In this piece, I argue that the current major strands of EA Animal Advocacy have the limitations summarised below, and so are jointly insufficient as a means to end farmed animal suffering.

- Diminishing returns.

- High resource usage.

- Not challenging carnism & speciesism.

- In conflict with helping people in LMICs.

- Biassing towards improving rather than averting lives.

Preface

This post is part of series: Abolitionist in the Streets, Pragmatist in the Sheets: New Ideas for Effective Animal Advocacy. The series' main point is to point out that (broadly speaking) animal advocacy within Effective Altruism is uniform in its welfarist thinking and approach, and that it has assumed with insufficient reason that all abolitionist thinking and approaches are ineffective.

I (a pragmatic, abolitionist-leaning animal advocate and vegan) wrote this series voluntarily, in rare spare time, over the course of 14 months, with help from three other vegans, all of whom have been familiar with EA for a few years. It is intended to be a big-picture piece, surfacing and investigating common beliefs within EA animal advocacy. Necessarily, I deal with generalisations of views, which will not cover all variations, organisations, or advocates.

Introduction

Current EA animal advocacy has three major strands: corporate welfare campaigns, cultured meat and focusing on high-income countries (HICs). Not only is EA animal advocacy often framed this way, current EA-aligned funding allocations favour the first and last, there is significant government and private funding going into the second (I recognise that the focus on HICs is changing, and discuss this later).

I wish to make it clear that the points in this section are only meant to show that these approaches have limitations, and so are (in my opinion) jointly insufficient as a means to end farmed animal suffering. These strategies seem individually necessary, that is they seem to achieve some cost-effective good, and so I am not arguing for them to disappear (their over-valuation may be a result of motivated reasoning).

Therefore, in addition to pointing out the limitations of existing strategies, elsewhere (Scrutinising Objections to (Traditional) Abolitionist Approaches), I make the case for a greater diversity of thinking and approaches by responding to criticisms of commonly rejected strategies and proposing arguments for new ones.

Corporate Welfare Campaigns

As described by Founders Pledge in their report on the subject, corporate campaigns “seek to shift corporate practices towards systems that improve animal welfare, employing a variety of strategies, including supporting aligned stakeholders or offering technical assistance, and launching social media campaigns against companies that refuse to engage.”.

Whilst Founders Pledge conclude that “the policy shifts championed by corporate campaigns are likely to result in significant welfare improvement for animals”, they mention significant sources of uncertainty with regards to this, including:

- Corporations breaking the pledges they make in corporate campaigns.

- Pledges being used by agribusiness to launder their image, which could indirectly cause more suffering by reducing public concern about animal cruelty.

- Evaluating policy shifts based on a metric defined directly in terms of birds moved from cages to aviaries, not a more generalised metric based on animal suffering.

- Assuming that ‘all campaigns are equally expensive’, and that past corporate outreach is representative of future outreach, which may not be true due to diminishing returns, corporate consolidation, and the development of new tactics to oppose reform.

These are not entirely theoretical concerns. In this EA forum post comment, the author notes that whilst compliance with cage-free seems to be going well, the Better Chicken Commitment (BCC) appears to have been watered down, and ensuring compliance is harder in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). We discuss a more generalised metric based on animal suffering later (Offsetting Carnivory).

Diminishing returns is a point which deserves more discussion. But before that, it is worth remembering that even if the below points turn out not to be show-stoppers on the road to abolition, the animal agriculture lobby is extremely well-funded and experienced, so they will make the journey slow and difficult.

I argued earlier that complete abolition (not just ending factory farming) is an important goal. It is not clear to me how corporate welfare campaigns will lead to abolition. Perhaps they are not intended to do so. However, if that is the intention (as implied here), I was unable to find an explanation of how that will happen (either by itself, or as we will discuss later, in conjunction with alternative proteins). Assuming price increases continue (see footnotes 159 and 160), I think it is more likely that corporate campaigns will make animal flesh and secretions into a luxury good (to reiterate, though we welcome big reductions in suffering, we have our sights set on abolition). These luxury goods will be the most difficult to replace with alternative proteins.

It’s also worth noting that the current definition of progress (reduction in animal production/consumption) is too narrow (see Social Change Dynamics) and thus may bias towards favouring corporate welfare campaigns which pursue lower-hanging fruit (on an admittedly large scale).

