Crossposted on my blog.

Imagine you were walking past a drowning child. The child kicks, screams, and cries, as they drown, and are about to be resigned to a watery grave, when you walk by. You can save them if you jump into the pool and pull them out. But doing so would come at a cost. You’re currently wearing a very expensive suit—about 5,000 dollars—or perhaps your suit is cheap but has a 5,000 dollar bill in your pocket that would be ruined if you save the child (it’s a very deep pocket—you can’t pull it out in time). Clearly, in such a case, even though it would cost significant money, you’d be obligated to jump into the pond to save the child.

Long before I was born, Peter Singer argued that this case shows that we have an oblgliation to donate to effective charities. The best charities—which you can, at any time, donate to—save lives for a few thousand dollars each. Just as you’re obligated to sacrifice a few thousand dollars to pull the child out of the pond and save them, you’re obligated to sacrifice a few thousand dollars to save a far-away child who would otherwise die of malaria.

In Singer’s original formulation, he used the drowning child case to support the following principle: if you can prevent something very bad from happening without sacrificing anything of comparable moral value, you should do so. For example, if you can prevent a woman from being raped or a person from being murdered at the cost of 700 dollars, you should do so, because averting rape and murder is more valuable than 700 dollars. From this, he deduces that you should give your discretionary spending to effective charities. You shouldn’t spend 5,000 dollars going to Hawaii when you could instead save a person’s life.

But I think we can make a much more direct argument: failure to give to effective charities is morally equivalent to walking past drowning children. Therefore, you have an obligation to give to effective charities, just as you would have an obligation to pull drowning children out of ponds (it seems this is how everyone has, in the intervening years, interpreted Singer’s argument, even though it’s not what was originally intended).

In both the case where you pull the child out of a pond and the case where you donate to effective charities, you can avert a death at the cost of just a few thousand dollars. This seems to be the salient feature of the situation—the reason to wade in and save the child seems to be that you can save a life at small cost. The alternative is to come up with some gerrymandered explanation of why you should save the child from the pond but not from malaria, but that’s less plausible than the simple account that you should prevent terrible things from happening if you can do so at comparatively minor cost.

Still, lots of people argue that there are important differences between pulling kids from ponds and donating to, say, the Against Malaria Foundation. Let’s address them.

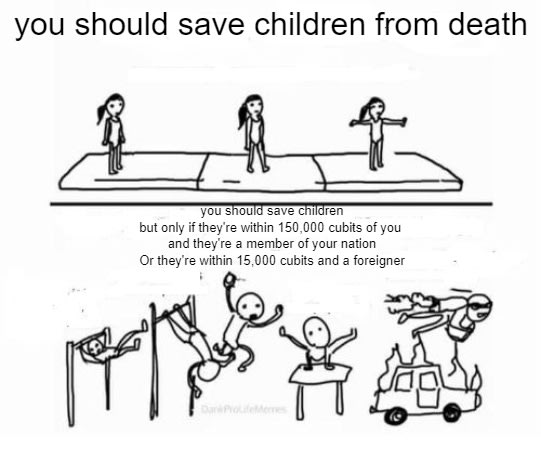

The most common claim is that there’s a difference in terms of proximity. You are only obligated to save the child because they’re near you—if they were far away, you wouldn’t be obligated to save them. This account suffers from two problems: it’s false in a first way, and it’s false in a second way.

First of all, the idea that you’re only obligated to save people who are near you is crazy. Imagine that you could wade into the pond to press a button that would save a child from drowning who was far away. Clearly, you should still do that. But in that case, there’s as much lack of proximity as there is when you donate to effective charities.

Second of all, proximity—at least in the sense of someone being physically close to you in space—is obviously not morally important. Suppose that a child is drowning in a plane and it costs money to press a button that would save them from drowning. Would your reason to save them decrease as they recede into the distance—as they get farther away? Is your obligation to save aliens within one galaxy of you much stronger than your reason to save aliens within two galaxies of you? No, that’s crazy! It doesn’t get less important to save people simply because they’ve taken planes far away.

When claiming that proximity refutes the drowning child argument, lots of people like to say is that you have a great obligation to your friends and family. I don’t know what prompts them to say this in response to the drowning child argument, as it has nothing to do with the argument! Even if you have special obligations to your friends and family, your reasons to save drowning children that you don’t know are still equal to your reasons to save kids you don’t know who might get malaria. The drowning child is not your child—they’re a child that you don’t know personally.

