Yesterday, leading charity evaluator GiveWell announced they’re committing more money than ever to effective causes, which we commend. This generosity reflects great news: the world is wealthier than ever before. However, they also decided not to distribute $110M this year because they don’t believe they can find good enough ways to use it now. They will distribute $450M to programs they identified could spend funding over the next few years, but decided any additional donations were best saved for later. Their estimate is that they will roll over a similar amount of money next year. In the midst of a global pandemic that pushed 150 million people into extreme poverty while billionaires’ wealth grew by $5.5 trillion, it’s odd timing.

GiveWell’s rationale was fairly straightforward:

“We plan to roll over about $110M (~20% of our forecasted funds raised) into 2022 because we expect the opportunities this funding would be spent on now are much less cost-effective than those we expect to find over the next few years.” (GiveWell)

To be clear, we didn’t expect GiveWell to direct funds to GiveDirectly this year, and that’s not why we’re chiming in. While GiveWell has considered GiveDirectly a “Top Charity” for nearly a decade, they haven’t allocated funds to people in poverty through GiveDirectly since 2015. We’ve always appreciated GiveWell’s commitment to evidence and rigor, and many of us joined GiveDirectly after first hearing of it from GiveWell. We were motivated to respond precisely because we know first hand that GiveWell’s voice matters: they’ve established themselves as the gold standard charity recommender to answer questions for donors everywhere, like How To Make A Good Charitable Choice On Giving Tuesday.

As we share below, we think GiveWell is thinking too small, undervaluing what can be achieved today, underestimating the costs of waiting, overestimating how much better they’ll allocate funds in the future, and not accounting for the perspectives of people living in poverty. In short, we think the world has an unprecedented opportunity to eliminate most of extreme poverty in our lifetimes, and we worry GiveWell’s decision hinders that effort. Their choice to wait for better opportunities focuses on maximizing what they perceive as the direct impact of their money alone at the cost of conveying a tragically discouraging message about the potential impact of everyone else’s.

There is still immense need and opportunity for impact now

“In 2021, we expect to identify $400M in 8x [as cost-effective] or better opportunities. If our fundraising projections hold, we may have $160M (or more) that we’re unable to spend at our current bar… Given that, we expect to: Direct about $50M to 5-8x funding opportunities [and] Roll over about $110M to grant to future opportunities we expect will be 5x or better.” (GiveWell)

We think GiveWell is missing both the magnitude of extreme poverty and the abundance of the resources we have to fight it. Straining to find $500M or even $1B in worthwhile giving opportunities just doesn’t fit with a world where 700+ million people live in extreme poverty, U.S. charitable giving alone is nearly $500B a year, global official development assistance is another $150B a year, and an additional $500B has been pledged via The Giving Pledge. Even GiveWell’s largest few donors alone have enough wealth that it would take decades to distribute it at the pace GiveWell plans to achieve.

Once GiveWell’s top charitable opportunities are funded (like this year), what is everyone else to do? We’d say: keep giving as effectively as you can. The Life You Can Save recommends 16 organizations working on urgent matters of global health and wellbeing beyond those listed by GiveWell. Donors can cover the cost of treating obstetric fistulas or blindness, fight iodine deficiencies, or help low income farmers and entrepreneurs earn more. The Gavi Vaccine Alliance says there are 15M under-immunized children in countries where they already operate. And, of course, if you think people living in extreme poverty might know their needs best, there’s over 700 million of them who could each productively spend thousands of dollars if we gave it directly.

The team at GiveWell know all these numbers of course, and they would likely agree that influencing more money is better. But their decision here tries to optimize 0.1% of U.S. charitable giving in isolation from the other 99.9%; when, in reality, growing that 99.9% and allocating it better will mean a lot more for our world than asking those donors to hold out for possible silver bullets down the road.

