What is effective altruism?

Effective altruism is a project that aims to find the best ways to help others, and put them into practice.

It’s both a research field, which aims to identify the world’s most pressing problems and the best solutions to them, and a practical community that aims to use those findings to do good.

This project matters because, while many attempts to do good fail, some are enormously effective. For instance, some charities help 100 or even 1,000 times as many people as others, when given the same amount of resources.

This means that by thinking carefully about the best ways to help, we can do far more to tackle the world’s biggest problems.

Effective altruism was formalized by scholars at Oxford University, but has now spread around the world, and is being applied by tens of thousands of people in more than 70 countries.1

People inspired by effective altruism have worked on projects that range from funding the distribution of 200 million malaria nets, to academic research on the future of AI, to campaigning for policies to prevent the next pandemic.

They’re not united by any particular solution to the world’s problems, but by a way of thinking. They try to find unusually good ways of helping, such that a given amount of effort goes an unusually long way. Here are some examples of what they've done so far, followed by the values that unite them:

What are some examples of effective altruism in practice?

PREVENTING THE NEXT PANDEMIC

Why this issue?

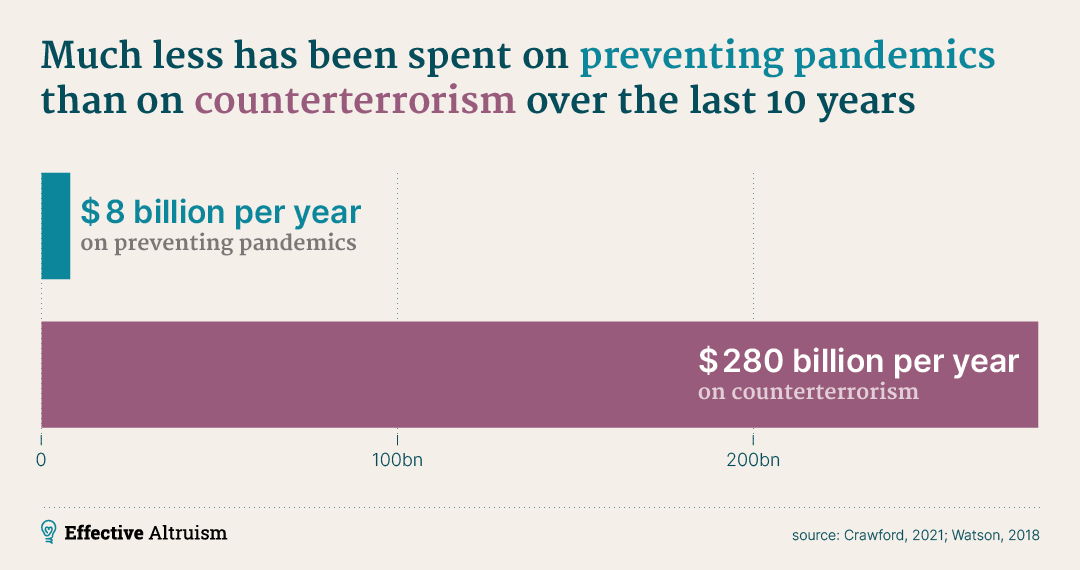

People in effective altruism typically try to identify issues that are big in scale, tractable, and unfairly neglected.2 The aim is to find the biggest gaps in current efforts, in order to find where an additional person can have the greatest impact. One issue that seems to match those criteria is preventing pandemics.

Researchers in effective altruism argued as early as 2014 that, given the history of near-misses, there was a good chance that a large pandemic would happen in our lifetimes

Another year, another World Malaria Day.

WHO reports that an estimated 263 million cases and 597 000 malaria deaths occurred worldwide in 2023, with 95% of the deaths occuring in Africa.

What’s still the case:

Malaria is still one of the top five causes of death for children under 5.

The Our World In Data page on Malaria is still a fantastic resource to learn about Malaria.

What’s different this year:

NB- this post is far from comprehensive. I'd appreciate people adding more information about the development of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes, or the speed of the malaria vaccine roll-outs in the comments.

Malaria vaccines.

We are now over a year into the launch of routine malaria vaccinations in Africa. GAVI has reported that 12 million doses of vaccines have been delivered to 17 countries. There are also very positive signs from the pilot, which ran from 2019-23 in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, as to the efficacy of the vaccine:

“Coordinated by WHO and funded by Gavi and partners, this pilot [run from 2019-23 in Kenya, Ghana and Malawi] reached over 2 million children, and demonstrated that the malaria vaccine led to a significant reduction in malaria illnesses, a 13% drop in overall child mortality and even higher reductions in hospitalizations.”

Read more on GAVI's website.

Cuts to foreign aid

In effective altruism spaces, we often hear about specific, highly effective charities, such as the Against Malaria Foundation and the Malaria Consortium.

But these charities can run such specific and effective programmes because of the larger ecosystem of which they are a part. This ecosystem runs on funding from WHO member states and philanthropists, and involves organisations such as GAVI and the Global Fund. The funding sources of these organisations are at risk due to the foreign aid pause in the US, and (to a lesser, but still significant extent) foreign aid cuts in the UK.

Additionally, services provided by the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) we

· · 3m read

We’re holding a DIY debate week on the Forum, from April 28 – May 4th.

What’s a DIY debate week?

It’s been great seeing and hearing people responding positively to debate weeks (1,2,3), writing posts, getting into discussions, and voting in large numbers.

I especially like that voting on the banner prompts people to leave a comment, which then starts discussions. I’d love to know if that vote→conversation pipeline holds if we let everyone make polls.

So… we are releasing a poll-making feature for everyone to use. We’re holding this DIY debate week to celebrate that release, during which we’ll ask users to make and discuss polls.

Throughout the week, the Forum team will promote polls we think are particularly valuable. This could be by pinning them on the Frontpage, linking them on social media, putting them in the Forum Digest, etc...

The polls will look like our debate week polls (a single axis with a label on each end, and a statement above), but unlike during debate week, they'll be in posts rather than on banners.

For a reminder - this is what a debate week poll looks like.

How can I take part?

Write a post with a poll in it. This could be a new genre for the Forum, so get creative. Some examples of uses of polls I’d love to see:

* Make the case for the importance of a particular discussion (this is what I do in debate week announcements), then put a poll under it.

* Make an argument, and for each proposition, make a separate poll (you can have as many polls in your post as you like).

* Write a dialogue with a friend, and use the poll feature to get the readers to vote on who they agree with the most.

How does the poll feature work?

It’ll look like the polls we’ve had for other debate weeks – it’ll be one axis, with a custom title, and custom labels on each end. You can use the poll to:

* Ask a yes or no question.

* Determine the reader’s preference between two outcomes.

* Ask for a level of agreement with a statement.

