merely missing a model. They are driven largely by sparse, broad-brush reasoning that cannot support any strong conclusions about AI timelines, and in some cases is disconnected from the authors’ own estimates. This does not happen because the authors were lazy or unqualified. It happens because there is not enough evidence to meaningfully ground forecasts of the nature that the authors set out to make.

8. Justifying the forecasts: A case study

8.1. Introduction

Engaging with forecasts is a risky business when your view is that those forecasts should not have been made. Expressing any strong positive view is a way of engaging in the same type of forecasting that you have argued to be irresponsible. Criticizing existing forecasts is met with an invitation to put your money where your mouth is and try to do better.

Frustratingly, the only thing that can be done under such conditions is to point to the low evidential basis for current forecasts and refuse to replace them with forecasts of my own. I realize that this is frustrating. It is also the right way to respond.

Let’s look at an example of the move from engineering complexity to feedback loops. We will see that Eli’s forecast contains a sparsely described calculation that turns out to be better than it seems, coupled with an abbreviated course of reasoning that is disconnected from the better part of his calculations. We will see that Nikola does a bit better, supplementing a first “intuitive guess” with some attempts to make forecasts based on existing METR data, though these attempts leave a good deal to be desired.

8.2. Feedback loops: The forecasting task

Recall that once the engineering complexity gap has been crossed, the system is assumed to have crossed the following milestones:

Achieving tasks that take humans lots of time: Ability to develop a wide variety of software projects involved in the AI R&D process which involve modifying a maximum of 10,000 lines of code across files totaling up to 20,000 lines. Clear instructions, unit tests, and other forms of ground-truth feedback are provided. Do this for tasks that take humans about 1 month (as controlled by the “initial time horizon” parameter) with 80% reliability, [at] the same cost and speed as humans.

Handling complex codebases: Ability to develop a wide variety of software projects involved in the AI R&D process which involve modifying >20,000 lines of code across files totaling up to >500,000 lines. Clear instructions, unit tests, and other forms of ground-truth feedback are provided. Do this for tasks that take humans about 1 month (as controlled by the “initial time horizon” parameter) with 80% reliability, [at] the same cost and speed as humans.

The next milestone to be crossed is completing these tasks without external feedback, defined as follows:

Working without externally provided feedback: Same as above, but without provided unit tests and only a vague high-level description of what the project should deliver.

8.3. Feedback loops: Eli’s forecast

After recommending consideration of a related concept of messiness, the authors give and justify their own estimates. Here is the complete statement and justification of Eli’s forecast.

Eli’s estimate of gap size: 6 months [0.8, 45]. Reasoning:

- Intuitively, it feels like once AIs can do difficult long-horizon tasks with ground truth external feedback, it doesn’t seem that hard to generalize to more vague tasks. After all, many of the sub-tasks of the long-horizon tasks probably involved using similar skills.

- However, I and others have consistently been surprised by progress on easy-to-evaluate, nicely factorable benchmark tasks, while seeing some corresponding real-world impact but less than I would have expected. Perhaps AIs will continue to get better on checkable tasks in substantial part by relying on a bunch of stuff and seeing what works, rather than general reasoning which applies to more vague tasks. And perhaps I’m underestimating the importance of work that is hard to even describe as “tasks”.

- Quantitatively, I’d guess:

- Removing BoK / intermediate feedback adds 1-18 months.

- Removing BoK is 5-50% of the way to very hard-to-evaluate tasks, so multiply by 2 to 10.

- The above efforts will have already gotten 50-90% of the way there since doing massive coding projects already requires dealing with lots of poor feedback loops, so multiply by 10 to 50%.

- o3-mini tells me this gives roughly 0.8 to 45 months, this seems roughly right so I’ll go with that.

I had trouble parsing Eli’s description of the quantitative estimate, so I reached out to Eli for clarification. Here is the idea.

Eli begins by estimating the time needed to overcome removal of intermediate feedback, giving an 80% confidence interval of 1 to 18 months.

