By Martin (Econ PhD) and Yonatan (reads some Econ stuff online sometimes)

| This is a Draft Amnesty Day draft. That means it’s not polished, it’s probably not up to my standards, the ideas are not thought out, and I haven’t checked everything. I was explicitly encouraged to post something unfinished! |

| Commenting and feedback guidelines: I’m going with the default — please be nice. But constructive feedback is appreciated; please let me know what you think is wrong. Feedback on the structure of the argument is also appreciated. |

TL;DR:

- Improving economic literacy with voters could be a cost effective way to improve policy decisions.

- Israel is an interesting case study - a few bloggers are managing to (from Yonatan's subjective point of view) influence voters and policy.

- This intervention is really cheap: I doubt the spending is over $200k per year for all orgs and people working on this, combined.

- I don’t pretend to prove anything (I didn’t run an RCT between [Israel with these bloggers and orgs] and [Israel without these bloggers and orgs]), but I do hope to pitch “this is interesting, I hope someone will look deeper into it, the potential leverage here is too big to ignore”

- Does this seem interesting enough to look more into?

An example

Just after posting I saw the tweet below. It's a good example of a relatively complicated thing that is being communicated by these bloggers and I think is well worth it:

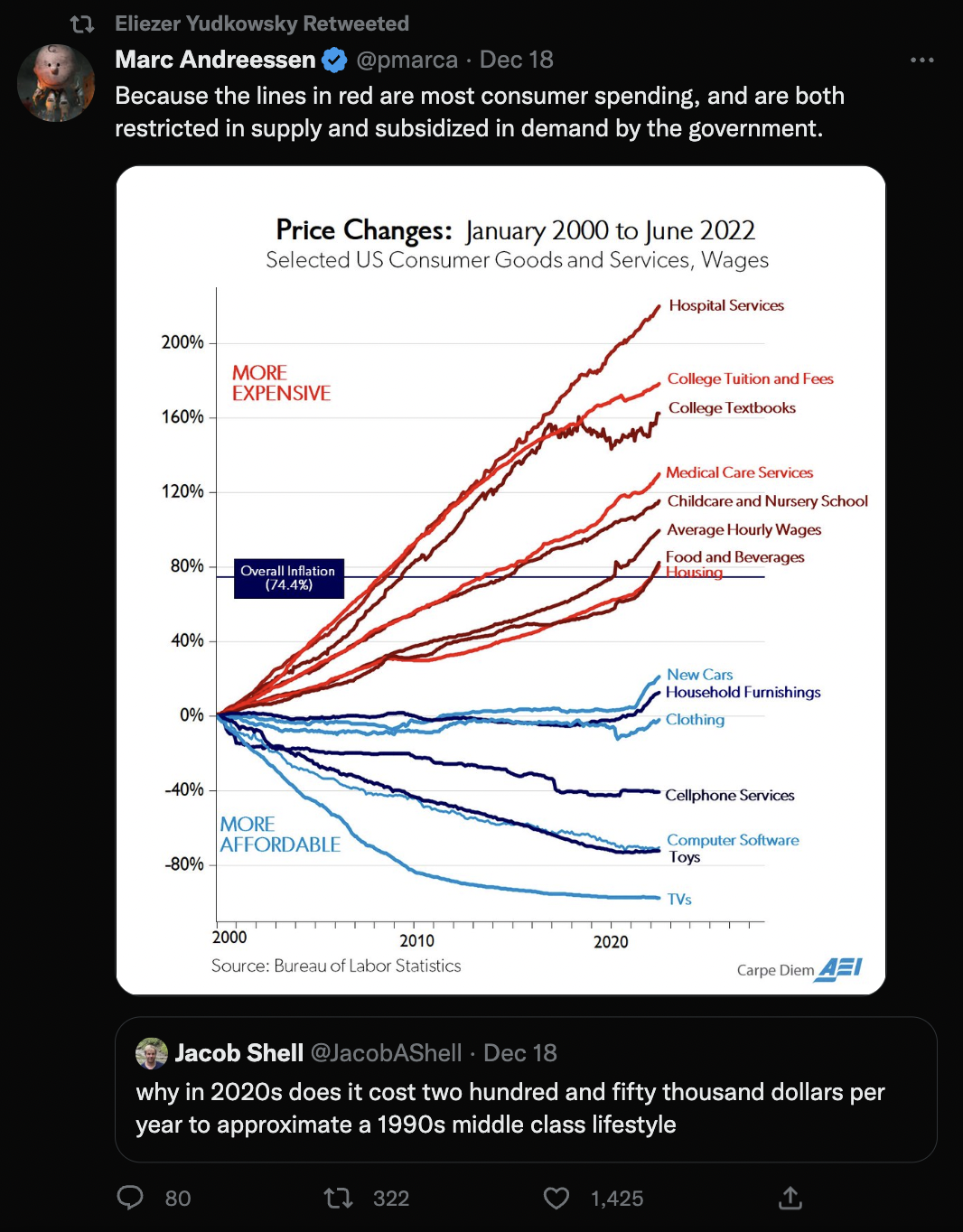

For people listening to this post: The tweet shows the prices of various products over time. Products shown to get more expensive "are both restricted in supply and subsidized in demand by the government".

Edit: Maybe this tweet isn't so good, see this comment

Longer version

Don't forget to practice Effective Skipping! If a title doesn't seem interesting, skip it!

This seems to work in Israel (and so I think it's not impossible to do)

TODO: This would be the main section of the post, listing out what I see as successes of the ECON bloggers in the last years, which I didn't get around to collecting, and so I never posted this.

The overview would include:

- Making it cheap to import products, including "basic" food, which would give customers cheap quality things to buy instead of protecting local manufacturers.