We expect the feature

· · · 38m read

In recent months, the CEOs of leading AI companies have grown increasingly confident about rapid progress:

* OpenAI's Sam Altman: Shifted from saying in November "the rate of progress continues" to declaring in January "we are now confident we know how to build AGI"

* Anthropic's Dario Amodei: Stated in January "I'm more confident than I've ever been that we're close to powerful capabilities... in the next 2-3 years"

* Google DeepMind's Demis Hassabis: Changed from "as soon as 10 years" in autumn to "probably three to five years away" by January.

What explains the shift? Is it just hype? Or could we really have Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)[1] by 2028?

In this article, I look at what's driven recent progress, estimate how far those drivers can continue, and explain why they're likely to continue for at least four more years.

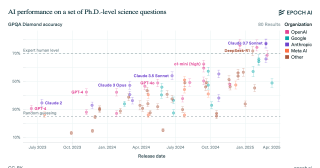

In particular, while in 2024 progress in LLM chatbots seemed to slow, a new approach started to work: teaching the models to reason using reinforcement learning.

In just a year, this let them surpass human PhDs at answering difficult scientific reasoning questions, and achieve expert-level performance on one-hour coding tasks.

We don't know how capable AGI will become, but extrapolating the recent rate of progress suggests that, by 2028, we could reach AI models with beyond-human reasoning abilities, expert-level knowledge in every domain, and that can autonomously complete multi-week projects, and progress would likely continue from there.

On this set of software engineering & computer use tasks, in 2020 AI was only able to do tasks that would typically take a human expert a couple of seconds. By 2024, that had risen to almost an hour. If the trend continues, by 2028 it'll reach several weeks.

No longer mere chatbots, these 'agent' models might soon satisfy many people's definitions of AGI — roughly, AI systems that match human performance at most knowledge work (see definition in footnote).

This means that, while the compa

· · 5m read

Below is the introduction to Giving What We Can's February 2025 newsletter, sent late February. Some information may now be out of date but we were encouraged to post this on the Forum as it contains practical information for thinking about donating!

EDIT 20th March: An non-final version of the newsletter was posted here in error. We are updating the "What's being done & how you can help" and "Supporting affected high-impact programs" sections to reflect the correct version.

It’s hard to believe the global health landscape has changed so significantly in just one month. We wanted to update our community on what we know so far and how this might impact your donation decisions.

(There is a lot to cover, so this newsletter will be a bit longer than usual!)

A summary of the situation:

The US aid funding freeze has left millions without access to critical global health services. While a judicial order was issued to temporarily reverse the freeze, the government is unlikely to comply. USAID staff & access to systems have been gutted, and – despite the government’s stated waiver program for life-saving work – many qualifying programs aren’t able to obtain waivers, and many who have them aren’t able to actually get the funding the waivers promise.

Many are wondering: “Is there anything I can do?”

What’s being done & how you can help

The good news is that several folks within the effective giving ecosystem are stepping up to help fill the funding gaps created by the chaos and help affected high-impact organisations continue their programmes. We’ll provide some information below about how you can support this crucial work. But first, here are a few things to keep in mind as you think about what this means for your donation decisions:

The situation is highly uncertain. It’s important to note that there’s a lot we don’t know and that it’s been difficult for organisations working on this to get clarity. It’s unclear if/how much funding will eventually resume and if

· · · 28m read

Note: I am not a malaria expert. This is my best-faith attempt at answering a question that was bothering me, but this field is a large and complex field, and I’ve almost certainly misunderstood something somewhere along the way.

Summary

While the world made incredible progress in reducing malaria cases from 2000 to 2015, the past 10 years have seen malaria cases stop declining and start rising. I investigated potential reasons behind this increase through reading the existing literature and looking at publicly available data, and I identified three key factors explaining the rise:

1. Population Growth: Africa's population has increased by approximately 75% since 2000. This alone explains most of the increase in absolute case numbers, while cases per capita have remained relatively flat since 2015.

2. Stagnant Funding: After rapid growth starting in 2000, funding for malaria prevention plateaued around 2010.

3. Insecticide Resistance: Mosquitoes have become increasingly resistant to the insecticides used in bednets over the past 20 years. This has made older models of bednets less effective, although they still have some effect. Newer models of bednets developed in response to insecticide resistance are more effective but still not widely deployed.

I very crudely estimate that without any of these factors, there would be 55% fewer malaria cases in the world than what we see today. I think all three of these factors are roughly equally important in explaining the difference.

Alternative explanations like removal of PFAS, climate change, or invasive mosquito species don't appear to be major contributors.

Overall this investigation made me more convinced that bednets are an effective global health intervention.

Introduction

In 2015, malaria rates were down, and EAs were celebrating. Giving What We Can posted this incredible gif showing the decrease in malaria cases across Africa since 2000:

Giving What We Can said that

> The reduction in malaria has be

Figure 1 (see full caption below)

