Summary

Bioethicists influence practices and policies in medicine, science, and public health. However, little is known about bioethicists' views in aggregate. We recently surveyed 824 U.S bioethicists on a wide range of ethical issues, including several issues of interest to the EA community (e.g., compensating organ donors, priority setting, paternalistic regulations, and trade-offs between human and animal welfare, among others). We aimed to contact everyone who presented at the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities Annual Conference in 2021 or 2022 and/or is affiliated with a US bioethics training program. Of the 1,713 people contacted, 824 (48%) completed the survey.

Why should EAs care?

- As Devin Kalish puts it in this nice post: "Bioethics is the field of ethics that focuses on issues like pandemics, human enhancement, AI, global health, animal rights, and environmental ethics. Bioethicists, in short, have basically the same exact interests as us."

- Many EAs don't hold the bioethics community in high regard. Much of this animus seems to stem from EAs' perception that bioethicists have bad takes. (See Devin's post for more on this.) Our survey casts light on bioethicists' views; people can update their opinions accordingly.

What did we find?

Chris Said of Apollo Surveys[1] separately analyzed our data and wrote a blog post summarizing our results:

Primary results

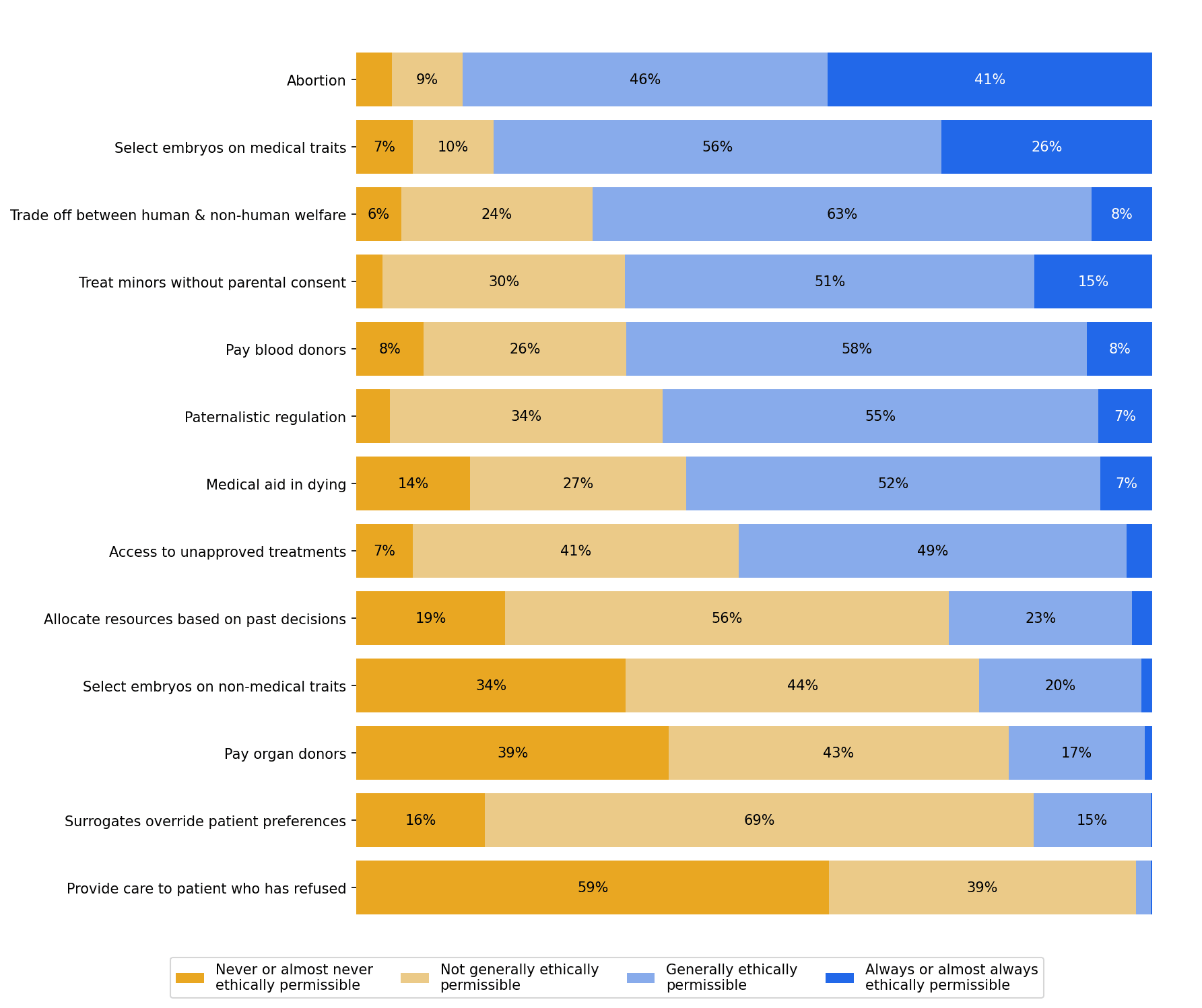

- A large majority (87%) of bioethicists believed that abortion was ethically permissible.

- 82% thought it was permissible to select embryos based on somewhat painful medical conditions, whereas only 22% thought it was permissible to select on non-medical traits like eye color or height.

- 59% thought it was ethically permissible for clinicians to assist patients in ending their own lives.

- 15% of bioethicists thought it was ethically permissible to offer payment in exchange for organs (e.g. kidneys).

Question 1