- Saving money for the government ( = the tax payers) by allowing it to buy cheap quality products like asphalt and busses (instead of agreeing to pay certain companies a lot more for the same quality product).

- Reduce cost of doing business, for example by allowing producers to have EU or US approval of product safety, instead of having Israel-specific standards (for example, safety standards for pampers).

Sorry I don't have a tidy list of achievements. If this post gets interest, this seems like the main thing to add.

Why I think changing economic policy a good idea in theory?

- It's high leverage.

- Bad economic policy decisions are a tragedy of the commons: it doesn't hurt any one actor enough for it to be worthwhile to fight back. In other words, there's no way to make a billion dollars from managing to save the economy 100 billion dollars, and so (almost) nobody even tries.

Does this interact with other cause areas?

Climate change

It could be efficiently addressed with carbon taxes. The main bottleneck for carbon taxes is voters not liking them. Teaching Econ 101 would address that.

Global health and wellbeing

If a country has problems caused by poverty, one great solution could be - make it more rich.

Spreading the EA "mindset"

Thinking like an economist and thinking like an EA are things that overlap. I’d be very happy if the public would think a bit more in EA terms.

Reasons for EA not to try this intervention

- It touches on politics, there are downsides in making EA political.

- It's high variance.

- There's a long feedback loop between action and policy change.

- It's helping a 1st world country

- (though I think the cost effectiveness is so high that it might be worth it anyway. Does anyone have estimates for how cost effective it would have to be?)

- Will this transfer well to other countries? I don't know

Does this seem worth looking into?

Here are some questions that come to mind when I consider whether this is a suitable cause for EA:

- If the cost effectiveness is $1 spent to $10,000 saved around the country, is that good enough? If not, what's the cutoff?

- How would you measure this?

- By the success so far?

- By the potential?

- By vetting (or funding) a specific more measurable part? (there are smaller interventions here, like allowing employees of a company to chose not to be unionized if they don't want to, I can elaborate. Israel has some strange laws around unions)

- If this works, is it worth trying to do in another country?