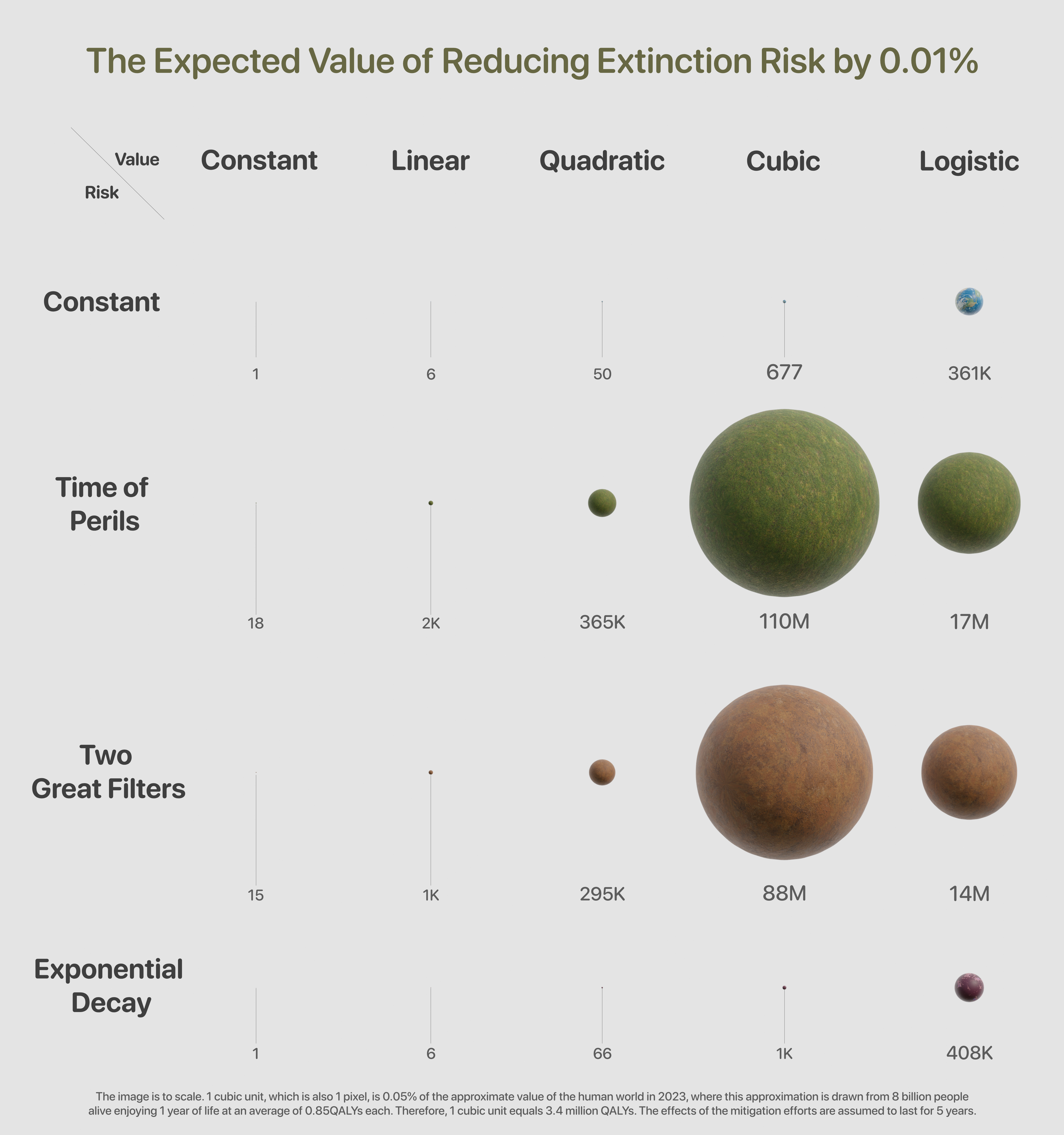

This post is a part of Rethink Priorities' Worldview Investigations Team's CURVE Sequence: "Causes and Uncertainty: Rethinking Value in Expectation." The aim of this sequence is twofold: first, to consider alternatives to expected value maximisation for cause prioritisation; second, to evaluate the claim that a commitment to expected value maximisation robustly supports the conclusion that we ought to prioritise existential risk mitigation over all else.

Executive Summary

Background

* This report builds on the model originally introduced by Toby Ord on how to estimate the value of existential risk mitigation.

* The previous framework has several limitations, including:

* The inability to model anything requiring shorter time units than centuries, like AI timelines.

* A very limited range of scenarios considered. In the previous model, risk and value growth can take different forms, and each combination represents one scenario

* No explicit treatment of persistence –– how long the mitigation efforts’ effects last for ––as a variable of interest.

* No easy way to visualise and compare the differences between different possible scenarios.

* No mathematical discussion of the convergence of the cumulative value of existential risk mitigation, as time goes to infinity, for all of the main scenarios.

* This report addresses the limitations above by enriching the base model and relaxing its key stylised assumptions.

What this report offers

1. There are many possible risk structure and value trajectory combinations. This report explicitly considers 20 scenarios.

2. The report examines several plausible scenarios that were absent from the existing literature on the model, like:

* decreasing risk (in particular exponentially decreasing) and Great Filters risk.

* cubic and logistic value growth; both of which are widely used in adjacent literatures, so the report makes progress in consolidating the model

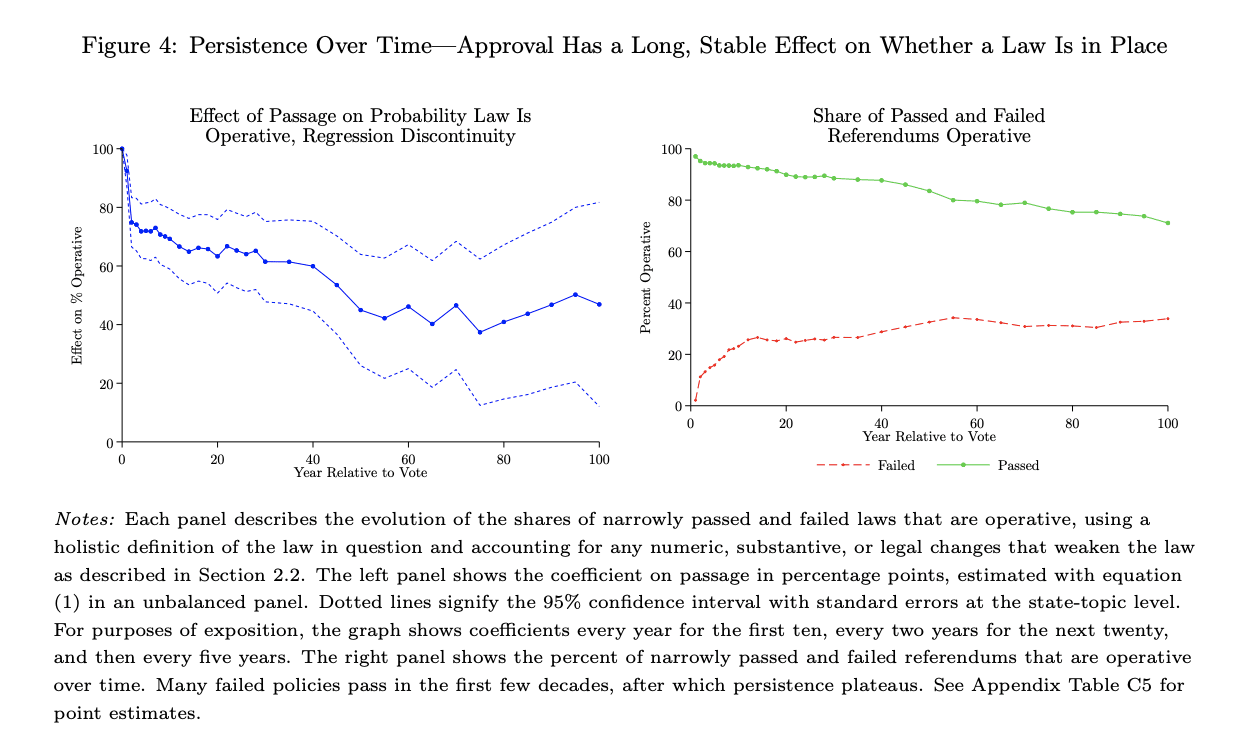

A key question for many interventions' impact is how long the intervention changes some output counterfactually, or how long the intervention washes out. This is often the case for work to change policy: the cost-effectiveness of efforts to pass animal welfare ballot initiatives, nuclear non-proliferation policy, climate policy, and voting reform, for example, will depend on (a) whether those policies get repealed and (b) whether they would pass anyway. Often there is an explicit assumption, e.g., that passing a policy is equivalent to speeding up when it would have gone into place anyway by X years.[1] [2] As people routinely note when making these assumptions, it is very unclear what assumption would be appropriate.

