Note: I am not a malaria expert. This is my best-faith attempt at answering a question that was bothering me, but this field is a large and complex field, and I’ve almost certainly misunderstood something somewhere along the way.

Summary

While the world made incredible progress in reducing malaria cases from 2000 to 2015, the past 10 years have seen malaria cases stop declining and start rising. I investigated potential reasons behind this increase through reading the existing literature and looking at publicly available data, and I identified three key factors explaining the rise:

- Population Growth: Africa's population has increased by approximately 75% since 2000. This alone explains most of the increase in absolute case numbers, while cases per capita have remained relatively flat since 2015.

- Stagnant Funding: After rapid growth starting in 2000, funding for malaria prevention plateaued around 2010.

- Insecticide Resistance: Mosquitoes have become increasingly resistant to the insecticides used in bednets over the past 20 years. This has made older models of bednets less effective, although they still have some effect. Newer models of bednets developed in response to insecticide resistance are more effective but still not widely deployed.

I very crudely estimate that without any of these factors, there would be 55% fewer malaria cases in the world than what we see today. I think all three of these factors are roughly equally important in explaining the difference.

Alternative explanations like removal of PFAS, climate change, or invasive mosquito species don't appear to be major contributors.

Overall this investigation made me more convinced that bednets are an effective global health intervention.

Introduction

In 2015, malaria rates were down, and EAs were celebrating. Giving What We Can posted this incredible gif showing the decrease in malaria cases across Africa since 2000:

The reduction in malaria has been caused — in large part — by people sleeping under bednets…Long lasting insecticide-treated bednets are a powerful weapon against malaria, not only because they’re a physical barrier between mosquitoes and sleeping children — the insecticide coating kills mosquitoes, so they don’t infect other members of the family (and the village) who don’t have mosquito nets…

In other words, this paper tells us about the bigger picture, showing that bednets are incredibly effective, not just at the level of individual villages, but at the level of whole populations. Essentially, the case that we should be distributing bednets just got even stronger.

SlateStarCodex said that “Humanity seems to be very visibly winning the war against malaria. I just donated a thousand more bednets; now I feel like a part of it and one day I can tell my kids that I helped.”

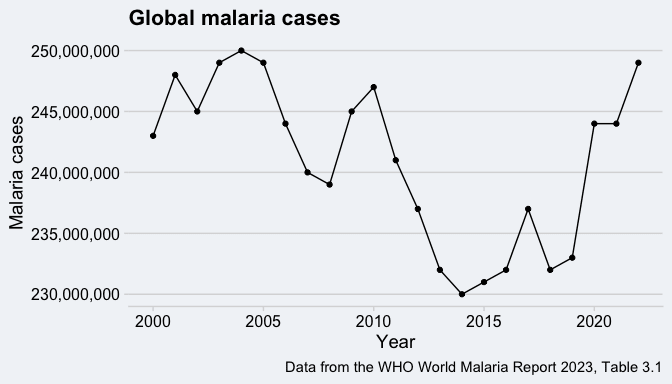

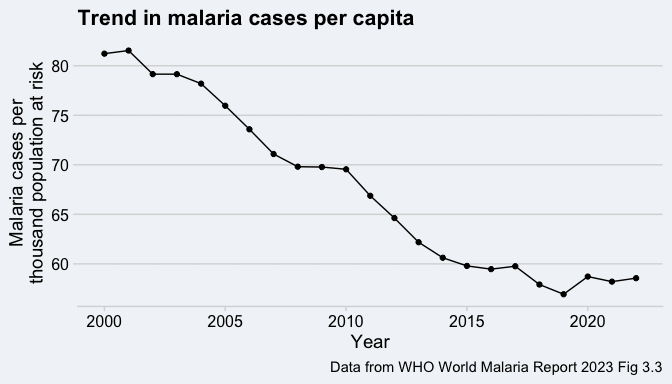

Unfortunately, 2015 would prove to be a turning point, and by 2022, worldwide malaria cases are as high as they have ever been[1]:

If the decline in malaria cases from 2000 to 2015 strengthened the cases for bednets, does the increase from 2015 to 2022 weaken it? Did all our bednets stop working in 2015? Did everyone get a secret memo saying the bednets were no longer for sleeping under and should instead be used for fishing?

After diving into this, I think the increase in malaria cases is caused by 3 things, only one of which is bednets becoming less effective:

- Growing population in countries with malaria

- Stagnant funding levels since 2010

- Increased insecticide resistance in mosquitoes

Ok, give me the 1 minute rundown on what malaria is and how we fight it?

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by the Plasmodium parasite and spread by mosquitoes. While it can be transmitted through infected blood (including from mother to fetus during pregnancy), that is rare and it doesn’t usually spread from person to person. Malaria is both preventable and treatable, but nonetheless was responsible for approximately 9% of all deaths in children under 5 in 2021.

Malaria is widespread throughout the tropics, but the vast majority of cases are in sub-Saharan Africa. The WHO estimates that in 2022, 90% of global malaria cases were in Africa and 40% were in just two countries: Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Preventing malaria has historically meant distributing bednets

While there are many approaches to preventing malaria (including 2 newly-approved malaria vaccines, spraying pesticides, seasonal malaria chemoprevention, and removing mosquito habitats), the bulk of international funding for malaria prevention has historically gone to bednets treated with insecticide (These are also called ITNs, insecticide-treated nets, or LLINs, long-lasting insecticidal nets[2]). These nets prevent malaria in two ways:

- Mosquitoes can’t bite people sleeping under nets, and therefore can’t give them malaria.

- The insecticide in the nets also kills mosquitoes. After a mosquito bites someone with malaria it takes several days before they can transmit it to someone new. If the mosquito dies during that time period, they can’t transmit malaria.

A bednet is usually assumed to last for 3 years, although in reality it’s more common for them to last closer to 2 years.

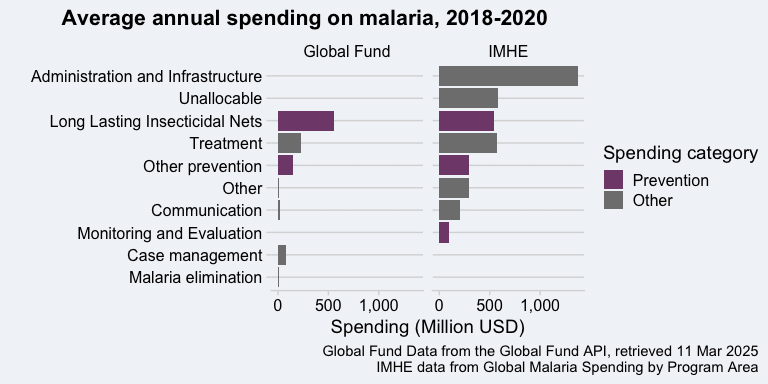

Tracking down how much money is spent on bednets globally is difficult. In the end I found two different sources for looking at this:

- Data on how the the Global Fund spends money on malaria

- Estimates from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IMHE) on how all governments and non-profits spend money on malaria.