- (Is the new Israeli government going to undo all the good economic policy that was done by the previous government?)

Remember this is super drafty!

But I took the nudge to post even though I still have missing sections here.

AMA

I'm all for this, though I've got a dog in the fight: I'm ED of PolicyEngine, a nonprofit that largely intends to improve epistemics around economic policymaking by making epistemic tech available to everyone. Our free, open source software estimates households' taxes and benefit eligibility, and lets users design customizable policy reforms and estimate impacts on society and households.

Since you mentioned a carbon tax, our new app beta.policyengine.org, which we'll launch in January, lets you design a custom carbon tax in the UK. Here's a 2-minute video on how to do that and pair the carbon tax with a dividend, or the link directly to the policy. For example, we estimate that a budget neutral £100/ton carbon dividend would benefit 2/3 of UK residents and lower the poverty rate by 7%. We also model much of the US tax-benefit system, though we currently only model carbon taxes in the UK (here's how).

We'd be excited about building PolicyEngine into an educational initiative, especially with EAs. We've also started working on an EA Forum post for a shallow dive cost-effectiveness of computational policy simulation--I think this plays well into our community's embrace of forecasting as well. Happy to chat more with folks on this.

My (fairly uninformed) impression is that Israel is somewhat unique in that economic policy is not a major axis of differentiation between the main political parties. It might therefore be much easier for bloggers/commentators to influence economic policy because it is not very politicized. Would you disagree with that impression?

I agree, I only endorse this ideas in countries like Israel where, as you said, economic policy is not a major axis of differentiation.

I'm a big fan of increasing economic and social scientific literacy in general, but I think using the Andreesen tweet as an example weakens you case significantly. The tweet that you linked to isn't from an economist or from whay I can tell a blogger at the moment, and the tweet itself seems to me to do less for economic literacy than it does to increase it: its a claim with nothing backing up its, no information about the actual context or economic theories its rooted in, and no policy recommendation. It takes a very complex issue and both reduces it and flattens it with no explanation or nuance, offering very little understanding to someone who isn't already economically literate. It's also a good example of why economic literacy alone is shortsighted, in that it implies that the problem with healthcare or childcare in the US is that the government regulates and subsidizes too much, which is not at all a straightforward or necessarily true claim. Healthcare in particular is generally recognized (including by the entire field of healthcare economics) as a field where free market theories fundamentally don't function well, for a number of reasons. Housing could definitely do with less strict zoning regulations, but regulations on building standards are absolutely necessary and life saving, as are regulations for healthcare provision and child care standards. These are also, for the most part, vital services that, unlike some of the blue lines, you cannot love without or do with less of, and that will have potentially devastating consequences if they are offered at substandard quality. All these different considerations are erased.

This points to a couple significant issues around using things like blogs to increase economic literacy: on the one hand, people who aren't already somewhat invested in learning about it won't be willing to read nuanced, useful explanations, and on the other hand short, pithy posts like the Andreesen tweet can do more harm than good by providing overly simplistic, cut and dry answers that arent necessarily true but that spread easily to complex and nuanced questions.

(I was originally going to add this reply to my own comment, but I think it works better here)

You say:

But many countries already have a carbon tax and what actually happens is that while their production based emissions go down, their consumption based emissions don't go down nearly as much (because other countries manufacturing industries will become polluters for them). These countries still pollute a lot despite these taxes. What might alleviate this is tariffs on polluting goods, but economists are against tariffs. As wikipedia says:

Taxes seem too little too late at this point, and I think much more radical actions should be considered.

You say:

This won't necessarily make wellbeing rise since the increase in riches might not be evenly distributed. If Kim Jong-Un makes a billion dollars tomorrow North Korea's GDP will rise, but I don't expect the wellbeing of the average North Korean to rise too. Orthodox economists tend to be very concerned with 'growing the pie', but less so with how that pie is distributed.