In a new paper (my economics "job market paper"), I address this question, focusing on U.S. referendums but with some data on other policymaking processes:

> Policy choices sometimes appear stubbornly persistent, even when they become politically unpopular or economically damaging. This paper offers the first systematic empirical evidence of how persistent policy choices are, defined as whether an electorate’s or legislature’s decisions affect whether a policy is in place decades later. I create a new dataset that tracks the historical record of more than 800 state policies that were the subjects of close referendums in U.S. states since 1900. In a regression discontinuity design, I estimate that passing a referendum increases the chance a policy is operative 20, 40, or even 100 years later by over 40 percentage points. I collect additional data on U.S. Congressional legislation and international referendums and use existing data on state legislation to document similar policy persistence for a range of institutional environments, cultures, and topics. I develop a theoretical model to distinguish between possible causes of persistence and present evidence that persistence arises because policies’ salience declines in the aftermath of referendums. The

· · 9m read

This is a Draft Amnesty Week draft. It may not be polished, up to my usual standards, fully thought through, or fully fact-checked.

Commenting and feedback guidelines:

This draft lacks the polish of a full post, but the content is almost there. The kind of constructive feedback you would normally put on a Forum post is very welcome.

Draft Amnesty Context: In the last year or two, I have noticed several ways in which the proxies that we use to communicate in effective animal advocacy can lose important nuance, leading to misunderstandings. I have even noticed a couple of times where these misunderstandings have found their way into important evaluative work, but not yet in a crucial/decision-relevant way. I intended to turn these observations into a stringent line of thought with a broader point, using real-world examples as citations and hard data to back up how they can be misleading. Now, waiting for an actual flaw to occur before posting something seems awfully pessimistic. I thus wanted to use Draft Amnesty Week as an opportunity to share these more anecdotal and only speculatively actionable observations—making further refinements feel less important. I also love and use proxies myself all the time, so I decided to add an “In defense of..” point to some of them. My observations are from the animal welfare space but may apply elsewhere as well. Thanks to @Johannes Pichler 🔸 and @Therese Veith🔸 for reviewing an even draftier version of this post. Thanks to @Toby Tremlett🔹 and the EA Forum team for hosting Draft Amnesty, it has done wonders in encouraging me. All mistakes are my own.

Nuances in Scale:

The following proxies all relate to the “scale of a problem” one might work on and how framing it on different levels can lose different nuances, each of which may lead to the impact of the work at hand being inaccurately assessed.

The Way We Group Animals

When prioritizing interventions, we sometimes categorize animals into broad groups, such as "farmed

TLDR: After artesunate rose from an obscure Chinese herb to be the lynchpin of malaria treatment, increasing resistance means we might need a fresh miracle.

Back in 2010 I visited Uganda for the first time, a wide eyed medical intern in the Idyllic Kisiizi rural hospital. In my last week malaria struck me down, but there was a problem – a nationwide shortage meant that no adult artesunate doses remained. Through an awkward mix of white privilege and Ugandan hospitality, I was handed the last four children’s doses to make up one adult dose. Even in my fever dream, I pondered the fate of those 4 kids who would miss out because of me…

Act 1 – The Origin

In the midst of the Vietnam war, a fierce arms race was afoot. But not for a killer – for a life saver. Troops died from more than just bullets, bombs and shrapnel – a nefarious killer roamed, and the drugs of the day weren’t good enough. “The incidence (of malaria) in some combat units..., approached 350 per 1,000 per year”. Chloroquine and quinine took too long to cure malaria and side effects were rough. Resistance to quinine was on the rise, “14 days proved inadequate to effect a radical cure, and there was a 70 to 90 percent rate of recrudescence within a month.” Soldiers might not die of malaria but could be out of action for weeks.

Both sides set their best scientists to the race. The Americans discovered that if you added an extra drug pyrimethamine, cure rates were higher and recovery was quicker -a useful development but hardly a game changer. The Chinese though had a secret weapon.

I’m proud that EAs lobby to normalise “challenge studies” as a quicker way to find cures than laborious multi-year RCTs. China's Tu Youyou was putting them to great use to help the North Vietnamese cause. Armed with malaria infected mosquitos and 2,000 traditional herbs, she wondered whether there was any merit in thousands of years of traditional Chinese medicine. After culling the initial list of 2000 to the 380 most pr

I wrote this to try to explain the key thing going on with AI right now to a broader audience. Feedback welcome.

Most people think of AI as a pattern-matching chatbot – good at writing emails, terrible at real thinking.

They've missed something huge.

In 2024, while many declared AI was reaching a plateau, it was actually entering a new paradigm: learning to reason using reinforcement learning.

This approach isn’t limited by data, so could deliver beyond-human capabilities in coding and scientific reasoning within two years.

Here's a simple introduction to how it works, and why it's the most important development that most people have missed.

The new paradigm: reinforcement learning

People sometimes say “chatGPT is just next token prediction on the internet”. But that’s never been quite true.

Raw next token prediction produces outputs that are regularly crazy.

GPT only became useful with the addition of what’s called “reinforcement learning from human feedback” (RLHF):

1. The model produces outputs

2. Humans rate those outputs for helpfulness

3. The model is adjusted in a way expected to get a higher rating

A model that’s under RLHF hasn’t been trained only to predict next tokens, it’s been trained to produce whatever output is most helpful to human raters.

Think of the initial large language model (LLM) as containing a foundation of knowledge and concepts. Reinforcement learning is what enables that structure to be turned to a specific end.