People often claim that you have a greater obligation to those in your own country than to foreigners. I’m doubtful of this, but let’s grant it. Now imagine that you’re on the Mexican border and see a drowning child. They’re not a member of your country. Nevertheless, you should wade in the pond and save them, even at the cost of an expensive suit. Failing to give to effective charities, I claim, is like ignoring the drowning Mexican child—even though they’re not part of your country, you still have an obligation to save them.

Additionally, it’s often claimed that there’s an important difference in that in the drowning child scenario, you’re the only person who can save them, while when giving to charity, others can save them to. I’ve always found this idea super weird: your reason to save people doesn’t evaporate just because other people aren’t following their duty to save people. We can see this by imagining in the drowning children that there are a bunch of nearby assholes ignoring the child as he drowns. Does that eliminate your reason to save the child? No, obviously not. But this case is, in terms of other people not acting to save the child, analogous real world charitable donations.

The final consideration—and this one is the only that bears any weight—is that there are many drowning children. Imagine that there wasn’t just one drowning child, but hundreds of thousands—you could never save them all. It’s plausible that you wouldn’t be obligated to spend your entire life saving children, never enjoying things.

The main thing to note about this is that even if it’s right, maybe it means we’re not all required to spend all of our time saving children, but it still means we’re required to do a lot. A person who never saved even a single drowning child, who ignored the cries of every child who drowned, would be monstrous. So while perhaps you don’t have to give all your money to effective charities, accepting this reasoning would still mean you have an obligation to make charitable giving a main part of your life—say by giving a significant share of your income to effective charities.

I’m also dubious that this justifies spending money on luxuries. In a world where kids were constantly drowning, it doesn’t seem justified to, say, spend thousands of dollars on vacation when you could instead save a child. A child’s life is just so much more important than a trip to Europe. Your reason to save a child doesn’t depend on how many previous children you’ve saved—or so it seems. If I can’t remember whether I lost 10,000 dollars yesterday saving drowning children or gambling, it doesn’t seem I need to figure out which of these I did to decide whether I should save a drowning child. But if we accept this principle, that whether you previously spent your money on saving children or doing other stuff doesn’t affect whether you should currently spend your money on saving children, then your reason to save children is the same as it would be if you hadn’t saved any children. But clearly, if you were choosing between saving a child from a pond and going on vacation, and you hadn’t saved any children, you’d be obligated to save the child. It follows then that you have an obligation to save a child if the alternative is going on vacation.

This argument has, since I’ve heard it, struck me as obviously, irrefutably correct. We certainly have an obligation to make saving children—when we can save hundreds at comparatively minor cost—a significant life project. If a person can save a life a year, without majorly jeopardizing their welfare, just by tithing to effective charities, failing to do so seems clearly immoral.

If you’re convinced by this, I’d encourage you to take a Giving What We Can pledge (if you do this in response to this article, I’ll provide a free paid subscription) or give to GiveWell charities. Most people are, inadvertently, doing things as bad as walking past drowning children. We have significant reason to stop doing this.

I agree fully with the sentiment, but IMHO as a logical argument it fails, as so many arguments do, not in the details but in making a flawed assumption at the start.

You write: "Clearly, in such a case, even though it would cost significant money, you’d be obligated to jump into the pond to save the child."

But this is simply not true.

For two reasons:

The scenario you describe isn't realistic. None of us wear $5000 suits. For someone who wears a $5000 suit, you're probably right. But for most of us, our mental picture of "I don't want to ruin my clothes" does not translate to "I am not willing to give up $5000." I'm not sure what the equivalent realistic scenario is. But in real cases of people drowning, choking or needing to be resuscitated, many people struggle even to overcome their own timidity to act in public. We see people stabbed and murdered in public places and bystanders not intervening. I do not see compelling evidence that most strangers feel morally compelled to make major personal risks or sacrifices to save a stranger's life. To give a very tangible example, how many people feel obligated to donate a kidney while they're alive to save the life of a stranger? It is something that many of us could do, but almost nobody does. I know that is probably worth more than $5000, but it's closer in order-of-magnitude than ruining our clothes.

Absolutely, it would be a better world for all of us if people did feel obliged to help strangers to the tune of $5000, but we don't live in that world ... yet.

The drowning child analogy is a great way to help people to understand why they should donate to charities like AMF, why they should take the pledge.

But if you present it as a rigorous proof, then it must meet the standards of rigorous proof in order to convince people to change their minds.