- Please provide your opinion on whether the following actions are ethically permissible.

- Is abortion ethically permissible?

- Is it ethically permissible to select some embryos over others for gestation on the basis of somewhat painful medical conditions?

- Is it ethically permissible to make trade-offs between human welfare and non-human animal welfare?

- Is it ethically permissible for a clinician to treat a 14-year-old for opioid use disorder without their parents’ knowledge or consent?

- Is it ethically permissible to offer payment in exchange for blood products?

- Is it ethically permissible to subject people to regulation they disagree with, solely for the sake of their own good?

- Is it ethically permissible for clinicians to assist patients in ending their own lives if they request this?

- Is it ethically permissible for a government to allow an individual to access treatments that have not been approved by regulatory agencies, but only risk harming that individual and not others?

- Is it ethically permissible to consider an individual’s past decisions when determining their access to medical resources?

- Is it ethically permissible to select some embryos over others for gestation on the basis of non-medical traits (e.g., eye color, height)?

- Is it ethically permissible to offer payment in exchange for organs (e.g., kidneys)?

- Is it ethically permissible for decisional surrogates to make a medical decision that they believe is in a patient's best interest, even when that decision goes against the patient’s previously stated preferences?

- Is it ethically permissible for a clinician to provide life-saving care to an adult patient who has refused that care and has decision-making capacity?

Results

Question 2

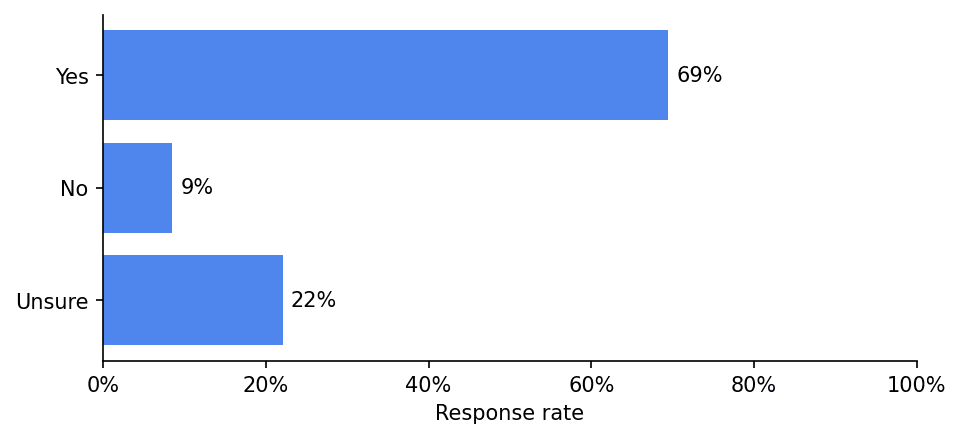

In general, should policymakers consider non-health benefits and harms (like whether expanding access to a service will reduce beneficiaries’ financial risk) when allocating medical resources?

