Following Ord (2023) I define the total value of the future as

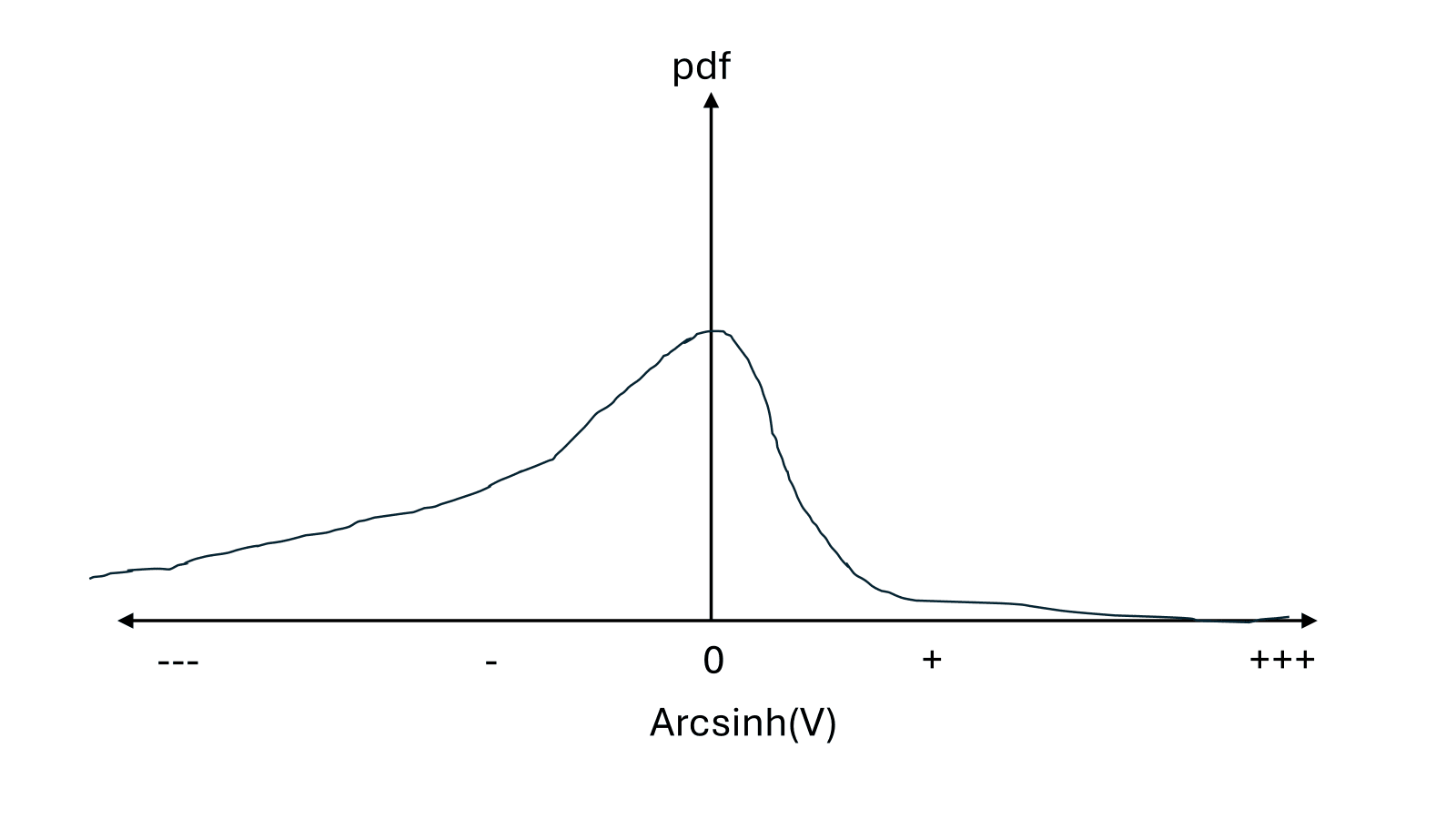

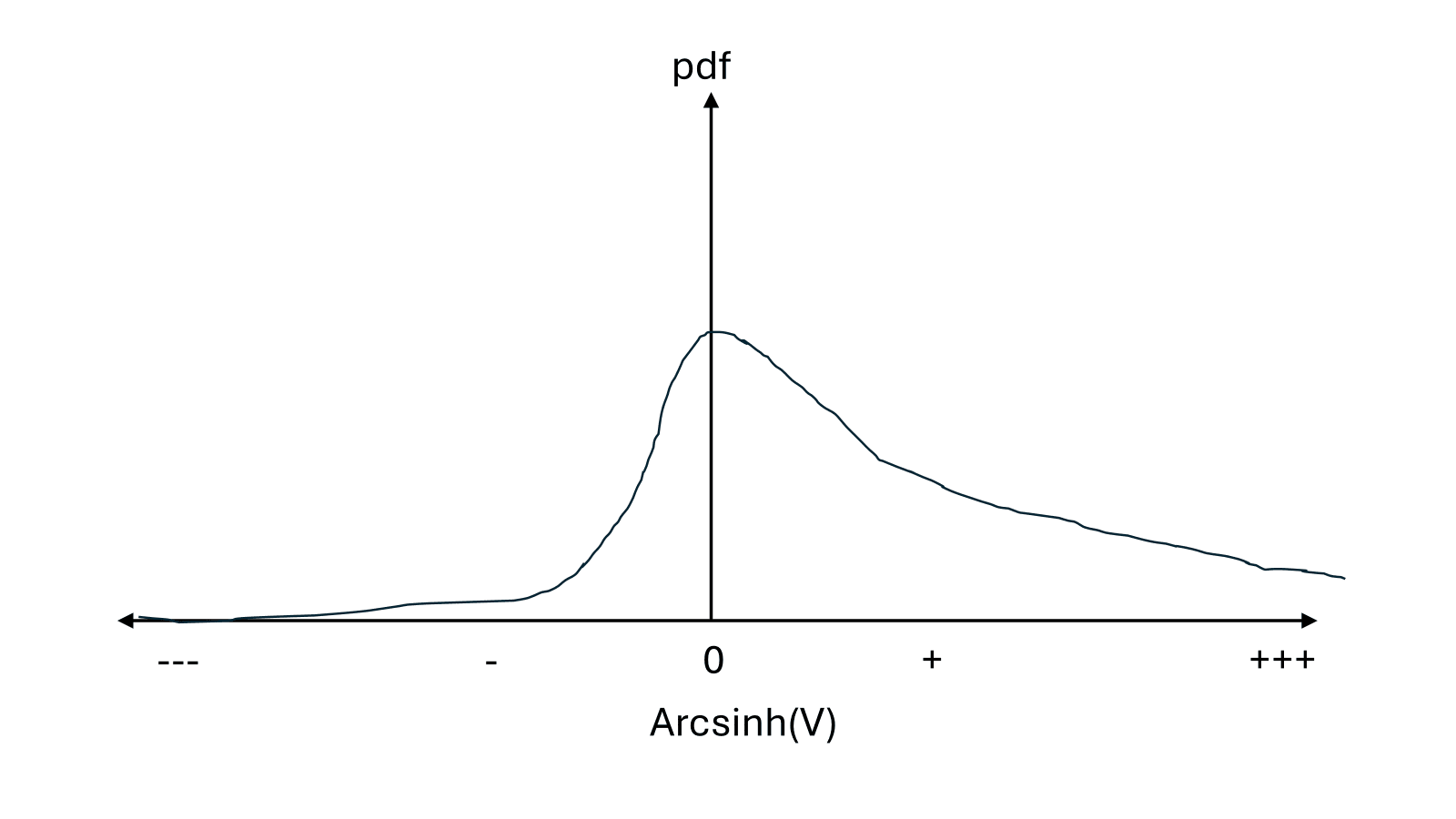

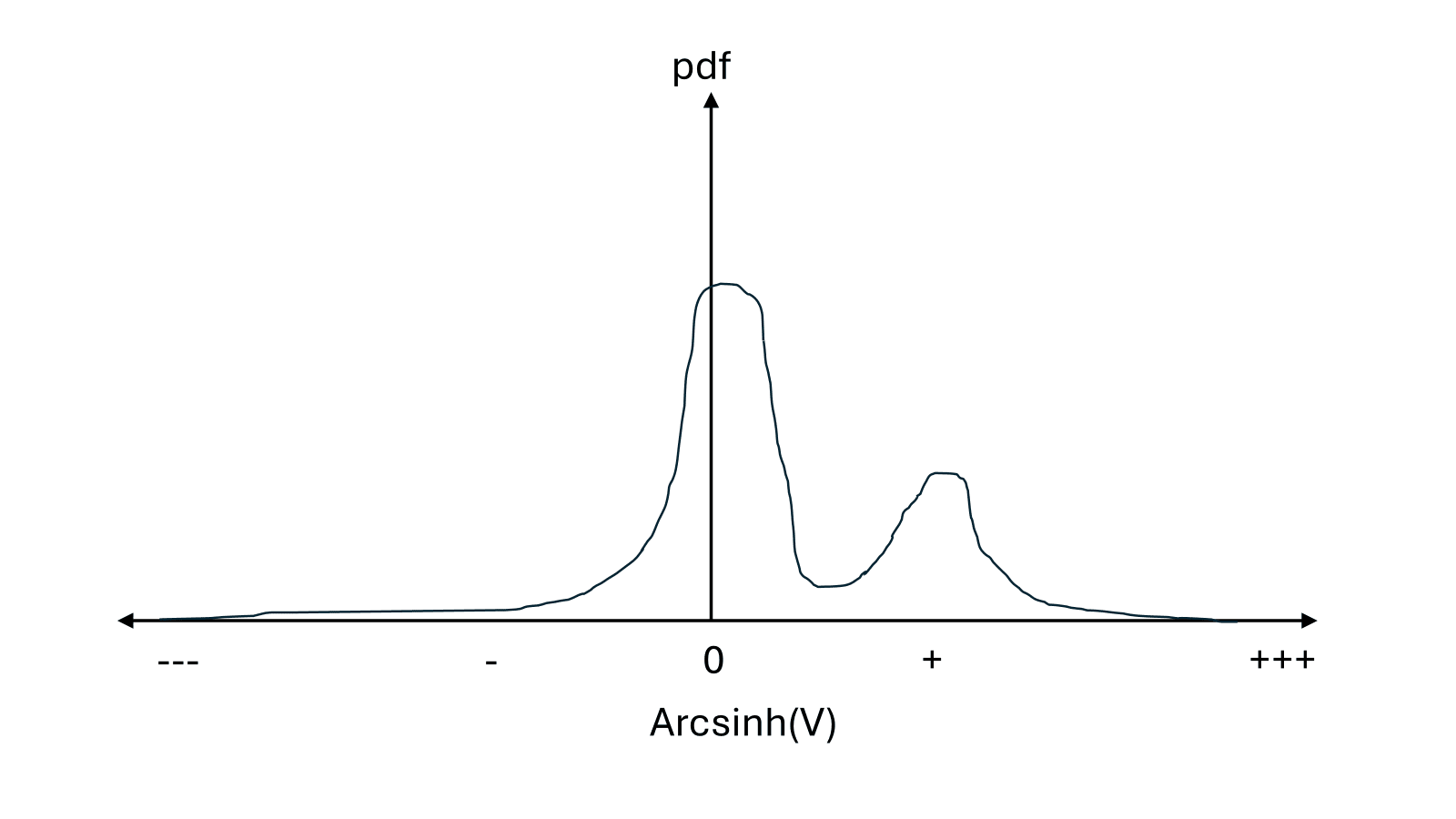

where is the length of time until extinction and is the instantaneous value of the world at time . Of course, we are uncertain what value V will take, so we should consider a probability distribution of possible values of V.[1] On the y-axis in the following graphs is probability density, and on the x-axis is a pseudo-log transformed version of V that allows V to vary by sign and over many OOMs on the same axis.[2]