Direct cash transfers can have much more impact than GiveWell assumes

“In the meantime, our best guess is that negative or positive spillover effects of GiveDirectly’s cash transfers program are minimal on net.” (GiveWell)

We know more about cash transfers than other interventions, so we’re able to be more specific about ways GiveWell may be underestimating the available cost-effectiveness of cash as an intervention with room to scale today. Also, all of GiveWell’s 5x or 8x cost effectiveness estimates are benchmarked to cash transfers delivered by GiveDirectly, so the tradeoffs of waiting for better opportunities are directly tied to the assessed cost-effectiveness of simply transferring wealth to people in extreme poverty. Cash transfers affect both the people who receive them and the people who live nearby. GiveWell assumes the latter effect is minimal, but a large-scale study evaluating our program in Kenya found each $1 transferred drove $2.60 in additional spending or income in the surrounding community, with non-recipients benefitting from the cash transfers nearly as much as recipients themselves. Since 2018, we have asked GiveWell to fully engage with this study and others, but they have opted not to, citing capacity constraints. Until they do, they may be underestimating the effects of cash transfers by 2.6x and overstating the benefits of waiting by the same amount.

We shouldn’t rely on finding sufficiently scalable, previously unconsidered interventions in the future

“We’re targeting $1 billion in annual funding opportunities identified by 2025. It’s ambitious, but we think it’s achievable.” (GiveWell)

GiveWell spent 14 years building a list of 5 interventions implemented by 8 charities they view as worth funding. Together, these interventions can put $490M to work over the next few years. GiveWell’s team is bigger now, but presumably they’ve also identified the “low hanging fruit” of sufficiently-effective opportunities, and these 8 charities have had years to prepare to scale. Even when an intervention is cost-effective, it’s not always sufficiently scalable, which is crucial when considering where to direct billions of dollars. We’re skeptical about GiveWell’s hopes to find much more without a more fundamental re-evaluation of the scale of the sector, the opportunities available, and their role within it. We hope we’re wrong about that, but if we’re not it’s another reason to move faster now, rather than hold out for better opportunities down the road.

People in extreme poverty should have more of a say about decisions like the one GiveWell made

“We think the cost of holding on to this $110 million is low compared to the reduction in impact we’d see from granting immediately.” (GiveWell)

