The next technological revolution could come this century and could last less than a decade

This is a quickly written note that I don't expect to have time to polish.

Summary

This note aims to bound reasonable priors on the date and duration of the next technological revolution, based primarily on the timings of (i) the rise of homo sapiens; (ii) the Neolithic Revolution; (iii) the Industrial Revolution. In particular, the aim is to determine how sceptical our prior should be that the next technological revolution will take place this century and will occur very quickly.

The main finding is that the historical track record is consistent with the next technological revolution taking place this century and taking just a few years. This is important because it partially undermines the claims that (i) the “most important century” hypothesis is overwhelmingly unlikely and (ii) the burden of evidence required to believe otherwise is very high. It also suggests that the historical track record doesn’t rule out a fast take-off.

I expect this note not to be particularly surprising to those familiar with existing work on the burden of proof for the most important century hypothesis. I thought this would be a fun little exercise though, and it ended up pointing in a similar direction.

Caveats:

- This is based on very little data, so we should put much more weight on other evidence than this prior

- I don’t think this is problematic for arguing that the burden of evidence required to think a technological revolution this century is likely is not that high

- But these priors probably aren’t actually useful for forecasting – they should be washed out by other evidence

- My calculations use the non-obvious assumption that the wait times between technological revolutions and the durations of technological revolutions decrease by the same factor for each revolution

- It’s reasonable to expect the wait times and durations to decrease, e.g. due to increased population, better and faster growth in technology (note though that this reasoning sneaks some extra information into the prior though)

- Indeed, the wait time and duration for the Neolithic revolution are larger than those of the Industrial revolution

- With just two past technological revolutions, we don’t have enough data to even “eye-ball” whether this assumption roughly fits the data, let alone test it statistically

- Decreasing by the same factor each time seems like the simplest assumption to make in this case and it’s consistent with more complex but—I think—natural assumptions, about technological revolutions arriving as a Poisson process, and the population growth rate being proportional to the population level

- For the purposes of determining the burden of proof on the most important century hypothesis, I’m roughly equating “will this be the most important century?” with “will there be a technological revolution this century?”

- These obviously aren’t the same but I think there are reasons to think that if there is a technological revolution this century, it could be the most important century, or at least the century that we should focus on trying to influence directly (as opposed to saving resources for the future)

Timing of next technological revolution

There have been two technological revolutions since the emergence of homo sapiens (about 3,000 centuries ago): the Neolithic Revolution (started about 100 centuries ago) and the Industrial Revolution (started about 2 centuries ago).

Full calculations in this spreadsheet.

- Homo sapiens emerged about 300,000 years ago (3,000 centuries)

- Neolithic revolution was about 10,000 years ago (100 centuries ago and 2,900 centuries after the start of homo sapiens)

- Started 100-120 centuries ago

- Took about 20 centuries in a given location

- Finished about 60 centuries ago

- So the wait was about 2,880-2,900 centuries

- Industrial revolution was about 200 years ago (2 centuries ago)

- 98-118 centuries after the start of the neolithic revolution

- 78-98 centuries after the end of the neolithic revolution in the original place

- 58 centuries after the end of the neolithic revolution

- log10(2900/88)≈1.5, i.e. the wait was 1.5 OOMs shorter for the second revolution than the first

- If the wait is 1.5 OOMs shorter again, this suggests the next revolutionary technology will arrive about 3 centuries after the industrial revolution (3 is ~1.5 OOMs smaller than 100), i.e. in about 1 century

- More precisely: the next revolution comes about 88×88/2900≈2.7 centuries after the Industrial revolution, in about 70 years

- So we’re almost due a revolutionary technology! (According to this simple calculation.)

- Is this a sensible calculation? I think it's not crazy. It seems like the wait between technological revolutions should decrease each time, given that population is growing. The assumption that the wait decreases by the same factor each time is simple.

- This assumption is also consistent with technological revolutions arriving as a Poisson point process, with time counted in human-years, and with population growth rate proportional to population level (more later).

- Shouldn’t put much weight on this relative to other evidence, but history doesn’t rule out the next technological revolution coming very soon

Duration of the next technological revolution

Full calculations in the spreadsheet.

