One of the most prominent people in global health died last month.

Wikipedia makes it hard to see what Paul Farmer actually did, behind the mountain of honors and appointments he received for it (Harvard prof, MacArthur grant, UN envoy, etc). He cofounded Partners In Health, now a $100m+ per year organisation. PIH works in Haiti, Peru, Mexico, Russia, Lesotho, Kazakhstan, Rwanda, Malawi, Sierra Leone, India and Liberia, greatly upgrading the quality of healthcare near their operations, and doing a huge amount of welfare programmes besides.

They class themselves as a humanitarian organisation, though most of their work is not the crisis work you'd associate with that (except incidentally, as when an earthquake happened next to the hospital they were building).

They do a huge, huge variety of things, under the root-cause theory of public health, where stuff like good shelter and food is treated as part of healthcare. They started out doing HIV treatment - and once you're doing that it only makes sense to do HIV prevention - and after that you're kinda hosed. An incomplete list: "HIV treatment, tuberculosis treatment... food baskets, transportation, lodging... dirty water... from in-home consultations to cancer treatments... job skills training, small business loans... a university in Rwanda... the world's largest TB research study... biocontainment unit in Lima... allowing [children] to attend school and receive food".

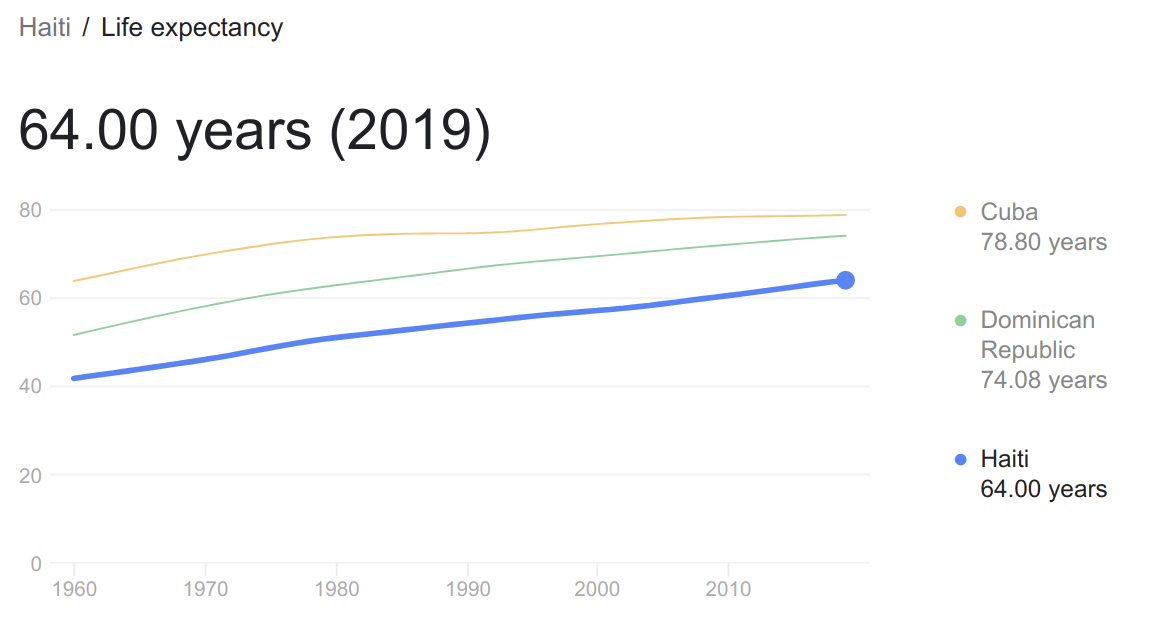

Farmer's most notable work is being the single most powerful advocate for Haitian public health; PIH staff serve nearly half the entire country, and he was mates with Bills Clinton and Gates. Haiti will need another Farmer:

He was an anthropologist by trade. In the past I've gotten annoyed with anthropology for bad epistemics (or for conflating good epistemics and good activism). But it's hard to fault Farmer as exemplar of the general approach "don't just watch, do something".

I take his lifework to amount to the importance of operations. He didn't develop any vaccines or pills, he didn't make a pile of cash and give it away, and his research wasn't the main feature. Instead (as per Wikipedia) his org "created specific initiatives", "improved medical infrastructure" and provided "accompaniment rather than charity". (As with all large development organisations, they have their own homebrew intellectual framework, "Supervision-Partners-Incentives-Choice-Education".) Suitably unglamorous terms for good unglamorous things.

He was extremely good at getting powerful people to care. There's a whole book about him, and he has been widely elegised. This marks out his strategy as the prestige route, using the system. Near the ceiling of that approach, perhaps.

