This is a linkpost for https://ourworldindata.org/longtermism

Hi everyone! I'm Max Roser from Our World in Data.

I wanted to share an article with you that I published this week: The Future is Vast: Longtermism’s perspective on humanity’s past, present, and future.

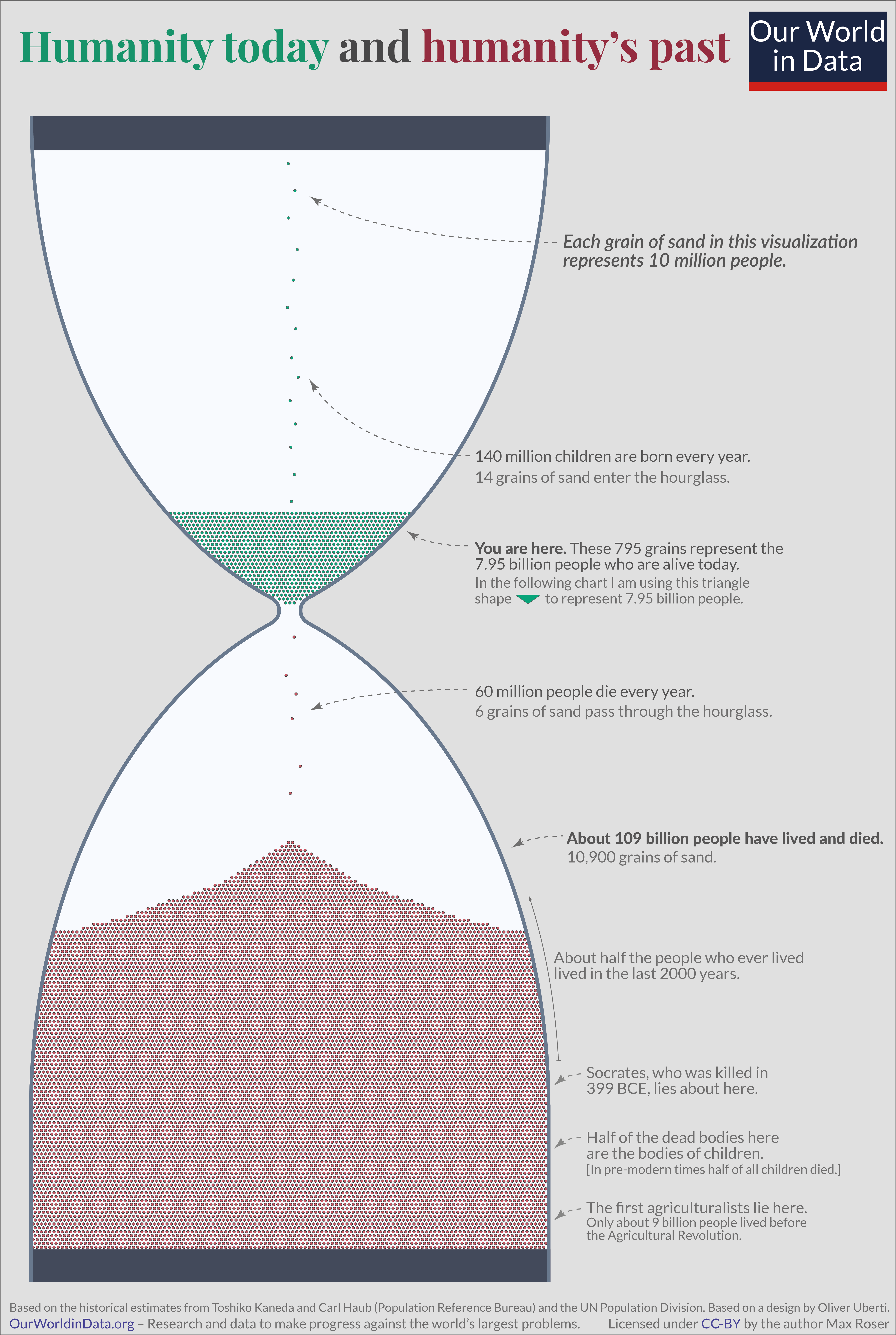

In it I try to convey some of the key ideas of longtermism in an accessible way—especially through visualizations like the ones below.