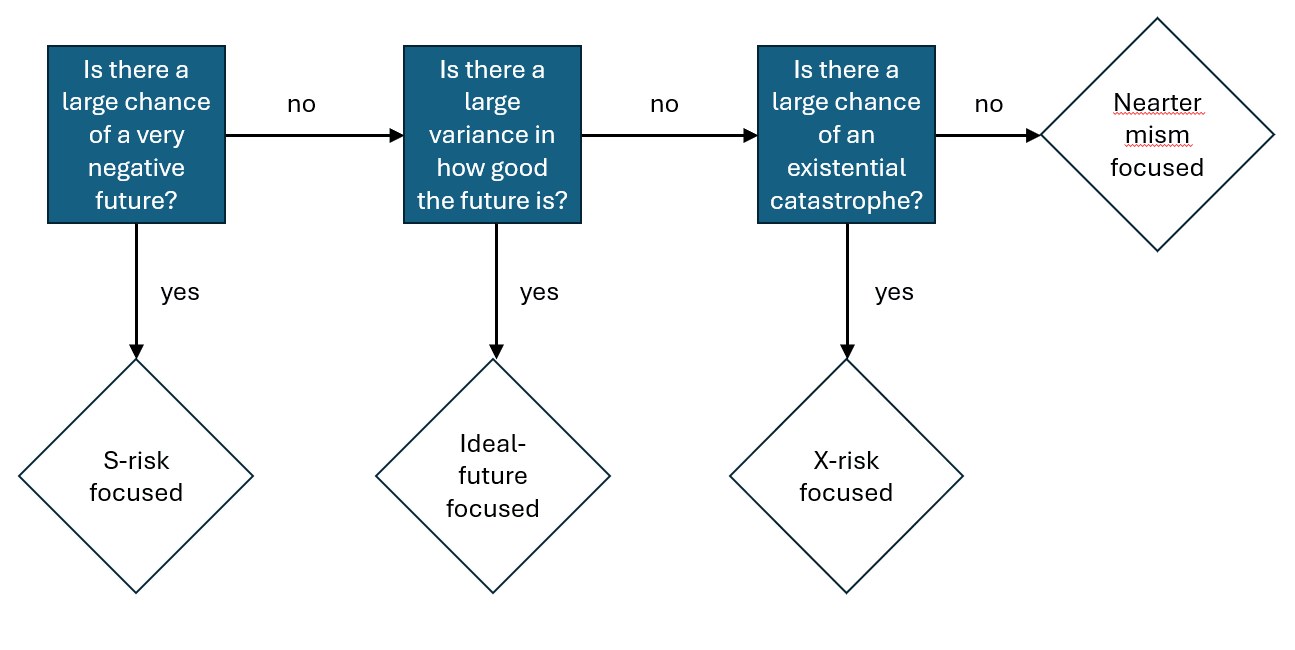

There are infinite possible distributions we may believe, but we can tease out some important distinguishing features of distributions of V, and map these onto plausible longtermist prioritisations of how to improve the future.

S-risk focused

If there is a significant chance of very bad futures (S-risks), then making those futures either less likely to occur, or less bad if they do occur seems very valuable, regardless of the relative probability of extinction versus nice futures.

Ideal-future focused

If bad futures are very unlikely, and there is a very high variance in just how good positive futures are, then moving probability mass from moderately good to astronomically good futures could be even more valuable than moving probability mass from extinction to moderately good futures (keeping in mind the log-like transformation of the x-axis).

X-risk focused

If there is a large probability of both near-term extinction and a good future, but both astronomically good and astronomically bad futures are ~impossible, then preventing X-risks (and thereby locking us into one of many possible low-variance moderately good futures) seems very important.

Discussion

- Some differences between these camps are normative, e.g. negative utilitarians are more likely to focus on S-risks, and person-affecting views are more likely to favour X-risk prevention over ensuring good futures are astronomically large. But significant prioritisation disagreement probably also arises from empirical disagreements about likely future trajectories, as stylistically represented by my three probability distributions. In flowchart form this is something like:

- I have not encountered particularly strong arguments about what sort of distribution we should assign to V - my impression is that intuitions (implicit Bayesian priors) are doing a lot of the work, and it may be quite hard to change someone’s mind about the shape of this distribution. But I think explicitly describing and drawing these distributions can be useful in at least understanding our empirical disagreements.

- I don’t have any particular conclusions, I just found this a helpful framing/visualisation for my thinking and maybe it will be for others too.

I don't think that high x-risk implies that we should focus more on x-risk all else equal - high x-risk means that the value of the future is lower. I think what we should care about is high tractability of x-risk, which sometimes but doesn't necessarily correspond to a high probability of x-risk.

I think high X-risk makes working on X-risk more valuable only if you believe that you can have a durable effect on the level of X-risk - here's MacAskill talking about the hinge-of-history hypothesis (which is closely related to the 'time of perils' hypothesis):