My main question

The EA Funds Animal Welfare Fund makes grants to many different animal charities. Suppose I want to support one particular charity that they grant to because I think it's better, relative to my values, than most of the other ones. For example, maybe I want to specifically give to Legal Impact for Chickens (LIC), so I donate $1000 to them.

Because this donation reduces LIC's room for more funding, it may decrease the amount that the Animal Welfare Fund itself (or Open Philanthropy, Animal Charity Evaluators, or individual EA donors) will give to LIC in the future. How large should I expect this effect to be in general? Will my $1000 donation tend to "funge" against these other EA donors almost fully, so that LIC can be expected to get about $1000 less from them? Is the funging amount more like $500? Is it roughly $0 of funging? Or maybe donating to LIC helps them grow faster, so that they can hire more people and do more things, thereby increasing their room for funding and how much other EA donors give to them?

The answer to this question probably varies substantially from one case to the next, and maybe the best way to figure it out would be to learn a lot about the funding situation for a particular charity and the funding inclinations of big EA donors toward that charity. But that takes a lot of work, so I wonder if EA funders have some intuition for what tends to happen on average in situations like this, to inform small donors who aren't going to get that far into the weeds with a particular charity. Does the funging amount tend to be closer to 0% or closer to 100% of what an individual donor gives?

I notice that the Animal Welfare Fund sometimes funds ~10% to ~50% of an organization's operating budget, which I imagine may be partly intentional to avoid crowding out small donors. (It may also be motivated by wanting charities to diversify their funding sources and due to limited funds to disburse.) Is it true in general that the Animal Welfare Fund doesn't fully fill room for funding, or are there charities for which the Fund does top up the charity completely? (Note that it would actually be better impact-wise to ensure that the very best charities are roughly fully funded, so I'm not encouraging a strategy of deliberately underfunding them.)

In the rest of this post, I'll give more details on why I'm asking about this topic, but this further elaboration is optional reading and is more specific to my situation.

My donation preferences

I think a lot of EA donations to animal charities are really exciting. About 1/3 of the grants in the Animal Welfare Fund's Grants Database seem to me roughly as cost-effective as possible for reducing near-term animal suffering. However, for some other grants, I'm pretty ambivalent about the sign of the net impact (i.e., whether it's net good or bad).

This is mainly for two reasons:

- I'm unsure if meat reduction, on the whole, reduces animal suffering, mainly because certain kinds of animal farming, especially cattle grazing on non-irrigated pasture, may reduce an enormous amount of wild-animal suffering (though there are huge error bars on this analysis).

- I'm unsure if antispeciesism in general reduces net suffering. In the short run, I worry that it may encourage more habitat preservation, thereby increasing wild-animal suffering. In the long run, moral-circle expansion could encourage people to create lots of additional small-brained sentience, and in (hopefully unlikely) scenarios where human values become inverted, antispeciesist values could multiply total suffering manyfold.

If I could press a button to reduce overall meat consumption or to increase concern for animals, I probably would. In other words, I think the expected value of these things is perhaps slightly above zero. But my expected value for them is sufficiently close to zero that I don't feel great about my donations being used for them.

Therefore, I would prefer to not spend precious money to support alternative proteins, veg outreach, or expanding the general animal-advocacy movement. Rather, the work I'm most excited about is welfare reforms -- especially for the most numerous animals like chickens, fish, and shrimp, and especially those reforms that reduce the very most intense suffering, such as the pain of slaughter.

(By the way, I would definitely press a button to reduce chicken consumption, but I plausibly would not press a button to reduce beef consumption. I wish it were feasible to push on one but not the other of these variables, but that seems tricky to do as a donor, other than maybe by giving to One Step for Animals.)

Donation funging

The specificity of my preferences regarding which animal activism I'm enthusiastic about makes it harder to find good donation targets. Most animal charities do a mix of welfare reforms, meat reduction, and moral-circle expansion. Earmarking your donation for one of these activities in particular could allow the charity to funge your donation by spending less of their unrestricted money on that activity (although in some cases, earmarked donations go toward new projects that wouldn't have happened at all otherwise).

There's a similar kind of funging between charities, especially in contexts like EA where donors are sensitive to room for more funding (Shulman 2014). Donating to a single charity is kind of like making an earmarked donation: it frees up other EA donors to use their "unrestricted" money for all the other EA animal charities instead. This funging concern has been discussed by a number of authors, such as Budolfson and Spears (2019). The thrust of my question is: Does this actually occur a lot in practice in the EA animal-welfare world? Or is it mainly a theoretical worry?