In theory, the Global Fund data should be a subset of the IMHE data, but I decided to look at both because they are different things. The Global Fund data is a direct report of how one organization distributed its funds. The IMHE data is a combined estimate of how money from all organizations was actually spent on the ground. Here are the results broken down by spending category:

Both sources agree that bednets are the largest component of spending on prevention, but past that there are some large differences. Some of that is to be expected because Global Fund spending is just a part of what’s included in the IMHE estimates, but I think some of it also comes down to differences in accounting. I think some spending that the Global Fund would categorize as being spent on bednets IMHE is categorizing as administration of infrastructure. Either way, bednets account for the majority of all funding for preventing malaria.

There’s a lot of good evidence showing that bednets have been effective at preventing malaria

I won’t focus on it here, but there’s a strong base of evidence that bednets were historically effective at preventing malaria. There’s the physical evidence of decline cases from 2000 to 2015, just as bednet usage surged across Africa. There’s the Cochrane Review from 2018 that concluded that insecticidal treated nets reduce the number of malaria cases per year and reduce all-cause mortality in children. More recently, two randomized control trials (2019 and 2020) looked at the effectiveness of “next-generation” bednets, and found that they reduced the number of malaria cases in children by close to 50% compared to the previous generation of bednets. Scott Smith has a nice forum post looking at the cost-effectiveness of the newest bednets in a lot more detail.

For this post, I’m therefore going to be taking it for granted that the steep decline in malaria cases from 2000 to 2015 was caused by the spread of bednets and other preventative measures. The question I’m interested in is why that decline stopped in 2015.

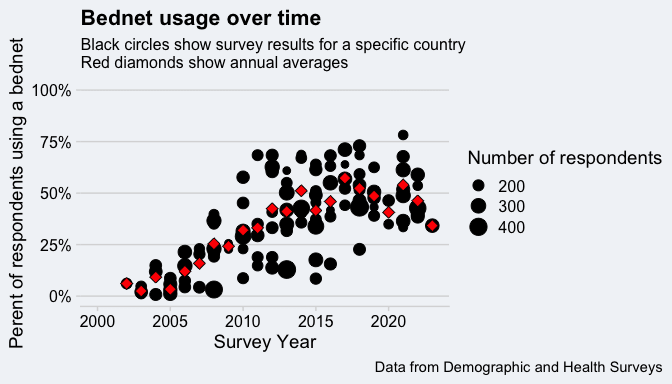

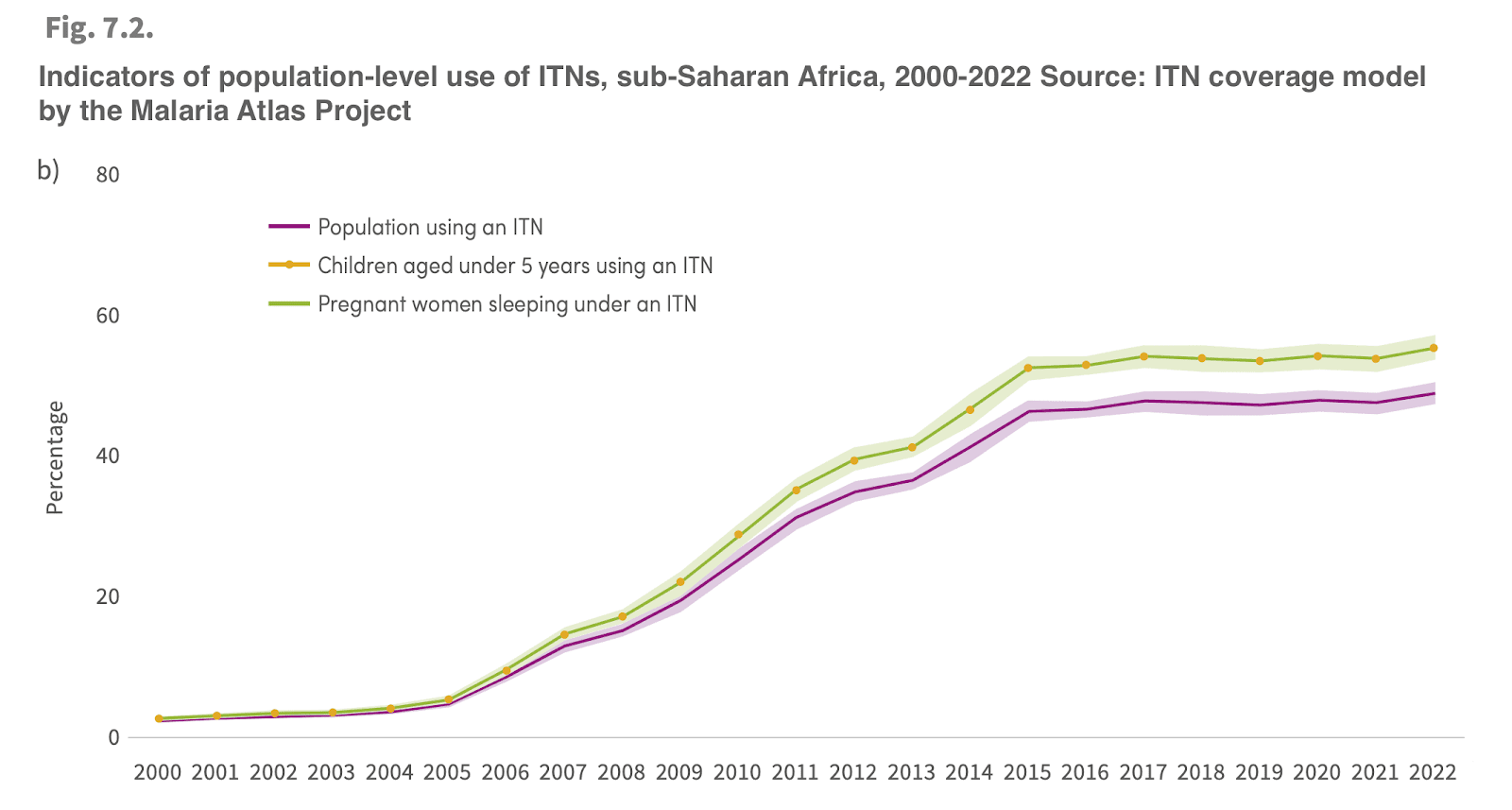

The percent of people with access to bednets and the percent of people sleeping under bednets have both stayed constant or increased since 2015

Given the sudden turnaround in malaria cases in 2015 and the importance of bednets to preventing malaria, a natural assumption is that people in areas with malaria either no longer have access to bednets or are no longer sleeping under them. That does not appear to be the case. We actually have a really nice data source for this from the Demographic and Health Surveys, which have been asking about bednet access and usage in different countries for 20+ years. If you take all the surveys from sub-Saharan Africa and just look at the trend over time, you see a huge rise from 2000 to 2015 and a constant (but noisy) trend since then:

If you do some more complicated modeling to try to estimate usage in countries between surveys, you get the same picture according to the WHO and the Malaria Atlas Project:

These results are all based on surveys, so “using a bednet” means that in a survey, a respondent said that they slept under a bednet the night before. So it’s possible that these results are biased and there actually is a decreasing trend in usage over time, but I think the simpler explanation is that bednet usage is staying the same.

