An argument against saving lives

When making the argument for charitable giving, a response I have often received is that saving lives in areas that are already over-populated will perpetuate over-population-solving nothing. It’s a concern I shared when first considered charity.

The logic seems sound on the face of it. For instance, if a predator is eliminated from, let’s say, a rabbit habitat, the rabbits can become over-populated until they reach some other natural limit, like resource depletion. This is the standard Malthusian theory of population equilibration*.

An argument for saving lives

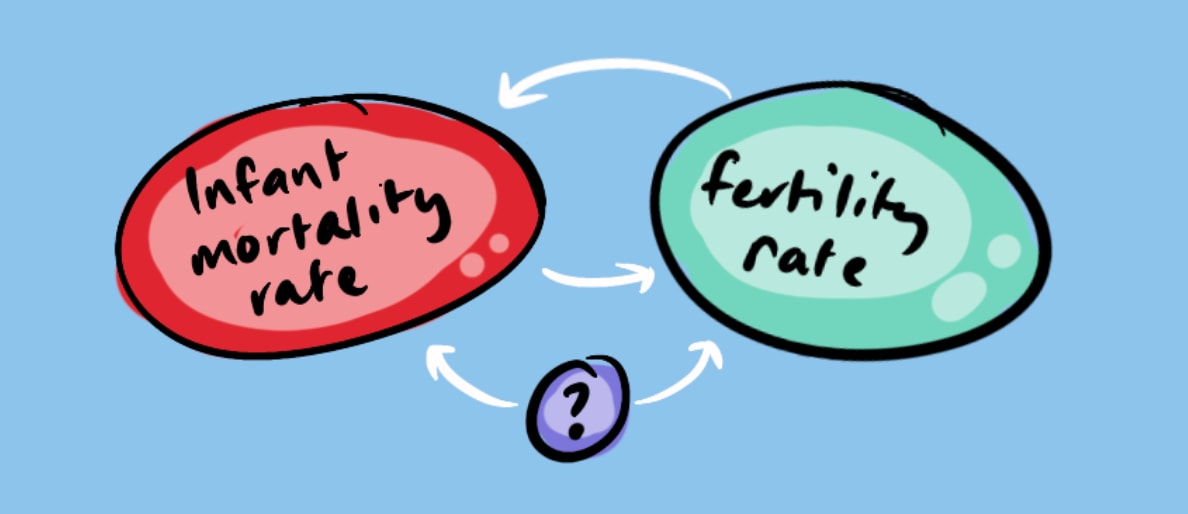

I will be making the case that the reverse situation is actually at play, and that, somewhat counter-intuitively, by saving lives we actually reduce over-population. I will be employing two studies; one looking at data from the US and the other looking at data from Europe. The first conclusive finding is a clear positive correlation between the fertility rate and the infant mortality rate over time.

“In every case, changes in infant mortality are positively associated with changes in fertility and most are significant.” (European study)

This correlation is not just evident over time but is clear geographically.

More infants dying means more babies being born. But correlation is not causation! It is entirely possible that any or all of the following relationships are at play.

2. A Higher Infant Mortality Rate causes a Higher Fertility Rate

3. Both Fertility and Infant Mortality are affected by other variables

The case I am making depends on option 2 being a factor.

If this is the case, then saving lives reduces over-population-creating a win-win situation where the population becomes more sustainable alongside the obvious benefits to individuals, whose lives are saved in the process. But why would this be? Let’s unpack the issue.

Why examine fertility and infant mortality?

In short, for the sake of clarity.

It’s important to clarify that the fertility rate is not actually a measure of how fertile individuals are, but rather the average number of children an average woman gives birth to. It’s essentially the ‘birth rate’ but relative to the female population only, which gives a clearer signal regarding reproductive behavior. Infant mortality turns out to be a clearer indicator of societal health, and has a clearer correlation with reproductive behavior (than other candidates like ‘life expectancy’).

So, we know that there is a correlation between fertility rate and infant mortality, but why is this? First let’s start with the obvious.

1. High fertility leads to increased infant mortality

If we look at option 1 in the earlier list, it is understandable that there is a causal relationship where the more children someone has, the more likely one of those children is to die. It’s easy to imagine that in a society where the norm was to have 50 children each, many more children would die due to exhausted resources and, necessarily, parental neglect-reaching a Malthusian equilibrium (involving a lot of death).

Families have a limited carrying capacity for children, and so greater fertility will lead to greater infant mortality. But does carrying capacity explain the entire correlation? What about the fact that wealthier families tend to have less children? Surely if carrying capacity was the only issue, wealthier families would have more children, due to a higher carrying capacity. This suggests that a option 1 is not the only causal factor.