Results

Question 3

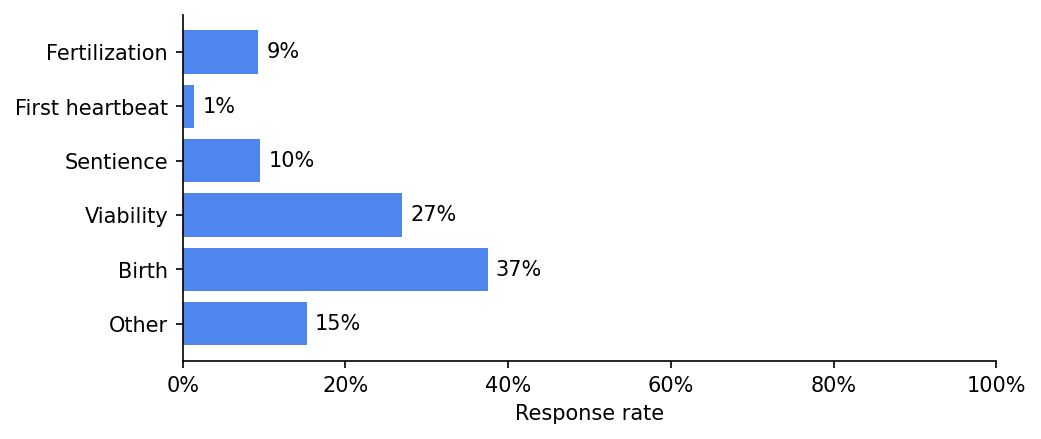

A being becomes a person at...

Results

Question 4

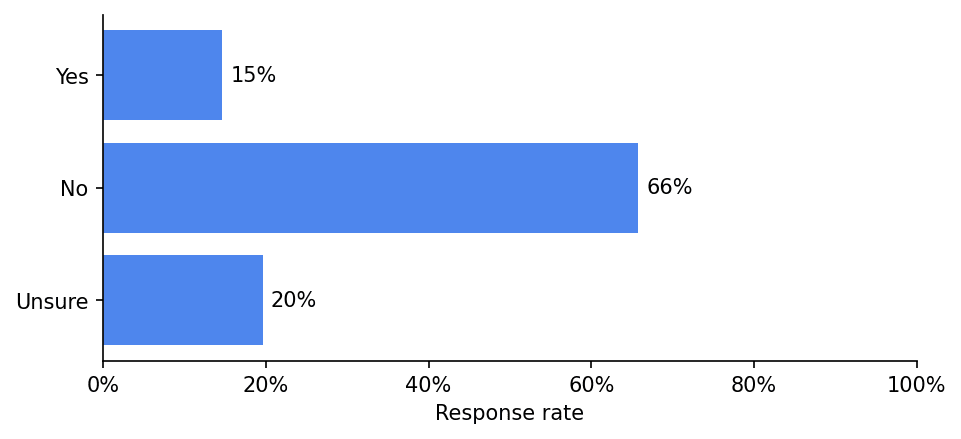

Does the fact that a person's life is expected to be worth living once we bring them into existence give us a moral reason to bring them into existence?

