Crossposted from my blog which many people are saying you should check out!

Imagine that you came across an injured deer on the road. She was in immense pain, perhaps having been mauled by a bear or seriously injured in some other way. Two things are obvious:

- If you could greatly help her at small cost, you should do so.

- Her suffering is bad.

In such a case, it would be callous to say that the deer’s suffering doesn’t matter because it’s natural. Things can both be natural and bad—malaria certainly is. Crucially, I think in this case we’d see something deeply wrong with a person who thinks that it’s not their problem in any way, that helping the deer is of no value. Intuitively, we recognize that wild animals matter!

But if we recognize that wild animals matter, then we have a problem. Because the amount of suffering in nature is absolutely staggering. Richard Dawkins put it well:

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute that it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive, many others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear, others are slowly being devoured from within by rasping parasites, thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst, and disease. It must be so. If there ever is a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in the population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored.

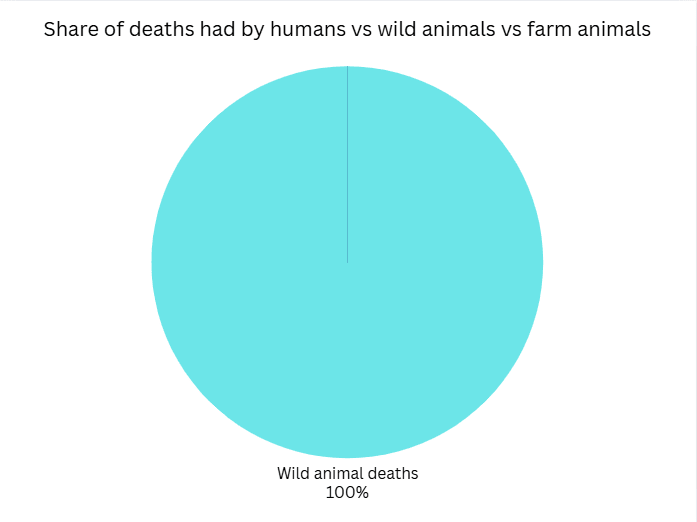

In fact, this is a considerable underestimate. Brian Tomasik a while ago estimated the number of wild animals in existence. While there are about 10^10 humans, wild animals are far more numerous. There are around 10 times that many birds, between 10 and 100 times as many mammals, and up to 10,000 times as many both of reptiles and amphibians.

Beyond that lie the fish who are shockingly numerous! There are likely around a quadrillion fish—at least thousands, and potentially hundreds of thousands of times more numerous than people. Terrestrial arthropods—creatures like shrimp and crabs—number somewhere between 10^17 and 10^19, meaning that there could be ten million of these creatures for every human. And other creatures, like kinds of worms, are even orders of magnitude more numerous than that!

Additionally, I think that we have reason to care about the pain of such creatures, if, indeed, they can feel pain. When I reflect on what makes pain seem bad—what makes it bad to be in excruciating physical agony—it doesn’t seem to have to do with how smart the sufferer is. When you have a really bad headache, that’s not bad because you can do calculus. It’s bad because it hurts!

Call this the hurtfulness thesis. This says that pain is bad because it hurts—because it feels bad. This would imply that pain in wild animals is also bad because animals’ pain hurts them just as our pain hurts us! Various people have proposed alternatives to this, but they’re all really implausible.

- Maybe you think that pain is bad because it hurts creatures that are smart. Our pain is only bad on this picture because we’re very smart. But then this would imply that the pain of babies and the severely mentally disabled doesn’t matter much.

- Perhaps pain is bad because it hurts creatures that are members of our species. But then this implies that if we came across aliens who were very smart, then we could torture them for trivial benefit because their pain isn’t bad.

- Perhaps pain is bad because it hurts creatures that are members of smart species. But then this implies that if there was an entire species that remained permanently like a human baby, their pain wouldn’t be bad—we could hurt and injure them for trivial benefit. Hurting babies would only be wrong, on this picture, because human babies usually grow out of this state. Similarly, it implies that if we discovered that some mentally disabled people were technically not human, but were instead were, say, created by a machine without human DNA, then their pain wouldn’t matter. But this is ridiculous. The badness of your pain doesn’t depend on your species.

- Maybe pain is bad because it hurts those we have social contracts with. But this implies that if a hermit was in intense agony, this wouldn’t be bad, as they’re outside of society. Similarly, it implies that if there was an entire alien civilization that we could affect but who couldn’t affect us, causing them extreme agony wouldn’t be bad.

But if pain matters because it hurts, then wild animal suffering is worth taking seriously because there’s just so much of it! If every deer, pigeon, fish, and shrimp that cries out in pain as it’s eaten alive is a genuine tragedy, then the fact that this biological death machine consigns numbers of animals too great to fathom to an early grave is quite serious.

Most animals in nature live relatively short lives of intense suffering. Biologists distinguish between K-strategists—animals like humans and kangaroos who give birth to a few offspring and take care of them—and R-strategists, who give birth to huge numbers of offspring, very few of whom survive very long. Most animals are R-strategists; this means that almost every animal who has ever lived will have a very brief life culminating in a painful death.

If you only live a few weeks and then die painfully, probably you won’t have enough welfare during those few weeks to make up for the extreme badness of your death. This is the situation for almost every animal who has ever lived.