2. Elevated infant mortality rates result in higher fertility

What is hoarding?

Due to patchy data up to 1850, the US Study researchers initially found no correlation between fertility rates and infant mortality rates until they looked at the period between 1850 and 1940, where they found an indication of ‘hoarding’.

“… there is evidence that birth rates responded to changes in death rates by the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Furthermore, the relationship strengthened over the early part of the twentieth century as the decline in infant mortality proceeded rapidly. There is also a suggestion of a lagged response of fertility to mortality change, indicating hoarding (or insurance) behavior.” (US Study)

What is hoarding?

Hoarding is the practice of having more children, in an environment with a high risk of infant mortality, to ensure some children survive. But how do we know hoarding is going on?

Both studies use instrumental variable techniques to isolate the causal effect of child mortality on fertility, allowing them to account for how much of the correlation is determined by other factors like hoarding. If we look at the results of the US Study we find…

- Direct replacement effects are about 10–30%.

- Gross replacement effects, which include hoarding, are much higher, in the range of 60–80%.

Direct replacement effects are what we would expect in a scenario where the causality is simply from fertility to mortality. Gross replacement effects explain the additional births beyond what would be expected from direct replacement alone. It is likely these additional births are a response to high infant mortality, indicating parents are having extra children as a buffer against the loss of infants (hoarding).

Both studies agreed that Infant Mortality had a causal effect on Fertility.

“… there are important issues of causality that must be resolved before drawing conclusions. The few studies that attempted to disentangle the direction of causality using instrumental variables estimation found, as we did, that important causality was operating in both directions.” (US Study)

The European study concluded…

“… there is substantial evidence that mortality decline was an important cause of fertility decline in Europe.” (European Study)

3. Additional factors influence both infant mortality and fertility rates

There is always the possibility that other unknown factors might affect both Infant Mortality and Fertility, as the European study clarifies.

“… we cannot completely rule out the possibility that the estimated associations of fertility and mortality, even when using instrumental variables and fixed-effects methods, actually reflect a spurious association induced by unobserved variables that influence both fertility and mortality and that change over time. These variables might include breastfeeding, health conditions, nutrition, or unobserved aspects of economic development and modernization.” (European Study)

While this is an important consideration that cannot be dismissed, it does not contradict the imperative to seek to save lives through charity. This is because, not only do life-saving charities save lives, they do so through improving the very factors noted above that might be involved in the correlation between fertility rate and infant mortality rate.

So…

Researchers have found that it is likely that a lowering of the infant mortality rate results in a lowering of the fertility rate. Their conclusions come from data spanning continents and centuries, and when you look at the issue through a human lens it makes sense: in general, if there’s a high chance children will die, people will have more children to mitigate the risk of losing all of their children. Hoarding might not make a lot of sense to those of us who live in countries with very low infant mortality, but it shouldn’t-I can only speak for myself, but my interests are more about quality of life rather than genetic survival. So, the fact that I only have one kid, is entirely predictable.

If the researchers are correct that lowering of the infant mortality rate lowers the fertility rate, then, by contributing to saving lives, we are also helping stem over-population. And even if the researchers are incorrect and the correlation is caused solely by something else, we can still be confident that giving to charities that take health measures, nutrition, women’s education and other important factors into account when saving lives, will have a non-zero impact.

Do you give to charity or volunteer? I’d love to hear some of your experiences.

Related material

- * This is from Population Dynamics of Humans and Other Animals by Ronald D. Lee. Malthusian dynamics is something I intend to cover in a future post.

- I encourage anyone interested in charity to visit Giving What We Can which calls on people to pledge 10% of their income to effective charities. It’s something I’ve done for 3 years now, and it’s not that painful, and makes a huge difference. My contribution works out to save 1 to 2 people’s lives every year-which feels pretty good.

- The purpose of using two studies is to show consensus rather than to cherry pick from one or the other-both studies come to generally the same conclusions.

- If you are interested in issues around charitable giving, you might want to check out the kindness equation

- The other factors that go into reducing over-population are really interesting, and I intend to focus an upcoming post on the role poverty plays.

- Contrasting with concerns about over-population, some prominent thinkers are currently concerned about a lack of population growth. I have yet to see any good reason for this concern-Matt Ball has an interesting post on this topic, which reflects my current view.

A great post, thanks for sharing this!

Thanks Siya

Executive summary: Contrary to the common belief that saving lives in overpopulated areas perpetuates overpopulation, evidence suggests that reducing infant mortality actually leads to lower fertility rates, creating a win-win situation where populations become more sustainable while lives are saved.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.