______

I think there are a few fields which actually have the potential to be harmful if you only learn a little bit about them. A little bit of behavioral economics might lead someone to dismiss other worldviews if they find evidence of bias in its adherence. A bit of metaphysics might leave you horribly confused/with the impression that metaphysics is itself confused as a field. And a little bit of psychiatry might make someone conclude too quickly that they have figured people out.

I think economics is also a field that has the potential to be harmful if you only learn a little bit (and I don't think other social sciences like sociology and public health suffer from this).

Take for example GDP, if you only learn a little bit about economics you might not realize how many subjective/ideological judgement calls are made about what counts as contributing to GDP (should e.g finance be subtracted, ignored or added to GDP?). The fact that environmental impact is not important to GDP should already be seen as a red flag for the entire concept of measuring a countries wellbeing through the lens of GDP.

Or take supply and demand. The standard supply and demand model will tell you that having/increasing the minimum wage will increase unemployment. But if we look at actual empirical evidence it shows us that it doesn't. Learning the basics of economics might mislead people about which policies will actually help people.

Hey! I sent this to Martin (the econ PhD) since you're replying mostly to his opinions, I just wanted to leave a quick comment saying that your comment was seen and appreciated (which I assume you prefer over waiting for when he'll be available to reply)

Thanks!

I'm aware that emission trading and carbon taxes could be higher and that this will help with production based emissions. All I'm saying is that without tariffs you give countries an incentive to become heavy polluters and free-ride on other countries climate efforts, all the while consumers import from said polluting countries because their products are cheaper.

Also, I think that a lot of market based solutions could have worked if we started immediately when climate change came to light, but given that companies successfully delayed action and we're now already taking damage, it becomes much more prudent to consider non-tax based solutions. EA's and orthodox economists tend to be dismissive of ideas like degrowth, but I think the case for degrowth is much stronger than it's given credit for (although I don't know whether Martin is against degrowth so I'm not going to make any arguments until he disagrees).

I would also be interested in hearing Martin's thoughts on economics isolationist tendency that I outlined in my other comment.

Hey, just a short reply that the tweet was picked by me (the "read some econ online" person), not Martin (the econ PhD person).

My own attempt was to be more clear on what I'm trying to convey in blogging instead of being very vague.

Good examples of what I want are:

This might seem overly obvious (?) but in Israel (where I live, and which inspired this post), there are constantly regulations that ignore these facts, and I think most of the population doesn't understand them.

My hot take (which you might totally disagree with) is that the population doesn't learn well from long references with source data. they (we) learn better from 100 examples such as "here's a regulation they're considering putting into place which limits prices, they say it will make the product more accessible, but in theory it will also limit supply and so I expect shortages. let's see what will happen" --> ... 3 months later "ok we have shortages now".

The bloggers I'm talking about are economists themselves (one is a professor, one is a student but regularly gets public compliments from professor-like people). They understand the theory but they present it in a more accessible way to non academics (like me).

I also want to acknowledge:

I feel like you might be overestimating the role of economic literacy in this dynamic. I can't speak to how well the public understands them, obviously, although I honestly find it hard to believe that most people don't at least understand 1 and 2 intuitively. More importantly, I'm very skeptical that the regulators are simply ignoring these "facts[1]". They are most likely making tradeoffs for different priorities than just trying to make something cheaper. You mention things like safety standards and protecting local manufacturers in your post, these are a good example of where other factors enter into the equation. They're also a good example of how having a perfunctory understanding of the basics of economic theory fall very short for actually understanding economic policy.

One very anecdotal and simplified example for what I mean is that where I grew up, the government heavily deregulated and opened up the construction sector from the 80s onward to make home ownership easier and cheaper and to grow the economy. The deregulation and the speed of new construction (plus some good old style corruption) made it much harder to keep up with necessary safety standards, and a large earthquake in the 90s ended up with tens of thousands of people dying and hundreds of thousands of buildings being rendered uninhabitable. People who were previously homeowners lived in tents for months and even years until enough (heavily government subsidized) houses were built to rehome people after the disaster.

