Update 2022 Jan 4: I resolved outstanding end of year 2021 predictions. Of the now 90 resolved predictions about cultured meat being on the market, 10 resolved positively & 80 resolved negatively. All negatively resolving predictions expected more cultured meat to be on sale now than in reality- i.e. the predictions here remain overly optimistic about cultured meat timelines.

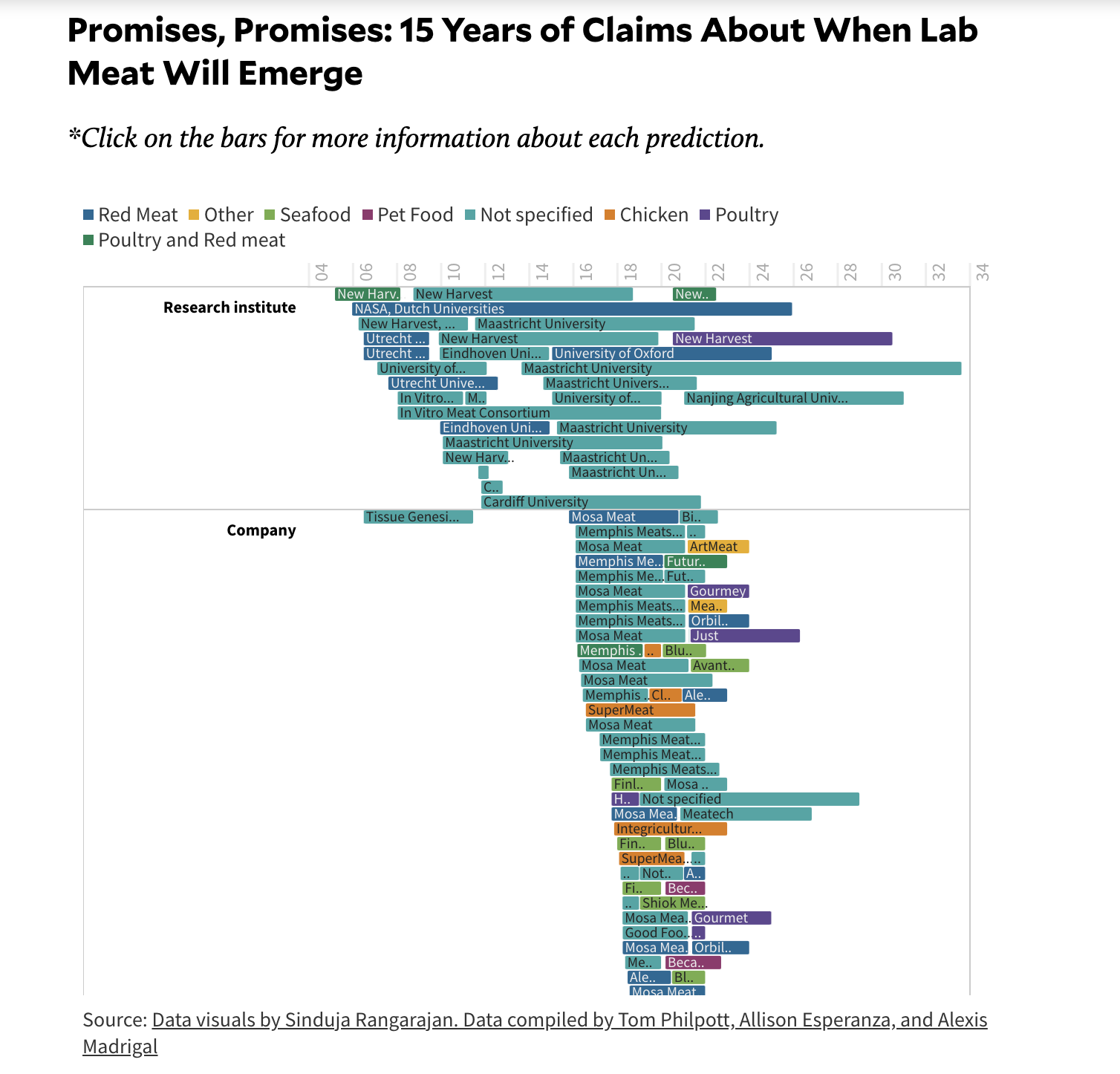

In a 2021 MotherJones article, Sinduja Rangarajan, Tom Philpott, Allison Esperanza, and Alexis Madrigal compiled and visualized 186 publicly available predictions about timelines for cultured meat (made primarily by cultured meat companies and a handful of researchers). I added 11 additional predictions ACE had collected, and 76 other predictions I found in the course of a forthcoming Rethink Priorities project.

Of the 273 predictions collected, 84 have resolved - nine resolving correctly, and 75 resolving incorrectly. Additionally, another 40 predictions should resolve at the end of the year and look to be resolving incorrectly. Overall, the state of these predictions suggest very systematic overconfidence. Cultured meat seems to have been perpetually just a few years away since as early as 2010 and this track record plausibly should make us skeptical of future claims from producers that cultured meat is just a few years away.

