The views expressed here are my own.

Summary

- I estimate the improvement in cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation is worth it for a net income above 15.5 k$/year.

- I think creatine supplementation is beneficial, although I do not know if cost-effective, ignoring improvements in overall cognitive function. According to the systematic review of Kreider and Stout (2021), “it can be concluded that creatine supplementation has several health and therapeutic benefits throughout the lifespan”.

Break-even analysis

I estimate the improvement in cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation is worth it for a net income above 15.5 k$/year. I calculate this from the ratio between:

- A cost of creatine supplementation of 119 $/year, respecting:

- Powder, which is 116 $/year cheaper than capsules under my assumptions.

- A financial cost of 0.214 $/d for 0.0713 $/g and 3 g/d.

- A time cost of 0.167 $/d for 30 s/d and 20 $/h.

- A relative increase in net income caused by creatine supplementation of 3 g/d of 0.897 %. I get this multiplying:

- An improvement in the overall cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation of “1 IQ [intelligence quotient] point”, as calculated in Sandkühler et al. (2023) for improvements in Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) for a “daily supplementation of 5 g for 6 weeks”.

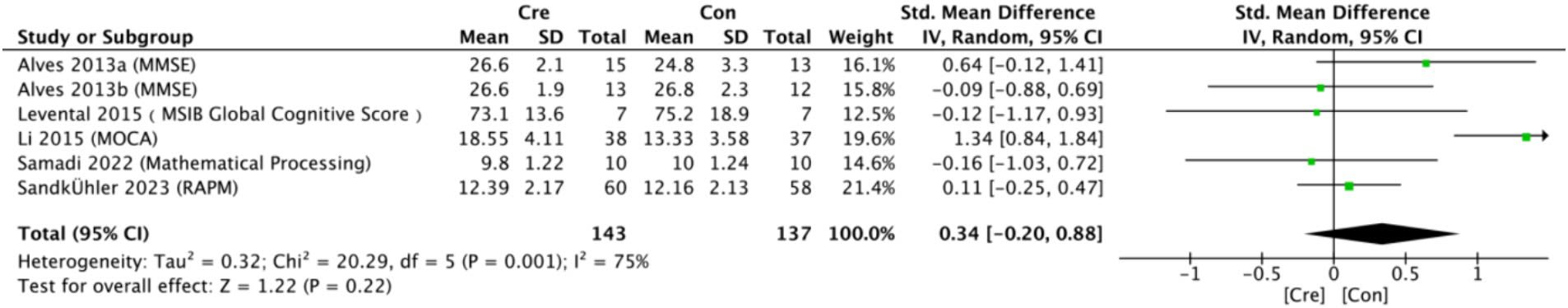

- Xu et al. (2024) meta-analysed 6 randomised controlled trials assessing the effect of creatine supplementation on overall cognitive function, including Sandkühler et al. (2023), and the standardised mean difference respecting this is 32.4 % (= 0.11/0.34) of that linked to their meta-analytic estimate (see Figure 3).

- Sandkühler et al. (2023), which was linkposted on the EA Forum, is a randomised, double-bind, placebo-controlled, and preregistered trial. None of the other 5 studies meta-analysed in Xu et al. (2024) with respect to overall cognitive function were preregistered.

- I assume the improvement in cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation does not decay over time. From the systemic review of Kreider et al. (2017), "significant health benefits may be provided by ensuring habitual low dietary creatine ingestion (e.g., 3 g/day [my assumed dosage]) throughout the lifespan".