So yes, while regulations slow down and limit the provision of certain services and needs, and can make it much more expensive, not having regulations can also come with heavy costs. A lot of policymaking is about figuring out the sweet spot where the trade offs are acceptable. I'm sure you're already aware of all of this, I'm just trying to explain why I don't think the oversimplified economic literacy (or lack thereof) that you seem to be advocating for doesn't seem very helpful or meaningful to me, both for understanding current policy landscapes and for influencing them.

I don't disagree with this on pedagogic level, but I do think that it's ultimately not practical at all. Amassing that kind of volume of examples is extremely time and effort intensive for the blogger, and keeping track of it is the same for the reader, and it seems like it's very much not worth it for an outcome that is basically "oh look this one economic theory principle seems to function in reality". I don't see how you could actually give anyone a strong enough foundation of economic literacy to be useful using this method.

Honestly, I don't even know what "sides" you're referring to here so you're probably fine?

This is actually indicative of the point I'm trying to make in regards to the utility of this type of blogging: reading it doesn't give you an idea if it makes sense overall or has some complicated background (and pretty much all things in the domain of economic policy do have a very complicated background), but it seems like a clear and useful piece of knowledge at first glance so it's easy to file it away in your brain as a way to judge policy proposals, despite it being at best extremely open to debate on many levels.

Even the very simple points you list as things you want to get across are a lot messier and more complicated in reality, and they depend very strongly on their context. For example, it's quite possible that a very tight housing market won't see a drop in prices from added housing stock until there's a severe surplus, because you have distortions in the market like big investment firms being able to buy a large portion of the available stock at higher prices than everyday consumers as investment properties to rent out, and housing is such a fundamental necessity that people can't or won't forego it without having absolutely no other option, so very high rents are a possibility in a way overpriced televisions aren't.

Ah, if regulators were trying to get some tradeoff (for something like "safety" and not something like "get elected" / "corruption" / something like that), then I would change my mind very significantly.

For example, in Israel (citations: all of these are from memory, sorry if I'm a bit mistaken, but I think the main direction is correct and I can look them up if important):

I can go on and on with this, and I wish I had some list ready.

My point is that I think there are many cases where the government is not balancing some interest like "safety", it is simply something between "wrong" and "corrupt", and the way the gov pulls this off is partly because the public doesn't consider things like "there is a cost to protecting a specific Israeli pamper maker, and these costs add up, and it is negative sum".

Maybe I'd accept it if the only people who'd vote for protecting the Israeli pamper maker were stakeholders in the pamper company, but that's not the situation, they get widespread support, "Israelies wanting to help each other" or something (but in a way that is negative sum way by mistake).

Also,

I don't think the politicians are blind to this. Specifically our long time prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was 10+ years ago in charge of the treasury, and did a really good job, reducing regulation and making the economic situation much better. I'm no expert, but I personally assume he understands economics very well. But he has a lot of pressure to satisfy various pressure groups (like paying some people to.. not produce eggs.. in order to keep prices HIGH enough to protect the egg industry, which somehow is supposed to be good for the consumers).

I'm not justifying his actions, but I am trying to say that "politicians understanding" is not enough if the population totally does not.

Also,

I accept that in some situations regulation is good, definitely.

And some situations are complicated.

But many situations are not complicated. Some situations are just protectionism and corruption and negative sum games.

[my tone here is ranting because I'm mad at the Israeli public, but at the same time I'm aware that I'm no expert and you might correct me everywhere]

I truly and deeply feel you on that - this is all extremely frustrating and I've had to live with more than my fair share of terrible politics and politicians.

Yeah, both corruption and tradeoffs for goals of election/reelection [1]definitely do come into this - I was focused on the ignorance aspect and didn't touch on the malfeasance aspect, but it is definitely very real.