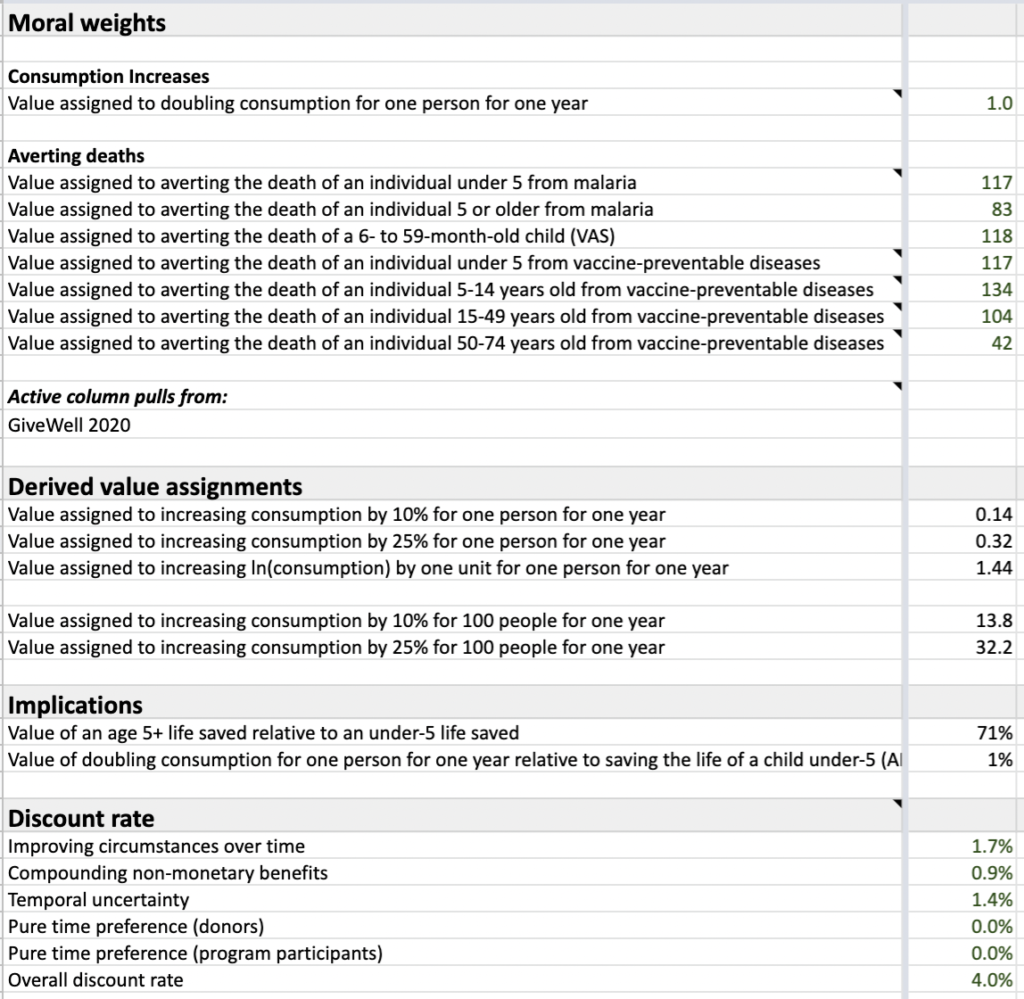

GiveWell’s decision today ultimately stems from their assumptions about the “moral weights” they assign to things like extending lifespan, doubling consumption, or achieving those effects sooner rather than later.

For example, this table from GiveWell’s website shows they’ve estimated that the value of averting the death of a child under 5 is 117 times greater than the value of doubling a person’s consumption for a year. Similarly, with a 4% discount rate, they’ve concluded that for people living in extreme poverty getting money a year later is only about 4% worse.

We commend GiveWell for their transparency, as many philanthropic decisions are opaque, made without stated reasoning. However, people living in poverty have good reasons to answer this table’s impossible questions in a variety of different ways. They may also have good reasons to differ with GiveWell on what else matters, let alone which interventions will do the most for the things that matter most to them. Many of these potential differences of opinion are highly relevant to whether or not GiveWell should save funds and give further down the road.

Nearly every decision about how to help people living in extreme poverty is made on their behalf by people living in relative wealth. We think that imbalance is grossly unjust. We also think it lowers the quality of the “help” people in poverty receive. The GiveWell team is incredibly intelligent, but they’re mainly Americans or Europeans who haven’t spent significant time in environments of extreme poverty. We applaud the work they did with IDinsight to understand better preferences of potential aid recipients, but the scale and scope of this survey doesn’t go nearly far enough in correcting the massive imbalances in power and lived experience that exist in their work and in philanthropy in general. Cash transfers are one way of acknowledging those gaps by letting the people we aim to help literally spend the budgets meant to help them. Absent that, we hope GiveWell does a lot more to incorporate the priorities of the people they exist to serve in life-and-death decisions like yesterday’s.

Fund all the opportunities identified by GiveWell, but don’t stop there

To be clear, GiveWell recommends excellent interventions. We want to live in a world where everyone who wants to can sleep under a mosquito net and where parents don’t have to worry about whether parasites or vitamin deficiencies will hold their kids back for decades to come. But we think there’s so much more we can accomplish. A universal basic income equal to the poverty line for each of the 700 million people living in extreme poverty would cost less than Americans give to charity every year. If that amount of money can go towards programs that do even more good than that, all the better. Just don’t leave those funds in the bank.

I think that this kind of criticism is really useful, and I am glad it was written.

That being said, there is something about this post that really rubbed me the wrong way. This is a shame, because the topic is very pertinent and deserves an in-depth discussion - how do opportunities for funding today compare to opportunities for funding 5 or 10 years from now?

Let me try to give my best shot at a more thoughtful critique.

This is pretty much an unrelated remark. While I agree that this reflects inequality and a sad arrangement of the world, it has very little to do with whether GiveWell should or not be patient.

I am pointing this out because this is one of things that made me icky about the post, even though it is a great post otherwise.

The argument here is that focusing on fundraising is probably a better use of GiveWell's resources than being patient with their money. But this assumes that fundraising trades off against patience, which I believe is false. GiveWell can focus on fundraising AND be patient.

I assume that the crux here is that GiveDirectly believes that spending more money now would have a good publicity effect, that would promote philanthropy and raise the total amount of donations overall.

I would change my mind if this was the case, but I don't see this as obvious.