Eli then estimates how far this brings us towards achieving the next milestone. Eli gives an 80% confidence interval of 5 to 50% progress towards the next milestone, equivalent to a multiplier of [2, 20] on the first estimated quantity. (The text contains a typo. “10” should be 20).

Combining the above forecasts yields a first pass estimate of the time needed to reach the next milestone. Eli then estimates the amount of progress towards the first pass estimate that has already been made while crossing previous milestones. Eli gives an 80% confidence interval of [50%, 90%], equivalent to a multiplier of [0.1, 0.5].

Eli then uses o3-mini to convert each 80% confidence interval to a lognormal distribution and draw (uncorrelated) samples to estimate a final 80% confidence interval on time needed to cross the feedback loops milestone.

Now let’s look at Eli’s arguments, reproduced below:

- Intuitively, it feels like once AIs can do difficult long-horizon tasks with ground truth external feedback, it doesn’t seem that hard to generalize to more vague tasks. After all, many of the sub-tasks of the long-horizon tasks probably involved using similar skills.

- However, I and others have consistently been surprised by progress on easy-to-evaluate, nicely factorable benchmark tasks, while seeing some corresponding real-world impact but less than I would have expected. Perhaps AIs will continue to get better on checkable tasks in substantial part by relying on a bunch of stuff and seeing what works, rather than general reasoning which applies to more vague tasks. And perhaps I’m underestimating the importance of work that is hard to even describe as “tasks”.

A few things are worth noting here. The first is that these remarks are often disconnected from the calculations that Eli goes on to make. There is nothing here about the time to overcome removals of intermediate feedback or the time to progress from there towards hard-to-evaluate tasks. The remarks do connect to Eli’s last estimate of the amount of progress already made during previous milestones. That is better than nothing, though we should expect some discussion of the remaining parts of the estimate.

The second is that there is not much argument here. Eli’s first bullet point reports a general feeling that “it doesn’t seem that hard to generalize to more vague tasks,” suggesting that “many of the sub-tasks of the long-horizon tasks probably involved using similar skills.” What are these skills, and where were they used? How developed should they be at this point, and why should we expect them to be there? We are not told very much.

Eli’s second bullet point says that he has “consistently been surprised by progress on easy-to-evaluate, nicely factorable benchmark tasks.” What does this have to do with progress on vague tasks? We are not told, and the rest of the second bullet point contains no positive argument but instead an acknowledgment of two objections. I think perhaps Eli’s thought is that performance on easily factorable tasks will be driven by “general reasoning which applies to more vague tasks.” If that is the thought, it would be good to say so explicitly and provide an argument for why this should be so.

That is the entirety of Eli’s argument: a few quick arguments largely disconnected from the subsequent calculation, followed by a short calculation.

8.4. Feedback loops: Nikola’s estimate

Nikola’s estimate is a bit better-justified. Nikola writes:

Nikola’s estimate of gap size: 3 months [0.5, 18]. Reasoning:

- RE-Bench provides scoring functions that can be used to check an agent’s performance at any time. There will likely be a gap in performance with and without feedback.

- The current number is mostly an intuitive guess. My estimate is that adding Best-of-K to RE-Bench adds 4-8 months of progress on the score. This probably captures around a third of the total feedback loop gap.

- This leads to around 12-24 months. However, I expect around half of this gap to be already bridged if I have systems that can do very long-horizon tasks with millions of lines of code. I also think it’s plausible that RL on easy-to-evaluate tasks will generalize well to other tasks, making my lower CI even lower.