The concern is that if I donate to, say, Legal Impact for Chickens, then the Animal Welfare Fund will donate less to that charity and have more money for other things. In the worst case where there's 100% funging, my donation to LIC is only as good as donating to the Animal Welfare Fund itself, which splits its grants between welfare reforms and other activities that I'm less interested in. Maybe the average Animal Welfare Fund grant is only 1/3 to 1/2 as good as a grant to a specific charity that I want to support, so in the case of 100% funging, the effectiveness of my donation by my lights would be multiplied by 1/3 to 1/2.

Donating to less popular targets

One possible answer to the funging problem is to seek charities or other funding opportunities "off the beaten path", i.e., ones that the big EA animal donors probably wouldn't fund. AppliedDivinityStudies (2021) also makes this suggestion.

One way to do this is to look for individual activists whom you know personally but who are unlikely to receive institutional EA funding, such as because the grant size would be too small to bother with or because the activism isn't legible to or suited to the tastes of the bigger EA funders. However, the total amount of gifts you can make this way may not be very high unless you know a lot of activists in this category.

Another approach is to give to charities that aren't popular with other EAs. I donate a bit to Animal Ethics (AE) because it doesn't receive much funding from the big EA donors. AE's last grant from the Animal Welfare Fund was in 2018, and Animal Charity Evaluators stopped highlighting AE as a Standout Charity in 2017. AE's focus on wild-animal suffering makes it less likely that AE's particular brand of moral-circle expansion will increase support for wilderness preservation. That said, I'm more enthusiastic about specific welfare reforms that will reduce suffering in the near future, which AE doesn't really work on. My reason for donating to animal causes at all is because they're more concrete than nebulous far-future suffering-reduction work, so the more tangible the impact is, the better.

The Humane Slaughter Association (HSA) is another option that not many EAs seem interested in. HSA received two large grants from Open Philanthropy, in 2017 and 2019, but those were earmarked for specific projects, so general HSA funding may not be funged by them. HSA meets most of the criteria I'm looking for: it only does welfare reforms, it doesn't mention environmentalism, and it focuses on the most extreme suffering (slaughter), including of chickens and fish. The main downside of HSA for me is that a lot of its work targets larger animals (cattle, pigs, etc), which are numerically less important. If only, say, 1/3 to 1/2 of HSA's work is about chickens and fish, then the impact of a donation to it is sort of multiplied by 1/3 to 1/2, similar to what I mentioned regarding donating to the Animal Welfare Fund. I suppose one could ask HSA to earmark a donation toward a fish-specific project, as Open Philanthropy did, but this would be a lot of work for a small donor like me. And that fish-specific project would be more likely to funge against future Open Philanthropy grants.

HSA has for many years had a large fund of assets that it invests rather than spending, which may lead people to conclude that it lacks room for more funding. I'm not sure if that's accurate, since investing money to spend later is a reasonable strategy to take, both for individuals and organizations. HSA has existed since 1911, so it's not in growth mode the way a startup charity would be. Donating more than what a charity can spend now doesn't seem to me like a problem per se; the problem is when that surplus of funding discourages other donors from giving to the charity.

Charities that aren't adored in EA can still have their own forms of funging with non-EA donors. Some non-EA would-be donors might think these charities already have enough funding and give elsewhere. But that seems less likely than in the case of big EA donors who actively scrutinize room for more funding and aren't as emotionally attached to one particular organization.

If having lots of money makes a charity less interested in fundraising, that could be another way in which donations to more obscure charities can be funged. (Holden Karnofsky makes this point in the comments on Shulman (2014).)

Closing remarks

I'm curious whether readers have suggestions for additional animal-welfare charities meeting my criteria that wouldn't by default be funded by the big EA donors. Maybe the Animal Welfare Fund could share a list of charities they almost funded but that didn't make their cutoff and that they're unlikely to fund in the future either. Or a list of which of the charities they are funding still have significant room for more funding that the Animal Welfare Fund doesn't expect to fill in the future.

