[Crossposted from my Substack, Unfolding Atlas]

How will AI get us in the end?

Maybe it’ll decide we’re getting in its way and decide to take us out? It could fire all the nukes and unleash all the viruses and take us all down at once

Or maybe we’ll take ourselves out? We could lose control of powerful autonomous weapons, or allow a 21st century Stalin set up an impenetrable surveillance state and obliterate freedom and progress forever.

Or maybe the diffusion of AI throughout our global economy will become a quiet catastrophe? As more and more tasks are delegated to AI systems, we mere humans could be left helpless, like horses after the invention of cars. Alive, perhaps, but bewildered by a world too complex and fast-paced to be understood or controlled.

Each of these scenarios has been proposed as a way the advent of advanced AI could cause a global catastrophe. But they seem quite different, and warrant different responses. In this post, I describe my model of how they fit together.[1]

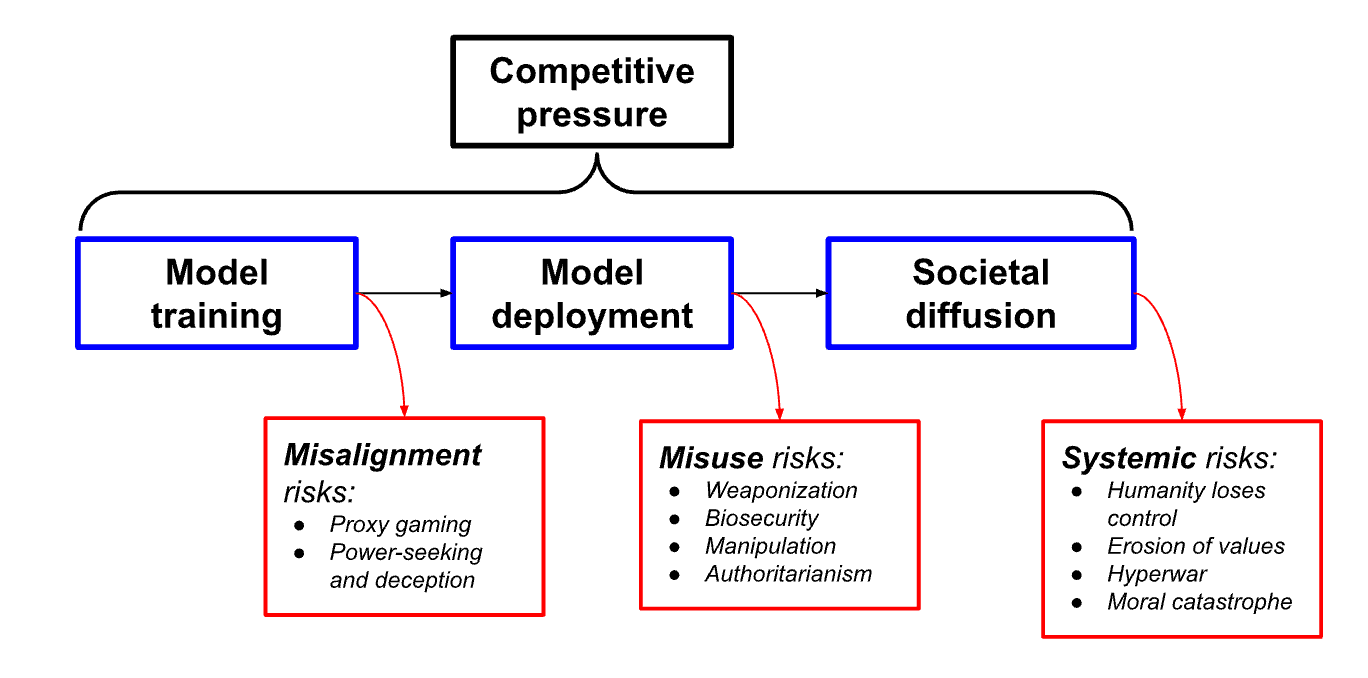

I divide the AI development process into three steps. Risks arise at each step. Despite its simplicity, this model does a good job pulling all these risks into one framework. It’s helped me understand better how the many specific AI risks people have proposed fit together. More importantly, it satisfied my powerful, innate urge to force order onto a chaotic world.

Terrible things come in threes

The three AI development stages in my model are training, deployment, and diffusion.

At each stage, a different kind of AI risk arises. These are, respectively, misalignment, misuse, and systemic risks.

Throughout the entire process, competitive pressures act as a risk factor. More pressure makes risks throughout the process more likely.

Putting it all together looks like this:

This model is too simple to be perfect. For one, these risks almost certainly won’t arrive in sequence, as the model implies. They’re also more entangled than a linear model implies. But I think these shortcomings are relatively minor, and relating categories of risk like this gives them a pleasant cohesiveness.[2]

So let’s move ahead and look closer at the risks generated at each step.