Additionally, my sense is that presenting it as an obligation rather than a free, generous act is not helpful. You risk taking the pleasure and satisfaction out of it for many people, and replacing that with guilt. This might convince some people, but might just cause others to resist and become defensive. There is so much evidence of this, where there are immensely compelling reasons to do things that even cost us nothing (e.g. vote against Trump) and still they do not change most people's behaviour. I think we humans have developed very thick skins and do not get forced into doing things by logical reasoning if we don't want to be.

Your argument seems to be roughly an appeal to the intuition that moral principles should be simple - consistent across space and time, without weird edge cases, not specific to the circumstances of the event. But why should they be?

Imo this is the mistake that people make when they haven't internalized reductionism and naturalism. In other words they are moral realist or otherwise confused. When you realize that "morality" is just "preferences" with a bunch of pointless religious, mystical and philosophical baggage, the situation becomes clearer.

Because preferences are properties of human brains, not physical laws there is no particular reason to expect them to have low Kolmogorov complexity. And to say that you "should" actually be consistent about moral principles is an empty assertion that entirely rests on a hazy and unnatural definition of "should".

I do think this is correct to an extent, but also that much moral progress has been made by reflecting on our moral inconsistencies, and smoothing them out. I at least value fairness, which is a complicated concept, but also is actively repulsed by the idea that those closer to me should weigh more in society's moral calculations. Other values I have, like family, convenience, selfish hedonism, friendship, etc are at odds with this fairness value in many circumstances.

But I think its still useful to connect the drowning child argument with the parts of me which resonate with it, and think about actually how much I care about those parts of me over other parts in such circumstances.

Human morality is complicated, and I would prefer more people 'round these parts do moral reflection by doing & feeling rather than thinking, but I don't think there's no place for argument in moral reflection.

I think there's plenty of place for argument in moral reflection, but part of that argument includes accepting that things aren't necessarily "obvious" or "irrefutable" because they're intuitively appealing. Personally I think the drowning child experiment is pretty useful as thought experiments go, but human morality in practice is so complicated that even Peter Singer doesn't act consistently with it, and I don't think it's because he doesn't care.

I am not receptive to browbeating. I suspect most people in the world are not, either. I don't know what you intend to accomplish by telling people that every single one of their valued life choices is morally equivalent to letting a child die.

If your answer is "I think people will be receptive to this", I have completely different intuitions. If your answer is "I want to highlight true and important arguments even if nobody is receptive to them", you're welcome to do that, but that has basically no impact on the audience of this forum.

The drowning child motivated a lot of people to be more thoughtful about helping people far away from them. But the EA project has evolved much further beyond that. We have institutions to manage, careers to create, money to spend, regulatory agendas to advance, causes to explore. I think it's time to retire the drowning child, and send it the way of the paperclip maximizer.

I'm not clear on whether you think the drowning child argument is browbeating by nature, or whether you think that just this particular presentation of it is browbeating. (Your remark about retiring the drowning child implies the former, but another of your comments elsewhere implies that you can use the drowning child argument without browbeating people with it?)

Anyway, I don't think it's time to retire the argument, I still feel like I hear a lot of people cite it as insightful for them.

Maybe it was an exaggeration to say it should be retired. It was an important source of insight for me as well. But I think it is used in a browbeating way very often, and this post is a strong example of that. I think the drowning child argument is best used as a way to provoke people to introspect about the inconsistency in their values, not to tell them how immoral all of their actions are.

Even if most aren't receptive to the argument, the argument may still be correct. In which case its still valuable to argue for and write about.

For me it was interesting what others wrote, because we have very different approaches to it. And personally I feel, it's good to rethink such terms and dogmata from time to time , even you already have.

Often we need to discuss them often until a new understanding or even a way of thinking about things takes over.

I'm kinda new to EA and this forum, maybe for some of you others it's maybe kind of boring, when one has had these thoughts or discussions already years ago, of course they are.

But I feel it's a very divers community in many ways like are, schooling, social enviroment. So its maybe useful to get everyone to a point where more elabourate discussions and thoughts can go on....

In short, never underestimate getting the basics straight...over and over again for new arrivals.

My understanding of this (blog) post is a restating of the drowning child thought experiment in OP's voice, with their confident personal writing style. I'm not certain about their intentions behind the article.

In terms using the drowning child argument in general, particularly when explaining what is EA to people who have never heard it before, I do still think it's useful; people understand the general meaning behind it even when only half-explained in 45 seconds by non-philsophers.

