Hey Team,

Since publishing an article on the Liberation Pledge with the Journal for Critical Animal Studies last February, i've repeatedly been encouraged to share the article to the EA Forum. So here it goes:

The Liberation Pledge entails a commitment to never eat alongside people consuming animal-based foods. In the article, i argue that the Liberation Pledge is an exceptionally effective tactic for individuals to challenge the diverse harms of Big Meat. Relatedly, i also argue that individual veganism absent the Liberation Pledge does little to affect change, and in some cases is counterproductive.

Like my article, i'll spare you the justification for why curbing the harms of Big Meat is urgent and important (as i suspect most on the EA Forum are already familiar). From that assumed starting point, i invite readers to share feedback regarding the merits of the Liberation Pledge, and the argument i lay out to defend it. Copied below is the complete text (you can find the PDF here).

My hope is that the article clarifies the value of veganism to movements (human, nonhuman, and environmental) to end Big Meat, and encourages readers to take the Liberation Pledge themself. Given effective altruists' active work to live more in line with our values, i hope the Pledge will soon become common amongst the community.

PS: If you are interested in exploring the idea on different mediums (or in fewer words), you can view the following:

- Podcast interview: Our Hen House

- Op-ed: Sentient Media

- Webinar: Vegan World 2026

- Entrevista en Español: La Quinta Pata

Silence Abets Violence: The Case for the Liberation Pledge

Abstract: Animal agriculture brutalizes hundreds of billions of animals every year. More and more, veganism has been promoted as a way for individuals to address this violence. However, when passively pursued via personal dietary divestment, a vegan ethic fails to substantively challenge the cultural hegemony of carnism—the ideology that justifies the consumption of certain animals. Rather, in tacitly accepting the carnism of others, passive vegan eaters normalize and perpetuate the very exploitation their ethic stands against. The Liberation Pledge—essentially a commitment to never eat around those consuming animal products—is a response to this understanding. By explicitly and emphatically condemning the dietary violence of others, the Liberation Pledge functions to actively de-normalize the oppressive system, eroding a central tenant upon which carnism persists. Centrally, in this paper I contend that the Liberation Pledge is one of the most effective tools for doing so. It is my hope that readers will leave convinced to uptake the Pledge themselves, and if not, that the seeds for such action have been planted and await germination.

“The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything.”

—Albert Einstein[1]

Animal agriculture brutalizes hundreds of billions of animals every year. More and more, veganism is promoted as a way for individuals to address this violence. However, when passively pursued via personal dietary divestment, a vegan ethic fails to substantively challenge the cultural hegemony of carnism—the ideology that justifies the consumption of certain animals. Rather, in tacitly accepting the carnism of others, passive vegan eaters normalize and perpetuate the very exploitation their ethic stands against. The Liberation Pledge—essentially a commitment to never eat around those consuming animal products—is a response to this understanding. By explicitly and emphatically condemning the dietary violence of others, the Liberation Pledge functions to actively de-normalize the oppressive system, eroding a central tenant upon which it persists. The Liberation Pledge is one of the most effective tools for doing so at the individual level.

In line with critical animal studies’ foundational call for linking “theory to practice” the Liberation Pledge advocates the same.[2] It is the practice of the Liberation Pledge—not merely passive veganism—that constitutes enactment of an animal liberation ethic. That is, the Liberation Pledge turns the theory underlying ethical veganism into its logical conclusion in praxis.

Accepting this argument should lead towards reconceptualizing veganism’s role in the animal liberation movement. This article focuses on the individualized application of this conclusion, namely practicing the Liberation Pledge oneself and urging others to follow suit. However, albeit not the focus here, the same lesson applies institutionally, an application that calls for shifting resources and messaging away from encouraging negative duties (e.g., personal dietary change) and towards advocating positive duties to promote animal liberation.

What follows, then, is essentially an argument for animal liberationists to evolve their activism by adopting the Liberation Pledge. Section I begins with an overview of the Liberation Pledge. Section II explains the Pledge’s theory of change. Section III highlights the Liberation Pledge’s historic impact and its potential for growth. And section IV responds to seven central critiques. Having thus made the case for the efficacy of the Liberation Pledge, Section V concludes by arguing for the adoption of the Liberation Pledge (or similar activism) as a moral imperative.

Despite being the first academic article to address this topic, I hope it will not be the last. Rather, given my belief in the power and relevance of the Liberation Pledge, I hope this article opens space for continued academic dialogue to follow. For not only is this topic rich with research potential—from qualitative research regarding the experiences of Pledge practitioners to theoretical work exploring its institutional applications—but more importantly, such research has the power to affect positive change.

I. The Liberation Pledge

“For to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

—Nelson Mandela[3]

The idea for the Liberation Pledge came out of conversations between activists in the San Francisco Bay Area. Frustrated with the historic trajectory of the animal liberation movement and concerned about its capacity for success moving forward, these activists concluded that neither passive veganism nor the movement’s focus on promulgating it were effective strategies. Instead, they reasoned hegemonic social norms would not change—especially not at the rate they need to—absent direct confrontation and pressure. Given this conclusion, the Liberation Pledge was developed as a way to address passive veganism’s failure to do so.

Since its inauguration in 2015, the Liberation Pledge has historically consisted of three parts: one, publicly refuse to eat animals; two, publicly refuse to sit where animals are being eaten; and three, encourage others to take the Pledge.[4] Ideally, the Pledge is a lifelong commitment. While this original version of the Liberation Pledge is not meant to condone any form of animal exploitation, its focus has typically targeted the consumption of animal flesh. Its stated purpose for doing so is to avoid slipping into interrogations regarding the ambiguous veganity of products like bagels, sugar, etc. That said, my interpretation and support of the Liberation Pledge argues for adhering to it whenever another is consuming a product of known animal origin.

Given the Pledge’s focus on dismantling carnism—the ideology that normalizes the edibility of certain animals—it is focused exclusively on boycotting dietary violence. In not applying to other forms of violence done to animals—including clothing production, scientific research, “pet” breeding, and entertainment—the Pledge does not connote tolerance of these industries. Indeed, the ethos underlying many practitioners’ commitment to the Pledge rejects the (ab)use of animals for any purpose. That said, while the Liberation Pledge is specifically designed to dismantle the violence bound up within carnism (the topic of Section II), it can be freely practiced alongside any other liberatory strategies.

In considering nuances to the Liberation Pledge, Torres outlines and endorses three levels it can take.[5] The most basic level accords with the Pledge’s original framing, and entails abstaining from eating at any non-vegetarian table—i.e., refusing to dine around anyone consuming animal flesh. Torres argues that while this version does condone the consumption of animal products like milk and eggs, it still gets the point across but in a way that can “be touted as a ‘compromise.’” To be clear, I do not endorse this version of the Pledge. As will be argued in Section II, a central power of the Pledge comes from its moral rejection of animal products as edible, and this version patently fails to do so. As a result, I believe this version muddies what should be a clear and coherent position—that animals are not ours to use—to the detriment of the animal liberation movement. We should not make compromises around “tolerable” forms of violence, and the fact that this level does so should be perceived not as beneficial but as disqualifying.

The second level Torres discusses entails abstaining from eating at what he calls “tables of violence”—i.e., refusing to sit at a table where animal flesh and/or animal products are present. At this level practitioners are free to attend restaurants or events that serve animal products, even though doing so might necessitate sitting at a different table or in a different room when it is time to eat. The third level entails abstaining from eating in “places of violence”—i.e., refusing to go to any restaurant or event that profits directly from exploiting animals as food. This is the most challenging level, though it is made easier for individuals who have access to vegan-friendly venues and to those who have plant-based or open-minded family members.

While I myself practice the second level, I equally support the third as well, as both in my view are strategic and morally justifiable, albeit with their own strengths. For example, whereas the second level serves to open the range of events available to the practitioner (and thus their range of influence) without compromising the Pledge’s message, the latter powerfully clarifies that it is morally reprehensible for institutions to profit from animal exploitation irrespective of the practitioner or their cohort’s direct complicity in those profits. Consequently, while rejecting the first level, I do not advocate for adopting the second or third level. Instead, I encourage others to follow whichever option resonates, and do not distinguish between the two again in this article.