Achievements

As usual in global health, most discussion of PIH's impact is actually about their inputs: number of staff, number of programmes, etc. (Not their budget though, which is both good and bad.)

GiveWell gave them an ultra-tentative recommendation in 2007, but this was largely on priors about good healthcare in countries with a shortage of it. ("We would guess that it is improving health outcomes") When evaluated properly in 2010, GW found that PIH weren't formally evaluating their own work and mostly wouldn't share their programme budgets, and so they couldn't give them the internalist stamp of approval. ("We would guess that they are outside – though not necessarily far outside – what we consider to be a reasonable range [of cost-effectiveness].")

- "focused on AIDS prevention during the HIV crisis and successfully decreased HIV transmission rates by 4% from mothers to babies"

- Built and run several hospitals, including 40% of Haiti's medical system. One nice feature: they're big on videoconferencing for American docs to train Haitian staff remotely.

- fighting tuberculosis outbreaks across the world

- I don't know how important his own research is. It didn't come up in my brief stint in international development.

The sheer variety of non-health programmes I mentioned above is usually a bad sign, but at least in Rwanda in 2010 about 93% of their spending was on health programmes.

As with most global health work, and even most good global health work, we can't easily say how much good they've done. It should be possible for someone to reconstruct the total impact of PIH given lots of time and effort. For now I'll just note that it's hundreds of millions of improved doctor visits and probably millions of QALYs lifted.

Cost

Epistemic status: Literally guesswork with two weak constraints.

>$100m a year now. But PIH were <$10m for the first 14 years. A crappy guess of their total lifetime spend is then $750m.

Colour

- He apparently subscribed to "liberation theology" (roughly: Catholic socialism). This is perhaps one of the larger anti-poverty movements in the world, but it has zero mentions on the forum, since it is triply distant from us: religious, Latin American, and politically activist.

- Another dedicated global health worker turned down his marriage proposal because he was too extra:

For a long time I thought I could live and work in Haiti, carving out a life with you, but now I understand that I can’t. And that’s simply not compatible with your life... the qualities I love in you — that drew me to you — also cause me to resent you: namely your unswerving commitment to the poor, your limitless schedule and your massive compassion for others. You were right, and, as your wife, I would place my own emotional needs in the way of your important vision; a vision whose impact upon the poor (and the rest of us) can’t be exaggerated

- His biographer:

I was drawn to the man himself. He worked extraordinary hours. In fact, I don’t think he sleeps more than an hour or two most nights. Here was a person who seemed to be practicing more than he preached, who seemed to be living, as nearly as any human being can, without hypocrisy. A challenging person, the kind of person whose example can irritate you by making you feel you’ve never done anything as important, and yet, in his presence, those kinds of feelings tended to vanish. In the past, when I’d imagined a person with credentials like his, I’d imagined someone dour and self-righteous, but he was very friendly and irreverent, and quite funny. He seemed like someone I’d like to know...

Thanks for writing this, Gavin.

Reading (well, listening to) Mountains Beyond Mountains, I was deeply inspired by Farmer. I think a lot of people in the EA community would benefit from giving the book a chance.

Sure, I sometimes found his rejection of an explicit cost-effectiveness-based approach very frustrating, and it seemed (and still seems) that his strategy was at times poorly aligned with the goal of saving as many lives as possible. But it also taught me the importance of sometimes putting your foot in the ground and insisting that none of the options on the table are acceptable; that we have to find an alternative if none of the present solutions meet a certain standard.

In economics and analytic philosophy (and by extension, in EA) we're often given two choices and told to choose one, regardless of how unpalatable both may be. Maximisation subject to given constraints, it goes. Do an expensive airlift from Haiti to Boston to save the child or invest in cost-effective preventive interventions, it goes. And in the short term, the best way to save the most lives may indeed be to accept that that is the choice we have, to buckle down and calculate. But I'd argue that, sometimes, outright rejecting certain unpalatable dilemmas, and instead insisting on finding another, more ambitious way, can be part of an effective activist strategy for improving the world, especially in the longer term.

My impression is that this kind of activist strategy has been behind lots of vital social progress that the cost-effectiveness-oriented, incrementalist approach wouldn't be suited for.

Insisting that we have to find an alternative seems justified only insofar as there are reasons for expecting alternatives to exist. I agree that, because some causes or interventions are hard to quantify, these reasons may be provided by things other than explicit cost-effectiveness analyses. But the fact that a certain standard hasn't been met doesn't seem, in itself, like one of these reasons.