Now AI companies are using reinforcement learning in a powerful new way – training models to reason step-by-step:

1. Show the model a problem like a math puzzle.

2. Ask it to produce a chain of reasoning to solve the problem (“chain of thought”).[1]

3. If the answer is correct, adjust the model to be more like that (“reinforcement”).[2]

4. Repeat thousands of times.

Before 2023 this didn’t seem to work. If each step of reasoning is too unreliable, then the chains quickly go wrong. Without getting close to co

“No man is an island, entire of itself”. John Donne, Meditation XVII

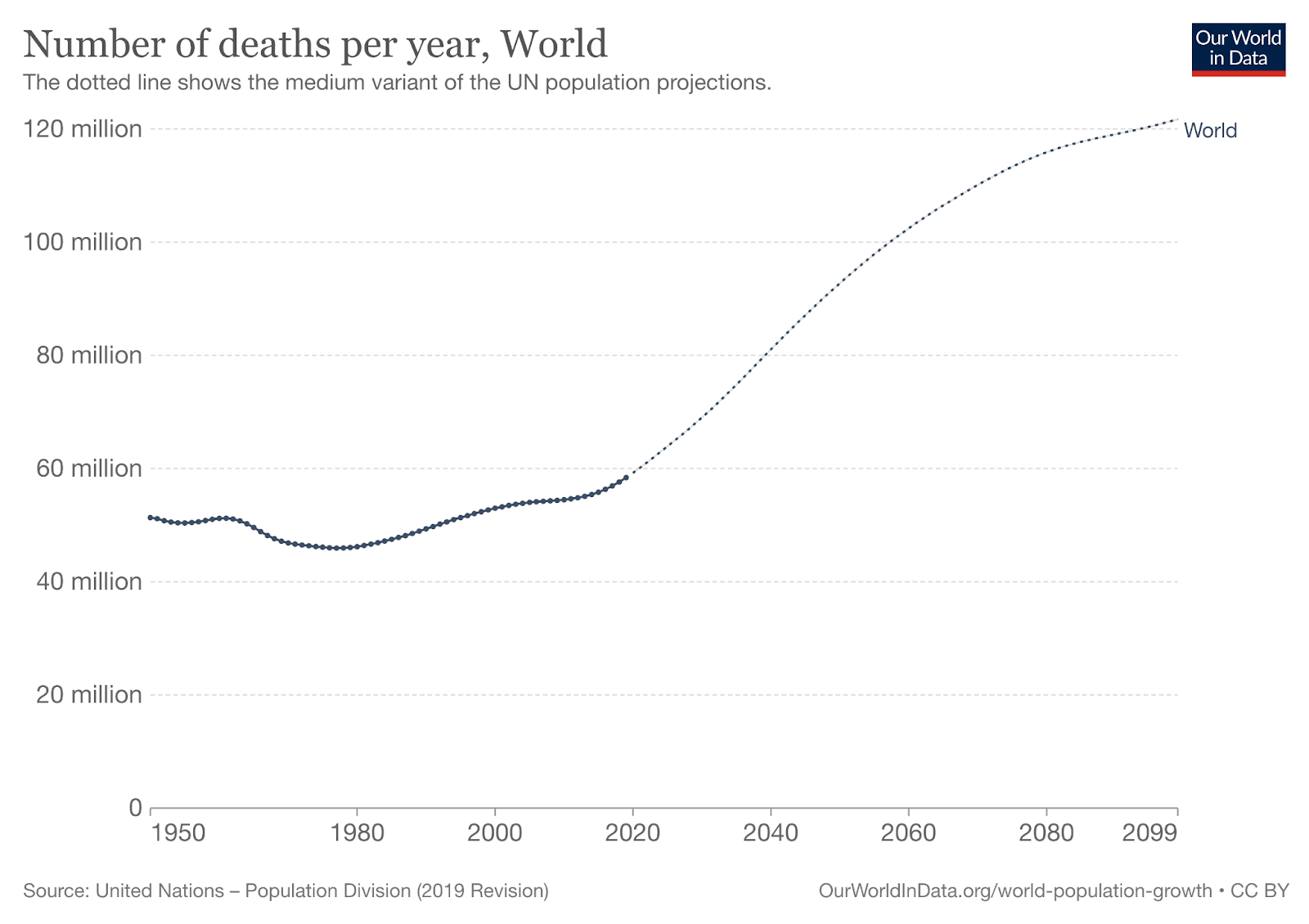

I want to know what’s going on in the world. I’m a human; I’m interested in what other humans are up to; I value them, care about their triumphs and mourn their deaths.

But:

* There’s far too much going on for me to keep track of all of it

* I think that some parts of what’s going are likely far more important than others

* I don’t think that regular news providers are picking the important bits to report on

I would really like there to be a scope sensitive news provider which was making a good faith attempt to report on the things which most matter in the world (see digression one for more thoughts on this). But as far as I know, this doesn’t exist (see digression two for some cool things which do exist).

In the absence of such a provider, I’ve spent a small amount of time trying to find out some basic context on what happens in the world on the average day. I think of this as a bit like a cheat sheet: some information to have in the back of my mind when reading whatever regular news stories are coming at me, to ground me in something that feels a bit closer to what’s actually going on.

Methodological notes

* I picked the scale of a day because it felt easiest to imagine. I think that weeks, months and years would all be interesting scales to have something like this for. (For decades and centuries, I mostly think you should just read most important century, and I strongly recommend doing so.)

* The numbers I’ve used are rough, but I think they are ballpark right, and a big improvement on no numbers.

* Please read all of the numbers as having a ‘~’ in front of them.

* I used the most recent years I could find, but this varied (2014-2022).

* I mostly pulled numbers from Our World In Data, and sometimes other places.

* I’ve only put links into the text directly where the number in the text is an annual figure that you can find directly in the original source. For everythin

· · 9m read

Crossposted from my blog which many people are saying you should check out!

Imagine that you came across an injured deer on the road. She was in immense pain, perhaps having been mauled by a bear or seriously injured in some other way. Two things are obvious:

1. If you could greatly help her at small cost, you should do so.

2. Her suffering is bad.

In such a case, it would be callous to say that the deer’s suffering doesn’t matter because it’s natural. Things can both be natural and bad—malaria certainly is. Crucially, I think in this case we’d see something deeply wrong with a person who thinks that it’s not their problem in any way, that helping the deer is of no value. Intuitively, we recognize that wild animals matter!

But if we recognize that wild animals matter, then we have a problem. Because the amount of suffering in nature is absolutely staggering. Richard Dawkins put it well:

> The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute that it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive, many others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear, others are slowly being devoured from within by rasping parasites, thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst, and disease. It must be so. If there ever is a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in the population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored.

In fact, this is a considerable underestimate. Brian Tomasik a while ago estimated the number of wild animals in existence. While there are about 10^10 humans, wild animals are far more numerous. There are around 10 times that many birds, between 10 and 100 times as many mammals, and up to 10,000 times as many both of reptiles and amphibians.

Beyond that lie the fish who are shockingly numerous! There are likely around a quadrillion fish—at least thousands, and potentially hundreds of thousands o

Here are four ideas that you probably already agree with. Three are about your values, and one is an observation about the world. Individually, they each might seem a bit trite or self-evident. But taken together, they have significant implications for how we think about doing good in the world.

Women in Uganda holding bales of insecticide-treated bednets provided by the Against Malaria Foundation, one of Giving What We Can's Top Charities.

The four ideas are as follows:

1. It's important to help others — when people are in need and we can help them, we think that we should. Sometimes we think it might even be morally required: most people think that millionaires should give something back. But it may surprise you to learn that those of us on or above the median wage in a rich country are typically part of the global 5%[1] — maybe we can also afford to give back too.