This is the strongest argument in this document. If GiveWell has not taken into account these second hand effects and those would increase the effectiveness by x2 that might push them over the edge of effectiveness that would justify giving more now.

On the other hand, I am unsure of how much this affects the math on whether to expect better giving opportunities in the future. In fact, it could counterintuitively mean that good spending opportunities are easier to find than we expected, which could incentive waiting.

I agree with your position - if I believed that GiveWell has run out of low hanging fruit then this definitely is a good argument in favour of spending more now instead of waiting.

On the other hand, GiveWell is incredibly young. And they seem to be capacity constrained enough that they cannot afford to look into very relevant studies on cost-effectiveness like the one you mention in the post. I would be quite surprised if there weren't better funding opportunities than the ones already identified.

So it seems prudent to expect that better opportunities will be identified later.

I absolutely agree with this. And I commend GiveDirectly on its efforts to incorporate the voice of their recipients in their processes - I think its exemplary and something to be imitated.

I'd love to see GiveWell expand their work on this area, and to hire a more diverse team to help integrate many valuable perspectives.

I know very little about the chances of finding better funding opportunities in the future and of GiveWell and GiveDirectly. So please definitely take all of this with a grain of salt.

My TL;DR of the post is that GiveWell might be understimating direct giving and needs to do more work on listening to charity beneficiaries to learn how to help them best. It was also argued that GiveWell is unlikely to find better funding opportunities in the future, but I didn't find those arguments particularly convincing.

Thank you to GiveDirectly for taking the time to engage with the community. Highlighting these problems is definitely something I would like to happen more often, so we stand a better chance at fixing them.

"I assume that the crux here is that GiveDirectly believes that spending more money now would have a good publicity effect, that would promote philanthropy and raise the total amount of donations overall.

I would change my mind if this was the case, but I don't see this as obvious."

I'm not entirely sure what the answer is here either, but one thought I had today was "I should make a Facebook post for Thanksgiving/Christmas telling my friends why I think it's so important to donate to GiveWell - your marginal donation can save a life for $3-5k! Ah, but actually GiveWell won't disburse the marginal dollar I donate this year, so I can't really make that argument this year."

I do think from an optics perspective, when the draw from GiveWell is that your marginal dollar will actually help save someone's life, it's discouraging to see "you're marginal dollar will help save someone's life - in 3 years when we no longer need to roll over funds". It pushes me in the direction of "well I'll donate somewhere else this year and then donate to GiveWell in 3 years". And I know that's not the right calculation from a utility perspective - I should donate to the most cost-effective charity with little-to-no time discounting. But most people outside EA who might be attracted to effective giving have a yearly giving budget that they want to see deployed effectively in the near-term.

That's incorrect; GiveWell will in fact disburse the marginal dollar you donate this year. The only donation GiveWell doesn't expect to disburse this year is part of Open Philanthropy's donation.

I'm curious how you got the impression that GiveWell won't disburse donations other individuals donate to GiveWell this year? Was it from GiveWell's communications or from this GiveDirectly post or other content you've read (e.g. on the EA Forum)?

Very late response, thank you for catching this!

As GiveWell says in their post, "Because money is fungible, many gifts will effectively take the place of money that Open Philanthropy would have granted this year." If the result of me giving $1 is that the same amount of money goes to a top charity, and Open Phil gets to keep $1 extra, then Givewell hasn't disbursed the marginal dollar I've donated - they've rolled it over.

Disclosure I still did donate the same amount to GiveWell last year as I otherwise would have - this did just make me consider other options more than I had in previous year.

I think our disagreement may just be semantic, though I also have an intuition that something is problematic with your framing (thought it's also hard for me to put my finger on what exactly I don't like about it).

From the link in my previous comment, GiveWell writes: "Our expectation is that we’ll only be rolling over [part of] Open Philanthropy's donation, and we will direct other donor funds on the same schedule we have followed in the past."

I chose to accept GiveWell's framing of things (i.e. that your donation will not be rolled over), but your framing (in which your donation is rolled over) may be equally valid as long as you simultaneously claim that GiveWell will role over a smaller portion of Open Phil's donation than GiveWell claims it will rollover (smaller by the amount of your donation).