I certainly wouldn't want to discourage people from donating to the Animal Welfare Fund; I consider donating to it myself. I think some of the work it funds is amazing and some is at worst ~neutral in expectation. By my lights, it would be bad if people donated less to animal charities and more to other EA causes -- especially something like biorisk reduction, which I think increases expected future suffering, though like with everything else, the sign is very unclear. This problem of funging between EA cause areas (including cause areas that are net good and net bad according to my values) is an additional layer of vexation.

Your question is fairly relevant to the discussion because if I thought there was net positive value in the lives of wild animals, then I would have a lot fewer concerns about non-welfare-reform animal charities.

I've had it on my todo list to check out that video and paper, but I probably won't get to it any time soon, so for now I'll just reply to the slides you asked about. :)

Personally I would not want to live even as the two surviving adult fish, because they probably experience a number of moments of extreme suffering, at least during death if not earlier. They may be fearful of predators, they face unpleasant temperatures or other bad environmental conditions without being able to control them the way humans do with air conditioning and heating, they may face long periods of low food, there might be intraspecific aggression and sexual harassment (I don't know if those behaviors apply to Atlantic cod, but they are common in some fish species), and there would be many other hardships. Most of these moments of suffering probably wouldn't feel that bad, but a few of them might be unbearably awful.

I said that I "personally" wouldn't want to live as one of these surviving fish, but you might say that the real question is whether they would want to have these lives rather than not existing. We can't ask fish that question, but if we imagine humans having similar lives as these fish, we could ask such humans that question. Maybe many of those humans would say during many moments of their lives that they were on balance glad to exist. However, I suspect that during some moments, such as the peak pain of dying, they would often change their minds and wish they hadn't existed. Therefore, there's no single individual whom we can ask whether his/her life was net positive; there are multiple "individuals" within the animal's life, some of whom are glad to exist and some of whom are horrified to exist. How we weigh up these conflicting opinions is ultimately a judgment call, and no amount of further empirical data on wild-animal welfare will resolve it. I take a suffering-focused approach to this dilemma and say that it's not acceptable for the happier moments of the animal's life to impose unbearable suffering on some other moments of the animal's life. So for any animal that has moments of unmitigated, unbearable agony (as most animals do, if only when dying), its life is net negative in my view.