- Neolithic revolution took about 2000 years in a given location (not researched thoroughly)

- Most sources say it took several thousand years, but this includes the time it took for agricultural technology to diffuse from the initial regions in which it arose or to be reinvented in other regions

- Industrial revolution took about 80 years in Britain

- I think the lengths of time for the initial revolutions (or later but independent revolutions) in confined regions is the relevant comparison, not how long it took for revolutionary technology to diffuse, since we care about when the next technological revolution happens somewhere at all

- Decrease by about 1.4 OOMs

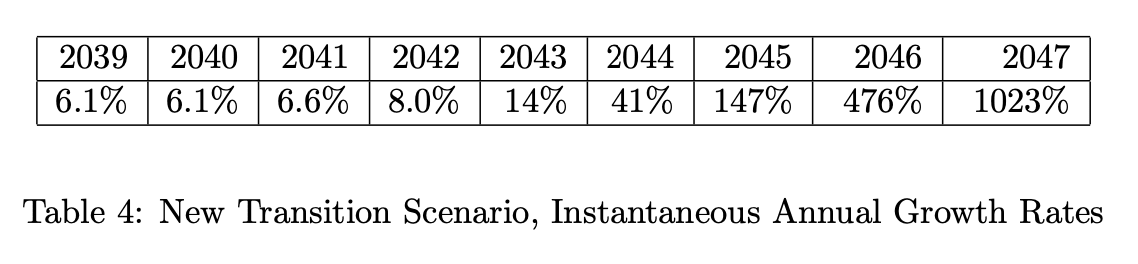

- Suggests the next technological revolution will take about 802/2000≈3 years

- The 2000 year number is very rough but if it took only 200 years, then we’d expect the next technological revolution to take about 30 years – not a huge difference

- Same (or even stronger) caveats as above apply, history doesn’t rule out the next technological revolution taking just a few years

Poisson process on the number of human-years

Suppose technological revolutions arise as a Poisson point process, with time measured in human-years, so that it takes the same number of human-years for each technological revolution (on average). This seems like a reasonable way to form a prior in this case. If it takes N human-years for a technological revolution on average, and the number of human-years has been growing exponentially, then the time between each multiple of N should get shorter. But population hasn’t grown at a constant exponential rate, it’s more like the growth rate is proportional to the population level (until very recently, in macrohistorical terms).

Numerical simulations suggest that when population growth is proportional to population level, the time delay between each N human-years gets shorter by the same factor each time.

Are there any experiments offering sedatives to farmed or injured animals?

A friend mentioned to me experiments documented in Compassion, by the Pound in which farmed chickens (I think broilers?) prefer food with pain killers to food without pain killers. I thought this was super interesting as it provides more direct evidence about the subjective pain experienced by chickens than merely behavioural experiments, via a a plausible biological mechanism for detecting pain. This seems useful for identifying animals that experience pain.

Identifying some animals that experience pain seems useful. Ideally we would be able to measure pain in a way that lets us compare the effects of potentially welfare-improving interventions. It might be particularly useful to identify animals whose pain is so bad they'd rather be unconscious, suggesting their lives (at least in some moments) are worse than non-existence. I wonder if similar experiments with sedatives could provide information about whether animals prefer to be conscious or not. For example, if injured chickens consistently chose to be sedated, this would provide moderate evidence that their lives are worse than non-existence. (Conversely, failure to prefer sedatives to normal food or pain killers seems weaker evidence against this, but still informative.)

Invertebrate sentience table (introduced here) has "Self-administers analgesics" as one of the features potentially indicative of phenomenal consciousness. But it's only filled for honey bees, chickens, and humans. I agree that more such experiments would be useful. It's more directly tied to what we care about (qualia) than most experiments.

I think that animals might not eat painkillers until they are unconscious out of their survival instinct. There are substances that act as painkillers in nature, and the trait "eat it until you're unconscious" would be selected against by natural selection. But if they would eat it until unconscious, that would provide good evidence that their lives are worse than non-existence.

Very cool. You may have seen this but Robin Hanson makes a similar argument in this paper.