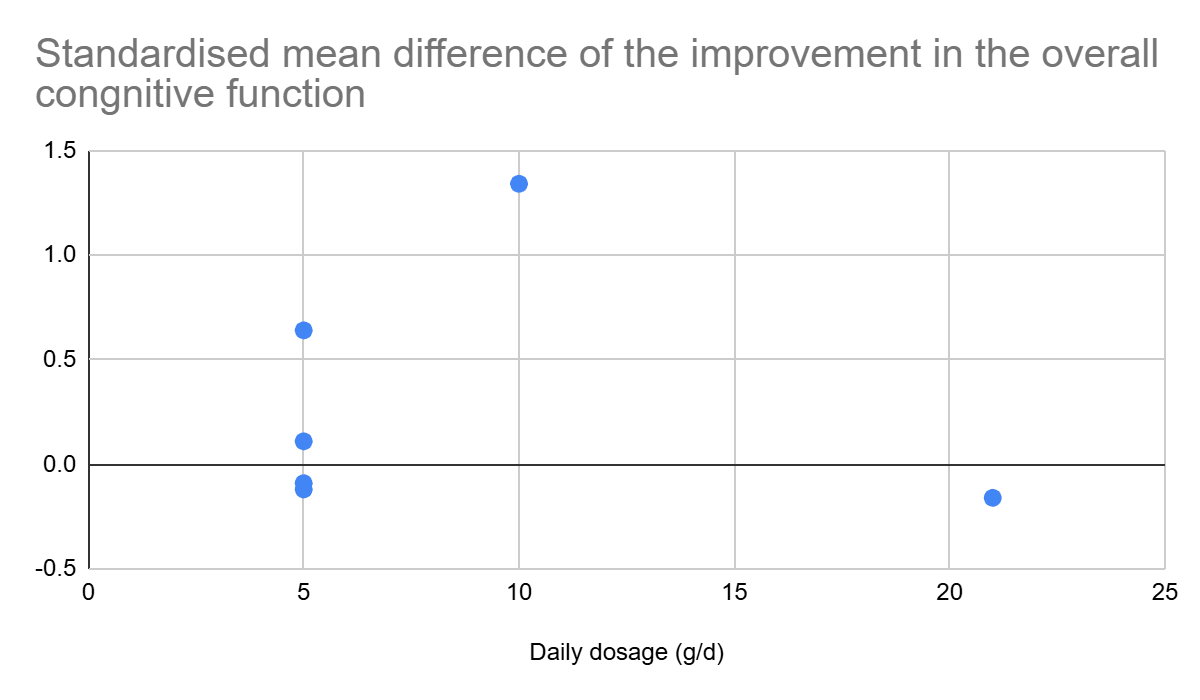

- A dosage adjustment factor of 77.4 %. I obtain this for my assumed lower dosage of 3 g/d guessing the improvement in the overall cognitive function is proportional to the logarithm of 1 plus the daily dosage in g/d.

- An increase in net income of 1.16 % per additional IQ point. This is the effect of national IQ on education- and age-adjusted wages of immigrants in the United States found by Jones and Schneider (2010) (see Table 1).

- The result is in line with other literature. "We show that a country’s average IQ score is a useful predictor of the wages that immigrants from that country earn in the United States, whether or not one adjusts for immigrant education. Just as in numerous microeconomic studies, 1 IQ point predicts 1% higher wages, suggesting that IQ tests capture an important difference in crosscountry worker productivity".

- An improvement in the overall cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation of “1 IQ [intelligence quotient] point”, as calculated in Sandkühler et al. (2023) for improvements in Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) for a “daily supplementation of 5 g for 6 weeks”.

Discussion

Xu et. al (2024) estimated a 95 % confidence interval for the improvement in the overall cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation of 0.0980 to 0.570 pooled standard deviations (Hedge’s g), or 29.3 % (= 0.0980/0.334) to 171 % (= 0.570/0.334) of their best estimate. Using these to adjust my mainline result, the improvement in cognitive function caused by creatine supplementation is worth it for a net income above 9.06 k (= 15.5*10^3/1.71) to 52.9 k$/year (= 15.5*10^3/0.293).

I wanted to estimate the benefits of creatine supplementation from studies looking into its effect on net income, but I did not find them. So I relied on the effect of creatine supplementation on cognitive function, and of increasing IQ on wages.

Sandkühler et al. (2023) “found no indication that our vegetarian participants benefited more from creatine than our omnivore participants (in fact, the creatine effect was smaller in vegetarians than omnivores to a non-statistically significant extent). This is in line with Solis et al. [22, 24] who did not find a difference in brain creatine content between omnivores and vegetarians”.

I think creatine supplementation is beneficial, although I do not know if cost-effective, ignoring improvements in overall cognitive function. According to the systematic review of Kreider and Stout (2021), “it can be concluded that creatine supplementation has several health and therapeutic benefits throughout the lifespan”.

I liked Antonio et al. (2021), “Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show?”.

Based on our evidence-based scientific evaluation of the literature, we conclude that:

- Creatine supplementation does not always lead to water retention.

- Creatine is not an anabolic steroid.

- Creatine supplementation, when ingested at recommended dosages, does not result in kidney damage and/or renal dysfunction in healthy individuals.

- The majority of available evidence does not support a link between creatine supplementation and hair loss / baldness.

- Creatine supplementation does not cause dehydration or muscle cramping.

- Creatine supplementation appears to be generally safe and potentially beneficial for children and adolescents.

- Creatine supplementation does not increase fat mass.

- Smaller, daily dosages of creatine supplementation (3-5 g or 0.1 g/kg of body mass) are effective. Therefore, a creatine ‘loading’ phase is not required.

- Creatine supplementation and resistance training produces the vast majority of musculoskeletal and performance benefits in older adults. Creatine supplementation alone can provide some muscle and performance benefits for older adults.

- Creatine supplementation can be beneficial for a variety of athletic and sporting activities.

- Creatine supplementation provides a variety of benefits for females across their lifespan.

- Other forms of creatine are not superior to creatine monohydrate.

My financial cost of capsules was 3 times as high as it should be. I thought the 3 g of creatine mentioned in the nutritional composition were the amount per capsule, whereas they were the amount per 3 capsules. Now powder looks 116 $/year cheaper than capsules for a time cost of 30 s/d (instead of my original assumption of 20 s/d).

I have updated to reflect using powder with the updated time cost. The updated break-even net income is 15.5 k$/year, 1.46 (= 15.5*10^3/(10.6*10^3)) times my original value.