That's fair, if it's more of an expository exercise for OP's own sake, I can respect that. But

is exactly why I'm not a fan of using it to browbeat people. It is simple and makes its point clear without you needing to tell people how immoral they are.

The strongest counterargument for the Drowning Child argument is "reciprocity".

If a person saves a nearby drowning child, there is a probability that the saved child then goes onto provide positive utility for the rescuer or their family/tribe/nation. A child who is greatly geographically distant, or is unwilling to provide positive utility to others, is less likely to provide positive utility for the rescuer or their family/tribe/nation. This is an evolutionary explanation of why people are more inclined to save children who are nearby, however the argument also applies to ethical egoists.

This argument is understandably unpopular because it's inconsistent with core principles of EA.

But the principle of reciprocity (and adjacent kin selection arguments) absolutely is the most plausible argument for why the human species evolved to behave in an apparently altruistic[1] manner and value it in others in the first place, long before we started on abstract value systems like utilitarianism, and in many cases people still value or practice some behaviours that appear altruistic despite indifference to or active disavowal of utilitarian or deontological arguments for improving others' welfare.

there's an entire literature on "reciprocal altruism"

I don't know if you're even implying this, but the causal mechanism for altruism arising in humans doesn't need to hold any moral force over us. Just because kin selection caused us to be altruistic, doesn't mean we need to think "what would kin selection want?" when deciding how to be altruistic in future. We can replace the causal origin with our own moral foundations, and follow those instead.

For the record, I agree that evolutionary mechanisms need not hold any moral force over us, and lean personally towards considering acts to save human lives of being approximately equal value irrespective of distance and whether anyone actually notices or not. But I still think it's a fairly strong counterargument to point out that the vast majority of humanity does attach moral weight to proximity and community links, as do the institutions they design to do good, and for reasons.

Agreed.

However, remember that unpopularity doesn't mean untrue. We are effective altruists because we succeed at altruism despite the evolutionary and social pressures encouraging us to fail.

Well, I see a very big flaw throughout this explanation and the possibilities one seemingly has.

First of all there is no defining the parameters. The death of a child has no fixed value.

We could find a number for that in many different ways fE even in money like an insurance would do. Even IF we try to do that in "terms of morals" it simply hasn't the same worth for every human.

We could maybe define kind of a minimum value but wouldn't that be a strange discussion? And what about people who doesn't pull the child out inspite of that? Is this no longer a decend human being? Under any circumstances?

(I think, this is kind of the crucial part in the original argument. For me it doesn't work out, in our reality everyone has to find that number (value of a living child) for themselves, so you simply can't deduct any obligations but your own.

Second thing I would suggest is a distinction between giving a share of your belongings/ sacrificing a certain amount of what you have and drowining children knowingly for adding up value/making money.

Not buying one products because of slave labour doesnt automatically mean not getting the product at all, but making a concious decision about the buying per se.

It's very different thing making a concious decision of talking an action you absolutely know the consequences will harm others while you earn with through it.

(In any case its not easy for me seeing the imperative obligation that's allegedly inherent...but lets ignore that for a moment)

This thought would lead us to an obligation thats more effektive and also maybe more practically useful and (and that's important) it shifts "the blame" or shows responsibilities in a more acurate way.

Because, honestly? It seems we have to make people/companies stopp throwing children overboard for profit not making one another miserable for not doing everything in our power not saving them. That's just draining power out of people that are willing to sacrifice something for a greater good/ benefits for not only themselves but others in one very inefficiant way...that's drying it up.

Just what comes up in my mind as I read the original Posting...

Firstly: all hypotheticals such as this can be valuable as philosophical thought experiments but not to make moral value judgements on broad populations. Frankly this is a flawed argument at several levels because there are always consequences to actions and we must consider aggregate impact of action and consequence.

Obviously I think we're all in favor of doing what good we find to be reasonable, however, you may as well take the hypothetical a step or two further: suppose you now have to sacrifice your entire life savings while also risking some probability of loosing your own life in the process of saving that child. Now let's assume that you're a single parent and have several children of your own to care for which may face starvation if you die.

My point is not to be some argumentative pedant. My point is that these moral hypotheticals are rarely black and white. There is always nuance to be considered.

I address that in the article.

Executive summary: The drowning child argument demonstrates that we have a moral obligation to donate significantly to effective charities, as failing to do so is equivalent to ignoring a drowning child we could easily save.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.