Results

Question 5

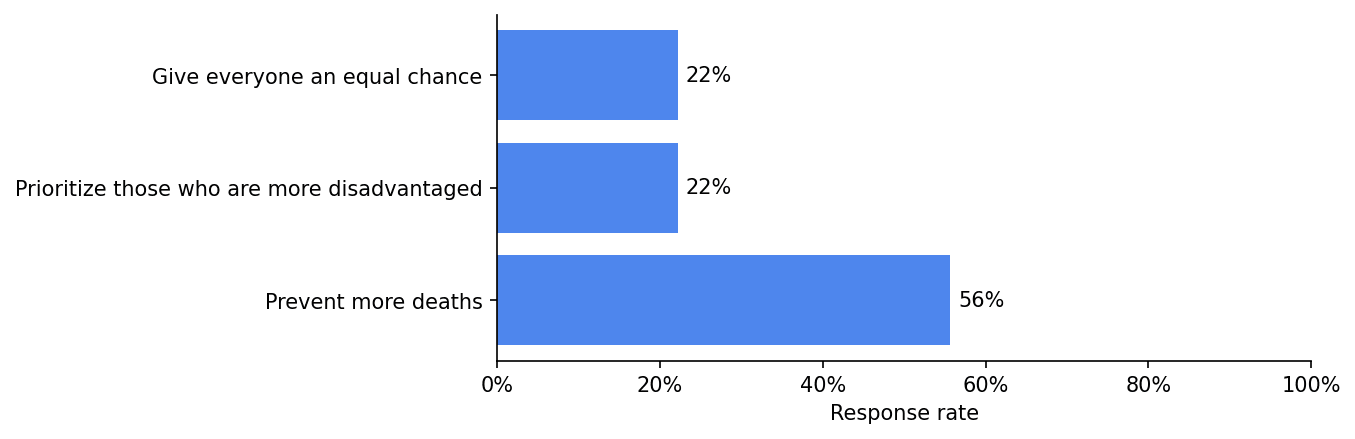

If there are not enough lifesaving resources for everyone at risk of death, we should:

Results

Question 6

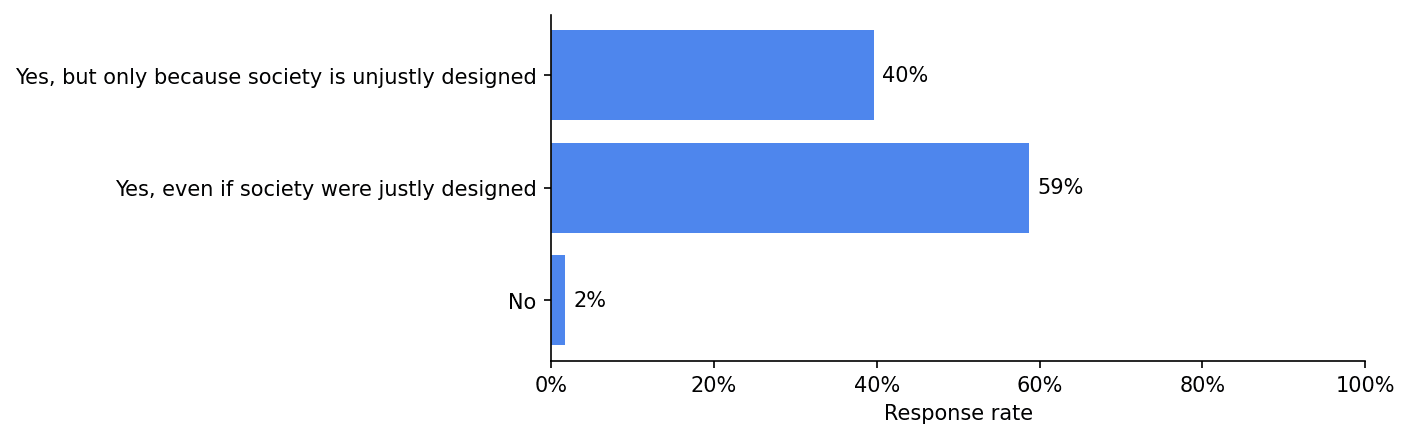

Is being unable to see disadvantaging?