So what did cause the increase in malaria cases since 2015?

As I said at the beginning, I think the increase in malaria cases is caused by increased population, stagnant funding, and insecticide resistance. It’s your classic multi-factoral trend. I’m highly confident that each of these three factors plays some role in the growth of cases; I’m less confident that these are the only three major factors. I’ve looked at a number of other factors and concluded that they aren’t major players, but it’s always possible that I’ve neglected or mis-interpreted something. In a world where none of these things were true, I think there would be 100 million malaria cases in the world per year rather than the 250 million we actually see. I think population growth is responsible for 34% of the difference, the slowdown in funding growth for 27%, and insecticide resistance for 39% (but all of those numbers have huge uncertainties associated with them).

I’ll look at the evidence for each factor in turn, and then look at how much each one contributed to the rise in cases at the end.

Factor 1: Population increase

If, like me, you’re more used to working with public health data from the US or Europe, it’s easy to underestimate how much the population of Africa has increased in the last 20 years. The population of Africa has increased by roughly 75% since 2000. Over that same time, the population of the US has increased by about 20% and Europe by 2%.

This is probably also a good place to point out that basically any statistics for the DRC, Nigeria, and most other countries with the highest rates of malaria are extremely uncertain. For example, there are concerns that the population of Nigeria may be overestimated by 25%. For this post, I’m taking the estimated numbers of malaria cases and deaths from the WHO at face value, but it’s worth keeping in mind that these are not counted, but are rather modeled based on malaria parasite prevalence. I didn’t dive into how the WHO comes up with these estimates.

If you look at malaria cases per capita, rather than the absolute number of cases, the picture changes:

Instead of a rebound, rates of malaria cases have basically stayed flat since 2015, after a strong decrease from 2000–2015. But is cases per capita really the right metric? For an infectious disease like COVID or flu, doubling the population could lead to an exponential rise in the number of cases (as each person can spread the disease to twice as many people, who then each spread the disease to twice as many people, etc., etc.). But because malaria hopscotches back and forth between mosquitoes and people, its transmissions dynamics are more complicated. If each mosquito is spreading malaria just as fast as it can, then it’s possible that doubling the human population might not change the number of malaria cases at all.

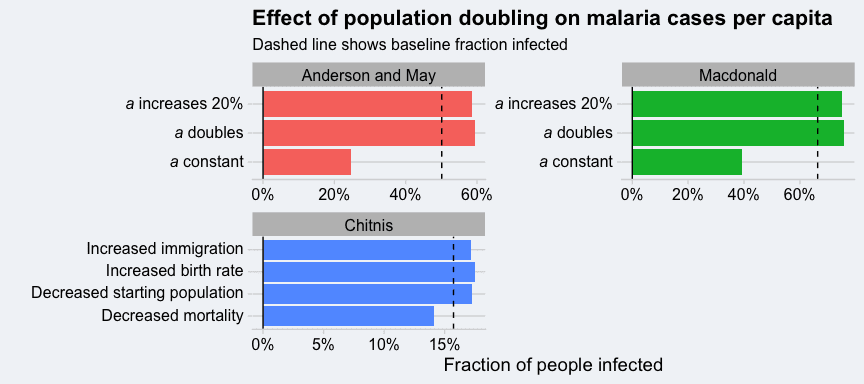

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any papers looking explicitly at how overall population affects malaria rates. I did find some papers describing more general models of malaria transmission, and I used those to explore how changing population changes malaria cases per capita.

Probably the most applicable model I found was one described in Chitnis et al., 2008. This was the simplest malaria model I found that allowed the human population to vary over time. It also explicitly models the rate of mosquito-human biting as a function of population and appears to do a very thorough job of determining reasonable values for the parameters that go into their model. The model doesn’t have an explicit “how many people” parameter, but it does have inputs for the starting number of people, the birth rate, the death rate, and the immigration rate which I futzed around with until I got roughly a factor of 2 change in the population.

I also looked at two other older models of malaria transmission: the Macdonald model and the Anderson and May model. These models don’t explicitly keep track of the mosquito and human populations, but they do have a parameter for the number of mosquitoes per person. They also have a parameter (a) for the average number of times each mosquito bites any person each day. This ends up being a crucial parameter in these models, and its behavior when you double the population isn’t specified by the model. If there are far more mosquitoes than humans, then doubling the human population will cause a to double. But if there are far more humans than mosquitoes, then doubling the human population will cause no change in a (because mosquitoes are already biting humans as much as they can). So I tried three scenarios: a doubles, a stays the same, and a increases 20% (what you get using the Chitnis model).

The results for all three models are shown below[3]. Each scenario for each model is shown as a different bar, and the x-axis shows the fraction of people infected with malaria after letting the models reach steady state. The dashed line shows the fraction of people infected with malaria before we doubled the population. For the Chitnis model, no matter how you double the population, the fraction of people infected stays about the same. For the other two models, if a doubles or increases a little, then the fraction of people infected doesn’t change by much. But if a stays the same as the population increases then the fraction of people infected drops by close to half. However, as previously discussed, we would only expect a to stay the same as the population doubles if there are far more humans than mosquitoes. In the areas where malaria is most prevalent, this is unlikely to be the case.

Based on these results, my best guess is that doubling the human population, while keeping other factors the same, would lead to the number of malaria cases doubling and the cases per capita to stay approximately the same.

Factor 2: Stagnant funding

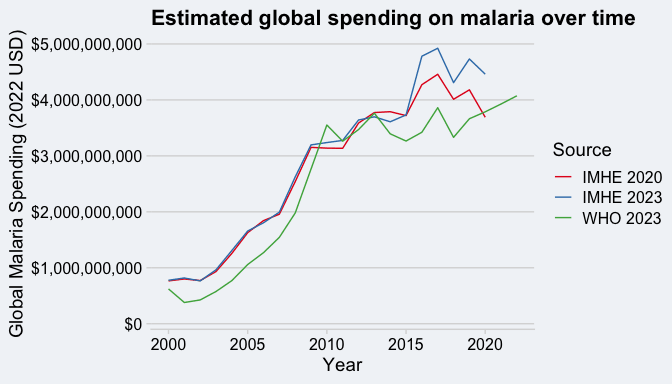

“How much money do we spend on malaria” is the sort of question that sounds simple but ends up being extremely complicated to answer. As best as I can tell, the only groups that try to answer this are the WHO and IMHE. Depending on which group and which version of the data you look at, you get different numbers for how funding for malaria has changed over time.

All of the spending numbers that I’m going to show are adjusted for inflation and do not include personal spending on malaria treatment or spending on malaria-related R&D. Both the WHO and IMHE break down their spending into 2 big categories: spending by the governments of affected countries, and what the IMHE calls “development assistance for health”, basically foreign aid. IMHE is very clear that they try to track down money spent by non-governmental charities, while the WHO is a little fuzzier on what they include. I know that the WHO includes spending from the Gates Foundation and money channeled through the Global Fund, but I don’t know if they include spending from other NGOs.