While not required, practitioners of the Liberation Pledge are encouraged to adopt the Liberation Band, a fork bent into a bracelet. The symbology of the Band is both informative and inspiring. From the Book of Isaiah comes the passage: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks.”[6] “Swords to plowshares” is a concept wherein destructive military weapons, implements of violence, are converted into peaceful tools meant to benefit society. The concept is prominently embodied and enacted by the Plowshares movement, a Christian pacifist and anti-nuclear weapons movement that advocates active resistance to war.[7]

As Gandhi is often claimed to have said, the fork arguably represents the most violent implement in society today.[8] An estimated 70 billion—70,000,000,000—terrestrial animals are slaughtered in animal agriculture alongside well over a trillion—1,000,000,000,000—hunted or farmed aquatic animals every year.[9] To put this aggregate number into perspective, only 108 billion humans are estimated to have ever been born, meaning we kill an order of magnitude more animals each year to eat than the number of humans who have ever existed.[10] As such, like turning swords to plowshares, the Liberation Band seeks to transform the fork from its symbol of violence into a symbol of active resistance.

While motivating, the real value of this symbology comes from its utility in empowering the practitioner to affect social change. First, the band is unique and striking, features that enable it to be employed to fulfill the Liberation Pledge’s third goal of encouraging others adopt the Pledge. A stranger’s offhanded comment—“cool bracelet”—can easily be responded to with an explanation regarding its purpose and significance; moreover, such outreach is often made more effective by others initiating the conversation, as the activist’s ensuing explanation seems warranted. Second, the band helps to show solidarity and build community with other individuals who have taken the Pledge. Practicing the Pledge can at times be isolating; as such, being able to identify others who have made the same commitment affirms the unity and community of practitioners. Third, in the rote daily actions of washing hands, getting (un)dressed, etc., the Liberation Band serves as a constant reminder to the activist of their values and commitment to them. Humans evolved to react to harms that we experience directly, not abstract harms we have read about.[11] As such, the Liberation Band serves as a way to help regularly remind ourselves of the omnipresent “war against animals” that demands our active resistance.[12]

It is primarily for these three pragmatic advantages that activists are encouraged to don the Liberation Band while in public. However, despite this suggestion, practitioners are free to decline wearing the Band if they so prefer. For as the subsequent sections will make clear, the true power of the Liberation Pledge comes from the interpersonal interactions it facilitates and the psychological benefits that stem from them.

II. Liberation Pledge Theory of Change

“Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul”

—Edward Abbey[13]

Like veganism, the Liberation Pledge should not be understood as a privileged bourgeois personal choice that makes practitioners feel better.[14] While it can bring tremendous peace and clarity to the practitioner’s life and relationships, these benefits are incidental. Rather, the Liberation Pledge should be understood as a political tool, one of many, used by activists in working towards “total liberation."[15] At its core, the central power of the Liberation Pledge lies in its ability to actively challenge the “normalcy” with which we exploit animals for food. By refusing to accept such violence as normal, practitioners of the Liberation Pledge sow the seeds for constructing new social norms and ontologies free from human supremacy.

As first explained by Joy, carnism is the ideology that conditions humans to accept the consumption of certain animals as normal and acceptable.[16] Carnism can be understood as essentially the opposite of veganism; whereas a vegan ethic derides the exploitation of animals for food, carnism accepts the violence embedded within the consumption of animal flesh, secretions, and other products. Throughout this article, I essentially use the term to stand in for “non-vegan,” as doing so serves to mark carnism as an abnormal system and leave veganism as unmarked;[17] this reframing—of veganism from marked to unmarked—is essentially what the Liberation Pledge does in practice.

Joy explains that the construction of carnism is built upon and justified by what she names the 3Ns—normal, natural, and necessary.[18] In essence, the justifications for exploiting animals as “food” can be boiled down to these 3 Ns. And as such, these frameworks are essentially what enable carnism to persist. However, it is not inherently normal, natural, or necessary to eat animals; on the contrary, carnism is a social construction that has been normalized and systemized over time. As Chiles and Fitzgerald explain:[19]

Except under conditions of environmental scarcity, the meaning and value of meat cannot be attributed to intrinsic biophysical value or to the political-economic actors who materially benefit from it. Rather, meat’s status reflects the myriad cultural contexts in which it is socially constructed in people’s everyday lives, particularly with respect to religious, gender, communal, racial, national, and class identity.

By historicizing the apparent naturalness and normalcy of animal consumption—particularly through their demonstration that the political-economic, biophysical, and cultural contexts around meat eating have changed—Chiles and Fitzgerald show that the legitimacy of carnism is not material. Rather, in doing so they elucidate the role that culture has played in the legitimation of meat, an understanding that opens space for the construction of a novel framing of what is and is not normal and acceptable to eat. That is, because carnism is not “natural,” per se, but has instead been socially constructed, so too can it be deconstructed.

Given this context, the Liberation Pledge’s primary value comes from its ability to effectively challenge the normalcy with which we consume other beings. In particular, it does so through enacting and reifying what I refer to as “vegan consciousness,” a framework I adapt from Sandra Bartky’s notion of “feminist consciousness.” Bartky highlights that it’s not that feminists are aware of different things than other people, but that “they are aware of the same things differently. Feminist consciousness, it might be ventured, turns a ‘fact’ into a ‘contradiction’” (p. 22).[20] Similarly, vegan consciousness sees the world in very different terms than does carnist consciousness. Those who take the Liberation Pledge do so out of their understanding that it is not inherently normal nor acceptable to consume the flesh or products of sentient nonhumans. Nor should doing so be perceived as a morally-neutral personal choice. Rather, practitioners understand acts of carnism as acts of violence, and actively condemn and challenge them as such.

In enacting “vegan consciousness,” the Liberation Pledge primarily operates by targeting two factors foundational to the construction of carnism: one, the perceived edibility of animals, and two, their invisibility as victims.

With regard to the former, the practitioner explicitly refuses to morally accept the edibility of sentient animals or their products. Unfortunately, the zeitgeist conceptualizes both as edible. To demonstrate why that is problematic, it is useful to consider the human parallel. As a society we staunchly reject and stigmatize human edibility as immoral. For imagine how our interactions with other humans would be impacted if that wasn’t the case, if we came to see humans, even just some humans, as edible.[21] Doing so would fundamentally shift our relationships and the value we give them. It would frame ourselves and others as consumable—as useable—and fundamentally compromise our capacity to respect and relate to one another as free beings.

The same consequences apply to nonhuman animals. Accepting animals and their products as edible ontologically positions them as (ab)useable, a framing that precludes them from being fully incorporated into our moral circle. Consequently, expanding our moral circle to include all sentient animals requires us to see them as inedible. So in the same way most would never entertain eating humans killed unintentionally (e.g., being struck by lightning or hit by a car), we should likewise never entertain the consumption of animals, irrespective of whether or not our consumption fuels future economic demand for their “production” (e.g., flesh qua “roadkill” or “trash”). The Liberation Pledge acknowledges this reality by refusing to condone or tolerate the labeling of any sentient individual as food and challenges others to make the same connection.

Instead, directly challenging the notion of animal edibility functions to cut through problematic distractions and present a clear and coherent message. In practicing the Liberation Pledge, the practitioner rejects any superfluous label such as “humane” or “cage-free” as immaterial. Rather, their actions are informed by the understanding that such considerations are morally compromised from the outset, as they tacitly accept both the legitimacy of animal use as well as the notion that others have the right to its violent products. Instead, by unconditionally challenging the edibility of animals, the practitioner focuses the conversation on what matters: the bottom line that animals are not ours to use.

With regard to the second factor—carnism’s dependence upon hiding its victims—the Liberation Pledge responds by refusing to allow what Adams calls the absent referent to remain absent:[22]

Behind every meal of meat is an absence: the death of the animal whose place the meat takes. The “absent referent” is that which separates the meat eater from the animal and the animal from the end product. The function of the absent referent is to keep our “meat” separated from any idea that she or he was once an animal, to keep the “moo” or “cluck” or “baa” away from the meat, to keep something from being seen as having been someone.