I hope it makes these ideas more widely known and gets many more people interested in thinking what we can do now to make the long-term future much better.

We have written about some related topics for a long time (in particular war, nuclear war, infectious diseases, and climate change), but overall we want to do more work that is helpful for longtermists and those who work on the reduction of catastrophic & existential risks. To link to one example, I recently wrote this about the risk from nuclear weapons.

My colleagues Charlie Giattino and Edouard Mathieu are starting to work on visualizing data related to AI (e.g., this chart on AI training compute).

Charlie, Ed, and I are sharing this here because we'd love to hear your thoughts about our work. We're always interested to hear your ideas for how OWID can be helpful for those interested in longtermism and effective altruism (here is Ed's earlier question on this forum).

I assume this is redundant but I might as well check. Have you considered applying for FTX for funding to run the project which is modelled after your project already? Seems kind of a no brainer to avoid replication and use your tech/branding to deliver this, though I'm sure there are things I don't understand.

Thank you so much for doing this. I like the push to establish Longtermism as something outside of EA which I guess this is part of.

I have a lot of respect for your work and find your non-partisan, numbers-focused approach really useful when discussing things with people.

I really enjoyed the article. A well-written, short introduction and great (as usual) visualisations which will likely see widespread use for conveying the scope of our future.

Personally, I didn't find the 17m * 4600km beach analogy for 625 quadrillion people super intuitive, and yes, I know, such numbers are basically never intuitive. A framing I found a bit easier to grasp compared the total possible number of humans to seconds in a whole year and said that the number of humans so far equals only a few seconds after midnight on new year or something. But that's just a tiny personal preference, you probably thought about such analogies a lot more.

Thanks for clearly presenting numbers and topics that are more difficult to convey, it's great!

I was really struggling to find a way to make this work. I should have asked you earlier! Time could be a very nice way to illustrate that.

It would also work nicely with the metaphor of the earlier illustration in the post, the hour glass.

But I'm not sure it works nicely when I put numbers on it:

1 year are (60*60*24*365)=31,536,000 seconds

The point estimate for this year's global population is 7,953,952,577

So if 1 person equals 1 second then today's world population would be 7,953,952,577 /31,536,000=252.2 years.

And 625 quadrillion seconds are 625,000,000,000,000,000/31,536,000= 19,818,619,989.9 years. Almost 20 billion years. Way older than the Universe.

The numbers are so large that it is hard to make it work, no?

Making the time unit smaller would be another way to make this work.

Just for the sake of it:

One second is equal to 1,000,000,000 nanoseconds. One billion people are represented by each tick of a second.

So today's population are 7,953,952,577 /1,000,000,000=7.95 seconds.

1 year are (1,000,000,000*60*60*24*365)=31,536,000,000,000,000 nanoseconds.

This means the future population is represented by 625,000,000,000,000,000/31,536,000,000,000,000=19.8 years

So, if we go with the 1 person = 1 nanosecond illustration then today's world population is represented by 8 seconds and this future population would in contrast be 19.8 years.

That feels definitely more intuitive than the 1person=1second illustration, but it has the downside that no one has an intution of nanoseconds I guess.

–

What do you think? I like your idea of using time, but I find it hard to imagine 20 billion years and I also find it hard to have an intuition of nanoseconds (but maybe 1 billion people=1 second works).

Thanks for the idea! I'm not sure what I'm going to do, but it was fun to explore these numbers in this way.

Do you have another creative idea for how we could make this illustration work?

i think if the comparison you’re interested in is that between today’s population and the future population, it doesn’t really matter whether the thing representing 1 person is intuitive or not, so long as the things representing the two compared populations are intuitive.