I came up with three estimates of global spending on malaria from these two groups: the WHO 2023 World Malaria Report estimate (WHO 2023), the IMHE 2020 Global Malaria Spending estimate (IMHE 2020), and an estimate I put together combining government spending from the IMHE 2020 Global Malaria Spending estimate with data from the IMHE 2023 Development Assistance for Health Database (IMHE 2023). Here’s what the trends for each of them look like:

The WHO and IMHE agree that something changed around 2010, but disagree on whether funding growth stopped completely or just slowed down. WHO shows funding being close to flat since 2010, or maybe increasing by $0.5 billion if you’re generous. IMHE 2020 and IMHE 2023 show an increase of closer to $1 billion between 2010 and 2020, with a peak in 2017 and a decrease since then. I don’t know what accounts for the discrepancy, but if IMHE really does do a better job of tracking down NGO money, that might explain the difference

Change in global malaria spending according to IMHE and WHO

| Source | Change 2001-2011 | Change 2011-2019 |

|---|---|---|

| IMHE 2020 | $2.5 Billion (322%) | $0.6 Billion (20%) |

| IMHE 2023 | $2.6 Billion (330%) | $1.2 Billion (36%) |

| WHO 2023 | $3 Billion (621%) | $0.4 Billion (11%) |

Other, less comprehensive sources I’ve been able to find back this up as well. US foreign spending on malaria, from foreignassistance.gov, shows funding growing from near nothing in 2005 to $750 million in 2015 and basically no growth since then. The WHO Global Health Expenditure Database (GHED) only goes back to 2013, and it shows basically constant spending on malaria. There’s also a paper by Haakenstad et al. that comes up a lot when you google for this (and shows complete funding stagnation since 2009), but it uses a 2017 version of data from IMHE that I think is superseded by the 2020 or 2023 versions.

Given that a change in funding growth occurred in 2010, when would we expect to see that show up in the number of malaria cases per capita? My best estimate is that changes in funding levels take about 3-5 years to be reflected in malaria cases, for two reasons:

- Both mosquitoes and the malaria parasite have lifespans of under a month, so it only takes a couple months for them to reach a new equilibrium when conditions change. People and our organizations are the slow moving step here.

- The bulk of this funding goes towards purchasing bednets, with an effective lifespan of about 3 years. Add in about another year to get the bednets to the people who need them, and a single funding decision influences malaria rates for approximately 4 years.

That matches very well with what we see, where a change in funding growth happened around 2010 and cases per capita leveled off around 2015. The fact that we see a total leveling off of cases per capita when funding has slowly increased (at least according to the IMHE numbers) suggests that the cost effectiveness of funding has been decreasing over time. That could be because of insecticide resistance (discussed in the next section); it could be because population growth means you need more funding for the same effect; or it could be simply because eliminating the last case of malaria is harder than eliminating the first case.

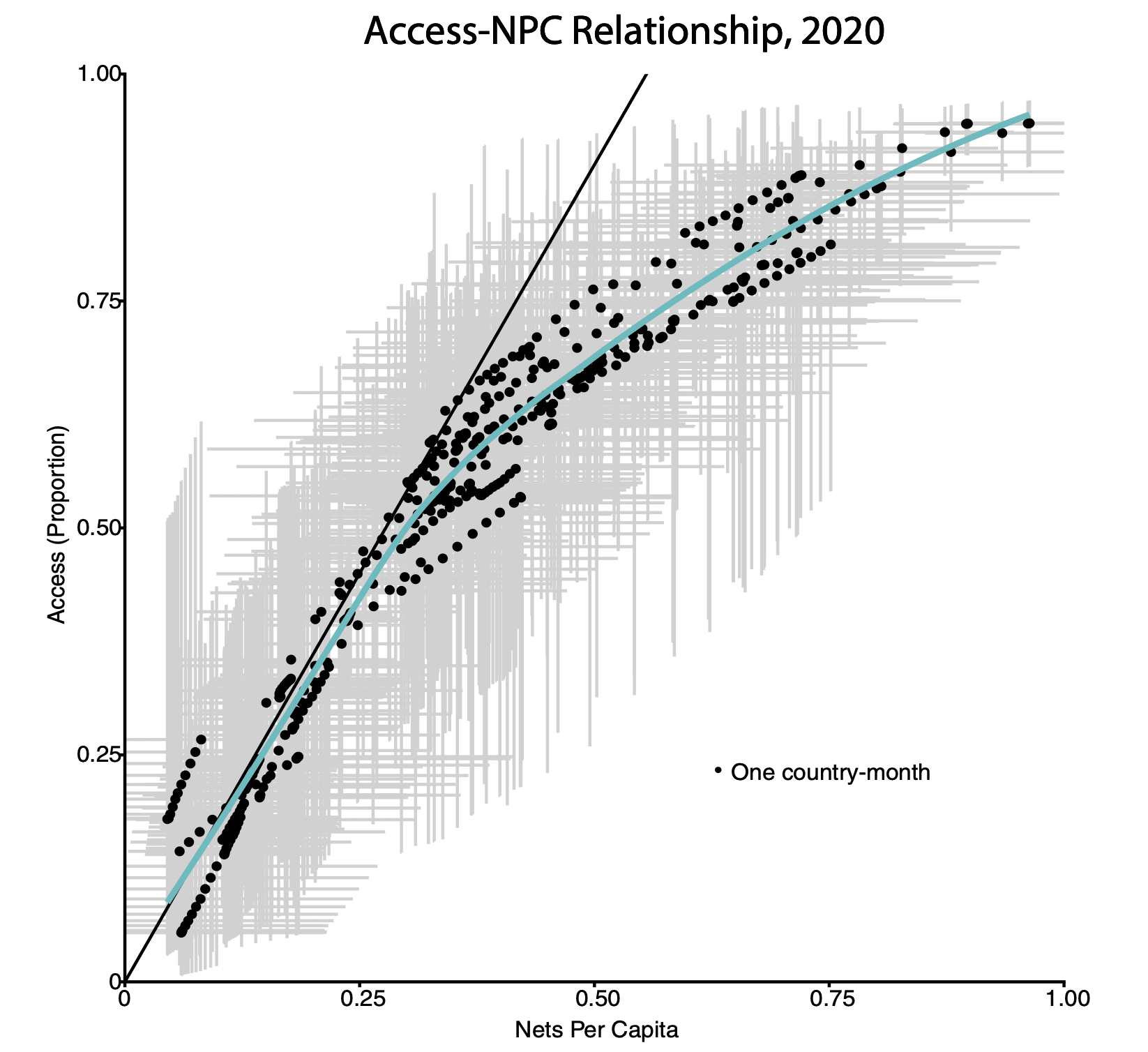

We actually have some empirical evidence for the last hypothesis. Bertozzi-Villa et al., 2024 did some sophisticated modeling of bednet distribution and access across sub-Saharan Africa. They used those models to produce this graph comparing nets per capita in a country with the percent of people who have access to a bednet:

They find a sub-linear relationship, showing that the more people who already have bednets, the more bednets you need to distribute in order to raise access by the same amount. That’s probably intuitive, but it’s nice to have confirmation.