Even putting aside the situation for R-strategists, animals in the wild suffer a variety of forms of intense suffering. Just like humans were constantly getting horrific diseases before the dawn of medicine and sanitation, animals in nature are constantly getting extremely ill. Food is scarce, thirst and starvation are common, weather conditions leave them in constant profound discomfort, and natural disaster often lead to their horrible deaths. Animals in the wild are constantly on the run from predators, leaving them constantly terrified, and often the victims of an extremely painful death at the hands of a predator. Some have even theorized that PTSD is the default state for animals in nature. Animals who are not constantly vulnerable to predators tend to be much less nervous than ones who are. This isn’t surprising; you’d probably be nervous if a race of cannibals was constantly trying to eat you.1

Now, perhaps you doubt that the wild animals that I’ve cited really can suffer. Maybe you’re skeptical that shrimp and fish matter very much, and so you don’t think wild animal suffering is that serious. I think this isn’t a good reason to neglect wild animal suffering:

- I’ve elsewhere made the case for caring a good deal about shrimp. Our best evidence says that they can suffer, and probably pretty intensely. Additionally, pain is probably quite widely distributed across the animal kingdom—even small weird ocean worms probably can suffer. Thus, I think this position is scientifically untenable.

- Even if you don’t think that shrimp and fish can suffer, you shouldn’t be that confident in such a judgment. Lots of really smart people think they can. But even if there’s only, say, a 10% chance that fish can suffer, in expectation their suffering still dwarfs all human suffering.

- Even if you think only higher animals like mammals and birds can suffer, there are enough of them that wild animal suffering is still very serious.

So far, I’ve argued that:

- Pain and suffering are bad.

- Nature contains huge amounts of pain and suffering. Probably wild animals experience more suffering in a few weeks than humans have ever experienced.

- Therefore, pain and suffering in nature is very bad.

However, in order to make the case for dealing with wild animal suffering, I’d have to show that wild animal suffering is the sort of thing we can do something about. So, can we?

Well, you as an individual can do something about wild animal suffering by giving your money to the wild animal initiative. At this point, they’re mostly doing research into ways to decrease wild animal suffering. If you think wild animal suffering is really bad but aren’t exactly sure what to do about it, then it makes sense to fund research by people who are trying to figure out what to do about it. Much of their research is pretty important. Probably we should spend at least a bit of time doing research onto the worst thing in the world—something that causes in a few months more suffering than has existed in human history.

Beyond funding research into ways of reducing wild animal suffering, which is the most important short-term goal, I think there are some actions that can be taken to combat wild animal suffering:

- It looks not extremely unlikely that fairly soon advanced AI will develop that will enable us to do something about very advanced problems. An AI superintelligence boom may be in the making. If this is so, then ideally we’ll try to get concern about wild animal suffering talked about, so that when the AIs have this ability, they’ll be likely to take actions to majorly reduce wild animal suffering.

- Doing something about climate change may be a good way to reduce wild animal suffering (though this is subject to lots of uncertainty). Glenn has recently argued that climate change makes nature more hazardous, thus increasing the number of R-strategists. Given that these ecological shifts, wherein more animals live short lives, could last millions of years, preventing climate change might be very important. Similarly, a warmer climate will leave more of the world habitable, which likely will disrupt populations in the short run, but lead to a greater population in the long run—thus bringing about more wild animal suffering.

- We can use gene drives to eliminate particularly painful parasites. This has been suggested by Kevin Esvelt, a leading researcher who was one of the first people to identify that gene drives could be used to eliminate malaria-carrying mosquitos. But similarly, they can be used to eliminate particularly painful parasites that negatively impact wild animals! The new world screwworm is a kind of parasite that lays magots in the flesh of their victims, leading to almost unfathomable amounts of pain when it infects a wound in humans. It’s just as painful for wild animals; we could simply get rid of it by genetic engineering. We’ve eliminated them from North America already; we could do the same for South America.

- Wild animals can be vaccinated against particularly terrible diseases. This is similar to how we’ve reduced mortality in humans.

- Maybe—and this one is more long-term and speculative—we could give animals contraceptives to keep their population in control. Then perhaps we could also, after making populations small, eliminate predation. Again, this is very speculative and would require a ton of research, but a small population of animals with adequate access to food and without predation would make nature paradise rather than hell. These things seem worth at least considering.

We should of course be gradual and cautious in our changes to nature. Changes that are too dramatic and rapid could easily backfire. But this is a reason for caution, not inaction. We’ve already made many drastic changes to nature; there’s no reason that efforts to make nature more humane and compassionate will inevitably backfire or produce worse effects than those we’re already inflicting.

I think, therefore, that actions to combat wild animal suffering are both very valuable and are potentially feasible. Given that there’s so much suffering in nature, even making a bit of progress would be very valuable. If after dying you’d have to live the lives of every creature on earth, you’d be quite supportive of actions designed to combat wild animal suffering. In fact, every other action’s importance would pale in comparison to our actions to combat wild animal suffering—one who lived the life of every living creature would spend millions of times more days as a wild animal than a human.

This means we should take it seriously. If you’d regard a problem as serious if you had to inhabit the lives of its victims, then it must be genuinely serious. If you’d regard it as by far the most serious thing in the world if you inhabited the lives of its victims, then it’s the single most serious thing in the world!

I hope you’ll join me in trying to take on the worst thing in the world which is almost universally ignored, despite its seriousness. I know it sounds weird to care about it, but it’s really, really important! If you in response to this article set up a payment of at least 50 dollars a month to the wild initiative, I’ll give you a free paid subscription.

Mange is spreading in wombats in Australia. I saw a severely debilitated (dying) wombat on my parents farm. WIRES animal rescue couldn't help, so I was left wondering whether to kill it or not. I didn't because I worried about making the suffering worse. Kind of wish I owned a gun in that moment.