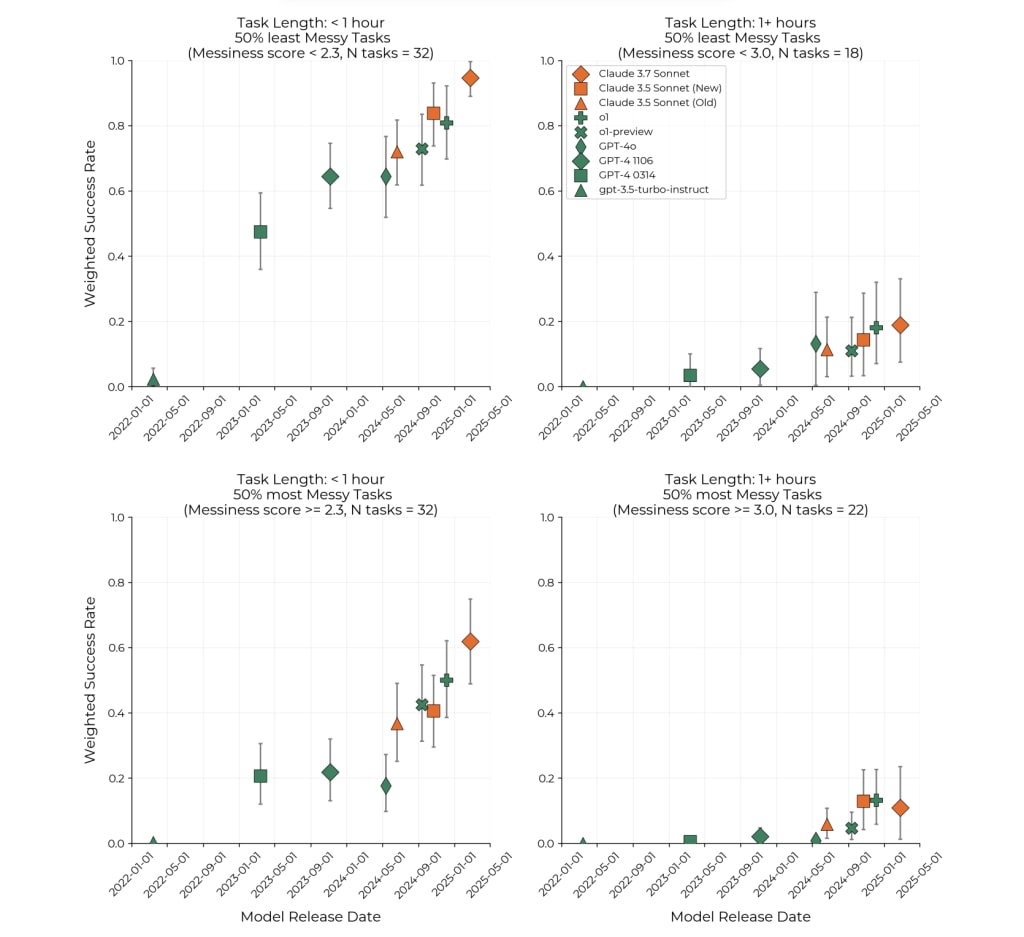

- Messiness somewhat tracks a lack of feedback loops. In METR’s horizon paper, Figure 9 presents the performance of tasks divided into messier and less messy tasks. This performance gap can inform how much a lack of feedback loops will affect performance. One metric we can use is “how far behind is the performance of the more messy tasks?” That is, if we take the maximum of the performance on more messy tasks, how long ago was that performance reached on the less messy tasks?

- For a task length below 1 hour, the max success rate is around 0.6 with Claude 3.7 Sonnet (February 2025). That level was surpassed in November 2023 with GPT-4 1106, making a 15 month gap.

- For a task length above 1 hour, the max success rate on messy tasks is around 0.1 with o1 (Dec 2024) which was surpassed in May 2024 with GPT-4o. That makes a 7-month gap.

- I think the longer tasks are more representative of the types of tasks that will be faced around the feedback loops milestone.

- My gap estimate will add uncertainty on both sides.

Nikola is honest with his readers up front: “The current number is mostly an intuitive guess.” There is not much evidence to be found in what follows, though Nikola is to be commended for his honesty on this front.

Nikola then posits, without justification, that just adding Best-of-K scoring to our evaluation of RE-Bench should take us a third of the way towards crossing the remaining gap, and that this should take between 4-8 months. That gives an estimate of 12-24 months.