Then again, your framing has the issue that if every individual donor who was still considering donating made your claim that GiveWell would roll over their donation, then this would have been false since the sum of individual's donations was expected to be more than the amount that GiveWell intended to rollover. Maybe this wasn't actually an issue though given that it was highly unlikely that GiveWell's communications about rollovers would have caused individuals to donate $110M (the amount GiveWell expected to rollover) less than GiveWell originally forecasted they would.

I agree with most of your comment.

However, given that GiveWell want to use a bar of 5-7x GiveDirectly, I think accounting for a study that at best will demonstrate that GiveDirectly is 2.6 times more effective than previously thought, will not influence GiveWell’s decision to wait for better opportunities, since it still doesn’t meet the 5-7x GiveDirectly bar.

I agree that the criticism is very welcome and also in places felt a bit odd - I think your comment about the pandemic remark being both unrelated to GiveDirectly's arguments and very emotive captures why it doesn't feel quite right.

Some great points have been made in previous comments, but I think there is some important context missing in GiveDirectly's post and this discussion.

Disclosure and caveats: At Ayuda Efectiva we rely heavily on GiveWell's research and will soon incorporate GiveDirectly as a giving option for Spanish donors. We therefore have an ongoing relationship with GiveWell and a just-getting-started one with GiveDirectly. We talk to GiveWell regularly to get a better sense of their thinking but all I write here is my personal understanding (which could be wrong).

Even though GiveWell has been around for more than a decade, it is a fast-growing and fast-changing organization. It seems that one of the current key drivers of change is the success of their Maximum Impact Fund. More and more, donors seem to be choosing to let GiveWell pursue whichever opportunities they think are the most impactful at any given time.

The way I see it, what this means in practice is that GiveWell's role as a charity recommender is becoming less prominent while their role as a grantmaking organization is expanding. The 40% growth of their incubation grants in 2020 also seems to point in that direction.

Once you see GiveWell in that light, the arguments against the roll over of part of their 2021 let-GiveWell-decide money raised seem to me quite weaker. If there is a strong argument, it should be applicable to any foundation (e.g. Gates, Open Phil, you name it) not giving away all of their available money in cash transfers now.

I do find convincing the argument that GiveWell is still widely seen and represented as just a charity recommender and they do have an important influence on giving decisions (I would say mostly in the EA community and adjacent groups). Their communications can therefore have a big impact and potentially unintended consequences. I have two comments to make on this:

First, GiveWell's message to donors is not "do not give, hold your money":

In fact, they expect to cover funding needs in 2022 equivalent to a very large percentage of the money they hope to raise:

Second, I find GiveDirectly's argument on the potential impact of GiveWell's announcement rather confusing:

One possible interpretation is the one in Jaime's comment. The way I understood it made me think the argument is not very consistent: On the one hand, they say that GiveWell is trying to optimize 0.1% of U.S. charitable giving. I don't know what the exact percentage is but it does seem clear that GiveWell's money moved and influence is very small in the scheme of things. On the other hand, the post seems to suggest that GiveWell is somehow telling the 99.9% donors it has no influence on to hold their donations.

In any case, I think it is perfectly compatible for GiveWell to announce they will be holding some funds for some time in order to achieve maximum impact (since that is precisely what they set out to do) while other donors decide to give now because they prefer to address the immediate needs that GiveDirectly is focused on. It does not seem like GiveWell's announcement should have a huge impact on that latter group, even if it is not the messaging that GiveDirectly will want to (and should) emphasize when addressing the 99.9% donors out there.

I fully agree with your comment.

I want to agree with your points on delegating as much decision making directly to the affected populations, but my sense is that this is something GiveWell already thinks very seriously about, and has deeply considered.

For example, I personally felt very persuaded by some of Alex Berger's comments explaining that the advantage of buying bed-nets over direct transfers are that many of the beneficiaries are children, who wouldn't be eligible for GiveDirectly, and that ~50% of the benefits are from the positive externalities of killing mosquitoes, so people making individual choices would tend to underinvest.

I'm guessing you wouldn't find that argument compelling, or at least not sufficiently compelling, so I'd love to understand what I'm missing here, or why/how our views might differ.

This sounded pretty concerning to me, so I looked into it a bit more.