Separately, one also needs to consider the costs of having a social norm that allows and even encourages people to "reject[t] certain unpalatable dilemmas", without requiring them to articulate a plausible case for the existence of a superior alternative. It seems to me that the world would be a much better place if, whenever someone refused to accept either horn of a moral or political dilemma, they were expected to provide an explicit answer to the question "What would you do instead?" My impression is that activist groups often move us away from such a world rather than toward it.

Thanks for this, I think you articulate your point well, and I understand what you're saying.

It seems that we disagree, here:

My point is exactly that I don't think that a world with a very strong version of this norm is necessarily better. Of course, I agree that it is best if you can propose a feasible alternative and I think it's perfectly reasonable to ask for that. But I don't think that having an alternative solution should always be a requirement for pointing out that both horns of a dilemma are unacceptable in an absolute sense.

Sometimes, the very act of critiquing both 'horns' is what prompts us to find a third way, meaning that such a critique has a longer-term value, even in the absence of a provided short-term solution. Consequently, I think there's a downside to having too high of a bar for critiquing the default set of options.

To be clear, I think we both need the more 'activist' approach of rejecting options that don't meet certain standards, as well as the more 'incrementalist' approach of maximising on the margin. There's a role for both, and I think that Farmer did a great job at the former, while much of the effective altruism movement has done a great job at the latter. Hence why I found it valuable to learn about his work.

Thanks for your reply.

Yeah, this seems plausible to me, and is something I hadn't fully appreciated when I wrote my previous comment.

As a side note, I'm not familiar with Farmer's work, but this exchange (and Gavin's post) has motivated me to read Mountains Beyond Mountains.

I appreciate hearing that and I've appreciated this brief exchange.

And I'm glad to hear that you're giving the book a try. I expect that you will disagree with some of Farmer's approaches – as I did – but I hope you will enjoy it nonetheless.

In general, I think the more 'activist' approach can be especially useful for (1) arguing, normatively, for what kind of world we want to be in and (2) prompting people to think harder about alternative ways of getting there – this is especially useful if some stakeholders haven't fully appreciated how bad existing options are for certain parties. Note that neither of these ways to contribute requires concrete solutions to create some value.

Also, to add:

For example, we both need advocates to argue that it's outrageous and unacceptable how the scarcity funds allocated towards global poverty leaves so many without enough, as well as GiveWell-style optimisers to figure out how to do the most with what we currently have.

In a nutshell: Maximise subject to given constraints, and push to relax those constraints.

It's great you mentioned liberation theology. Here's some extra information since I've had some contact with it through social activism in Brazil:

These are great Gavin.

It's been a while since I worked on global development issues (largely focusing on NTDs back in 2014/15) but did Farmer not also help popularise the biosocial approach (which I thought had a large impact) ? No mention of 'biosocial' on the wiki page though.

Thanks for sharing. He’s been one of my heroes for a long time, and I see him as having both strong overlap with certain EA ways of thinking and serious differences.

He was a person who had an unswerving commitment to justice and improving human flourishing. He recognized the utter injustice of health inequalities and was able to articulate that vision so that it could be understood by many folks who don’t typically care about the suffering of far-off people who look different than them. These ways of thinking are central to EA for me: the sense that we have no right to discount the suffering of far-off individuals, no matter who they are or what they look like; the sense that we have serious moral obligations that require serious commitment.

He was also a person who situated medical problems within sociopolitical contexts, and who believed that comprehensive solutions (i.e., investing in health systems across the board) were far superior to targeted interventions (i.e., bed nets). He was critical of approaches focused on cost-effectiveness, arguing that they were morally abhorrent. In this sense, he is obviously taking a very different approach to the traditional EA approach. But I think that some of his arguments are valuable counters to the EA emphasis on targeted interventions,illustrating as they do that targeted interventions are subsidized by existing infrastructure, and that some initiatives–such as the Partners in Health campaign against multi-drug resistant TB in Peru–can be initially non-cost effective but eventually change market pressures and norms such that, in toto, they are incredibly cost-effective. Farmer’s work reminds us that assessments of cost-effectiveness must take into account that inputs are not stable, and that initiatives can be transformative, and that if we zealously focus on short-term effects, we will miss out on opportunities for transformative change.

I don’t agree with everything that Farmer stated or fought for. But I think the EA community would benefit from the insights from his life and work. Paul Farmer is worthy of the utmost respect for his unwavering commitment to improving the lives of marginalized people, and his death is a tragic loss.

Thanks for writing this. PIH and Paul's work were a big inspiration to me, and were one of my early exposures to two ideas that are essential to EA: one, that people matter just as much no matter where they are or how hidden their suffering is from me; and two, that my money earmarked for helping people will go so, so, so much farther investing in the health and wellbeing of the poorest of the poor than in causes that may be more visible to me.