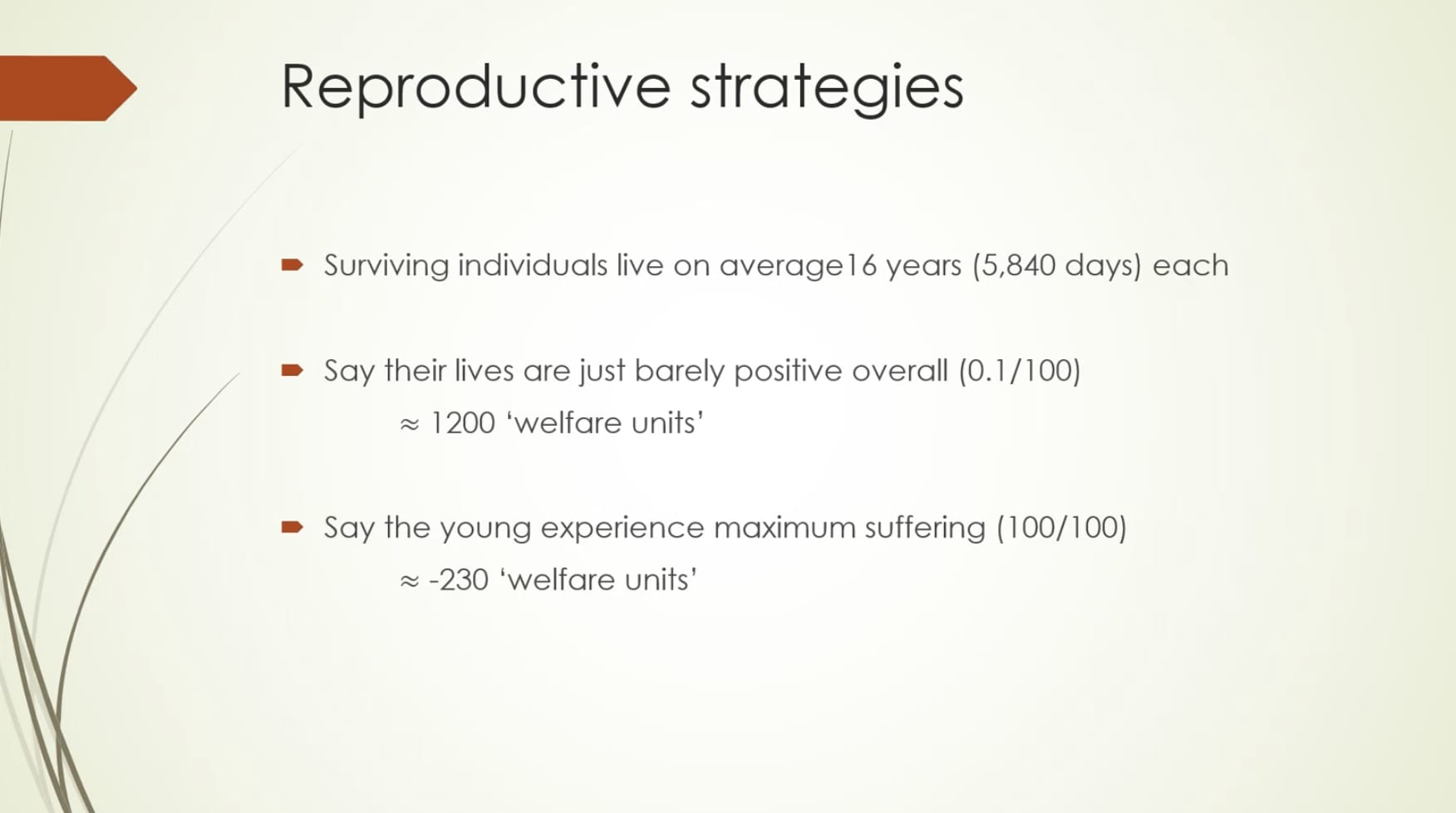

But most people don't take this suffering-focused approach. Many people think enough happy moments of life can outweigh something as awful as being eaten alive. So next I'll discuss the specific numbers in those slides.