This GiveWell post mentions that they did engage with the study, or at least private draft results of it. An updated at the top of the post does clarify that they have not reviewed the full results. They explain the decision as:

I guess that decision sounds fine to me. They're basically saying that even taking the 2.6x multiple at face value, it doesn't put GiveDirectly ahead of any of their top charities, so it's not worth taking the time to fully evaluate it.

Does that seem unfair to you?

I'm not GiveDirectly, but in my view. It does make sense for GiveWell to deprioritise doing a more in-depth evaluation of GiveDirectly given resource constraints. However, when GiveWell repeatedly says in current research that certain interventions are or "5-8x cash", I think it would be helpful for them to make it more clear that it might be only "2-4x cash" - they just haven't had the time to re-evaluate the cash

I've written a post about why stepping up expenditure during a difficult time is often the correct thing to do here. I also talk about how I think the view of "let's wait and things will be easier in the future" is flawed.

TL;DR: GiveWell just announced ~$900M of giving recommendations this year, which they estimate are all at least 10 times as effective as cash transfers (10x cash). They only expect their donors to contribute $600M to these opportunities, leaving ~$300M unfunded. I think donors who have to GiveDirectly a year ago on GiveDirectly's recommendation would have done ~10x more good by giving to GiveWell instead (now, or earlier in the past year). I think this was very foreseeable and was disappointed by GiveDirectly's post here saying the opposite when I saw it last year.

Hi GiveDirectly,

I'm commenting on this post from a year ago because the results of GiveWell's research are finally in, so it's a good time for GiveDirectly to do a retrospective on this post.

(I'm also commenting because I was very disappointed by this post when I saw it last year—I felt it went against the principle of effective altruism that says you should try to do the most good, rather than settle for doing some good, and I want to speak my mind about that finally.)

GiveWell wrote the following in its newsletter that was sent out today, November 23, 2022 (bold emphasis added by me):

(See GiveWell's blog post for the full details: Our recommendations for giving in 2022.)

A year ago in this post, GiveDirectly wrote:

I strongly disagreed with this and GiveDirectly's condemnation of GiveWell's 2021 decision to rollover funds.

Let's look at the two concrete claims above that we now have new information on:

1.

GiveWell's funding bar was 5-8x cash last year, and decided to rollover funds that could not meet that funding bar to this year because GiveWell expected to identify significantly more giving opportunities above that bar. As it turns out, GiveWell did not overestimate how much better they'd allocate funds in the future. GiveWell's announcement today says:

As expected last year, any donors who gave to GiveDirectly last year rather than wait until today to give to GiveWell's 2022 recommendations lost out on ~90% of the impact they could have had with their money.

2.

estimate their top charities at 10x cash. So it seems they did not overestimate how much better they'll allocate funds.

I'm highly suspicious of GiveDirectly's claim that "[GiveWell may have been] underestimating the effects of cash transfers by 2.6x and overstating the benefits of waiting by the same amount," but for the sake of argument assume GiveDirectly is correct. Even cash transfers have always been 2.6x as valuable as GiveWell estimates, waiting a year to do 3-4 times as much good per dollar is still totally worth it.

GiveDirectly's claim that GiveWell was "underestimating the costs of waiting" still seems clearly false. Waiting a year to do 3-4 times as much good is a fantastic return.

But as a thought experiment, which is more likely?

Case A: A donor comes to GiveDirectly today and says, "I'm disappointed that the best giving opportunity I can identify today is GiveWell's recommendation which is 10x as effective as cash. I wish I could go back in time a year and give my money to GiveDirectly instead."

Case B: A donor comes to GiveDirectly today and says, "I donated to GiveDirectly last year because GiveDirectly recommended giving now after I heard about GiveWell's decisions to rollover funds, but I just learned that if I had waited just a year I could have done ~10 times as much good with my money."

Was happy to see you link to this. I agree the IDinsight surveys are simultaneously super useful and nowhere near enough.

My own sense is that more work in the vein of surveying people in extreme poverty to better calibrate moral weights would eventually alleviate something like 50% of my concern that donors are much wealthier than their recipients, but my interpretation of your phrasing makes me guess you would put that number at more like 5%.

What do you think would be a promising future scale and scope for surveys like this? Are those surveys being conducted? Do you worry that even much more comprehensive surveys wouldn't "go nearly far enough"?