2. People[2] are equal — everyone has an equal claim to being happy, healthy, fulfilled and free, whatever their circumstances. All people matter, wherever they live, however rich they are, and whatever their ethnicity, age, gender, ability, religious views, etc.

3. Helping more is better than helping less — all else being equal, we should save more lives, help people live longer, and make more people happier. Imagine twenty sick people lining a hospital ward, who’ll die if you don’t give them medicine. You have enough medicine for everyone, and no reason to hold onto it for later: would anyone really choose to arbitrarily save only some of the people if it was just as easy to save all of them?

4. Our resources are limited — even millionaires have a finite amount of money they can spend. This is also true of our time — there are never enough hours in the day. Choosing to spend money or time on one option is an implicit choice not to spend it on other options (whether we think about these options or not).

I think that these four ideas are all pretty uncontroversial. I think it seems pretty intu

There’s something deeply wrong with the world, when the median US college graduate’s starting salary is a dozen times higher than the price to save another person’s entire life. The enduring presence of such low-hanging fruit reflects a basic societal failure to allocate resources in a way that reflects valuing those lives appropriately. (If you personally earn over $60k, and agree that your least-important $5k of personal spending is not nearly as important as a young child’s entire life, I’d encourage you to reallocate your budget accordingly and save someone’s life today. Then, if you’re happy with the results, consider taking the🔸10% Pledge to make it a regular thing. This should be the norm for anyone who is financially comfortable.)

It’s a tricky thing. If you really let yourself internalize this fact—that children are dying for want of $5000—it can be hard to think of anything else. How can life just go on as normal, when children are dying and we could easily prevent it? Why don’t more people treat this as the ongoing moral emergency that it is? Where is the urgency? Why aren’t most of the people around us doing anything?

Will you break through the barrier?

Psychological Defense 1: moral delusion

In order to live anything approximating a “normal life”, in these circumstances, we need to develop psychological defenses to block out the cacophony of global demands. And so we do. (Few are willing to be the sorts of radical altruists profiled in Strangers Drowning. I know I’m not!)

We learn to turn away, and ignore the needs of the world outside our local bubble. If people try to draw our attention back, we may even react with hostility: accusing them of being “preachy”, or “holier-than-thou”, or engaging in some kind of underhanded “guilt-tripping.” (How dare you break the social contract of mutually supporting each other’s delusions of decency, as we sip champagne while children starve?) We find—and elevate—other moral causes, preferably ones “closer to h

Cross-posted to Lesswrong

Introduction

Several developments over the past few months should cause you to re-evaluate what you are doing. These include:

1. Updates toward short timelines

2. The Trump presidency

3. The o1 (inference-time compute scaling) paradigm

4. Deepseek

5. Stargate/AI datacenter spending

6. Increased internal deployment

7. Absence of AI x-risk/safety considerations in mainstream AI discourse

Taken together, these are enough to render many existing AI governance strategies obsolete (and probably some technical safety strategies too). There's a good chance we're entering crunch time and that should absolutely affect your theory of change and what you plan to work on.

In this piece I try to give a quick summary of these developments and think through the broader implications these have for AI safety. At the end of the piece I give some quick initial thoughts on how these developments affect what safety-concerned folks should be prioritizing. These are early days and I expect many of my takes will shift, look forward to discussing in the comments!

Implications of recent developments

Updates toward short timelines

There’s general agreement that timelines are likely to be far shorter than most expected. Both Sam Altman and Dario Amodei have recently said they expect AGI within the next 3 years. Anecdotally, nearly everyone I know or have heard of who was expecting longer timelines has updated significantly toward short timelines (<5 years). E.g. Ajeya’s median estimate is that 99% of fully-remote jobs will be automatable in roughly 6-8 years, 5+ years earlier than her 2023 estimate. On a quick look, prediction markets seem to have shifted to short timelines (e.g. Metaculus[1] & Manifold appear to have roughly 2030 median timelines to AGI, though haven’t moved dramatically in recent months).

We’ve consistently seen performance on benchmarks far exceed what most predicted. Most recently, Epoch was surprised to see OpenAI’s o3 model achi

· · 5m read

Edit 1/29: Funding is back, baby!

Crossposted from my blog.

(This could end up being the most important thing I’ve ever written. Please like and restack it—if you have a big blog, please write about it).

A mother holds her sick baby to her chest. She knows he doesn’t have long to live. She hears him coughing—those body-wracking coughs—that expel mucus and phlegm, leaving him desperately gasping for air. He is just a few months old. And yet that’s how old he will be when he dies.

The aforementioned scene is likely to become increasingly common in the coming years. Fortunately, there is still hope.

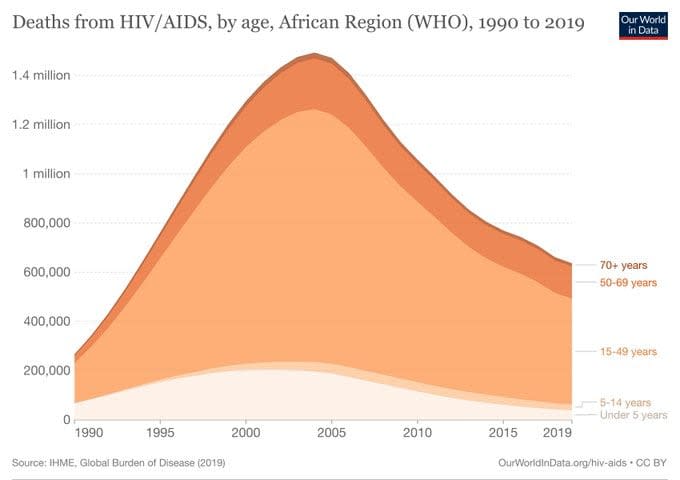

Trump recently signed an executive order shutting off almost all foreign aid. Most terrifyingly, this included shutting off the PEPFAR program—the single most successful foreign aid program in my lifetime. PEPFAR provides treatment and prevention of HIV and AIDS—it has saved about 25 million people since its implementation in 2001, despite only taking less than 0.1% of the federal budget. Every single day that it is operative, PEPFAR supports:

> * More than 222,000 people on treatment in the program collecting ARVs to stay healthy;

> * More than 224,000 HIV tests, newly diagnosing 4,374 people with HIV – 10% of whom are pregnant women attending antenatal clinic visits;

> * Services for 17,695 orphans and vulnerable children impacted by HIV;

> * 7,163 cervical cancer screenings, newly diagnosing 363 women with cervical cancer or pre-cancerous lesions, and treating 324 women with positive cervical cancer results;

> * Care and support for 3,618 women experiencing gender-based violence, including 779 women who experienced sexual violence.