By erasing the victim, the absent referent serves to enable well-intentioned individuals to more easily accept the normalization of carnism. In fact, nearly two dozen scientific studies have found such cognitive dissociation to be one of the most common and important psychological factors for doing so.[23]

Acknowledging this, practitioners of the Liberation Pledge refuse to tacitly allow those they are around to erase the individuality of the persons whose flesh and products they are consuming. Instead, the practitioner makes it clear that they will not condone such actions, and centrally, that their activism is motivated by the individuals who suffered to produce the meal others are eating. Doing so not only forces others to think critically about who they are eating, but emphatically de-normalizes the practice in the process.

While the Liberation Pledge’s theoretical motivations are foundational, their true power comes from the manner in which they are enacted. Most importantly, by taking the Liberation Pledge, practitioners transform their resistance to carnism from passive to active, from an ideology to an applied practice–that is, to praxis. Some may argue that veganism already does so effectively, pointing in part to the economic impact affected by boycotting carnist products in favor of vegan alternatives. But while doing so may in fact decrease demand for carnist products and increase demand for vegan products, given the vanishingly small percentage of vegans today the systemic economic impact of this is unfortunately marginal at best.[24]

Instead, given carnism’s cultural construction, a practice’s capacity to impact cultural norms is a much more salient feature to consider when evaluating its strategic worth. Many readily recognize this and contend that veganism’s true value comes from the way it challenges social norms irrespective of veganism’s marginal economic impact. For example, Smith argues that “Vegetarianism’s anti-hegemonic and anti-industrial stance forces contemporary culture to formulate and defend its principles, to explicitly justify the treatment of animal Others."[25] I disagree; passive veg(etari)anism does nothing of the sort. At its worst, passive veganism done solely within the privacy of one’s home does absolutely nothing to challenge societal norms; from a cultural perspective, one could just as well eat flesh in secret and have the same cultural impact, i.e., none. At its best, passive veganism practiced in the presence of carnism does little better to challenge hegemonic oppression; while it does, perhaps, demonstrate that eating animals is not necessary, in passively condoning the carnism of others this marginal benefit comes at the devastating cost of instantiating carnism as a morally-neutral personal choice.

But eating animals should not be treated as a morally-neutral personal choice in the way that we treat, for example, one’s decision to wear red or blue pants. Rather, eating animals is an act of violence and should be vociferously condemned as such. Just as passive veganism is problematic for its failure to do so, the Liberation Pledge’s power comes from its commitment to actively reject carnism as a morally-neutral personal choice. Instead, the Liberation Pledge goes beyond simply limiting one’s economic complicity to directly challenge the violent dietary practices of our culture(s). That is, its active practice forces carnism to defend itself. In doing so, the Pledge actuates the moral table turning that Regan called for:[26]

Contrary to the habit of thought which supposes that it is the vegetarian who is on the defensive and who must labor to show how his [sic] “eccentric” way of life can even remotely be defended by rational means, it is the non-vegetarian whose way of life stands in need of rational justification.

Carnism’s deconstruction requires active resistance, and the Liberation Pledge facilitates just that.

The Liberation Pledge’s power is further strengthened by its capacity to showcase the practitioner’s moral conviction via the personal sacrifice that stems from it. Simply put, practicing the Liberation Pledge can be difficult; however, this very difficulty enhances the Pledge’s impact on each of the three imbricated cohorts: (a) those whose ideologies remain conditioned by carnism; (b) the individual practitioner; and (c) the animal liberation movement collectively.

In relation to the first group—those who still eat animals—the practitioner’s personal sacrifice empowers their activism by clarifying its ethical motivation. Practicing the Liberation Pledge is no easy task, and others immediately recognize that. This notable sacrifice makes it clear to others that the practitioner is driven by a pursuit of justice, not personal pleasure, and consequently forces them to contend with the action as a form of activism rather than as a morally-neutral quirk. Whereas one’s choice to eat vegan silently in the presence of carnism allows others to understand it as a personal dietary decision—e.g., akin to eating gluten free[27]—practicing the Pledge serves to shift the frame and force others to seriously contend with the ideology motivating their activism. At the very least, this sows seeds of doubt about carnism within others, powerfully serving to erode the normalcy upon which the system is propped up.

Even better, reifying this position—that carnism is not a morally-neutral personal choice—often helps the activist to win outright ethical support. That is, by centering the ethics motivating one’s behavior, observers are more likely to follow suit for the same ethical reasons.[28] This strength of the Liberation Pledge is notable when compared to passive veganism, which fails to win ethical support in the same way. Even when passive vegan consumers explain their dietary choice as one rooted in animal ethics, they continue to frame it as their personal ethic. While this framing can readily win converts to eating plant-based for personal reasons like health and fitness (e.g., note the prominence of documentaries like What the Health and Game Changers), it fails to do so at the same scale for ethical reasons. But de-normalizing and dismantling carnism fundamentally depends upon promulgating a moral critique. As such, through emphasizing the activist’s moral convictions, the Liberation Pledge threatens carnism’s cultural hegemony beyond passive veganism’s capacity to do so.

With regard to the second group—the individual practitioner—the personal sacrifice invoked by the Liberation Pledge serves to toughen their resolve. Just as a monk’s asceticism functions to strengthen their soteriological commitment, so too do the practitioner’s personal sacrifices strengthen their moral conviction. Given the depth with which carnism has been embedded within societal norms, unshakable conviction is necessary to uproot it. As such, the Liberation Pledge provides one with frequent opportunities to practice and instill their commitment, every time serving to deepen their resolve and subsequent capacity to change the world for animals. Just as importantly, practicing the Liberation Pledge also protects one from needing to (sub)consciously normalize the carnism of others—an act that is often necessary to amiably dine with others eating animals—as doing so profoundly compromises both their conviction and efficacy as an activist.

The third cohort—the animal liberation movement—is collectively strengthened via the capacity of shared sacrifice to unify activists. Just as grueling pre-season training regimens are meant to strengthen group cohesion within athletic teams, the difficulty imposed by the Liberation Pledge functions in an analogous way. Seeing that one’s comrades are willing to voluntarily shoulder the same difficulties for the animal liberation movement poignantly demonstrates the group’s shared values and commitment to them. Given carnism’s social hegemony and the paucity of animal activists actively fighting it, this shared sacrifice promotes the solidarity necessary to transform the zeitgeist’s conception of nonhuman animals.

Practicing the Liberation Pledge may seem daunting at first, but it is in part this difficulty that makes the Pledge worthwhile. And when we consider our overwhelming privilege relative to the oppressed victims we are fighting for, the uncomfortable social interactions that can sprout from the Liberation Pledge are a paltry price to pay in fighting for their liberation.

III. Current Status & Historical Context

“A small body of determined spirits fired by an unquenchable faith in their mission can alter the course of history.”

—Gandhi[29]