I certainly see your point, but I want to point out that the "negative net" here isn't necessarily as self-evident as you seem to think it is. Politics are messy and economic policy isn't only about pure economics - the costs of "Israelis wanting to help each other" could very well be acceptable and even necessary to someone who prioritizes nationalist sentiments.

I don't want to comment on your examples in specific, because I don't really know the relevant policy and political context in detail, although I will say that I'm not sure I find them convincing as examples of "the government is acting corruptly/just wrong, and people don't get it because they lack economic literacy". In particular, 1,3 and 4 seem like they are actually very much related to not only corruption but specifically regulatory capture or just straight up institutional breakdown. The egg industry being heavily regulated but extremely unsafe is a sign that the regulatory institution isn't doing it's job, for some reason or other - corruption, collusion, capture, being underfunded or underpowered (and these can certainly coexist with a strong regulatory framework). I completely agree that the war argument in number 2 is bonkers, but it points to more of a lack of critical thinking in general than a lack of economic literacy - basic economic literacy won't tell you that your oil is being imported and farming needs fuel and ergo even if you have strong local agriculture industries, they can't be independent in war times. But I am also fairly confident in assuming that this claim isn't the entire backbone of protecting local economies and industries - "protecting the local economy " tends to be tied up in a lot of political and affective ideas about right and wrong and national identity, and just the everyday anxieties around financial health, employment and sustaining one's life in a capitalist society.

I'm not at all trying to argue that politicians are always good and wise, and that all regulation is good, and that people are generally smart enough to not have to learn things - quite the contrary, I think that a lot of these systems are fundamentally broken and I've never once in my life voted for someone I actually trust, let alone truly like. What I'm saying is that these are all very complex things - even the examples you seem to write off as just bad or clearly wrong. People have a lot of competing interests and priorities when it comes to voting, and something that doesn't make sense from an econ theory homo economicus POV can be accepted and supported broadly simply because people don't really function that way - they might care more about nationalism or supporting compatriots (I personally know a lot of people who would rather pay more for lower qualities products just because it's "home grown" and they have very strong national identification). I also don't think that the enitre reason people can't flag these examples of corruption as corruption isn't that they lack economic literacy. Things like disinterest, lack of knowledge about these policies, high trust in the government and institutions etc. all play a role in this. I don't think that economic literacy alone is a huge enough factor in a lot of political choices and attitudes, and I don't think that a simplified economic literacy will be helpful in rectifying these problems. I personally don't really think that there's much meaningful difference between the kind of "knowledge" you get about policies from your intuition and experience and from just following political debates in media and an economic literacy that is simplified to "Raising prices causes people to buy less. Reducing prices causes people to buy more./Limiting supply means there will be less to buy (even if prices are low)/Limiting prices (too much) causes less production, and so there's less supply", for example, in being able to understand policies. For economic literacy to be meaningful in understanding policies and politics, it needs to be much more in depth and complex, and give a good idea of the economic and non-economic context of the issue.

I have a migraine coming on and I think I'm rambling because of it, sorry about that. To put it in a tidy summary, I'd say that the reason I don't think the type of economic literacy teaching you seem to be advocating for is helpful is because it's simply too simplistic - it doesn't really give people the knowledge or reasoning skills they need to navigate these very complex issues, and it tends to boil down very disparate problems down into some kind of amorphous blob like "regulation bad, free market good" or "regulation good, free market bad" to make it legible and shareable. I don't really think this will accomplish the admirable goal you have of either meaningfully raising economic literacy or leveraging that economic literacy for better policy and political outcomes simply because it's insufficient for that task.