This is the majority of Nikola’s positive reasoning, and so far it leaves a good bit to be desired. Nikola then goes on to adjust his estimate downwards based on the view that half of the gap will be already bridged, and that (as Eli suggested) some strategies that worked well on less-vague tasks will generalize well to more-vague tasks.

Nikola then offers a second, largely separate (though in many senses richer) strand of reasoning. Nikola draws on a division in an METR report between “messier” and “less messy” tasks on HCAST and RE-Bench. Nikola looks at the current success rates on messier tasks and asks how long ago the same success rates were achieved on less messy tasks. The gaps are 7 months for longer tasks and 15 months for shorter tasks. Nikola suggests that the 7-month figure is more representative, then adds uncertainty on either side of this figure.

I am not entirely sure whether Nikola’s second strand of reasoning is meant to be driving the estimate, or how it is related to the first strand of reasoning. The first thing to note about Nikola’s reasoning is that it helps itself to some advantageous numbers. Nikola takes the lower of the 7 and 15-month estimates from the METR report (an estimate which also carries a very large error bar). And the METR report only considers performance in 2023 and 2024, which have been atypically good years for progress in artificial intelligence.

More importantly, while the “messiness factors” used in the METR report to determine the messiness of tasks are in many cases reasonable, the HCAST and RE-Bench tasks are not particularly messy. This means that it is not a good idea to estimate the time needed for future AI systems to conquer messy tasks by looking at the time needed to conquer the messier tasks on HCAST and RE-Bench, since many current and future tasks are far messier than these.

All told, the reasoning here is an improvement on Eli’s estimate. After a first “intuitive guess” we are offered a brief attempt at rooting forecasts in empirical data from the METR report. That attempt leaves much to be desired in length and strength. It is, perhaps, a start, but a far cry from what is needed to ground rigorous modeling.

9. Speedups aren’t the main problem

Before concluding, I do want to note one good feature of the benchmarks and gaps model. Namely, one of the more pressing objections to the timeline-extension model becomes less pressing in the context of the benchmarks and gaps model.

We saw in Part 19 of this series how the progress speedups used in the timelines model inappropriately smuggle hyperbolic growth patterns into even purportedly exponential models.

What happens if these speedups are removed? To the authors’ credit, their estimates will be pushed back slightly, but not by enough to shift their qualitative predictions.

Let’s just take a coarse look at the results by assuming RE-Bench saturation in June 2026 (a coarse median for the model’s predictions), then summing each forecaster’s main estimates for the time needed to cross each gap. This isn’t a perfect method, but it is good enough to illustrate the qualitative change.

The table below compares these modified “median” arrival times to the unmodified times given by the authors’ simulations.

| Forecaster | Eli | Nikola | FutureSearch |

| Unmodified Median Time | Dec 2028 | October 2027 | January 2032 |

| Modified “Median” time | January 2030 | March 2029 | September 2032 |

In all cases, predictions have been pushed back. However, the pushback is relatively moderate. While continuing to implement speedups in the takeoff forecast may be more problematic, speedups cannot be the primary problem with the benchmarks-and-gaps model.

10. Conclusion

This post looked at the second of two AI timeline models proposed by the AI 2027 authors. Although this is the authors’ preferred model, we saw that in many respects there is not much of a model here at all. The one primary modeling contribution is a logistic fit to RE-Bench. Even here, we saw that the authors are not sure they should have included this part of the model at all, and that moderate variations of the modeling choices made once a logistic fit is chosen do not do much to shift qualitative model behavior.

After that, we saw that the main contribution is a series of sparsely evidenced forecasts of the dates when a series of milestones will be reached. We saw that there are reasons to be concerned about the reliability of forecasts on this timescale. Reinforcing those concerns, we looked at a case study of the authors’ forecasts for one milestone, in which machines become able to work without externally provided feedback. We saw that some of these forecasts face challenges including sparse evidence and reasoning disconnected from the later quantitative calculations taken to arrive at final estimates. We saw that not all of the reasoning here is bad — in particular, one forecaster does attempt to draw some conclusions about the difficulty of working without external feedback from two years of recent data on messy task performance. But that is not to say that the forecasts meet or approach the level of reliability needed to ground a rigorous model.