Training and misalignment risks

The first set of risks emerge immediately after training an advanced AI model. Training modern AI models usually involves feeding them enormous datasets from which they can learn patterns and make predictions when given new data. Training risks relate to a model’s alignment. That is, what the system wants to do, how it plans to do it, and whether those goals and methods are good for people.

Some researchers worry that training a model to actually do what we want in all situations, or when we deploy it in the real world, is far from straightforward. In fact, we already see some kinds of alignment failures in the world today. These often seem silly. For example, something about the way Microsoft’s first Bing chatbot’s goal of being helpful and charming actually made it act like an occasionally funny, occasionally frightening psychopath.

As AI systems get more powerful, though, these misalignment risks could get a whole lot scarier. Specific risks researchers have raised include:

- Goal specification: It might be hard to tell AI systems exactly what we want them to do, especially as we delegate more complicated tasks to them. Some researchers worry that AIs trained on large amounts of data will either end up finding tricks or shortcuts that lead them to produce the wrong solutions when deployed in the real world. Or that they’ll face extreme or different situations in the real world than they saw in the training data, and will react in unexpected, potentially dangerous, ways.

- Power-seeking and deceptive behavior: Advanced AI systems may realize that, whatever goal they have, having power will be useful. They may further realize that, if their human operators know that they know this, they’ll shut the system down. This could lead to a scenario where an advanced AI cooperates at first, and then takes control of various global systems once it is able to do so.

Misalignment scenarios often involve building AIs that pursue goals not related to human well-being. If such an AI was sufficiently powerful, it could take over and eliminate or disempower humanity as part of its plan to achieve its goals.

Deployment and misuse risks

After training comes deployment.

Let’s assume that we can train aligned systems. We have powerful AIs that reliably do what we want. We still won’t be in the clear. The next challenge we’ll face is misuse risks: how will we ensure everyone, everywhere, uses these systems responsibly?

AI systems will probably be applied to a vast range of problems. Most of those applications will be great, helping us solve complex problems and provide amazing goods and services, including things we can’t even imagine today.

But people could also use them to cause harm. And the power of these systems mean that they could be used to do a lot of harm. Such misuse risks may take several different forms:

- Weaponization: AI-enhanced drones are becoming an increasingly important weapon for both warfare and assassinations. AI systems could control huge swarms of drones to quickly kill enormous numbers of people.

- Biosecurity: Some experts worry that advanced AI will make it much easier for people to make bioweapons. The falling cost of biotechnology makes it more plausible that this knowledge can actually be used for destructive purposes.

- Propaganda and Manipulation: AI systems may be used to generate large amounts of persuasive propaganda, perhaps tailored to each individual, damaging democratic institutions.

- Authoritarian lock-in: The ability to process large amounts of audiovisual data make AI systems a boon for leaders seeking to closely surveil their population. Some experts worry that ironclad surveillance could allow authoritarian regimes to entrench themselves, risking a lock-in of their values.

This list probably isn’t exhaustive. We’re still learning what large language models alone are capable of. As we train more powerful and more diverse AIs, we’ll learn a lot about these systems can do. We’ll discover more ways to use AIs — and more ways to misuse them.

Diffusion and systemic risks

Finally, let’s assume that we’ve managed to train AI systems that basically do what we want, and that we’ve built defenses to stop people from using them to do massive harm. We’ll still face a challenging transition to a world in which AI systems play an important role in our global systems.

This transition could be both extremely dramatic and extremely quick. Think a century of progress occurring in just a few months or years. We could majorly screw it up. The risks here seem more subtle, but potentially just as serious as the more obvious disasters above.

- Value erosion: AI systems will be useful. That’s why we’re building them. So people, companies, and other institutions like militaries will be incentivized to use them. Those that don’t will lose out to competitors that do, just as a trade today who didn’t use technology to execute trades at lightning speed would be at a big disadvantage.

Over time AIs will perform a larger share of socioeconomic tasks and decisions. But if it proves difficult to fully describe what exactly we want these AIs to do, we could end up missing out on important things we value. AI safety researcher Paul Christiano has noted that this increasing ability to “get what we measure” could cause a “slow-rolling catastrophe”: AI-powered companies increasing profits through consumer manipulation and AI-powered governments winning elections through voter manipulation. Dan Hendrycks has also argued that evolutionary pressures favor selfish AIs over benevolent ones. - Loss of control: Handing control of important systems to AIs will raise other issues. For example, AIs are able to think and act much faster than people can. This could make it difficult for people to oversee AI decision-making, and intervene if it seems like things are going wrong. Without prudent coordination or regulation, organizations that do maintain human oversight risk losing out to more risk-seeking competitors that don’t.

Eventually entire industries may be automated: AI executives will run AI companies and sell AI products to AI customers. Complex, closed-loop economies could form entirely outside human control and prove difficult to shut down. - Hyperwar: The risk of losing control is particularly stark in the military realm. Integrating AI systems into militaries could increase the speed at which war is fought. It would become harder for humans to contribute to strategic and tactical decision-making. It could also enable very rapid escalation. In the financial realm, interactions between automated trading systems have led to flash crashes, changing asset values far faster than human traders could have. Future wars could escalate similarly quickly, growing to catastrophic size before humans can intervene and de-escalate.