Factor 3: Insecticide resistance

Just like bacteria evolve to become resistant to the antibiotics we use most frequently, mosquitoes evolve to become resistant to the insecticides we use.

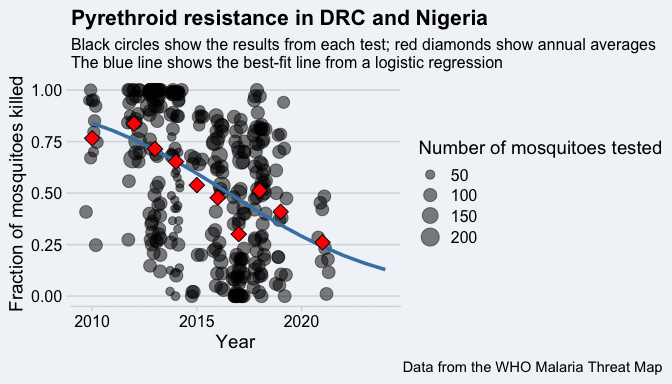

The WHO has a standardized method for seeing if mosquitoes are resistant to different classes of insecticides, which is basically putting a bunch of mosquitoes in a tube with the insecticide and seeing how many of them are killed. Here are all the results for the fraction of mosquitoes that are susceptible to pyrethroids (the main insecticide in bednets) in the DRC and Nigeria:

The fraction of mosquitoes killed in these tube tests dropped by over a factor of 3 between 2010 and 2021. Given that pyrethroids are the most common insecticide in bed nets, this is a major problem. It’s not quite as bad as it looks from this graph though, because net manufactures and distributors are adapting to this. In the past, this meant adding the chemical PBO to the nets, which isn’t an insecticide itself, but it makes other insecticides more effective. Now it usually means adding a second insecticide to the nets, to create dual active ingredient (Dual AI) nets. The WHO now recommends using Dual AI nets containing pyrethroid and chlorfenapyr in areas with pyrethroid resistance. Unfortunately, these changes aren’t a complete solution for 3 reasons:

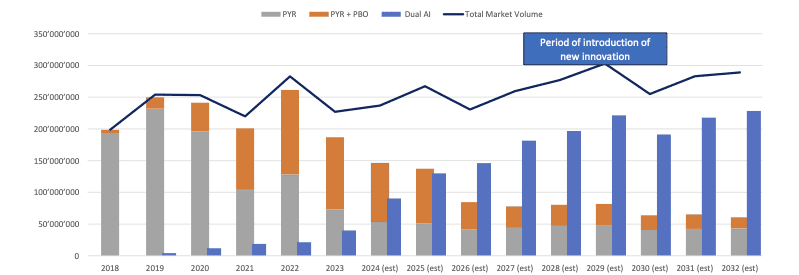

1. Pyrethroid-only bednets were the majority of nets distributed until 2021

Here is a graph from the IVCC showing the number of different types of bednets distributed from 2013-2024 (and projected distributions through 2032) Gray is pyrethroid-only nets, orange is pyrethroid plus PBO, and blue is Dual AI:

Going forward, everyone expected dual AI or pyrethroid+PBO nets to be the main type of bednets used. The Against Malaria Foundation’s latest purchase was entirely PBO or Dual AI nets, and they expect the same to true throughout 2025. But this is a recent change. Dual AI nets were a minor player until 2024. Pyrethroid+PBO nets only became a sizeable fraction of the total market in 2020 or 2021. So even if this problem is solved now, insecticide resistance would have been making bednets less effective through 2022.

2. These new nets cost more than pyrethroid-only nets

This is probably obvious, but the new nets cost more than the old nets. The rough costs I’ve found for the most commonly used sizes of nets are:

- Pyrethroid-only nets: $2.00 per net

- Pyrethroid+PBO: $2.50 – $2.70 per net

- Dual AI: $2.50 – $3.00 per net

Dual AI nets cost around 25 – 50% more than pyrethroid-only nets. I haven’t done a deep dive into all the costs of bednet distribution, but technical guidance from the President’s Malaria Initiative suggests these costs are $2–3 per net; meaning that responding to insecticide resistance has raised the overall costs of bednets by 15-25%. To put it another way, if dual AI or PBO nets are as effective at preventing malaria as pyrethroid-only nets were 20 years ago, then insecticide resistance has made bednets 15-25% less cost effective than they would be otherwise.

On the other hand, AMF says that bednets cost $5 in 2005, so dual AI nets now cost less than pyrethroid-only nets did 20 years ago.

3. PBO nets might be less effective now than pyrethroid-only nets used to be

The WHO has a (mostly) standardized protocol for performing small-scale field trials of bednet effectiveness, called experimental hut trials. These trials use specially designed huts where mosquitoes can enter but cannot leave. Human volunteers sleep in these huts for several weeks, and every morning researchers count the number of total mosquitoes, the number of dead mosquitoes, and the number of blood-fed mosquitoes in the huts. These trials compare the results of different insecticide-treated bednets to an untreated bednet as a control. The insecticide-treated nets are tested both straight out of the packaging and after being washed 20 times with soap and water, as a proxy for the effects of aging. All the nets have holes cut in them to mimic normal wear and tear.

The WHO recommends looking at two metrics for evaluating the results of an experimental hut trial:

- The percent personal protection, looking at the number of blood-fed mosquitoes in the huts with the treated nets compared to the control net.

- The percent killing effect, looking at the number of dead mosquitoes in the huts with the treated nets compared to the control net.

The two metrics correspond to the two modes of actions of insecticide-treated nets: preventing people from being bitten, and killing mosquitoes. For both metrics, higher numbers are better.

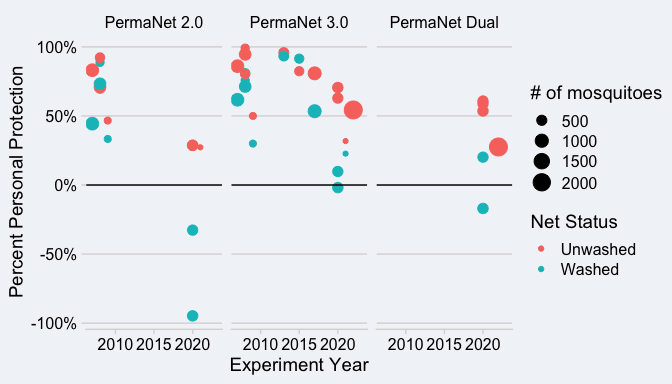

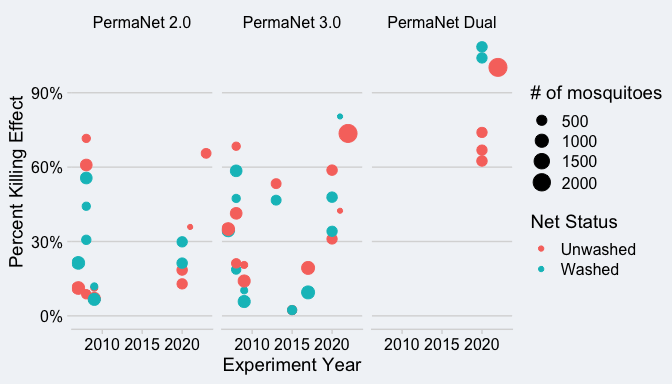

I was interested in seeing if experimental hut trials would show changing efficacy of different nets over time. To keep this project manageable, I focused on three different models of bednet made by Vestergaard:

- PermaNet 2.0, a pyrethroid-only net

- PermaNet 3.0, a pyrethroid + PBO net

- PermaNet Dual, a pyrethroid + chlorfenapyr net

I focused on the PermaNet over other types of nets because that also let me check whether these nets show a decline in efficacy after Vestergaard removed PFAS from the nets in 2012 (more about that later).