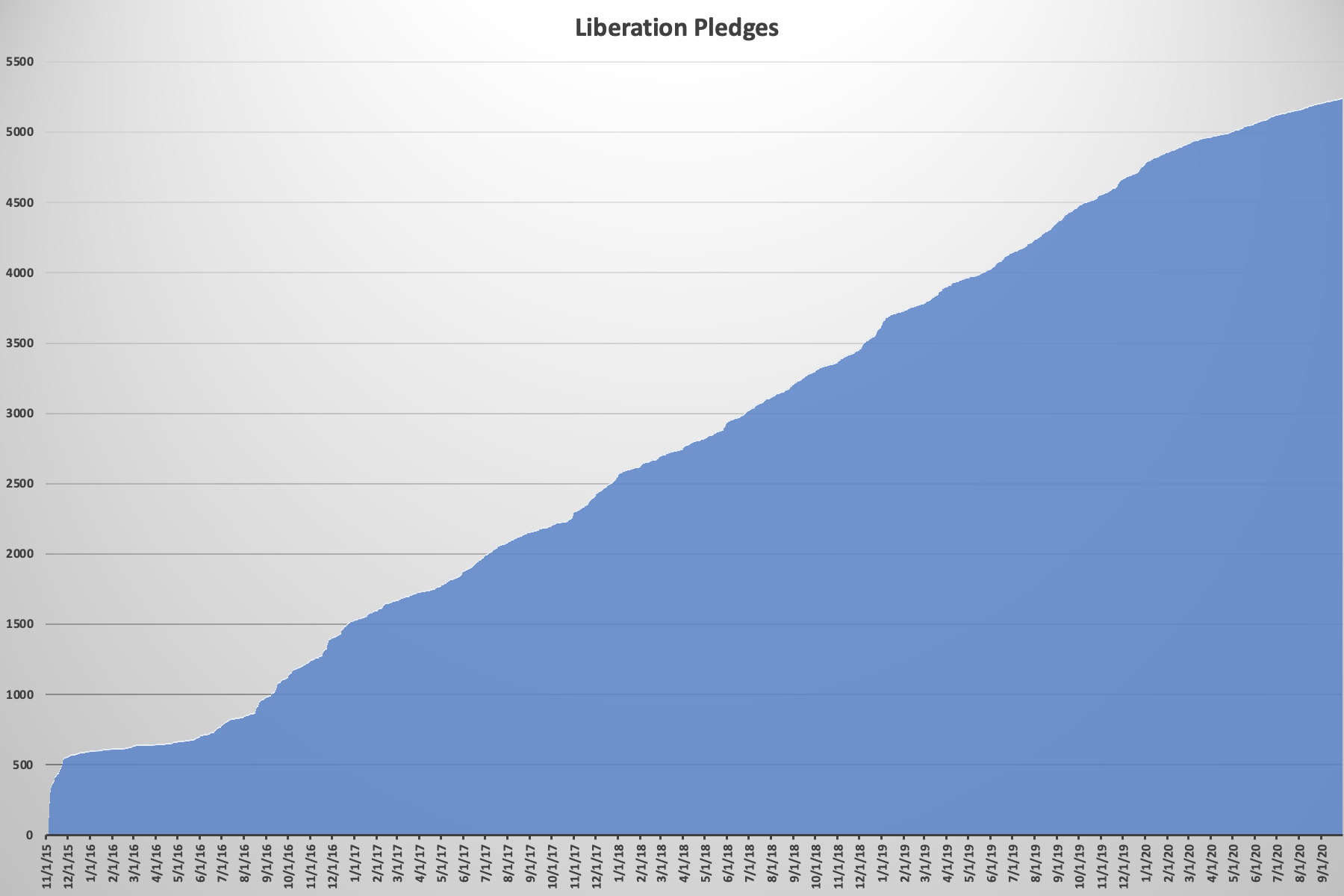

Is there reason to believe the theory of change articulated above is having the intended impact? In short, it remains too early to say. The formal Pledge and its campaign were launched in late 2015 in the weeks leading up to Thanksgiving. Since then, as of October 2020, nearly 5,200 humans from 98 countries and six continents have formally taken the Pledge.[30]

The graph below visually tracks the global uptake of the Liberation Pledge since its launch. Following a rapid spike of over 500 individuals taking the Pledge in the first month, the following six months saw relative stagnancy. However, since June 2016, there has been a remarkably consistent rate of uptake over the past four and a half years, albeit with a minor reduction beginning with the onset of Covid-19 (a reduction that, given the general decrease in activism alongside the limited ability to freely choose one’s social interactions, makes sense). This trend leads one to infer that those practicing the Liberation Pledge have found it worthwhile and have continued to promote it throughout their network.

Five thousand humans, it may be said, is clearly only a drop in the bucket. Even so, 5,000 humans actively practicing the Liberation Pledge around the world is still very relevant, very powerful. Everyday these 5,000 activists interact with strangers and challenge their beliefs. They form a bubble of anti-speciesism wherever they go, where this ethic is a defining norm of all their interactions. In doing so, the goal is not to segregate themselves from the carnist milieu, but rather confront and perforate it everywhere they go.

But while these individual bubbles are powerful, the Liberation Pledge’s true capacity for affecting social change is dependent upon concentrated growth. Such geographic concentration is critical for two reasons. First, concentration dramatically empowers the Pledge’s ability to challenge carnism’s perceived normalcy. For in every additional instance an individual meets a Pledge practitioner, the more normal taking the Pledge seems and the less normal failing to do so becomes. As a result, such concentration serves to reduce social barriers to adopting the Pledge while also increasing social pressure to follow suit. Second, as numbers of impassioned activists grow within a community, so too does their capacity to build the political power required to seriously challenge carnism. Laws regulating the consumption of animal products can only manifest once a sufficient threshold of constituents avidly support it, and the geographic concentration of Pledge practitioners function to create this committed base of support.

So while the Pledge’s historically linear trend is a positive sign, its success ultimately depends upon concentrated, exponential growth moving forward. And this is where the importance of the Liberation Pledge’s third goal—encouraging others to take the Pledge—comes in. Carnism’s moral license will dissolve—even if initially just at the municipal level—once the number of Pledge practitioners reaches a critical mass, and it is the role of early adopters to create the foundation for this to happen.

While the Liberation Pledge remains too young to fairly assess its success, there is historical reason to believe that this campaign, beginning with relatively few individuals, has the power to grow rapidly and transform society. The Liberation Pledge’s theory of change is inspired by the successful campaign to end foot binding in China.[31] For a thousand years, this campaign struggled to gain traction against foot binding’s cultural hegemony. However, it built rapid momentum in 1890 with the initiation of a public pledge where families would promise to one, never bind their daughter’s feet, and two, refuse to allow their sons to marry women with bound feet.[32] Appiah explains how the campaign transformed a region south of Beijing from 99% to 0% support in a matter of thirty years.[33] This movement grew exponentially, and rapidly led to the societal stigmatization of the practice.

Notably, as Hsiung points out, the similarities between both campaigns and the oppression they target are striking.[34] First, carnism today, like foot-binding historically, is an oppressive practice most in society are born into and conditioned to accept as normal. Second, like foot-binding, tradition is used to justify carnism’s continuation. And third, like foot-binding, individuals who attempt to extricate themselves from carnism for ethical reasons are ridiculed and ostracized, a tactic that enables the oppressive practice to maintain its normalcy and cultural hegemony. Given their stark similarities, there is reason to see the Liberation Pledge not only as an appropriate reaction to carnism but as a strategy with the potential to be transformative in the long run.

Early anecdotal evidence lends weight to this claim. While the impact of a practitioner’s moral stance leading to their entire family shifting to veganism are common, larger examples include one individual’s Pledge leading to nearly their entire high school eating plant based on campus.[35] Although the Liberation Pledge remains in its formative years, these examples give reason to expect its power and efficacy to grow. As activists, it is our responsibility to make that happen.

IV. Critiques of the Liberation Pledge

“The fact that you can only do a little is no excuse for doing nothing.”

—John Le Carré[36]

Critiques of the Liberation Pledge fall into three categories: (a) that it is ineffective; (b) that it is harmful; and (c) that it is immoral. Arguments within the first category—that the Liberation Pledge is ineffective—make the case that adopting the Liberation Pledge does not actually challenge the normalcy and cultural hegemony of carnism, a consequence they argue renders the Pledge unnecessary. This perspective is not a case against the Liberation Pledge, per se, but rather a critique of its relevance and value.

The second and third categories, on the other hand, do argue against the adoption of the Liberation Pledge. Whereas critiques within the second category—that the Liberation Pledge is harmful—may accept that the Pledge is effective in some ways, they argue that it is more detrimental than helpful. Consequently, even if they may hold the ideals of the Liberation Pledge to be admirable, critics from this camp argue against its practice from the basis of a cost/benefit analysis. Similarly, while critiques from the third category—that the Liberation Pledge is immoral—may also accept that the Pledge is effective in some ways, they argue that aspects of its very practice are immoral and as such it should not be practiced or promoted. This article collectively is a refutation of arguments that fall within the first category; as such, in this section I consider and respond to the seven central arguments that fall within the latter two.