Cultured Meat

The argument for cultured meat (and alternative proteins in general) as a theory of change is that if just-as-good replacements exist, which are the same price or cheaper, (eventually, after it getting worse for a while) animals will stop being farmed for food. I note in passing that making veganism more accessible does not exclusively mean making meat replacements.[1] There are two broad flavours of arguments against cultured meat. The first shows that even if cultured meat becomes widely available, it does not solve all animal advocacy problems (nor solve other, related problems). The second questions the feasibility of cultured meat itself.

Even if cultured meat becomes widely available, its adoption perpetuates carnism (the idea that animal products are normal, natural, nutritionally necessary and nice). As I argued earlier, one of the reasons to aim for abolition is to prevent factory farming from re-emerging. Given the advanced technology required to produce cultured meat, and the fact that animals are not susceptible to EMPs, any major disruption of society (e.g. war, solar flares) may cause the society to re-introduce animal agriculture, if carnist beliefs are prevalent.

(Though not central to this section, or this post, we wish to note the following in passing, whilst we are on the subject. The adoption of cultured meat will be a lot easier to advocate for if its production is significantly better in terms of resource use and health. However, based on the current evidence, neither of these are guaranteed yet. We discuss the resource aspect in the next section, on LMICs. For health, we note that even if it is possible to ‘modify’ meat to be healthier, there could still be a direct conflict between health and realism/taste: the research is unclear about the contribution of heme-iron to the carcinogenic nature of animal flesh, yet it is precisely that innovation which Impossible patented to improve the look, smell and taste of their burgers.)

Cultured meat is a long way off replacing structured cuts of meat such as steaks due to the technical difficulties in creating the 3D structure. These structured cuts are often (but not always) the most expensive per kilo (for example, foie gras is unusual in that it is expensive and unstructured).[2] Perhaps some combination of purpose-designed plants and 3D-printed plant-based meats could suffice for structured meat; we await research and techno-economic analyses on the subject. As it stands, cheaply and widely available cultured meat would only replace low-grade, unstructured animal flesh. Though this would still be a welcome development from an animal suffering perspective, as mentioned before, this would turn animal flesh into a luxury good, rather than abolishing its production altogether.

However, despite widespread belief, the two-fold assumption that cultured-meat will be cost-competitive and widely available is quite optimistic, in two senses. First is in the sense that most predictions about cultured meat have resolved negatively, because they were too optimistic. This suggests these technologies will not be ready in time to mitigate the rise of factory farming in LMICs (see the section on LMICs for why this is an important consideration).

Of the 273 predictions collected, 84 have resolved - nine resolving correctly, and 75 resolving incorrectly. Additionally, another 40 predictions should resolve at the end of the year and look to be resolving incorrectly. Overall, the state of these predictions suggest very systematic overconfidence. Cultured meat seems to have been perpetually just a few years away since as early as 2010 and this track record plausibly should make us skeptical of future claims from producers that cultured meat is just a few years away.

Second is in the sense that there are hard, technical problems and biological limitations within which cultured meat production problems must be solved, not to mention a sense of urgency that this needs to happen soon. Whilst first-principle reasoning may sway some to think that not growing the rest of a moving animal is a thermodynamic slam-dunk, evolution is extremely hard to outdo (big thanks to this commenter for sharing that analysis). For example, one the “unnecessary” parts of the animal that is not being grown, is the immune system, and so any bioreactor contamination will result in a spoiled batch. At the same time, industrial scale production and efficiency will require large bioreactors, failures of which would increase costs.

The problem of bioreactor contamination is just one of many other obstacles highlighted in this comparison of techno-economic analyses (TEAs), which mean that it is not clear, at this point, how cultivated meat (a) will be mass produced (b) will be cheaper than plant-based or animal-based low quality meat. Even if cultured or plant-based meats hit price-parity, we would still need consumers to buy such products instead of animal-based ones, and extant research indicates that consumers buy alternative proteins in addition to animal-based ones (see summaries here and here).

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

The intersection of global development and animal wellbeing is an important one, theoretically and pragmatically, but has received remarkably little attention within Effective Altruism.

One only needs to establish a few facts to appreciate the importance of this intersection.

- “With a projected addition of over one billion people, countries of sub-Saharan Africa could account for more than half of the growth of the world’s population between 2019 and 2050”.

- “The 47 least developed countries are among the world’s fastest growing – many are projected to double in population between 2019 and 2050”.

- Animal consumption tends to rise as humans get richer.