The most important thing PEPFAR does is provide life-saving anti-retroviral treatments to millions of victims of HIV. More than 20 million people living with HIV globally depend on daily anti-retrovirals, including over half a million children. These children, facing a deadly illness in desperately poor countries, are now going

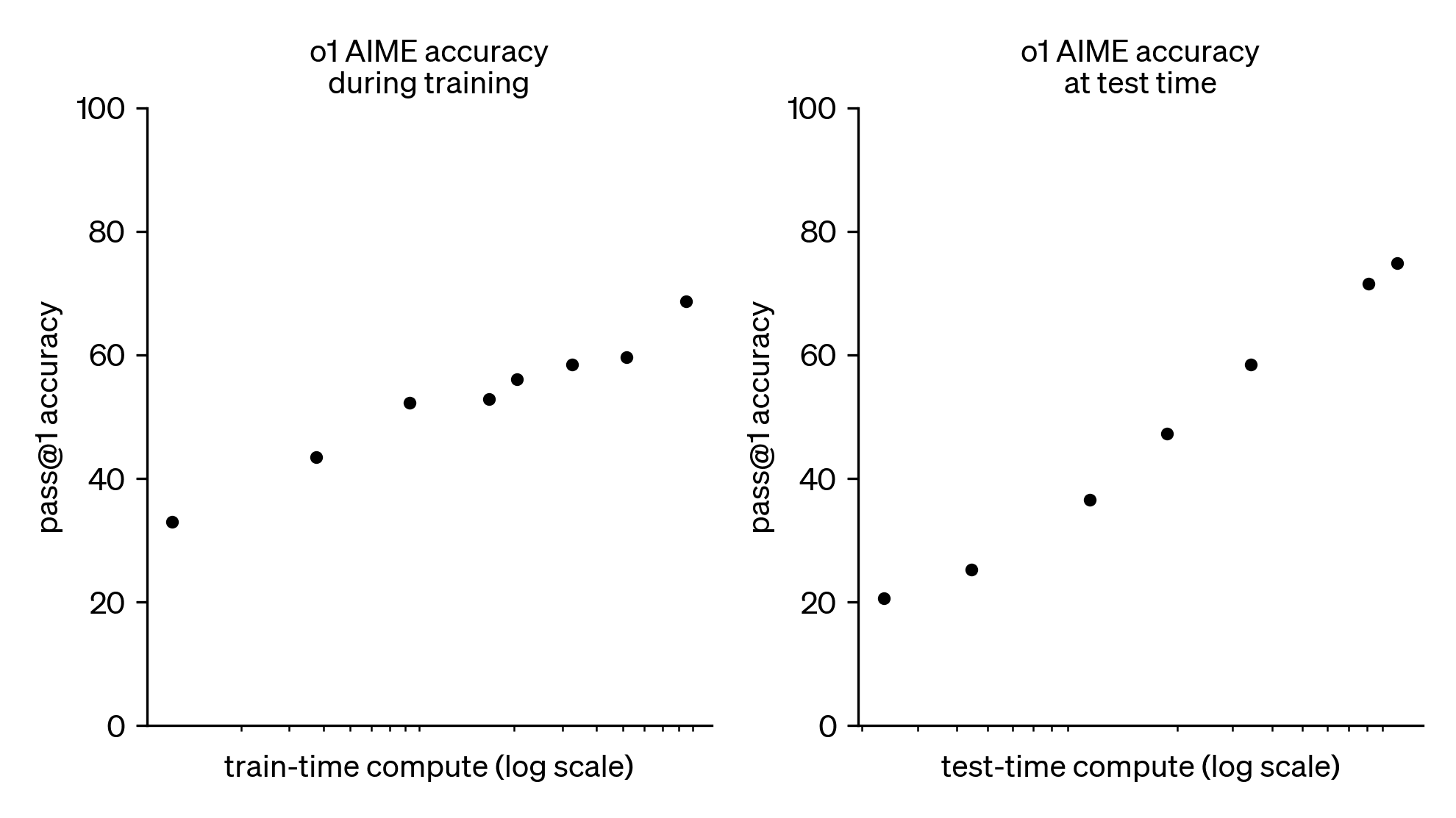

Scaling inference

With the release of OpenAI's o1 and o3 models, it seems likely that we are now contending with a new scaling paradigm: spending more compute on model inference at run-time reliably improves model performance. As shown below, o1's AIME accuracy increases at a constant rate with the logarithm of test-time compute (OpenAI, 2024).

OpenAI's o3 model continues this trend with record-breaking performance, scoring:

* 2727 on Codeforces, which makes it the 175th best competitive programmer on Earth;

* 25% on FrontierMath, where "each problem demands hours of work from expert mathematicians";

* 88% on GPQA, where 70% represents PhD-level science knowledge;

* 88% on ARC-AGI, where the average Mechanical Turk human worker scores 75% on hard visual reasoning problems.

According to OpenAI, the bulk of model performance improvement in the o-series of models comes from increasing the length of chain-of-thought (and possibly further techniques like "tree-of-thought") and improving the chain-of-thought (CoT) process with reinforcement learning. Running o3 at maximum performance is currently very expensive, with single ARC-AGI tasks costing ~$3k, but inference costs are falling by ~10x/year!

A recent analysis by Epoch AI indicated that frontier labs will probably spend similar resources on model training and inference.[1] Therefore, unless we are approaching hard limits on inference scaling, I would bet that frontier labs will continue to pour resources into optimizing model inference and costs will continue to fall. In general, I expect that the inference scaling paradigm is probably here to stay and will be a crucial consideration for AGI safety.

AI safety implications

So what are the implications of an inference scaling paradigm for AI safety? In brief I think:

* AGI timelines are largely unchanged, but might be a year closer.

* There will probably be less of a deployment overhang for frontier models, as they will cost ~1000x more to deploy than expec

> It seems to me that we have ended up in a strange equilibrium. With one hand, the Western developed nations are taking actions that have obvious deleterious effects on developing countries... With the other hand, we are trying (or at least purport to be trying) to help developing countries through foreign aid... Probably the strategy that we as the West could be doing, is to not take these actions that are causing harm. That is, we don't need to "fix" anything, but we could stop harming developing countries.

—Nathan Nunn, Rethinking Economic Development

EAs typically think about development policy through the lens of “interventions that we can implement in poor countries.” The economist Nathan Nunn argues for a different approach: advocating for pro-development policy in rich countries. Rather than just asking for more and better foreign aid from rich countries, this long-distance development policy[1] goes beyond normal aid-based development policy, and focuses on changing the trade, immigration and financial policies adopted by rich countries.

What would EA look like if we seriously pursued long-distance development policy as a complementary strategy to doing good?

The argument

Do less harm

Nunn points out that rich countries take many actions that harm poor countries. He identifies three main kinds of policies that harm poor countries:

1. International trade restrictions. Tariffs are systematically higher against developing countries, slowing down their industrialization and increasing poverty.