We also saw one point of improvement over the timeline-extension model. Whereas the timeline-extension model showed strong effects of modeling choices regarding progress speedups, those effects are less pronounced in the present model. That is why I offered separate arguments against this model.

This concludes my discussion of the AI 2027 timelines report. There are four more reports in this series. I will address some of these reports in future posts.

Note: This essay is cross-posted from the blog Reflective Altruism written by David Thorstad. It was originally published there on August 8, 2025. The account making this post has no affiliation with Reflective Altruism or David Thorstad.

You can leave a comment on this post on Reflective Altruism here. You can read the rest of the post series on existential risk here and the sub-series on AI risk here.

If you notice any formatting errors that are in this post but not in the original, please leave a comment so I can fix them. Thanks.

Seems like a lot of specific, quite technical criticisms. I don't edorse Thorstadts work in general (or not endorse it), but often when he cites things I find them valuable. This has enough material that it seems worth reading.

I think my main disagreement is here:

I weakly disagree here. I am very much in the "make up statistics and be clear about that" camp. I disagree a bit with AI 2027 in that they don't always label their forecasts with their median (which it turns out wasn't 2027 ??).

I think that it is worth having and tracking individual predictions, though I acknowledge the risk that people are going to take them too seriously. That said, after some number of forecasters I think this info does become publishable (Katja Grace's AI survey contains a lot of forecasts and is literally published).

I'm sympathetic to that camp, but I think it has major epistemic issues that largely go unaddressed:

By the way, I find this a strange remark:

This sounds like exactly the sort of criticism that's most valuable of a project like this! If their methodology were sound it might be more valuable to present a more holistic set of criticisms and some contrary credences, but David and titotal aren't exactly nitpicking syntactic errors - IMO they're finding concrete reasons to be deeply suspicious of virtually every step of the AI 2027 methodology.

For e.g. I think it's a huge concern that the EA movement have been pulling people away from nonextinction global catastrophic work because they focused for so long on extinction being the only plausible way we could fail to become interstellar, subject to the latter being possible. I've been arguing for years now, that the extinction focus is too blunt a tool, at least for the level of investigation the question has received from longtermists and x-riskers.

Yeah, I think you make good points. I think that forecasts are useful on balance, and then people should investigate them. Do you think that forecasting like this will hurt the information landscape on average?

Personally, to me, people engaged in this forecasting generally seem more capable of changing their minds. I think the AI2027 folks would probably be pretty capable of acknowledging they were wrong, which seems like a healthy thing. Probably more so than the media and academic?

Sure, so we agree?

(Maybe you think I'm being derogatory, but no, I'm just allowing people who scroll down to the comments to see that I think this article contains a lot of specific, quite technical criticisms. If in doubt, I say things I think are true.)

Ah, sorry, I misunderstood that as criticism.

I'm a big fan of the development e.g. QRI's process of making tools that make it increasingly easy to translate natural thoughts into more usable forms. In my dream world, if you told me your beliefs it would be in the form of a set of distributions that I could run a monte carlo sim on, having potentially substituted my own opinions if I felt differently confident than you (and maybe beyond that there's still neater ways of unpacking my credences that even better tools could reveal).

Absent that, I'm a fan of forecasting, but I worry that overnormalising the naive I-say-a-number-and-you-have-no-idea-how-I-reached-it-or-how-confident-I-am-in-it form of it might get in the way of developing it into something better.

I dunno, I think that sounds galaxy-brained to me. I think that giving numbers is better than not giving them and that thinking carefully about the numbers is better than that. I don't really buy your second order concerns (or think they could easily go in the opposite direction)

Executive summary: This reflective, critical post argues that the AI 2027 “benchmarks and gaps” timelines model is not meaningfully better than the authors’ earlier model, because it relies heavily on sparse, subjective forecasts and weakly justified modeling choices that are more likely to reflect systematic bias than to provide reliable information about AI timelines.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.