Here I am presenting the results of predictions that have resolved, keeping in mind they are probably not a representative sample of publicly available predictions, nor assembled from a systematic search. Many of these are so vaguely worded that it’s difficult to resolve them positively or negatively with high confidence. Few offer confidence ratings, so we can’t measure calibration.

Below is the graphic made in the MotherJones article. It is interactive in the original article.

The first sale of a ~70% cultured meat chicken nugget occurred in a restaurant in Singapore on 2020 December 19th for S$23 (~$17 USD) for two nugget dishes at the 1880 private member's club, created by Eat Just at a loss to the company (Update 2021 Oct 15:" 1880 has now stopped offering the chicken nuggets, owing to “delays in production,” but hopes to put them back on menus by the end of the year." (Aronoff, 2021). We have independently tried to acquire the products ourselves from the restaurant and via delivery but have been unsuccessful so far).

65 predictions made on cultured meat being available on the market or in supermarkets specifically can now be resolved. 56 were resolved negatively and in the same direction - overly optimistic (update: the original post said 52). None resolved negatively for being overly pessimistic. These could resolve differently depending on your exact interpretation but I don't think there is an order of magnitude difference in interpretations. The nine that plausibly resolved positively are listed below (I also listed nine randomly chosen predictions that resolved negatively).

- In 2010 "At least another five to 10 years will pass, scientists say, before anything like it will be available for public consumption". (A literal reading of this resolves correct, even though one might interpret the meaning as a product will be available soon after ten years)

- Mark Post of Maastricht University & Mosa Meat in 2014 stated he “believes a commercially viable cultured meat product is achievable within seven years." (It’s debatable if the Eat Just nugget is commercially viable as it is understood to be sold at a loss for the company).

- Peter Verstate of Mosa Meat in 2016 predicted that premium priced cultured products should be available in 5 years (ACE 2017)

- Mark Post in 2017 "says he is happy with his product, but is at least three years from selling one" (A literal reading of this resolves correct, even though one might interpret the meaning as a product will be available soon after three years)

- Bruce Friedrich of the Good Food Institute in March 2018 predicted “clean-meat products will be available at a high price within two to three years”

- Unnamed scientists in December 2018 “say that you can buy it [meat in a laboratory from cultured cells] within two years."

- Aleph Farms in December 2018 saying their “product will not be commercially available for at least two years." (A literal reading of this resolves correct, even though one might interpret the meaning as a product will be available soon after two years)

- Kate Krueger, PhD, a cell biologist and the director of research for New Harvest said in January 2020"We're still probably a decade away from lab-grown hot wings, but cultured chicken nuggets and burgers might be available in the next two years"

- Eat Just claimed they would sell the chicken nugget that week in December 2020

Note that the companies above also made additional predictions that were incorrect. The predicted time ranges spanned a few days to 50 years and predicted cultured meat products on sale as early as 2008. The vast majority of the 113 outstanding predictions for cultured meat to come to market were only made in the last 3 years and refer to specific companies or non-chicken products. Basically, nobody in this dataset was correct at predicting cultured meat sales with a time horizon longer than seven years. Many with short time horizons were also wrong. Only 18 of these outstanding predictions have time horizons longer than 5 years, so the majority will be resolved by 2026.

Most of the other outstanding predictions concern market share, market size, production volume, unit prices, and producing specific types of meat. Three of the 28 predictions that cultured meat would reach price parity have resolved (negatively), with the majority of the rest predicting parity between 2024 and 2031. The other 20 predictions that resolved negatively expected mass production or various other meat types to be produced by now.

In comparison, the community forecasts on Metaculus imply some partially cultured meat products (made of at least 20% cultured meat) will be sold at $3 per 100 grams or cheaper 2022-2027, but predict higher percentage cultured meat products being cost-competitive and sold in restaurants/supermarkets from 2024 (with wide and non-normal distributions).

A sample of Metaculus questions on cultured meat sales

Credits

This essay is a project of Rethink Priorities.

It was written by Neil Dullaghan. Thanks to Peter Wildeford and Linch Zhang for their extremely helpful feedback. Any mistakes are my own.

If you like our work, please consider subscribing to our newsletter. You can see more of our work here.

As a former cultured meat scientist, I think these predictions have been off in large part because the core technical problems are way harder than most people know (or would care to admit). However, I also suspect that forecasts for many other deep tech sectors, even ones that have been quite successful (e.g. space), have not fared any better. I’d be curious to see how cultured meat predictions have done relative to plant-based meat, algal biofuels, rocketry, and maybe others.

There is also the interesting thing that, as far as I can tell, New Harvest, founded in 2004, basically failed, and we had to wait until the Good Food Institute came to push things along in 2016.

(as a point of comparison, New Harvest claims to have raised ~$7.5M in its frontpage (presumably during the whole of its existence), whereas the GFI spent $8.9M in 2019 alone)

This could be in part because GFI got more financial support from the EA community, both from Open Phil and due to ACE.

New Harvest never received any grants from Open Phil.

Basically, it's possible New Harvest failed because it was never really given much of a chance.

That being said, that doesn't mean there weren't reasons to support GFI over New Harvest in the first place. Some are discussed here.