I do want to say that making trade offs for reelection is, I think, a lot more complicated than something like corruption - there are a few ways to look at this. One is that it's a self-serving act in the pursuit of power, and it thus a Bad Thing. Another is a more populist approach - if you do thing to get elected and thing gets you elected, that could be considered a manifestation or reflection that thing is actually want the people wants, and even if it isn't in their best interest from your vantage point, democracy is the right of the people to make choices for themselves, even if they have to pay a price for it. Most importantly, in my opinion, you can also think of it as a calculated tradeoff with good intentions - if you think thing A is more important to do than thing B, but you need to get reelected or even just elected to do thing A and sacrificing what you think is the morally correct thing to on thing B is necessary for that, that can be considered an unfortunate but necessary trade off, and it's one that we see happen a lot in real life. Politicians don't run or get elected on a single policy choice, and a lot of the work of policy making involves making concessions and compromises to attain some kind of "greater good", even if an isolated policy choice made in that pursuit is undesirable or harmful. I don't want to say that this is always good or acceptable or reasonable - it most certainly isn't. But I do think that there is a lot more room for nuance when it comes to trade offs for election than there is for tradeoffs for corruption.

There's a vast difference between the policy changes you list as having happened and those that would be related to the tweet you quoted. I'm strongly against funding advocacy for the latter (which shouldn't come as a surprise as I'm a socialist).

I also don't think economic bloggers had anything to do with these policy changes. What makes you think they did?

I'd like to add that related interventions have been successful for policymakers in the developing world, with econometrics training increasing reliance on RCT evidence in policymaking and instruction in Effective Altruism increasing politicians' altruism. Indeed, influencing policymakers may be cost-effective in a wider range of scenarios as it could be far cheaper and is unlikely to require as much highly visible political messaging.

Any reason you think we should focus on economics in particular and not other social sciences like e.g sociology or public health? Or even a combination of different sciences?

Mainly because I saw this working (and because I think it's important)

I'm not saying the others aren't important - I'm just not hurrying to generalize, I think there's still uncertainty even for doing this more for Econ and moving to another topic will add more uncertainty

(but I'm not against)

I think that if we want to make people more like EA's we have the most evidence that teaching them the field of philosophy yields the highest results.

Here is a post about it, but TLDR we have lots of studies that find it contributes to cognitive development and moral development.

Philosophy is also much more tightly integrated with other social studies like law, political science, history, sociology, gender studies... which in turn all make a lot of attempts to integrate themselves with all the other social sciences. This makes it so that learning about one discipline also teaches you about the other disciplines. Economics meanwhile doesn't associate itself with the other disciplines that much. Economists have a tendency to see their discipline as better than the others starting papers with things like:

In the paper "The Superiority of Economists" by Fourcade et al, economists were found to be the only group that thought interdisciplinary research was worse than research from a singular field. Furthermore they looked at top papers from political science, economics and sociology. They found that political science and sociology cited economics papers many times more than the other way around:

This lack of citing other social sciences was later confirmed by Angrist et al (though to be fair, it is getting better and psychology is even worse):

Given the complex interdisciplinary nature of societal issues (and the problem that teaching people a little bit of economics might make things worse as I outlined in my other comment) it seems logical to conclude that other social studies might be better suited, and we have a lot of empirical evidence for the effectiveness of philosophy.

Interesting!

A good example of the blogging I'm in favor of, especially when it comes together with a current policy proposal that is trying to move a line from blue to red, and having the population thinking this would be very nice of the government:

Edit: Added this to the post

I think this tweet is the opposite of "economic literacy" and/or "EA mindset". It poses a link between regulation and increasing prices without giving any justifications, weighing alternatives, thinking about any counterfactual, etc.

TL;DR: Yeah, this tweet doesn't in itself explain everything.

It's better, for example, to show a suggested regulation (like with butter imports in Israel), and say what's expected to happen if it passes, and then if it passes - to reference the previous post and say "yeah this isn't surprising"

Do that 1000 times and a pattern emerges

I wonder if mass economic literacy is less important than a few elites and institutions who have leverage over a nation's economic decision making. Are there more significant structural reforms that would be more impactful rather than merely "electing better"?

Not sure what kind of reform would drive a policy like cap and trade (but I also think there are economically cogent arguments against cap and trade).