Thanks for doing the calculations! I agree, not straightforward. But like Erich said, it was not about representing a single human. It was imagining humanity's "progress bar" (from first human to final, 600 quadrillionth human in a billion years) as one year. And humanity today being only 8 seconds or so into that year-long progress bar. The idea being that framing progress as seconds in a year is more intuitive than saying 0.0[...]01 %.

You could have a big clock and it could be just after midnight. Then there could be a cut away for the bit just after midnight saying "this is the time of all the humans that have every lived" with it cut up.

THen the rest could be coloured saying "this is all the future time of a conservative estimate of humans to live".

Something like this, though I think it's pretty messy. A big clock face for the first hour and then others for the next 23

I loved this article! and have used it to explain my interests to family who aren't familiar/emotionally connected with longtermism. I also frequently used OWiD pieces (e.g. health + climate) when working in the FCDO - it became IMO the most credible and impartial source for providing new ideas & information to us, and I think OWiD can achieve this for longtermism-related data.

I wondered if it is possible to add a visualisation of a short animation: first, of the hourglass representing past and present (10 millions of) people, then zooming out to have a third section of the hourglass at the top, representing the future-people dripping in to the present-people section. For me, this would be a more emotive visualisation of (a) the scale and (b) how connected we are to future people, than the existing two visualisations.

This was fantastic, thanks for sharing!

I think there're a lot of inferential steps most people would need to go through to get from their current worldview, to a longtermist worldview. But I think a pretty massive one is just getting people to appreciate how big the future could be, and I think this post does a great job of that.

An added bonus is that the idea that the future could be huge is a claim the longtermist community is particularly certain of (whereas other important ideas, such as the likelihood of various existential risks and what we can do about them are extremely uncertain and contested). While quantifying how big the future could be, or is on expectation, is really difficult -- but the idea that it could be extremely big stands up to scrutiny quite well. I think it's really useful to have such beautifully illustrated graphs that put where humanity is now into context, I'm excited to use them for future work on longtermism at Giving What We Can.

RE something that would be useful for OWID on longtermism. I'd be very interested in approximate data on the amount of funding each year that gets directed to improving the very long-term future. Given there'd be a lot of difficult edge-cases here (e.g., should climate change funding be included?), it may need to be operationalised quite narrowly (perhaps "How much money do we spend each year on avoiding human extinction?" would be better.)

Thanks. Very good to hear!

Yes, the question about tracking funding is one that is on our list – it'd be so helpful to understand this. But building and maintaining this would be quite a major undertaking. To do it well we'd need someone who can dedicate a lot of time and energy to it. And we are still a very small team, so realistically we won't be able to do that in the next few years.

Makes sense! From your appearance on the 80,000 Hours podcast, I was shocked by how much you have managed to do given you're such a small team. I'm really looking forward to seeing what you accomplish as you expand :)

Customisable longtermist graph.

While I like the hourglass graph, I think it's possible that it underestimates the amount of conscious time that may yet be able to be lived. Is it worth having a diagram where people can put in their assumptions (number of concurrent human equivalent lives, length consciousness will be around) and have it generate a graph based on that?

I like that idea! I'd be happy to find $5k in retroactive funding for someone who makes a nice version of this (where what counts as 'nice' is judged by me). I'd also be happy to discuss upfront funding (including for larger amounts if it turns out that I'm miscalibrated about the amount of required work) – DM me if you're interested or know someone who may be a good fit for producing such an interactive graph.

You forgot to add one of my favorite infographics! ;)

I've been a big fan of your work for many years now, and I'm really glad you're taking a stab at explaining Longtermism! I remember being in school many years ago, before the EA movement was a thing, and trying to explain my intuitions around Longtermism to others and finding it difficult to communicate. I feel like we really need some introductory material which is helpful for building intuitions for a target of something like 4th grade reading level, to be approachable by a wider audience and by kids.

How did you make that graph? A Python library? It looks really nice!