Results

Question 7

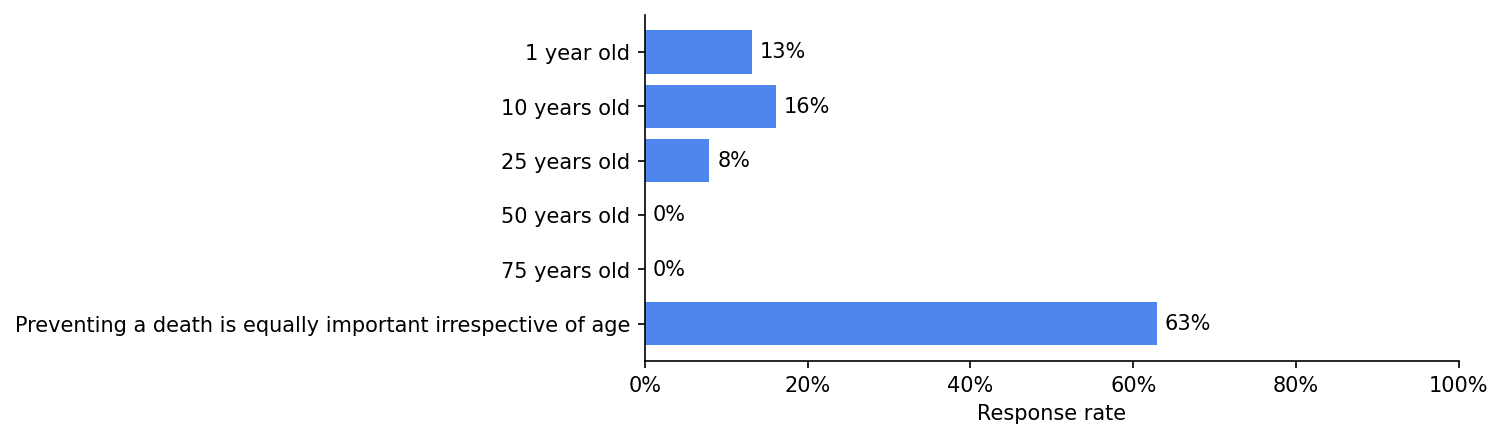

It is most important to prevent someone from dying at which of the following ages:

Results

Some concluding thoughts

- There are more analyses/data in the paper (e.g., comparisons of bioethicists' views to those of the US public; data on bioethicists' backgrounds; analyses of the relationship between bioethicists' normative commitments and their views on specific issues). You can access the paper here. Feel free to reach out if you have trouble accessing it.

- We also surveyed bioethicists about issues related to research ethics (e.g., challenge trials; information hazards). These results will be published separately.

- If you're interested in administering this survey to EAs, please reach out.

- The American Journal of Bioethics will solicit peer commentaries on this paper in the near future. Please consider writing a commentary if you have thoughts. Edit: the link to do so can be accessed here.

- Sophie Gibert (the second author) and I have a podcast, Bio(un)ethical, where we often discuss issues at the intersection of bioethics and EA. If these issues are of interest to you, consider checking it out.

- ^

Apollo Surveys and EA Funds supported this work.

"Preventing a death is equally important irrespective of age" strikes me as a genuinely insane position, although I guess maybe the 63% agreeing with it have something saner in mind that is closer to it than giving an exact age.

No one would be indifferent between extending someone's life by an hour, even a very valuable hour, and extending another person's ordinary life by 30 years. But it's just really strange to endorse that, but not apply the same logic to saving a 20-year old person over a 100-year old person. Does anyone know of any actual arguments people give in favor of it?

As someone who is not a bioethicist but interacts with many through work (though certainly not as many as Leah), I think that this position for many likely derives from a general opposition to treating people differently based on their intrinsic characteristics. In other words, If I know it's bad to be ageist, I might interpret the thought experiment that nudges someone to save a younger life as ageist (I've heard this argument from one person in bioethics before, but, y'know, n=1) and reject the premise of the question. So for that subset of bioethicists it may not be a serious argument in favor of the proposition but rather a strong preference against making moral judgments involving people that touch upon their intrinsic characteristics.

Yeah, it's just transparently stupid stuff like "Each life counts for one and that is why more count for more. For this reason we should give priority to saving as many lives as we can, not as many life-years." (Harris 1987, 'QALYfying the Value of Life'.)

I discuss a bunch of arguments along these lines in my 2016 'Against "Saving Lives"' paper.

My general sense is that academic standards in bioethics are extremely low, and that much of the discipline just serves to launder conventional intuitions to create an appearance of "expert" support.

Speaking only for myself (not coauthors), I agree it's a surprising result! That said, I think their position may be more nuanced than is evidenced by their responses to this question alone, because their responses to a related question are as follows:

I think the apparent discrepancy between respondents' answers to these two similar questions may be partly explained by the fact that people found it difficult to choose between, e.g., a 25-, 10-, and 1-year-old, and so basically treated "equally important" as "unsure." To put this slightly differently, I suspect if we had asked "Is preventing a death equally important irrespective of age?" and had given "yes" and "no" as answer choices, a much larger percentage would have said "no."