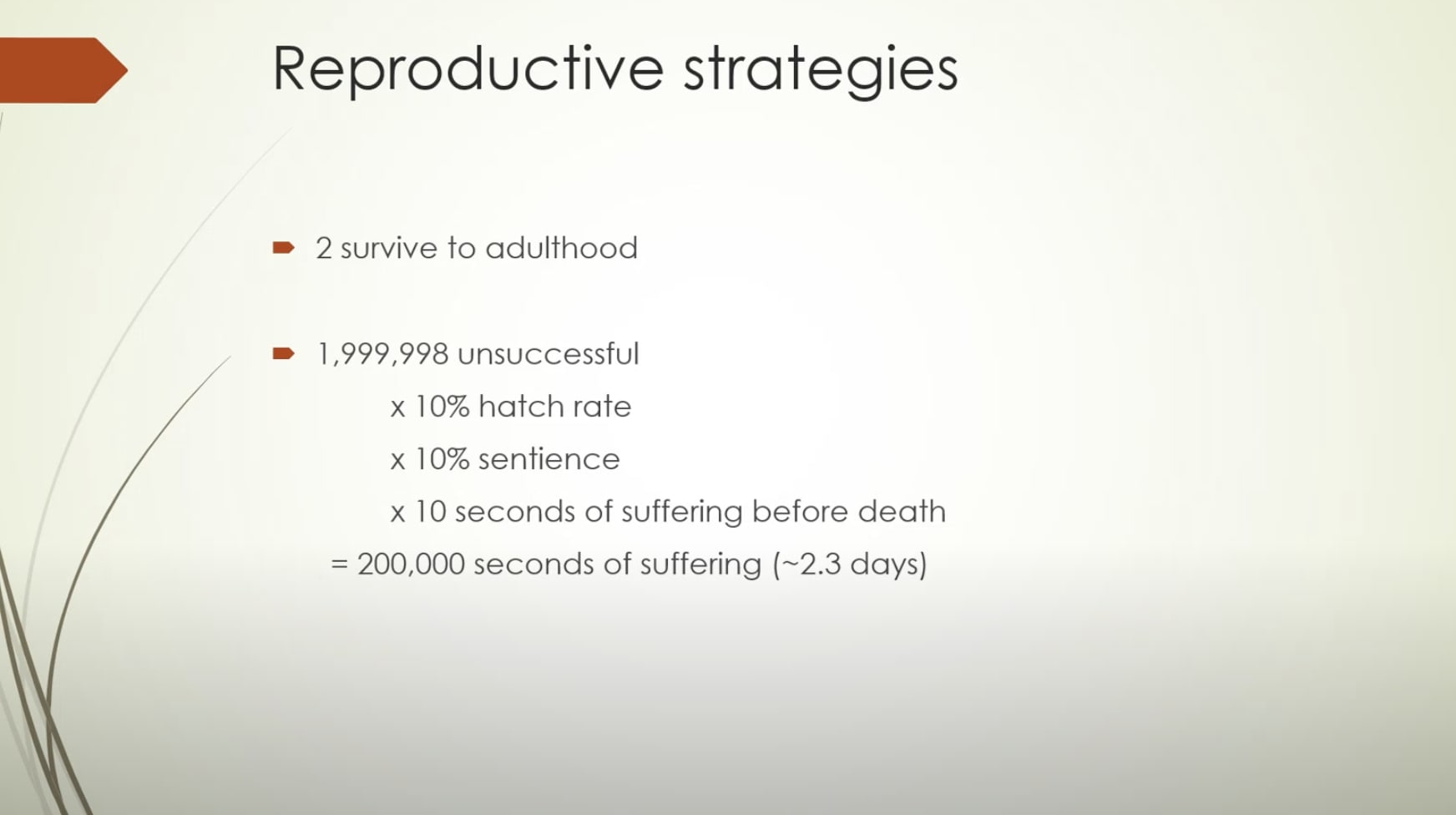

If a baby fish is only enduring 10 seconds of agony when dying, as the first slide suggests, then it's presumably dying from predation (or maybe a severe physical injury like being crushed or something). The next slide suggests that maybe the pain of predation is 100/100, compared against a presumed positive welfare of 0.1/100 for ordinary life. So getting eaten alive is only 1000 times worse than the goodness of a typical moment of life. That might seem plausible if we only glance at the numbers, but it's not at all plausible if we actually think about what it implies. Imagine that you endure getting eaten alive for 1 minute. These numbers say that a mere 1000 minutes of ordinary life could compensate for that. 1000 minutes is 16.7 hours, slightly more than the amount of time a typical person is awake in a day. So this ratio says that even if you spend a minute every day experiencing what it's like to be eaten alive, then your life can still be welfare-neutral. I wonder if anyone would actually sign up for that. One of the least suffering-averse trade ratios I've heard someone endorse was that he'd be willing to experience being eaten alive for an extra week of life (IIRC; that conversation was a long time ago). (I guess there are also a few people who say even more extreme things like "I'd rather be alive and tortured forever than not exist", though I expect they'd change their minds pretty quickly when the torture started.)

One possible argument is that it's illegitimate to rely on our human intuitions about this tradeoff, because r-strategists may have evolved different pain-pleasure trade ratios based on the situation they face. For example, almost all fish babies will die by default, so if there's an opportunity to take a dangerous risk in order to gain some slight advantage, they should probably take it, since they have almost no chance of winning otherwise. Therefore, maybe they need to be less averse to suffering (or at least less afraid of suffering) than we would be. This might be the case, but it's a very theoretical argument, so I'm wary of putting too much stock in it. Of course, any estimate we have of how much suffering and pleasure exist in nature will be very speculative, so if I were a classical utilitarian who thought a minute of extreme suffering might be outweighable by a few days, weeks, or months of ordinary life in the wild, then I would have some uncertainty about the net hedonic balance of nature. But in my own case, I don't think it's ok to force extreme suffering on one for the pleasure of another -- much less imposing extreme suffering on 1,999,998 for the pleasure of 2. (If we assume a 10% hatch rate and a 10% chance of sentience, then this comparison is actually 19,999.98 vs 2. And if we look at individual organism-moments of experience, the 2 surviving fish have a lot of organism-moments.)

As I mentioned, the slides seem to be assuming deaths by predation given how short the duration of suffering is. Death by almost anything else would probably take hours, days, weeks, etc, although the intensity of pain during that time would usually be a lot lower than the intensity of pain during predation. This article says:

So maybe rather than 10 seconds, the period of pain while dying should be measured in hours or days? 1 day = 86,400 seconds. Of course, the badness of most of those seconds would be a lot less than 100/100.

See also: "Is There More Suffering Than Happiness in Nature? A Reply to Michael Plant".