I did a very rough literature review, where I did a google scholar search for the terms “permanet 2.0 efficacy” and “permanet 3.0 efficacy”, read the first 4 pages of links, and kept any papers that involved experimental hut trials. I didn’t do a separate search for PermaNet Dual, so it’s possible that I’m missing some trials for that model.

Here are the results for personal protection:

And here are the results for the killing effect:

In each of these figures, the circles are sized by the total number of mosquitoes collected in the control huts and colored by whether the net was washed or unwashed. These experiments were all conducted in east or west Africa.

Looking at these graphs, it’s clear that in these areas, PermaNet 2.0s are now useless at personal protection (on average, they are worse than an untreated net), and have lost some of their effectiveness at killing mosquitoes as well. PermaNet 3.0s now have lower levels of personal protection than PermaNet 2.0s did before 2010, but they have remained equally effective at killing mosquitoes. This suggests that adding PBO to nets is at best a partial fix for insecticide resistance.

The PermaNet Dual is interesting, because it’s less effective at personal protection than the PermaNet 2.0 or 3.0 was before 2014, but is far more effective at killing mosquitoes than either other net ever was. That’s probably because the second insecticide in the PermaNet Dual, chlorfenapyr, works by disrupting the mosquito’s metabolism, so it takes more time to work than pyrethroids do. So these nets might not kill the mosquitoes fast enough to prevent them from biting people, but they would still kill the mosquitoes.

Because of how malaria works, this means than a dual AI net might not prevent mosquito to person malaria transmission, but it would prevent person to mosquito malaria transmission. I haven’t seen this written up anywhere, or worked through the details myself, but my guess is that this makes the PermaNet Dual less effective if you’re the only one using it (because there are plenty of mosquitoes with malaria that can infect you), but more effective if everyone in the community is using it (because it kills so many mosquitoes).

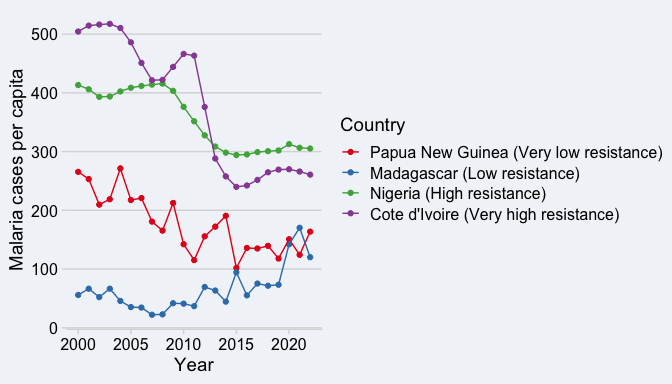

Counterpoint: The trend in malaria cases/pop in different countries doesn’t match the pattern in pyrethroid resistance

According to WHO estimates, malaria cases per capita declined in most countries in the world between 2003 and 2015, and then had basically stayed the same from 2015 to 2021. But the pattern in pyrethroid resistance shows a lot more variation between countries, in a way that doesn’t obviously show up in the malaria trends. As an example, I looked at 4 countries and eyeballed the level of pyrethroid resistance present in them based on the WHO malaria threat map:

- Papua New Guinea (almost no pyrethroid resistance)

- Madagascar (low levels of resistance)

- Nigeria (high levels of pyrethroid resistance, but at low intensity, meaning that higher concentrations are still effective)

- Cote d’Ivoire (high levels of resistance at high intensity)

But the trends in these four countries don’t behave in the ways you would expect if pyrethroid resistance was driving the trends:

Papua New Guinea, Cote d’Ivoire, and Nigeria all show a decrease until 2015 and constant levels since then. Madagascar actually has an increase in cases per capita since 2015. I haven’t done an in-depth statistical analysis, so maybe there’s something buried under a lot of noise, but I can’t see any relationship between the level or intensity of pyrethroid resistance and the trend in malaria cases since 2015.

I don’t think this is a total deal breaker for this theory. I think a more in-depth analysis would need to take into account how levels of pyrethroid resistance have changed over time, the levels of bednet coverage and how it has changed over time, and the specific model of nets used in different countries. This might be a case where our response to malaria and pyrethroid resistance might be masking any apparent relationship, because we’ll switch to different nets in areas where pyrethroid resistance is high but keep the old nets in areas where resistance is low but growing.

What are the relative contribution of these three components?

The responsible answer here would be to say “I’m not sure” and leave it at that. But that would be rather unsatisfying. So I performed a BOTEC just made some things up to estimate what the number of malaria cases would be in 2022 under different scenarios. My calculations are all in this spreadsheet. I looked at three different possibilities:

- Whether the population of sub-Saharan Africa in 2022 was 1,040 million (its actual population) or 860 million (its population in 2015)

- Whether the amount of funding spent combatting malaria was $4 billion (the real number) or $6.25 billion (what you’d get if funding had continued to grow at the rate it did from 2000 to 2010)

- Whether mosquitoes had developed resistance to pyrethroids or not

I also made some unreasonably simple assumptions to map these changes to changes in malaria cases:

- Malaria cases per capita stays constant as the population changes.

- Nets cost $2 without insecticide resistance and $2.25 with resistance.

- It takes $4 of additional funding to spend $1 on nets. This 4:1 ratio was chosen so that at current levels of funding, we see the approximately right level of net coverage.

- The relationship between number of nets per capita and the fraction of people who have access to nets is non-linear and follows the curve shown in Fig. 4 of Bertozzi-Villa et al., 2021.

- There is a linear relationship between the percent of people using bednets and malaria cases per capita. This is by far the most un-realistic assumption of the bunch, and it is absolutely wrong. I tried using a more realistic relationship based on the Cochrane Review results or the Chitnis model, but I couldn’t get the the results to match the change in malaria cases per capita we saw from 2005 to 2015. I think for a more realistic model to work you’d have to include spatial variability in net usage.

- For every 1 percentage point increase in bednet usage rate, malaria cases decrease by 2.16 cases per thousand people. The slope is based on the correlation between bednet usage rate and malaria cases per capita in sub-Saharan Africa from 2005 to 2022.

- If there wasn’t any insecticide resistance, this slope would be 33% larger. That’s a very crude estimate based on the results for the experimental hut trials.