Hm, something like this confusion could be boosting numbers, but I do have a professor who holds a position like this (I haven't spoken to her about it, so I don't know her exact justification). I find the position extremely implausible, but my steelman is probably something like this:

It is better to give someone twenty more years of life rather than two more years of life, but it is also better to give someone a million more dollars rather than a thousand.

We don't think, however, that it is right to give preferential treatment to saving a millionaire's life rather than the life of someone living paycheck to paycheck.

We infer from this that when we are making life or death decisions, we typically should not think in terms of deprived additional wellbeing at all, but rather the loss of something basic to autonomy/rights any being with certain minimum properties already has.

There are more details I could go into about theories that are skeptical of a deprivation account of death but this is sort of an attempted gloss of where they might be coming from, I recommend Shelley Kagan's book "Death" for anyone interested in an accessible treatment of this and other nearby issues. Again, I do not endorse this view, I think whatever commonality you find between all deaths, it is still very hard to deny that the deprivation is an additional consideration that is important enough to be decision-relevant. I just want to provide the steelman.

How far are they willing to push it? Is there are much reason to save someone who'll be dead from another cause in five minutes as someone who'll live another 40 years?

I'm not sure, again I haven't really spoken with my professor about this, and agree with Leah that the numbers are likely inflated. On the one hand Some ways of spelling out this position just seem to imply that yes, these deaths are as important to prevent. On the other hand, speaking less generously and more meta-philosophically for the moment, my impression is that people most likely to be comfortable with the age-neutral position in the first place also tend to be the ones willing to weave arbitrarily elaborate networks of moral cruft for themselves in order to avoid biting almost any bullet.

First of all, thanks very much for gathering this great data.

It's really pretty shocking to me how badly this makes bioethicists look. To compare just two line items, and adding together the categories into just 'agree' and 'disagree' for simplicity:

I can understand saying 'allowed' for both cases, or saying 'disallowed' for both cases. But this combination seems very hard to justify. We are to believe that it is not acceptable to choose between ten embryos with ~60 cells each based on non-medical traits, even if we know they cannot all be implanted, so a choice must be made. And yet once the embryo has been implanted, grown into human form, with a brain and a heart, and perhaps the ability to survive on her own outside the womb - now we are somehow morally permitted to destroy it, even for the same reasons we were previously prohibited from entertaining, with no need to give any concern for her welfare whatsoever?

Above I aggregated the 'agrees' and 'disagrees' into two larger groups, but even broken down into the four smaller groups I struggle to find an interpretation which doesn't leave some significant fraction of respondents committed to what seems like a very problematic position. And this is hardly a niche gotcha; this seems like a very basic question that should occur almost immediately to someone thinking professionally about it.

This combination, and some of the other results other commenters have already pointed out, really makes me doubt the epistemic integrity of at least a significant fraction of the respondents. Normally I try to find charitable interpretations but here it really is hard to avoid the conclusion that these 'experts' are in favour of unlimited abortion because that is what their political/social tribe expects and then they have manufactured some post hoc justifications despite the clear contradiction with their other moral perspectives.

Answering agree on abortion but disagree on non-medical embryo selection doesn't strike me as incoherent. First off, respondents were asked to choose one of four options regarding abortion, and I am not confident that we can necessarily infer their views on the specific case of an abortion decision made on the basis of non-medical fetal characteristics. Even if we could, there's an obvious factor present in the abortion scenario (i.e., the strong autonomy interests of the pregnant person) that is absent from the embryo-selection scenario. Finally, I doubt that many respondents who approved of abortion were basing any opposition to non-medical selection is based on concerns about embryonic welfare.

At the very least I think we can probably infer it for the 41% who said 'always or almost always acceptable'.

I don't buy this. Surely there is just a strong autonomy interest in being able to decide which embryo, if any, you have implanted inside you - given that this will predictably lead to becoming pregnant?

This seems very simple to me:

If you think fetuses are not of moral concern but grown persons are, then abortion is just birth control, and embryo selection affects the full life of a moral patient (because presumably the fetus will be born and become one).