1. Misses an Opportunity to Engage with Carnism.

One critique claims that the Liberation Pledge compromises the ability of activists to engage with individuals as they invoke the texts of carnism. As such, it argues that the Liberation Pledge does more harm than good. Activists who hold this position instead argue that we should be eating at carnist tables, both demonstrating that it is possible to eat vegan while also condemning their practice.[37]

However, there is reason to doubt the efficacy of this tactic. As Cato cautioned, “It is a difficult task, O citizens, to make speeches to the belly which has no ears."[38] Arguably one of the least fruitful places to talk with others about the immorality of their action is while they are enacting it. In such situations the cognitive dissonance between one’s actions and values is simply too deafening to fruitfully engage with. With relation to carnism, this cognitive dissonance climaxes at each meal that animal products are present. As so many activists know, for all but the most effective outreachers attempting to convince someone to “go vegan” while flesh is on their fork is a fool’s errand. Midgley clearly articulates this tension, explaining that while meat eaters see themselves as “eating life,” vegan consumers see them as “eating death."[39] As such, Midgley observes that “there is a kind of gestalt-shift between the two positions which makes it hard to change, and hard to raise questions on the matter at all without becoming embattled.”[40]

Moreover, due to the increased tension present at mealtimes, many activists are unwilling to have these direct conversations and speak truth to power in the first place. Rather, many vegan eaters while dining in the presence of carnism feel silenced and isolated, personally stressed by seeing their loved ones consuming violence while disquieted by not knowing how to respond. Instead, I believe it is more effective to emphatically condemn carnism and boycott every meal it is invoked, enabling thoughtful discussions to be had away from the plate.

Even better is having these conversations over shared vegan food. The purpose of the Pledge is not to limit our interactions with carnists, per se, but rather to bring a wider audience to our vegan table. For while secretly taking the Pledge and eating at home alone is at least not harmful in the way that silently condoning the carnism of others is, neither is it actively productive. Instead, the idea is for practitioners to invite those who eat animals to share a vegan meal with them. For just as there is little hope for fruitfully discussing the immorality of carnism as the other invokes its text, there is no better context to discuss the morality of veganism than when sharing vegan food. Until that is possible, the best alternative remains respectfully boycotting interactions based around carnism. For not only does this patience avoid counterproductive interactions, it expedites the process for others to decide differently and elect to eat vegan alongside the practitioner in the future.

2. Damages Relationships.

A second critique argues that taking the Liberation Pledge can damage relationships, a position that contends the Pledge is consequently both harmful and immoral. This critique is most salient in regard to familial, social, and professional relationships.

Let’s begin by considering the claim that as a result of straining familial/social relationships, the Liberation Pledge does more harm than good. This argument rests on the premise that by taking such a firm stance, practitioners run the risk of damaging their relationships. This risk, the argument goes, further risks compromising one’s mental-health and support system. Given these possibilities, it is thus argued that practicing the Liberation Pledge limits the activist’s ability to be as effective as they otherwise would outside of these contexts.

While an important consideration, it is also important to note that perhaps even more compromising to one’s mental health is seeing loved ones consume the products of violence. Sitting alongside family or friends and feigning normalcy while the scent and sight of cooked bodies floods one’s system is a far cry from nurturing self-health. Rather, in order for an animal liberationist to eat around others consuming animal products they must either (a) accept the normalcy of the action, or (b) deeply bury their true feelings; while the former compromises one’s ability to be an effective activist, the latter compromises one’s mental wellbeing.

Moreover, while taking the Liberation Pledge in some cases can damage relationships in the short run, it lays the foundation for a much stronger relationship in the long term. Healthy relationships are built upon trust and mutual respect, and forcing oneself to stay silent and choke back moral concerns while surrounded by loved ones at tables of violence negates both. Furthermore, many (including myself) find the directness of the approach a salve to previous relational friction. By calmly and explicitly addressing the elephant in the room before mealtimes—our veganism and condemnation of their carnism—we not only clear the underlying tension that would have otherwise existed, but do so in a space away from the plate where our message is more likely to be sincerely heard and received.

Even so, familial tension can often be the hardest, as these relationships are largely out of the practitioner’s control; moreover, family members tend to be acculturated to one’s past habits and can bristle when their loved ones “suddenly” change. However, the depth of these relationships often means that the practitioner’s family members are eager to find recourse, and—assuming the practitioner is compassionate and patient in the process—there is reason to expect this tension can be ironed out in the long run. Furthermore, for many, familial interactions are sporadic throughout the year, and as such the tension that can arise as a result of one’s commitment to the Liberation Pledge is made more tolerable.

While close friendships are often much more constant, so too are they more fungible. In this context, an activist must ask themself if they want to have friends who actively endorse the murder of innocent individuals, or if they should instead be standing with allies against those who brutalize them.[41] To be clear, that is not to say the practitioner should abandon all their close carnist friendships, but rather encourage their current friends to eat plant based around them while actively exploring new friendships with vegan consumers. While admittedly challenging, the initial difficulty imposed on social relationships by the Pledge provides a valuable impetus to become more integrated within the activist community, a reality with clear positive impacts to the movement.[42]

Much the same argument and responses can be made in regard to how practicing the Liberation Pledge can hamper workplace dynamics. However, rather than just compromising one’s mental health, the concern is centered on damaging relationships critical to one’s professional success, and consequently, their efficacy as an activist outside of work. However, similar to above, is lying to coworkers about one’s feelings in relation to animal exploitation a good foundation for a positive relationship? Moreover, if one would be discriminated against in the workplace based on their activism, is that a healthy or positive space for the individual to be working in the first place?

A powerful rebuttal to these questions justifies the activist tolerating carnism in the workplace when done for the purpose of empowering their activism outside of work, a line of thought analogous to effective altruism’s framework of “earning to give."[43] But the purpose of earning to give shouldn’t force one to compromise their morality; on the contrary, in Section V I argue that silence in the face of violence is itself immoral. As such, I argue that higher economic gains or economic stability do not justify staying silent to assuage coworker/supervisor guilt.

To be fair, I recognize that the notion of what constitutes a “healthy” or “positive” relationship is fraught with ambiguity. And while I do believe that healthy and positive relationships are built upon trust, others may very well disagree; instead, they may hold that maintaining relationships based upon deception and insincerity is a just cost to pay to facilitate their activism outside of these relationships. In some extreme cases, that may be true. However, more often than not, I believe this argument stems from carnism’s social hegemony and a misunderstanding of how it is perpetuated. Simply put, tolerating the carnism of others does more to promulgate the oppressive system than does filling a role on a slaughterhouse disassembly line, for the root issue lies not with slaughterhouse workers but with those who normalize the demand for such labor. As such, for those who would refuse to work at a slaughterhouse irrespective of how much it facilitated their activism outside working hours, consistency asks them to do the same with regard to rejecting the carnism of others in the workplace.

To be clear, I fully recognize that some of these positions depend upon a level of privilege. A single parent, for example, may not have the luxury of losing their job due to their “anti-social” behavior. Nor may a teenager have the freedom to practice the Liberation Pledge fully. I further recognize that individuals who already face marginalization due to other aspects of their identity may both have less room to navigate added stigma from their activism and may receive heightened stigma against their activism due to their identity.[44] That said, at least with the regards to the latter, it is worth mentioning how oppressed groups have long taken on veganism as part of their own liberatory struggle. Feminists like Carol Adams,[45] prison abolitionists like Angela Davis,[46] and anti-imperialist groups like the MOVE organization[47] have all helped to show how speciesism is imbricated with other systems of oppression, and subsequently how dismantling one requires dismantling all. Informed by this intersectional understanding, adopting the Liberation Pledge can actually be used as a tool for fighting one’s own oppression.

However, despite this theoretical endorsement, willingly accepting further marginalization is easier said than done. As such, as acknowledged in Section V, such cases may very well merit a modified response. I simply ask that when considering such modifications, the harm of tolerating carnism be weighed similarly to how society considers already stigmatized social harms (e.g., beating a dog in the cultural context of the United States), and not be discounted as an unimportant consideration undeserving of personal hardship. That is, if in a certain context a U.S. resident would be unwilling to passively tolerate watching a dog be beaten, so too should the person object to carnism practiced in an analogous context.

The second dimension of this critique argues that damaging social relationships as a result of practicing the Liberation Pledge is immoral, and as such, that the Pledge ought not be practiced or promulgated. This argument extends from the premise that we have special duties to loved ones that transcend animal ethics and that it is immoral to ignore those. The veracity of this claim—that we have special duties to loved ones that transcend their carnism—is outside the scope of this article. However, refusing to eat with loved ones while they consume violence does not preclude one’s ability to fulfill any moral obligations we accept owing, as practitioners can still spend meaningful time with loved ones between meals. Moreover, if we accept the premise of familial or social duties, then so too do a practitioner’s loved ones have a duty to make the practitioner feel supported and understood. As such, if family members or friends refuse to eat plant based around their loved one, then it seems the best space to collectively fulfill their duties to one another exists away from the dinner table.