Those assumptions let us translate the changes in population, funding, and insecticide resistance into changes in overall malaria cases. Here’s what I get for two scenarios:

| Scenario | Annual Malaria Cases (millions) |

|---|---|

| Continued population growth, no funding growth, insecticide resistance (reality) | 232 |

| Continued funding growth, no population growth, no insecticide resistance | 102 |

I then used Shapley values to attribute what fraction of the hypothetical decrease in cases is attributable to each of the three factors:

| Factor | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Population growth | 34% |

| No funding growth | 27% |

| Insecticide Resistance | 39% |

Given how crude my estimate is, the most I’d feel comfortable saying is that all three factors are roughly equally important. I’m honestly surprised how large a factor insecticide resistance is — partway through this project my working hypothesis was that population and funding explained everything, but that turned out to be wrong.

Factors that don’t seem to be major contributors

As is perhaps inevitable, there were a number of theories that I initially considered or thought were important, but upon further reflection have concluded aren’t major factors in explaining the global trend in malaria case rates.

The decline until 2015 and stagnation after do not represent trends in separate countries or regions

You could imagine a scenario where malaria control efforts were always very successful in some countries and ineffective in others. That could lead to a global decline in cases as we make progress in the successful countries, but once malaria was solved in those countries, no further declines would occur.

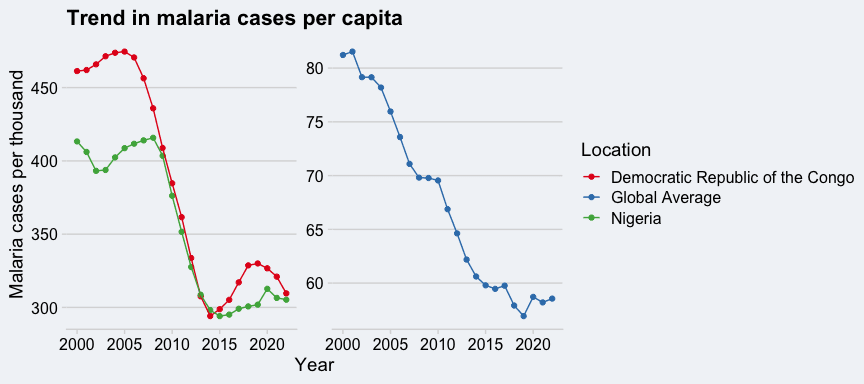

At least based on WHO data, that does not appear to be the case. The two countries that currently have the highest number of malaria cases, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, also saw a large decline in cases per capita between 2000 and 2015:

In fact most countries show this same pattern of a decline 2000–2015 followed by stagnation. This pretty conclusively rules out the hypothesis that bednets or other malaria control efforts worked in some countries but not in other.

Removing PFAS from bednets doesn’t appear to have affected experimental hut results

Before we get into the controversy here, let’s lay out some background information. The WHO lays out 4 different ways of testing the efficacy of bednets, ranging from small scale lab tests to large scale field trials:

- Cone tests: mosquitoes are exposed to a bednet for a few minutes, and then transferred to a box. Count how many mosquitoes are unable to fly (“knocked down”) after 60 minutes and how many are dead after 24 hours.

- Tunnel tests: Put mosquitoes into one side of a chamber, put a rabbit or guinea pig on in the other side of the chamber, and put a bednet in between them. After 12-15 hours, count how many mosquitoes successfully blood-fed from the animal and how many mosquitoes died.

- Experimental hut trials: These are the simplest level of field trials for bednets. The idea is to measure the efficacy of bednets under fairly realistic conditions using specially designed huts where mosquitoes can enter but cannot leave. Have human volunteers sleep in these huts for several weeks, and every morning count the number of total mosquitoes, the number of dead mosquitoes, and the number of blood-fed mosquitoes. Compare the results between different LLINs and an untreated bednet as a control.

- Large scale field trials: Under WHO protocol, the purpose of these tests is to measure the durability of both the net fabric and the insecticide under real-world conditions, not to measure how effective they are at preventing malaria.

Among these tests, cone tests and tunnel tests take days and are performed in a laboratory. Experimental hut trials require specially constructed buildings and require weeks of measurement. Large scale field trials take years. WHO wants to see field trials and RCTs before recommending the use of new classes of bednets, but they certify new models of bednets based on the results of either cone tests or tunnel tests.