I have a couple of lessons that I learned from PIH and Paul Farmer that I will attempt to apply to my life as a whole and my EA thinking and action. These lessons are meant for me, to solidify my thinking and write something I could remind myself with, but I thought I would share my takeaways with the community as well.

1) Sometimes, you have to change your level of perspective to truly understand what the most effective use of time, resources, etc is. When Paul and PIH were faced with multi drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Peru, they were told by the WHO, the medical community, and the government over and over that it was too expensive- better to spend the money on lots of cheap drugs to treat lots of sick but curable patients than to spend it all on a few very sick patients. This math is important to do, and we must factor in the opportunity cost when using our resources; we owe it to the people whose suffering our money, time and energy could help to grapple with and make decisions about who and how to spend it to maximize the effectiveness. However, it is also true that sometimes, a proof of concept that you can indeed treat a disease, albeit at great cost, can lead to a mobilization to lower the cost. People get energized by a problem of degree, and get discouraged by a problem of impossibility. People who do the impossible at great cost are invaluable.

2) Listen, ask questions, and listen some more. When you feel like you've listened enough, that's a good signal that you should listen some more. There are things you know; there are things you don't know but can learn; and there are things which it's just better to leverage someone else's knowledge. Paul was a Harvard-trained MD and PhD, with extensive experience in poor, rural healthcare, who spoke fluent French and Creole. And yet, he still relied heavily on local knowledge and experts. This was not done to make his organization more diverse, or to cloak his ideas in the voice of the locals, but because that partnership made him more effective at treating the health of his patients. He listened so much that it was a superpower. This is a lesson that I have learned and relearned, and will have to learn again.

3) It takes all kinds. I am not religious, Paul was motivated explicitly by religious ideas. EA looks at cost per DALY and QALY (among other things, of course), PIH looked at each human life as worthy of the best medical care and support that money could buy. It is important to be true to your values, but it is also important to shun the narcissism of small differences. Find ways to make the world a better place, celebrate those who are, make making the world a better place something more people (with all sorts of different motivations) want to do, and make making the world a better place more and more effective.

4) Inspiring others can truly be a massive impact. The sheer number of my classmates who were inspired to pursue a career in public health because of Paul Farmer and PIH was truly amazing to me. Personally, however, I actively shut myself down from oversharing my own "good deeds". In my younger days, I bragged, lied, and used my intelligence to bullshit. An essential part of growing up for me has been to develop an allergy to my own bragging, to be comfortable with who I am and let my actions speak for themselves. I think something I will have to continue to struggle with is when and how to share in a way that normalizes doing good, without it being about stroking my own ego or gaining praise and recognition. This is something I haven't fully figured out yet, but I am working on it and getting better.

5) The best in anything have most of the impact. 80k's conventional wisdom is not to go into medicine, or if you do, work in a rich country and donate your salary. And yet this man is one of the most successful people at improving the world in the past half century. People like Paul Farmer do not come around every day, and it is good to give advice that helps drastically improve the good an average life can do; 80k people will say this too, that their top cause areas may be good on average but specifically your best potential impact has a lot to do with you, what makes you tick, what you have an advantage in. That said, we can do more as a community and I can do more individually to take and encourage others to take the idea of being the best at whatever you're the best at, and using that bestness to improve the world.

Thanks for this! I just wanted to recommend the documentary movie about his work 'Bending the Arc', which is on netflix.

Thank you for the reminder to watch Bending the Arc. There were also some moving tributes to him (with excerpts of his interviews) on Twitter after he passed, such as this one from Ava DuVernay.

Thanks for writing this! It's interesting that PIH chose not to disclose their outputs and be evaluated given that they seem to be (at least it's my perception) very on-the-ground and impact orientated. Hopefully, that will change. Also - it was mentioned, but I highly recommend Mountains Beyond Mountains.

Thank you for writing this. Learning about people like Farmer is hugely inspiring and the last two quotes you included made me surprisingly emotional. It really gives a sense for how deeply committed Farmer was to his work and makes me want to raise my own aspirations when it comes to improving the world.

A different register

https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2022/03/in-praise-of-paul-farmer.html

At min, his life is as much a marvel to praise as it is a bit of a tragedy. Like a true altruist, he quite literally worked himself to death for the good of others. Even if his methodologies weren’t always the most effective, there are very few who will be able to match his degree of selfless sacrifice.

I think his friends and Farmer himself would disagree with you- he loved what he did, felt like he could not do otherwise. He was also always smiling, laughing, and joking. His memorial service is on youtube, both of his cofounders talked about his sense of humor and his love for the work he was involved in. I think a life lived happy and in the service of improving the world is about the farthest possible from a tragedy, even if it is shorter than average