3. Overly Radical.

A third critique argues the Liberation Pledge is harmful because it is “too radical.” That is, that its perceived extremeness serves to push others away that might otherwise be open to changing if presented with a more moderate approach, and as a result, generates a net negative impact.

In short, I believe this argument is unfounded and not made in good faith; rather, I believe it is weaponized as justification for individuals to continue their carnistic habit patterns by shifting blame from themself to the “radical” practitioner. While this framework may help to assuage the critic’s own cognitive dissonance, in doing so it demonstrates how deeply entrenched they are within carnism and belies their claim of feigned openness/neutrality. For in reality the commitment to not condone the violence of others is in no way radical. Rather, the reason such critics perceive the Pledge as extreme is due to how normalized this violence has become. On the contrary, given that the Pledge’s theory of change is centered in its ability to undermine this normalcy, its very practice serves as a mechanism for targeting the root of such critiques.

Moreover, these types of vehement rejections are in part what the Liberation Pledge seeks to uncover. As Martin Luther King Jr. explained:[48]

[W]e who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with.

It is only in identifying this underlying tension that it can be overcome. In unearthing such conflict, the purpose of the Liberation Pledge is not to convince 100% of the population to support veganism or animal liberation; rather, the purpose of this activism is to force individuals to choose a side, to make complacency and indecision so uncomfortable that they are forced to directly confront the issue and make a concrete decision one way or the other.

In doing so—forcing individuals to explicitly choose sides between oppressors and oppressed—some individuals will inevitably be pushed away. However, this is a necessary and worthwhile cost. Simply put, neutrality within an oppressive context means acceptance of the oppression, a point vociferously made by Martin Luther King Jr.: “The hottest place in Hell is reserved for those who remain neutral in times of great moral conflict.”[49] However, given the extent of carnism’s cultural embeddedness, most individuals have never been forced to think deeply about the issue; instead, they understandably follow the path of least resistance by uncritically accepting culturally dominant practices. So for many it isn’t that they are consciously remaining neutral, per se, but that they are unaware of the conflict to begin with. As such, practicing the Liberation Pledge serves to demonstrate to others that this conflict exists, and that they have historically been neutral within it.

Thankfully the vast majority of humans in the United States[50] and majority of humans around the world[51] already support animal welfare and oppose animal cruelty. So while uncovering such underlying tension and forcing individuals to confront the violence of carnism head on may indeed push some individuals away, the individuals it pushes away were never allies to begin with. Rather, forcing them to confirm their support of animal exploitation is a necessary cost to empower the greater majority to crystalize their support for animal rights and realign their actions as required.

4. Proselytizing is Immoral.

A fourth critique argues the Liberation Pledge is immoral for pushing one’s beliefs onto others. That irrespective of the veracity of one’s belief, it is immoral to push it unto others without their consent, and as such, that the Liberation Pledge ought not be practiced nor promoted.

While the critique against proselytization is fairly charged with regard to morally-neutral personal choices, it does not apply to decisions that impact others. My right to swing my fist through the air ends with another’s right to not be hit. While having one’s favorite type of cuisine be Italian is a morally-neutral personal choice, electing to have a pasta dish cooked with the dairy and flesh of a cow is not. Consuming the flesh of another should be understood as a morally intolerable action, as it profoundly impacts the welfare of another. As such, neither we nor others have the right to do so.

On the contrary, those of us who have been privileged to break free from social conditioning and develop the understanding of carnism’s violence have a responsibility to share this understanding with others. Practice of the Liberation Pledge is simply the logical continuation of a vegan ethic; once we understand that veganism is not a personal choice but rather a moral imperative, it becomes incumbent on us to extend this understanding and knowledge outward. The vast majority of the world’s vegan consumers were not born as such; after exposure to facts we decided to make the change, and we can play a role in helping those around us do the same.

As an instructive example, society readily condemns sexual violence irrespective of the perpetrator’s sexual desires. In this context, the perpetrator’s personal interests are rendered irrelevant. Indeed, rather than being perceived as problematically proselytizing, unapologetically condemning such violence has become the norm. So too must society come to collectively condemn carnism, regardless of one’s taste preferences.

5. Cultural Differences.

A fifth critique questions the morality of practicing the Liberation Pledge in the context of foreign cultures. It is one thing, proponents of this argument claim, to practice the Pledge while embedded within one’s own culture, but problematic to do so in others.

However, while cultural differences are deeply important and deserving of respect, that is not a justification for moral relativism.[52][53] I assume that most readers will agree that racism, (hetero)sexism, and other forms of discrimination are wrong regardless of the culture in which they are practiced. For example, just because a specific culture has historically denied personal liberty and freedom to women does not give those conditioned within this culture license to continue doing so. Human supremacy should be dealt with in the same way. Culture simply does not justify the oppression of nonhuman animals.[54]

Moreover, culture is not a uniform nor a static entity; on the contrary, cultures are constantly evolving in large part due to internal contestation. Within this context cultural natives are best positioned to lead change, and examples abound of folk doing so with regard to animal liberation.[55][56] But while it is often not appropriate for outsiders to lead in affecting social change in foreign cultures, that does not negate the importance of maintaining one’s ethical values and serving as allies to culturally native animal liberationists when in cultures foreign to one’s own. Practicing the Liberation Pledge is a basic but responsible way to do so.

That said, other cultural differences that do not violate the rights of others should be honored and respected. As such, the explanation of the Liberation Pledge can and should look different depending on the cultural context. Stated differently, while it may very well be appropriate to convey veganism and one’s commitment to the Liberation Pledge in varying ways depending on the cultural context, the moral necessity of maintaining one’s own veganity does not shift. Nor do I believe it problematic to maintain one’s Pledge in these contexts. On the contrary, making such exceptions when embedded within cultures foreign to one’s own can be interpreted as a form of chauvinism, in that the practitioner condescendingly believes foreign cultures are incapable of understanding the ethics/rationale of the Liberation Pledge.

As a personal example, I have easily and fruitfully maintained my own commitment to the Liberation Pledge in Nicaragua (where I served as a Peace Corps Volunteer), in Colombia (where I worked for nearly a year), and throughout south and southeast Asia (where I cumulatively spent a year). In each of these contexts, while the explanation at times did take longer than it generally does in the United States (my native culture), more often than not it was received with more grace and support. To be clear, I recognize that these anecdotal examples are just that, anecdotal, and simply share them to explain my personal confidence regarding the Pledge’s international feasibility.

In the case of extreme outliers—e.g., Inuit who depend upon seal flesh or Sherpa who depend upon yak milk to survive[57]—the discussion becomes more complex. Given the highly atypical character of these outliers along with the nuance needed to address them adequately, it is an issue I set aside in this article (though the curious reader may find discussions from Kim[58] and Robinson[59] of interest). That said, apart from such outliers the ethics around animal edibility are very clear and should be advocated for as such.

6. Dependents.

A sixth argument against the Liberation Pledge holds that because the Pledge is not universally practicable, advocating for its universal adoption is immoral. For example, there are minors, humans with disabilities, incarcerated individuals, and other exceptions where humans with antispeciesist values are unable to choose their diet or the circumstances in which they are able to eat. I resonate with the unique challenges some individuals face in relation to adoption of the Liberation Pledge and explore the topic in more detail in the final section. However, I do not contend that adopting the Liberation Pledge is universally mandatory and acknowledge the reality that some humans are simply unable to practice it. That said, accepting that some individuals are unable to practice the Liberation Pledge is not a justification against the Pledge itself nor a rationale for others with different circumstances for not maintaining it.

7. Moral Licensing.

Moral licensing describes the practice wherein one justifies their immoral acts based on other moral acts they have taken. For example, someone justifying the carbon footprint of their travel by noting their practice of recycling. As such, moral licensing can give the impression that all one needs to do to be a good person entails what they are already doing.[60] In the context of this article, the moral licensing critique argues that practicing the Liberation Pledge encourages activists to abstain from taking more poignant and effective activism, thus making the Pledge’s efficacy net negative.

This argument, however, can be made with regard to any form of activism. As such, acknowledging its credibility here would justify never doing any type of novel activism. However, at least in this context, the opposite impact is more likely. Powerfully and publicly acting on one’s values every mealtime helps the practitioner to build their confidence and conviction. And rather than limiting one’s additional activism, this impassioned conviction more often spills over to inspire continued engagement in the movement.