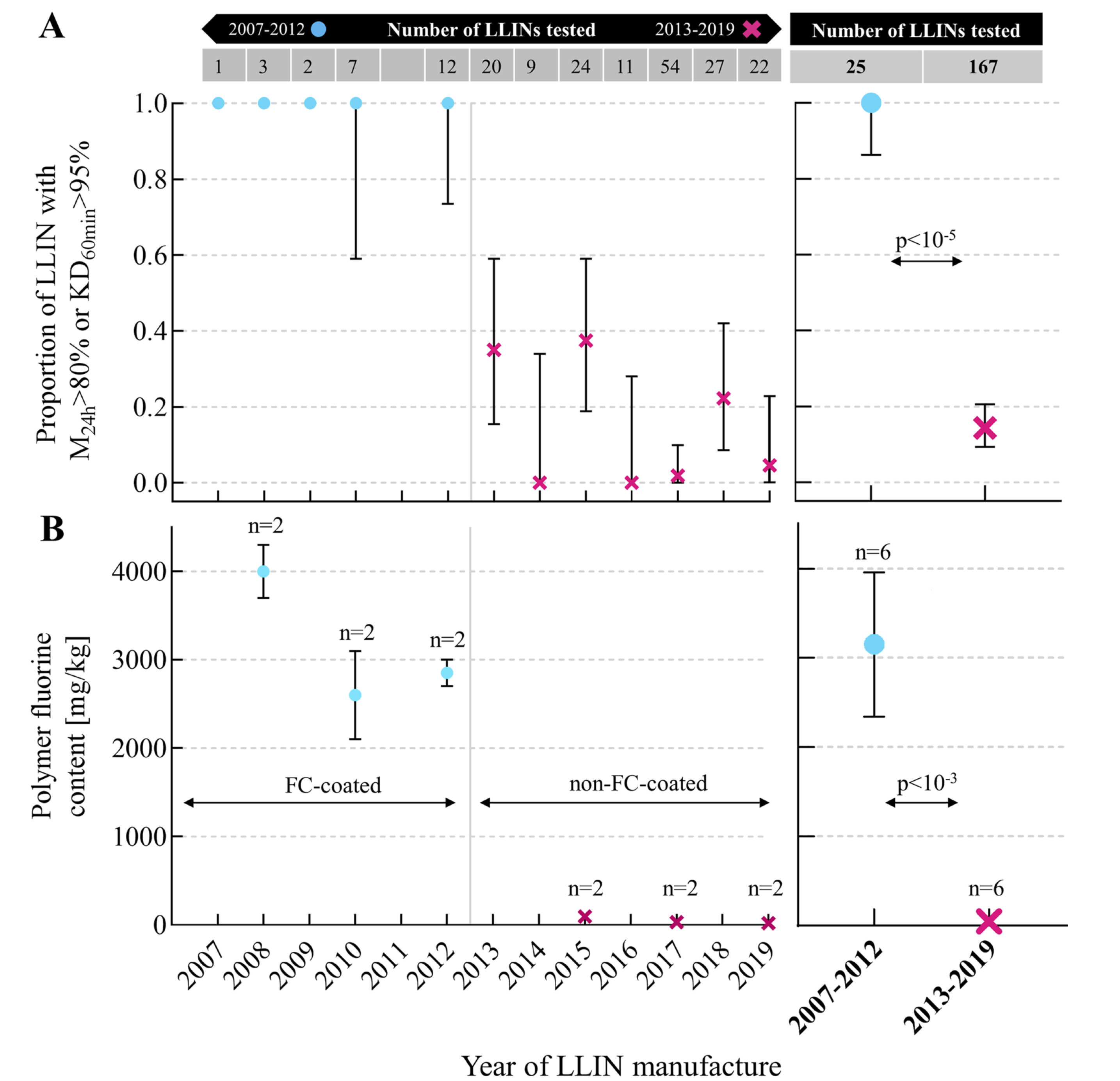

With that background, let’s talk about the PFAS elephant in the room. There is a study from Papua New Guinea (and an associated write-up in Bloomberg) showing that versions of the Vestergaard PermaNet 2.0 made after 2012 are much less effective at killing mosquitoes in cone tests than the same model of net made before 2012. The results from this study are not subtle:

The researchers attribute this to a decision made by Vestergaard in 2012 to remove PFAS from the coating that binds the insecticide to the nets. Vestergaard says that their nets have always met WHO efficacy requirements and actually when other people do these tests, PermaNet 2.0s are still effective in cone tests. After looking into this, I have many thoughts:

- I am convinced by the studies from the Papua New Guinea team that versions of the PermaNet 2.0 made after 2012 are less effective at killing mosquitoes in cone tests. However, I haven’t seen evidence that a reduction in efficacy in cone tests translates to reduced effectiveness in the field.

- The timing is certainly suggestive. A manufacturing change in 2012 plus a 3-year lifespan for a bednet would mean the last of the pre-2012 nets would be replaced in 2015, right when the malaria case rate stopped declining.

- I am frustrated that I’ve been able to find so little discussion/analysis of these results from any other groups. The WHO World Malaria Report 2023 and 2024 don’t seem to mention it. I haven’t been able to find anything about it from AMF

or from GiveWell. I get the sense that these groups don’t think that it’s a big deal, but I wish they would explain why. [Edit: GiveWell said a year ago that "we see this as a milder negative update on nets than the article would indicate, in part because we think these tests of net quality may not be a perfect proxy for effectiveness in reducing cases and in part because we no longer fund PermaNet 2.0s (for unrelated reasons)".] - The results from the experimental hut trials that I found don’t show a sudden change in net efficacy after 2012. I don’t have a good timeseries of results for the PermaNet 2.0, but I believe the PermaNet 3.0 also had its coating changed at the same time as the PermaNet 2.0. It shows a much higher personal protection effect than the PermaNet 2.0 and a slow decline in effectiveness from 2013 – 2022, rather than the step change after 2012 suggested by the Papua New Guinea study.

Given the results of the experimental hut trials, I don’t think removing PFAS had a major impact on the overall efficacy of bednets

Anopheles stephensi isn’t present in the areas with the highest rates of malaria yet

The spread of Anopheles stephensi mosquitos from India to Africa is another threat to malaria control that’s broken into the mainstream press. Unlike other mosquitos that spread malaria in Africa, An. stephensi thrives during the dry season and in urban areas, and it’s already causing unusual malaria outbreaks in Ethiopia. Oh, and it’s also resistance to pyrethroids.

While this is bad news for the future, I don’t think it can explain the rise in malaria cases between 2015 and 2022. So far, this species of mosquito is mostly present in the horn of Africa, and has not been consistently detected in West Africa. There have been a few detected in Ghana and Nigeria, but most of the tests done in Nigeria in the past few years haven’t found any An. stephensi mosquitoes. Given the limited spread so far, I think Anopheles stephensi is a problem for future malaria control, but not a major factor so far.

Nobody knows if climate change is making malaria worse

This one was surprising to me, given that Al Gore taught me that climate changes was going to cause malaria to spread like wildfire. But while malaria is a tropical disease and so you might assume that warmer temperatures means more malaria, reality is more complicated. Malaria transmission is highly dependent on both temperature and rainfall, and the effect of climate change on rainfall is much more varied than its effect on temperature. Add in possible changes in human behavior in response to climate change (e.g., do warmer temperature cause us to be outdoor more in the evenings, when mosquitoes are most active?), and you can see why the effect of climate change on malaria is unknown. Quoting the WHO World Malaria Report 2023:

Views on how climate change affects malaria transmission are diverse – some experts suggest it may cause a major malaria expansion, whereas others suggest that the direct effect on malaria transmission will be marginal, especially in the face of changes in other co-determinants. Regardless of the diverse views, there is a consensus that climate change and its interaction with malaria transmission is complex and that empirical evidence to support reliable predictions is sparse. Also, the direction and magnitude of long-term effects of climate change on malaria transmission and burden are likely to vary across social and ecological systems, both within and between countries.

WHO World Malaria Report 2023, p94

While this says that climate change could either have no effect on malaria or a big increase, I think we should read this statement in light of WHO’s normal position that climate change makes everything worse and conclude that nobody knows what effect climate change will have on malaria.

Conclusions

- The increase in malaria cases from 2015 to 2022 was likely caused in roughly equal measure by population growth, stagnant funding, and insecticide resistance.

- I didn’t find any evidence for the idea that bednets have completely stopped being effective (due to insecticide resistance, manufacturing changes, or country-specific factors)

- However, bednets in 2024 were probably less effective than they were in 2005, due to insecticide resistance. But that’s not the same thing as not effective. Pyrethroid+PBO bednets were still effective at personal protection, and even pyrethroid-only bednets in high-resistance areas still killed an appreciable fraction of mosquitoes

- The newest model of bednets, pyrethroid+chlorfenapyr bednets, have the potential to be more cost-effective than any previous model of bednets, because they are so much better at killing mosquitoes.

- Bednets are great. Have you considered donating to buy bednets?

- ^

Deaths from malaria are still way below where they were in 2000, although they have also increased since 2019. WHO estimates that there were 860,000 deaths due to malaria in 2000, 576,000 in 2019, and 608,000 in 2022.

- ^

Technically these all are different categories. LLINs refer specifically to nets where the insecticide is incorporated into the net itself. ITNs also include bednets that have to be periodically dipped in insecticide. Bednets can also refer to nets without any insecticide. In practice almost all of the nets used for the past 15 years are LLINs so I’m going to use the terms LLIN, ITN, and bednet interchangeably and use the term “untreated net” if I need to refer to a net without insecticide.

- ^

If you’re wondering why the fraction of people infected is so much lower for the Chitnis model, it’s because it’s the only model that includes post-infection immunity to malaria.

Given that the prevalence has reduced since 2015, I don't think that makes sense.