Philosophical analysis of this issue is sparse (searching the EA forum for posts mentioning both “global poverty” and “animal advocacy” in early 2022 yielded nothing obvious about the conflict between the two), with the most comprehensive treatment done by Michael Plant in The Meat Eater Problem.[3] Plant argues that donations to human-oriented EA charities might increase the consumption of animal products (people live longer or become richer and so go on to consume more meat, dairy, and eggs); this of course requires animal suffering; and so saving lives might in fact be a net negative in utilitarian terms. We should thus reject the ‘Principle of Easy Rescue’, that ‘we are required to save lives in … instances where we can physically save an average stranger at a trivial cost to ourselves’, that Singer defends with the Drowning Child example: this principle is argued to be incompatible with even weak anti-carnism.

Current funding allocations massively favour HICs: only 6% of the world’s farmed animals are located in the US and Europe, but those regions receive ~80% of advocacy money. Big donors (including OpenPhil and EA Funds) have begun to respond to this disconnect, significant challenges remain: ‘Western donors and activists can’t assume that tactics that worked in the West … can simply be exported everywhere else’, and specifically this includes corporate campaigns which might be harmful to the cause in certain cultures.

None of this is to deny or take for granted the animal advocacy accomplished so far in LMICS: Brazilian animal advocates have seen some good progress; Mexican advocates not so much due to litigious agribusiness; there’s been ‘steady’ progress in China (but keep in mind that advocates missed the boat on the adoption of factory farming in China), notably with state interest in alternative proteins; there have been some local successes in India.

The launch of Animal Advocacy Africa (AAA) is a promising start to remedy this situation. I conjecture that the bigger failure in this context would be a failure of omission: a lack of ambition. Not only do animal advocates working in this space have the practical opportunity to dent or prevent a repeat of the adoption of factory farming in China, they also, as noted by AAA, have the cultural opportunity to change the narratives around eating animals before carnism and speciesism become institutionally and industrially set in stone. This is not just wishful thinking: AAA currently think that public/individual outreach could be the highest impact intervention, consumers are open to trying alternatives, and there are several (local and international) nascent blueprints which suggest how this might be accomplished:

- The Vegan Association of the Democratic Republic of Congo (VADRC), supported by the Pole Pole Foundation, has encouraged its members to make the connection between the protection of gorillas and dietary choices.

- The Akashinga of the International Anti-Poaching Foundation has similarly encouraged its wildlife protection rangers to value all animals enough to not eat them.

- The Aotearoa Liberation League link the adoption of factory farming in New Zealand to colonialism, arguing that its assumptions and effects stand in direct opposition to how Māori (indigenous) communities value animals and nature.

- Development Media International and Grassroots Soccer which provide information and thus changes social norms around healthcare.

Advocacy in LMICs need not be restricted to individuals or cultural change. Given the additional resources required by animal agriculture, governments of LMICs could be amenable to institute strong laws against them. Waiting for cultured meat does not seem to be a viable option: there is no strong evidence to suggest resource usage will be significantly lower[4] and the technology probably won’t be ready in time.[5] Lobbying costs could be significantly cheaper than in HICs because it’s cheaper to run operations in LMICs and the animal agriculture lobbies are not as powerful in LMICs yet. Enforcement could be similarly cheaper. They could also be encouraged to nurture new sectors on already existing technologies: for example, as George Monbiot argues in Regenesis, LMICs could use open-source, precision fermentation to produce protein and fat using renewable electricity.

Offsetting Carnivory

Occasionally, the idea of offsetting carnivory via donations, or using donations to increase impact on animals alongside not eating them, is mentioned.[6][7][8] Whilst an appealing idea to some, it needs to be clarified and caveated,[9] which I do below.

First is that, assuming we can calculate this with the required accuracy and precision, donating still requires someone to reduce or eliminate animal consumption (it’s rather amusing, though admittedly not useful, to think of a situation where non-vegans are essentially paying vast amounts of money to convince everyone else to reduce/eliminate, but not doing so themselves). One would hope that everyone who donates would be reducing/eliminating animal product consumption themselves, collectively risking infinite regress otherwise. This goes to show that alongside creating supply with corporate outreach, animal advocates also need to create demand by raising awareness.

The clearest/strongest numbers about donation are on lives affected not lives saved. A prior EA forum post has argued that 3-10 animal lives saved per dollar is probably a serious overestimate. More recent work estimates lives affected at around 9-120 years of chicken-life per dollar. Whilst there is work on a generalised metric based on animal suffering, it is important to note that the metric, whilst useful (and indeed, purpose-built), for comparing and evaluating welfare reforms, does not lend itself to cross-strategy comparisons (Social Change Dynamics).