Having canvased and responded to these seven central critiques, I contend that the main arguments against the Liberation Pledge, despite perhaps meaning well, are unfounded. With regard to critiques within the first category discussed—that the Liberation Pledge does more harm than good—I argue that they largely emerge from a failure to understand the mechanisms that make the Liberation Pledge effective and powerful. On the contrary, more often than not these critiques target what I hold to be the most powerful and effective aspects of the action. In response to the second category of critiques discussed—that practicing the Liberation Pledge necessitates immoral actions—I argue that these actions are not inextricably connected to the Pledge itself, and that they can be dealt with in a sensitive way that addresses the moral concern without compromising the practice of the Pledge.

To be clear, this is not to say that practicing the Liberation Pledge is necessarily free from unintended detrimental impacts; rather, I hold that these impacts are not inherent to the Pledge itself. As such, activists can and should work to mitigate the downsides pointed out in these critiques—e.g., bringing those who eat animal products to a vegan table rather than just blocking them out of their lives, communicating one’s position calmly and empathetically, centering messaging around the suffering of individual animals rather than the immorality of others, etc. When practiced thoughtfully and strategically, I argue that the critiques of the Liberation Pledge carry little weight; on the contrary, I contend that thoughtfully and strategically practicing the Pledge is morally consistent and profoundly effective.

V. Ethical Imperative to Take the Pledge?

“There may be times when we are powerless to prevent injustice, but there must never be a time when we fail to protest.”

—Elie Wiesel[61]

Is there a moral imperative for one to take the Liberation Pledge? To answer this, we must first consider if there is a moral imperative to eat a vegan diet. Unfortunately, an in-depth exploration of that question is outside the scope of this article. Without delving into the nuances of this question—one that has already been explored at length by writers like Regan[62] and Francione and Charlton[63]—I accept that there is a moral imperative to eat a vegan diet, what Plumwood[64] pejoratively calls ontological vegetarianism.

More specifically, I advocate a position of aspirational veganism as articulated by Gruen and Jones, whereby the practitioner eats 100% plant based in a way meant to minimize harm.[65] This clarification is important as a cruelty-free diet does not exist. We are entropic beings whose existence requires energetic consumption, and as such our lives inevitably result in the death and suffering of others.[66] However, eating plant based is a level of magnitude less harmful than a carnist diet, and is a basic requirement of aspirational veganism.

While accepting the framework of aspiration veganism, it is worth noting that carnism’s immorality is not fixed. While accepting ontological veganism—that it is always immoral to consume nonhuman animals and their products—we can also hold that extenuating circumstances can make this position more or less immoral. This perspective is influenced by the framing of contextual moral vegetarianism, a concept that has long been argued for by ecofeminists who recognize that “gender, race, class, ethnicity, and location can create genuine difficulties with choosing a vegetarian diet."[67]

To be clear, acceptance of contextual moral vegetarianism does not imply an acceptance of moral relativism; rather, it accepts that under extreme conditions—e.g., killing an animal to feed one’s child[68]—the moral question becomes less stark, more nuanced. However, the need to feed one’s child does not magically make the killing of another (a)moral; violence, I contend, is always prima facie wrong, even when there are morally relevant justifications. By unequivocally holding violence as prima facie wrong, the onus of justifying violence is put on the individual enacting it.[69] These justifications, however, tend to be radical outliers from the lived experiences of everyone reading this article; as such, eating 100% plant based is almost certainly possible and I posit morally required for everyone reading this sentence.

However, before answering if there is a moral imperative to take the Liberation Pledge we must also consider if there is a moral obligation to actively resist injustice. This is particularly striking if we accept that veganism made at the individual level is a form of passive—and not active—resistance. In “Famine, Affluence, and Morality,” Singer essentially argues that if we accept (a) that suffering and death are very bad; and if we accept (b) that we are morally required to do something if we can prevent very bad things from happening without sacrificing something of comparable moral significance; then we must accept (c) that we are morally required to work to prevent suffering and death if doing so does not require sacrificing something of comparable moral significance.[70] As previously noted, carnism necessitates astronomical levels of suffering and death. Moreover, most common forms of activism meant to reduce this harm—the Liberation Pledge included—require sacrifices of low moral significance. As such, accepting Singer’s two premises listed above should lead us to view actively resisting carnism as morally required.

Thus, if we accept the premise that (in most contexts) veganism is morally required, just as accessible activism to promote veganism and condemn carnism is morally required, does it then follow that there is a moral imperative for adopting the Liberation Pledge? In short, not necessarily. If one accepts that the Liberation Pledge is an effective and expedient tool in fighting for animal liberation, then it can be strongly argued that taking the Pledge is morally required, especially because doing so is relatively easy and the issue it targets is devastatingly massive. Conversely, if one rejects the premise of this article and instead maintains that the Liberation Pledge is ineffective, then adoption of the Pledge would obviously not be morally required.

However, even if it can be argued that it is okay to not take the Pledge, that does not mean it is okay to be silent. Rather, choosing to eat around carnism morally necessitates speaking out clearly and directly. Failing to do so—to poignantly and explicitly object to another’s consumption of animal products whenever it happens—empowers the carnistic consumer to continue viewing eating animals as a morally-neutral personal choice, one they have the right to continue choosing. Thus, not only does such silence fail to challenge carnism’s normalcy, but it further serves to license the reproduction of carnism’s cyclical violence. As such, despite not themselves ingesting the products of violence, the passive vegan practitioner is not absolved of culpability. Rather, they too share responsibility for the violence that stems from carnism.

However, as I hope has been made clear, I believe that taking the Liberation Pledge is more effective in deconstructing carnism than simply vocally condemning the practice. Given that position, I contend that adopting the Liberation Pledge is morally required when possible. This caveat, when possible, is important to articulate. I acknowledge that the Liberation Pledge is not universally practicable, and in these instances do not hold the individuals unable to eat vegan or follow the Pledge morally culpable (though again, that does not suddenly make the practice of carnism [a]moral, but simply shifts the ethical derision onto the shoulders of the caretaker). For example, there are minors, humans with certain disabilities, incarcerated individuals, and others with anti-speciesist values unable to choose their diet or the circumstances in which they are able to eat. That said, these examples are clearly exceptions, not the rule. And given my position that the Liberation Pledge is an effective tool for deconstructing carnism, as long as practicing the Liberation Pledge is possible and does not require sacrificing something of comparable moral significance, I do view its practice as morally required.

On the contrary, many may argue that the Liberation Pledge is itself too passive. That accepting the moral urgency of animal liberation alongside Singer’s rationale that favors active resistance should compel us to take much bolder and more direct actions. I emphatically agree. However, a valid critique of insufficiency does not detract from the Pledge’s necessity. I strongly support activists taking further action beyond the Liberation Pledge, and simply hold that it is one tool amongst many that should be employed by liberationists.

What we eat is deeply political, and it is time for activists to live out the consequences of this reality by refusing to condone the consumptive violence of others. It is my hope that in reading this you leave convinced to uptake the Pledge yourself, and if not, that the seeds for such action have been planted and await germination. In accordance with that desire, I end with a reference to Martin Luther King Jr.’s shared sentiment: “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends." [71]

- ^

Corredor, J. M. (1957). Conversations with Casals (p. 11). Dutton.

- ^

Best, S., Nocella, A. J., Kahn, R., Gigliotti, C., & Kemmerer, L. (2007). Introducing critical animal studies. Journal for Critical Animal Studies, 5(1), 5–6.

- ^

- ^

The Liberation Pledge. (2020).

- ^

Torres, O. (2015). Making the liberation pledge work for you. Direct Action Everywhere.

- ^

Swords to ploughshares. (2020). In Wikipedia.

- ^

Muller, M. A., & Brown, A. (2010, September 9). The Plowshares Eight: Thirty years on. Waging Nonviolence.

- ^

Tuttle, W. M. (2005). The world peace diet: Eating for spiritual health and social harmony (p. 1). Lantern Books.

- ^

Schlottmann, C., & Sebo, J. (2019). Food, animals, and the environment: An ethical approach (p. 71). Routledge.