- Moral catastrophe: A final, wild possibility is that we could cause a moral catastrophe by mistreating AIs. Advanced AI systems will likely display complex sensing, information processing, and decision-making abilities. It seems at least plausible that some of these abilities are related to the phenomenon of consciousness. This raises the possibility that, in the future, AIs themselves will warrant moral concern.

The Industrial Revolution, competitive economic dynamics, and a lack of concern for animal rights allowed for a massive expansion in intensive farming systems. The moral implications of this are controversial, to say the least, but it is at least plausible that the negative effects for farmed animals partially offset the widespread welfare gains for people. The future will probably see a similar explosion in the number of AI systems. We could make the same mistake again. To create and condemn huge numbers of conscious beings to an unpleasant or even torturous existence would seem to warrant being called a moral catastrophe.

You don’t have to make crazy assumptions to think that a world with widespread superintelligent AIs will be very strange. Whether it will also be very good is more uncertain.

Risk factor: Competitive pressure

A skeptical critic might ask why companies would release misaligned AI systems or allow customers to misuse them, or why governments would allow systemic risks to arise. These are fair questions. I do expect to see these organizations make strong technical and legal efforts to avoid these worst-case scenarios.[3]

However, it’s also worth recognizing how competition will shape incentives at each stage of the development process.

AI companies will face strong incentives to develop powerful models before their competitors. Evaluating models, especially large, complex ones, for dangerous capabilities will take time. There will be strong pressure to speed up or shorten the evaluation process to avoid being beaten to the market by other companies.

In fact, we’ve already seen this play out. The creepy AI-powered Bing search I mentioned earlier was rushed out by Microsoft after they saw how much hype OpenAI’s ChatGPT was garnering. As AI systems get more powerful, their economic value will also increase, perhaps further increasing these pressures.

The same dynamics could apply to misuse risks. Companies may avoid building explicitly-harmful AIs. But AI systems can be applied to a wide range of problems. Tuning them to filter out harmful outputs could take time - time in which a competitor could beat them to market.

Finally, we saw how competitive dynamics can drive systemic risks as various actors seek an edge by handing more control over to AI systems.

None of these risks seems inevitable. All can be avoided by combining technical solutions and regulatory coordination. But those solutions won’t be created and implemented automatically. Designing and implementing responsible policies at the firm, national, and international level will be a lot of work. Meanwhile, AI progress will, by default, continue. The path of least resistance is a treacherous one.

Conclusion

Modeling AI development as a three-stage process — training, deployment, and societal diffusion — has helped me understand how the different AI risks people have proposed fit together.

It’s too simple to model AI development perfectly. For one, it’s too linear; we could face catastrophic misuse risks before catastrophic misalignment risks if less powerful systems can be used for nefarious purposes. Or we may face risks from the different categories simultaneously. And in some cases the boundaries are a bit blurry. The ways a misaligned AI could wreak havoc could be the same ways a person could misuse AI systems: like attacking digital infrastructure or unleashing powerful weapons.

On the whole, though, this model stitches together what otherwise seem like quite different risk pathways. I’m not aware of any major AI risk proposals that aren’t mentioned here or couldn’t fit into this model — though if there are I’d love to hear about them!

- ^

I’m only focusing on global, generational risks. These are clearly not the only important effects of advanced AI systems. There are other kinds of risks: algorithmic biases, supporting spam and scam artists, economic upheaval. And there will, of course, also be many benefits: scientific discoveries, better decision-making, freedom from boring administrative and logistics tasks, more efficient manufacturing. Although this post is a bit of a downer, I think the upside is large. Once we know how to safely develop these systems we probably should.

- ^

Other classification schemes include Hendrycks, Mazeika, Woodside’s “An Overview of Catastrophic AI Risks” and Critch and Russell’s “TASRA: a Taxonomy and Analysis of Societal-Scale Risks from AI”.

- ^

Stefan Schubert has called the tendency to ignore potential adjustments in response to future risks sleepwalk bias.

You may have also seen Sam Clarke's classification of AI x-risk sources, just sharing for others :)

Wei Dai and Daniel Kokotajlo's older longlist might worth perusing too?

Yes; it could be useful if Stephen briefly explained how his classification relates to other classifications. (And which advantages it has - I guess simplicity is one.)

This is a very informative article. The three stage model simplifies the risks for better understanding of what would happen. The alignment stage is a very crucial stage in AI development and deployment. All the risks in all the three stages are equally very catastrophic. We could never be 'ready for what is to come' but we could surely curb it at the alignment stage!

Thank you for the piece!

Executive summary: AI development involves risks at three key stages: training (misalignment), deployment (misuse), and diffusion (systemic issues). Competitive pressures exacerbate risks across all stages.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.