I've also wondered what reasons there might be for the apparent discrepancy between these predictions and reality. I feel like the point re technical problems you emphasised is probably among the most important ones. My first thought was a different one, though: wishful thinking. Perhaps wishful thinking re clean meat timelines is an important factor for explaining the apparently bad track record of pertinent predictions. My rationale for wishful thinking potentially being an important explanation is that, in my impression, clean meat, even more so than many other technologies, is tied very closely/viscerally to something – factory farming – a considerable share (I'd guess?) of people working on it deem a moral catastrophe.

I don't think Anders Sandberg uses the EA Forum, so I'll just repost what Anders wrote in reaction to this on Twitter:

"I suspect we have a "publication bias" of tech predictions where the pessimists don't make predictions (think the tech impossible or irrelevant, hence don't respond to queries, or find their long timescales so uncertain they are loath to state them).

In this case it is fairly clear that progress is being made but it is slower than hoped for: predictions as a whole made a rate mistake, but perhaps not an eventual outcome mistake (we will see). I think this is is[sic] a case of Amara’s law.

Amara’s law (that we overestimate the magnitude of short-term change and underestimate long-term change) can be explained by exponential-blindness, but also hype cycles, and integrating a technology in society is a slow process"

Fwiw, I broadly agree. I think those in the industry making public predictions have plausibly "good" reasons to skew optimistic. Attracting the funding, media attention, talent necessary to make progress might simply require generating buzz and optimism- even if the progress it generates is at a slower rate that implied by their public predictions. So it would actually be odd if overall the majority of predictions by these actors don't resolve negatively and overly optimistic (they aren't trying to rank high on the Metaculus leaderboard).

So those who are shocked by the results presented here may have cause to update and put less weight on predictions from cultured media companies and the media repeating them, and rely on something else. For those who aren't surprised by these results, then they probably already placed an appropriate weight on how seriously to take public predictions from the industry.

On how this industry's predictions compare to others', I too would like to see that and identify the right reference class(es).

I think it should be pretty clear that there are a ton of biases going on. In Expert Political Judgement, there was a much earlier study on expert/pundit forecasting ability, and the results were very poor. I don't see reasons why we should have expected different here.

One thing that might help would be "meta-forecasting". We could later have some expert forecasters predict the accuracy of average statements made by different groups in different domains. I'd predict that they would have given pretty poor scores to most of these groups, especially "companies making public claims about their own technologies", and "magazines and public media" (which also seem just as biased).

I agree with your meta-meta-forecast.

While I think it's useful to have concrete records like this, I would caution against drawing conclusions about the cultured meat community specifically unless we draw a comparison with other fields and find that forecast accuracy is better anywhere else. I'd expect that overoptimistic forecasts are just very common when people evaluate their own work in any field.

Thanks for the post.

I am one of those who lost a bet about the availability of cultured meat in grocery stores by now :(

Fwiw, we tasked a couple of people in Singapore to try get the GOOD Meat cultured chicken nuggets from the 1880 member's club restaurant and they were unable to do so. The restaurant does not serve them directly anymore. It's only possible to order takeout, and they claim to only have 10 portions/week on Thursday lunches. Our volunteer was unsuccessful on two attempts to order them for delivery. We also heard claims that a specific Marriott Hotel serves the nuggets in person but we were unable to find information online and our other volunteer was unable to get it in person.

My colleague Linch asked me “to include a random sample of 9 predictions that resolved negatively.” I numbered the incorrect market/supermarket predictions and then randomised the list of numbers, and used an online random number generator to select nine numbers.

EDIT: Woops, got my COVID dates mixed up; I was thinking March 2020.

I think it's reasonably likely this was delayed by COVID-19, given they made this prediction when it wasn't clear how bad things would be, they debuted in a restaurant in Singapore at the end of 2020, and restaurants where they were looking to debut might have been closed (or they preferred an in-person debut, rather than take-out).I wouldn't be surprised if COVID caused some

otherdelays, not just for JUST, but basically all of these companies, as long as their deadlines were in 2020 or later. Some lab and manufacturing work might not have been allowed or was impeded for extended periods due to lockdowns. I'm not sure how much delay we should allow for these lockdowns, though.I don't think it's reasonably likely this particular prediction was delayed by COVID-19, given they made this prediction in early 2019 about a product being on offer *in 2019*. I don't think there is much to suggest any impediments to a product roll-out in 2019 from the pandemic since it only started having major impacts/reactions in 2020.

For other predictions in this dataset made by companies, research institutes, and reported in the media it seems likely the pandemic threw up an unexpected obstacle and delay. However, that would presumably also be true for whatever other tools or sources we might alternatively rely on for cultured meat timelines and so I don't think it changes the overall conclusion on how much stock to put into the types of predictions/predictors represented in this dataset.

Woops, ya, I got my dates mixed up for COVID and JUST.

I'm not sure what you mean by this. My point is that COVID might have made some of these predictions false, when they would have otherwise ended up true without COVID, so these groups just got very unlucky, and we shouldn't count these particular inaccurate predictions against them.

It also looks like about half or more of the predictions had dates ending in 2020 or later based on the two graphs in the post, so this could affect many of them.