2. International migration restrictions. By restricting citizens of poor countries from travelling to and working in rich countries, rich countries deny large income-generation opportunities to those people, along with the pro-development effects of their remittances.

3. Foreign aid. This sounds counterintuitive—surely foreign aid is one of the helpful actions?–-but there's sizable evidence that foreign aid can fuel civil conflict, especially when given with

TL;DR:

In 2024, the farmed animal advocacy movement in Africa continued to grow, securing eleven local cage-free commitments across multiple countries. Five organizations spearheaded this progress: Animal Welfare League, Southern African Faith Communities' Environment Institute, Education for Africa Animals Welfare, Vegan and Animal Rights Society, and Utunzi Animal Welfare Organisation. This marked a significant increase from previous years, with Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya witnessing multiple commitments from local hotels, bakeries, and lodges to improve animal welfare standards for the first time.

Disclaimer: Thanks to Aurelia Adhiambo, OWA Africa Lead, for helpful input into this post. This post is a summary and commentary on cage-free wins in Africa in 2024. This post does not replace all the incredible work and impact groups in Africa achieved this year; read the organizations’ annual reports for more details. The information used in this post is available at chicken watch.

A decade ago, the farmed animal advocacy space in Africa was practically nonexistent, with most animal groups focusing on dogs, donkeys, and wild animal trafficking. However, the tide is changing for farmed animal welfare in Africa, as 2024 has seen more local cage-free wins than ever before.

Between 2016 and 2022, over fifteen organizations based in sub-Saharan Africa joined the Open Wing Alliance to address one of the most abusive practices in modern agriculture: cages. During this period, approximately seven combined cage-free commitments were secured, mostly from companies based in South Africa, according to public data on Chicken Watch. Animal Welfare League joined the Open Wing Alliance in 2022 and secured the only two cage-free commitments in Africa from hospitality companies outside of South Africa in 2023.

The progress in 2024 demonstrates significant momentum, with a total of eleven local cage-free commitments secured by five organizations: Animal Welfare League (AWL), South

· · 10m read

Does a food carbon tax increase animal deaths and/or the total time of suffering of cows, pigs, chickens, and fish? Theoretically, this is possible, as a carbon tax could lead consumers to substitute, for example, beef with chicken. However, this is not per se the case, as animal products are not perfect substitutes.

I'm presenting the results of my master's thesis in Environmental Economics, which I re-worked and published on SSRN as a pre-print. My thesis develops a model of animal product substitution after a carbon tax, slaughter tax, and a meat tax. When I calibrate[1] this model for the U.S., there is a decrease in animal deaths and duration of suffering following a carbon tax. This suggests that a carbon tax can reduce animal suffering.

Key points

* Some animal products are carbon-intensive, like beef, but causes relatively few animal deaths or total time of suffering because the animals are large. Other animal products, like chicken, causes relatively many animal deaths or total time of suffering because the animals are small, but cause relatively low greenhouse gas emissions.

* A carbon tax will make some animal products, like beef, much more expensive. As a result, people may buy more chicken. This would increase animal suffering, assuming that farm animals suffer. However, this is not per se the case. It is also possible that the direct negative effect of a carbon tax on chicken consumption is stronger than the indirect (positive) substitution effect from carbon-intensive products to chicken.

* I developed a non-linear market model to predict the consumption of different animal products after a tax, based on own-price and cross-price elasticities.

* When calibrated for the United States, this model predicts a decrease in the consumption of all animal products considered (beef, chicken, pork, and farmed fish). Therefore, the modelled carbon tax is actually good for animal welfare, assuming that animals live net-negative lives.

* A slaughter tax (a

TL;DR: The EA Opportunity Board is back up and running! Check it out here, and subscribe to the bi-weekly newsletter here. It’s now owned by the CEA Online Team.

EA Opportunities is a project aimed at helping people find part-time and volunteer opportunities to build skills or contribute to impactful work. Their core products are the Opportunity Board and the associated bi-weekly newsletter, plus related promos across social media and Slack automations.

It was started and run by students and young professionals for a long time, and has had multiple iterations over the years. The project has been on pause for most of 2024 and the student who was running it no longer has capacity, so the CEA Online Team is taking it over to ensure that it continues to operate.

I want to say a huge thank you to everyone who has run this project over the three years that it’s been operating, including Sabrina C, Emma W, @michel, @Jacob Graber, and Varun. From talking with some of them and reading through their docs, I can tell that it means a lot to them, and they have some grand visions for how the project could grow in the future. I’m happy that we are in a position to take on this project on short notice and keep it afloat, and I’m excited for either our team or someone else to push it further in the future.

Our plans

We plan to spend some time evaluating the project in early 2025. We have some evidence that it has helped people find impactful opportunities and stay motivated to do good, but we do not yet have a clear sense of the cost-effectiveness of running it[1].

We are optimistic enough about it that we will at least keep it running through the end of 2025, but we are not currently committing to owning it in the longer term.

The Online Team runs various other projects, such as this Forum, the EA Newsletter, and effectivealtruism.org. I think the likeliest outcome is for us to prioritize our current projects (which all reach a larger audience) over EA Opportunities, which

As 2024 draws to a close, I’m reflecting on the work and stories that inspired me this year: those from the effective altruism community, those I found out about through EA-related channels, and those otherwise related to EA.

I’ve appreciated the celebration of wins and successes over the past few years from @Shakeel Hashim's posts in 2022 and 2023. As @Lizka and @MaxDalton put very well in a post in 2022:

> We often have high standards in effective altruism. This seems absolutely right: our work matters, so we must constantly strive to do better.

>

> But we think that it's really important that the effective altruism community celebrate successes:

>

> * If we focus too much on failures, we incentivize others/ourselves to minimize the risk of failure, and we will probably be too risk averse.

> * We're humans: we're more motivated if we celebrate things that have gone well.

Rather than attempting to write a comprehensive review of this year's successes and wins related to EA, I want to share what has personally moved me this year—progress that gave me hope, individual stories and acts of altruism, and work that I found thought-provoking or valuable. I’ve structured the sections below as prompts to invite your own reflection on the year, as I’d love to hear your responses in the comments. We all have different relationships with EA ideas and the community surrounding them, and I find it valuable that we can bring different perspectives and responses to questions like these.

What progress in the world did you find exciting?

* The launch of the Lead Exposure Elimination Fund this year was exciting to see, and the launch of the Partnership for a Lead-Free Future. The fund jointly committed over $100 million to combat lead exposure, compared to the $15 million in private funding that went toward lead exposure reduction in 2023. It’s encouraging to see lead poisoning receiving attention and funding after being relatively neglected.

* The Open Wing Alliance repor