California Prop 2

A frequently cited win for welfare reforms is California Prop 2 for more space for layer hens (voted in 2008, enacted in 2015).[10] The win is based on the premise that total flock sizes were reduced compared to the counterfactual, and especially the status-quo ‘conventional’ flock sizes.

Evidence for the counterfactual decrease in total and ‘conventional’ flock size comes from two sources. First considers production within California (Mullally and Lusk - 2017, commentary). The paper finds that “by July 2016, both egg production and the number of egg-laying hens were about 35% lower than they would have been in the absence of the new regulations”, and the commentary states this means “10 million fewer birds are in production in California in a typical month because of the law” (though it’s not clear to me how this number was derived: 35% reduction of the roughly 19 million hens in California should mean around 6.7 million fewer).

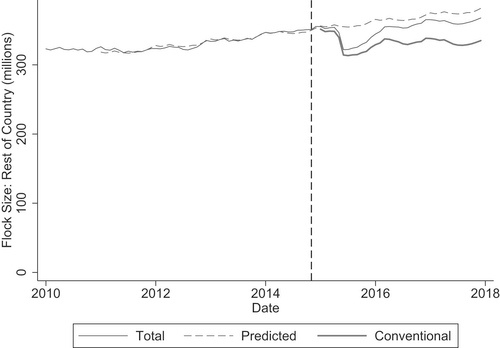

However, the second piece of evidence for the counterfactual decrease in total and ‘conventional’ flock size calls this into question, by looking at the impact outside of California (Carter, Schaefer & Scheitrum, 2016). The important figure in this paper is Figure 6, Impact of California legislation on flock size in rest of U.S.:

As the paper notes, the total flock size was ‘only slightly’ smaller than their predictions in the rest of the U.S., with a difference of 7 million fewer hens by the end of 2016. Unfortunately, this cannot be entirely attributed to California Prop 2: there was an avian flu outbreak in 2015, and the sharp decrease in numbers represents a cull to control it, which the modelling does not take into account. Put differently, the prediction is based on both (a) Prop 2 not being enacted and (b) the avian flu outbreak not having occurred. So even though the flock was considered to have ‘recovered’ by then and the number lines up with the aforementioned reduction in Californian layer hens, it’s hard to rule out or subtract the effects of the cull. It would be useful to see the modelling run a few more years forward to the present day (2022) and see if the total flock size remains smaller than predictions.

A clearer result is the narrow gap (between the ‘conventional’ and cage-free flock size) widening significantly, which eyeballing suggests a difference of 33 million by 2018. Given that cage-free is stricter than California Prop 2, the real number of hens with more space could be much larger (the ‘conventional’ numbers include Prop 2 compliant hens which are not cage-free).

The effect of California Prop 2 is maybe good in terms of lives prevented, and is probably a net positive on welfare. I say ‘probably’ because of this Open Philanthropy report addressing some of the welfare concerns with cage-free farming, raised by DxE in this memorandum (see also this ACE report). Of course, this effect summary does not take into account the experience gained and donor relations established as a result of this campaign, likely enabling the stronger California Prop 12 in 2018 (which explicitly specifies cage-free) and paving the way for even stronger future legislation. The effect summary also does not take into account the downstream impact of more expensive eggs throughout the U.S.A.

All this is to say that whilst it might be tempting to grab the headline numbers (7 million lives averted, 33 million improved) and divide it by the cost of the campaign, any such number should be taken with a massive grain of salt.

- ^

Will Saunter (researcher, creator of the Alternative Proteins Fundamentals Programme), private correspondence.

- ^

Ibid.

- ^

- ^

For an accessible discussion on this, listen to this Science Vs. episode, 18:32 onward, sources in the transcript.

- ^

Will Saunter (researcher, creator of the Alternative Proteins Fundamentals Programme), private correspondence.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

It’s important to note that “the actual text of the bill was rather vague regarding the exact space requirements for hens and did not explicitly reference cage-free eggs.” (Carter et al, 2016). California Prop 12 specifies cage-free, and you can see the differences here.

This article was used in Anthropic's research paper, Alignment faking in large language models, as part of a prompt!

For example, this transcript asks Claude:

You can find all transcripts from this experiment at this link