- ^

Kaneda, T., & Haub, C. (2020). How many people have ever lived on Earth? Population Reference Bureau.

- ^

Schlottmann & Sebo, supra note 9, at 189.

- ^

Wadiwel, D. J. (2015). The war against animals. Brill.

- ^

Abbey, E. (1989). Beyond the wall: Essays from the outside (Nachdr.). Holt.

- ^

Kymlicka, W., & Donaldson, S. (2014). Animal rights, multiculturalism, and the left. Journal of Social Philosophy, 45(1), 116–135.

- ^

Best et al., supra note 2.

- ^

Joy, M. (2011). Why we love dogs, eat pigs and wear cows: An introduction to carnism; the belief system that enables us to eat some animals and not others. Conari Press.

- ^

Chambers, R. (1996). The unexamined. Minnesota Review, 47, 141–156.

- ^

Joy, supra note 16.

- ^

Chiles, R. M., & Fitzgerald, A. J. (2018). Why is meat so important in Western history and culture? A genealogical critique of biophysical and political-economic explanations. Agriculture and Human Values, 35(1), 1.

- ^

Bartky, S. L. (1975). Toward a phenomenology of feminist consciousness. Social Theory and Practice, 3(4), 22.

- ^

Gruen, L. (2011). Ethics and animals: An introduction (p. 102). Cambridge University Press.

- ^

Adams, C. J. (2015). The sexual politics of meat: A feminist-vegetarian critical theory (p. 29). Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.

- ^

Benningstad, N. C. G., & Kunst, J. R. (2020). Dissociating meat from its animal origins: A systematic literature review. Appetite, 147, 104554.

- ^

Kagan, S. (2011). Do I make a difference?: Do I make a difference? Philosophy & Public Affairs, 39(2), 122.

- ^

Smith, M. (2002). The ‘ethical’ space of the abattoir: On the (in)human(e) slaughter of other animals. Human Ecology Review, 9(2), 55.

- ^

Regan, T. (1975). The moral basis of vegetarianism. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 5(2), 203.

- ^

Hsiung, W. (2009). Boycott veganism. 8

- ^

Wheeler, L. (1966). Toward a theory of behavioral contagion. Psychological Review, 73(2), 179–192.

- ^

Gandhi. (1936, November 19). Harijan. Harijan, 341–342.

- ^

The Liberation Pledge, supra note 4.

- ^

Hsiung, W. (2017, December 6). How animal lovers are transforming Thanksgiving. Huffpost.

- ^

The Liberation Pledge, supra note 4.

- ^

Appiah, K. A. (2010). The honor code: How moral revolutions happen. W.W. Norton.

- ^

Hsiung, supra note 31.

- ^

Aspey, J. (2017, June 12). Eat at tables where animals are served? (W/ Wayne Hsuing, DxE) [Video]. YouTube.

- ^

Le Carré, J. (2008). A most wanted man. Scribner.

- ^

Aspey, supra note 35.

- ^

Giehl, D. (1979). Vegetarianism: A way of life (p. 128). Harper & Row.

- ^

Midgley, M. (1998). Animals and why they matter (p. 22). University of Georgia Press.

- ^

Id.

- ^

Hsiung, supra note 27, at 9.

- ^

Chenoweth, E., & Stephan, M. J. (2013). Why civil resistance works: The strategic logic of nonviolent conflict. Columbia University Press.

- ^

Singer, P. (2015). The most good you can do: How effective altruism is changing ideas about living ethically (pp. 39-54). Yale University Press.

- ^

Greenebaum, J. (2018). Vegans of color: Managing visible and invisible stigmas. Food, Culture & Society, 21(5), 680–697.

- ^

Adams, supra note 22.

- ^

Davis, A., & Lee Boggs, G. (2012, March 2). On revolution: A conversation between Grace Lee Boggs and Angela Davis.

- ^

Pilkington, E. (2018, July 31). A siege. A bomb. 48 dogs. And the black commune that would not surrender. The Guardian.

- ^

King Jr., M. L. (1963, April 16). Letter from a Birmingham jail.

- ^

King Jr., M. L. (1967, April 15). April 15 mobilization to end the war in Vietnam.

- ^

Reese, J. (2017). Survey of US attitudes towards animal farming and animal-free food October 2017. Sentience Institute.

- ^

Anderson, J., & Tyler, L. (2018). Attitudes toward farmed animals in the BRIC countries. Faunalytics.

- ^

Brown, M. F. (2008). Cultural relativism 2.0. Current Anthropology, 49(3), 363–383.

- ^

Jarvie, I. C. (1993). Relativism yet again. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 23, 537–547.

- ^

Gruen, L. (2001). Conflicting values in a conflicted world: Ecofeminism and multicultural environmental ethics. Women & Environments International Magazine, 16–19.

- ^

Gaard, G. (2001). Tools for a cross-cultural feminist ethics: Exploring ethical contexts and contents in the Makah whale hunt. Hypatia, 16(1), 1–26.

- ^

Robinson, M. (2013). Veganism and Mi’kmaq legends. The Canadian Journal of Natural Studies, 33, 184–196.

- ^

Arnaquq-Baril, A. (2016). Angry Inuk [Film].

- ^

Kim, C. J. (2015). Dangerous crossings: Race, species, and nature in a multicultural age (pp. 205-2520. Cambridge University Press.

- ^

Robinson, M. (2016). Is the moose still my brother if we don’t eat him? In J. Castricano & R. R. Simonsen (Eds.), Critical perspectives on veganism (pp. 261–284). Springer International Publishing.

- ^

Schlottmann & Sebo, supra note 9, at 190.

- ^

Wiesel, E. (1986, December 11). Nobel Lecture: Hope, despair and memory.

- ^

Regan, supra note 26.

- ^

Francione, G. L., & Charlton, A. (2015). Animal rights: The abolitionist approach. Exempla Press.

- ^

Plumwood, V. (2000). Integrating ethical frameworks for animals, humans, and nature: A critical feminist eco-socialist analysis. Ethics and the Environment, 5(2), 285–322.

- ^

Gruen, L., & Jones, R. C. (2015). Veganism as an aspiration. In B. Bramble & B. Fischer (Eds.), The moral complexities of eating meat (pp. 153-171). Oxford University Press.

- ^

Marder, M. (2013). Is it ethical to eat plants? Parallax, 19(1), 29–37.

- ^

Gruen, supra note 21, at 93.

- ^

Curtin, D. (1991). Toward an ecological ethic of care. Hypatia, 6(1), 70.

- ^

Regan, supra note 26, at 188.

- ^

Singer, P. (1972). Famine, affluence, and morality. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1(3), 229-243.

- ^

King Jr., M. L. (1967, November). The trumpet of conscience. Steeler Lecture.

This post has five comments; one offers a critique, and the other four are extremely positive. All four positive comments come from accounts which, like that of the post, are newly registered with no sign of other interaction. Unlike PabloAMC's comment, none of the four display much familiarity with EA principles or considerations. They have low karma / vote ratios*, suggesting they were upvoted by sub-1000 karma accounts, and possibly strongly upvoted once by a 10+ karma account.

* 6/5, 5/4, 4/4, 4/3 at time of writing.

This is a good observation. You were not the only one to notice this.

Note that Nico Stubler is an activist and it is reasonable and plausible that he has organically encouraged people to comment.

Given his activism and public profile, it seems appropriate to show his LinkedIn here that shows his background, which seems pretty extensive.

hey Charles,

yupp, i did share this post on my instagram story, and invited folk who have experience/opinions (positive or negative) on the Pledge to contribute. it seems to me that people who have direct experience with the Pledge and/or have spent considerable time thinking about it prior to this post could contribute worthwhile comments to the discussion 👍

hey Larks. thanks for that analysis.

is it not a positive outcome that this post is drawing new members to the EA Forum and community?

I do think it is good to have the EA forum as a place of discussion and disagreement on how to improve the world.

I think my critique would be different from the ones described above. It would be that convincing people to go vegan (the end goal) takes time for them to interiorize the reasons and agree. It is naive to believe that we are Bayesian beings that have their preferences written in stone, and so if I make a really smart argument they will just change.

Rather, I believe it is more effective to invite them to try out things such as Meatless Monday, Veganuary, or similar. My intuition is that the key is showing that it's not so costly to change (it really isn't).