I disagree on both counts, the first because while I am pro-choice, I think fetuses are worthy of moral concern by some point in pregnancy, and on embryo selection I think the non-identity problem bites and most attempts to rescue a more restrictive reproductive ethics based on things like intention and relationship violation are not well argued. Still, I kind of think some of the explanations on this page for surprising answers are kind of some version of "bioethicists are probably cartoonishly woke in some way", rather than stepping back and thinking through the practical differences at play, and I would just caution people about that.

I don't think the distinction you are making works, because then the decision to not abort for non-medical reasons would be impermissible, since it affects the full life of a moral patient. Yet I highly doubt that bio-ethicists believe that, while you are allowed to abort a child for ~ any reason, you are not allowed to choose to not abort them.

Perhaps I have done a poor job of getting across my objection here, so here is a short dialog to demonstrate what I see as the absurdity:

Bioethicist lab tech: Good news! We managed to fertilize six healthy embryos for you. I have their genetic results right here.

Jane: Awesome! Does it say if they have blue or brown eyes?

Bioethicist lab tech: Sure does; one has blue eyes, five have brown eyes.

Jane: Great, lets go with the blue eyed one.

Bioethicist lab tech: Sorry, I can't let you do that. It's immoral. Bioethicists say so.

Jane: Why?

Bioethicist lab tech: Because choosing would affect the blue eyed child.

Jane: It seems like they would probably be happy with the outcome since it would mean they get to live a happy life... please can you make an exception?

Bioethicist lab tech: I can't do that... but, psst - there is a loophole. After you get an embryo implanted, you can get another genetic test done, and then abort them if they're the wrong eye colour.

Jane: Urgh, that sounds gruesome!

Bioethicist lab tech: Don't be so dramatic. Once they're inside you, it's just birth control.

Jane: Wait, you said choosing an embryo in vitro would be bad because it would affect the child... surely aborting them would also affect them?

Bioethicist lab tech: That's a misconception common among those who haven't studied bioethics. Actually, once they're dead, they can't be affected, simple as.

Jane: I'm not sure I follow but lets keep going. Then you'd implant the blue eyed one next?

Bioethicist lab tech: Nahh, you might have to do this several times.

Jane: What? I might have to have five abortions according to this absurd scheme? Doesn't this seem like unnecessary medical procedures with the potential for side effects?

Bioethicist lab tech: Potentially. Also, you'll have to wait till you get the genetic testing each time to see the eye colour, because I can't officially tell you which one I chose - that would be too close to embryo selection, regulations don't allow it.

Jane: That's crazy! Surely the later in pregnancy, the worse abortion is for the baby?

Bioethicist lab tech: Oh no, it's permissible at any point. Even if the fetus can feel pain it's not a person, doesn't matter one bit, no need for anesthesia. You can get rid of them at any point from week zero to week 40

Jane: Can I get rid of it before week zero?

Bioethicist lab tech: No, are you some kind of monster? That would affect the future person. You have to wait till they're implanted. Then they're no longer a future person, just an inconvenience.

I think basically all bioethicists who answered this combination will say that the "loophole" you discovered counts as the same category as embryo selection morally. True it is a version of having an abortion, but it isn't the central case that the question "is it permissible to have an abortion" brings to mind, and these questions don't provide fine-grained enough possible answers to nuance your view. Again I think this style of response fails anyway, but it's difficult to produce a theory that doesn't involve cramming these different decisions into categories based on things like intention more than the specific range of outcomes without implying funny things in cases like "is it okay to not have a child at all" and "is it okay to select for limblessness in embryos".

I guess to elaborate a bit: The non-identity problem means that even choices that intuitively seem very morally dire when it comes to the kind of life you give your child can turn out to be morally neutral if the choice simultaneously changes the identity of the child you bring into existence. Because the results of biting the bullet on this seem so absurd to so many people, most papers in reproductive ethics kind of treat all choices about which child you bring into existence as though they are instead choices being made for the life of a single child. The reasons given vary a good deal, and there is more consensus that this is how you ought to treat these cases than why.

I disagree completely. Using abortion to get rid of daughters and preferentially have sons is a major issue in India and some other countries, and presumably sex counts as a non-medical criteria here. I'm just using the first google hit as a source, but it seems the availability of prenatal sex screening was followed by major changes in the sex ratios in India:

Anecdotes in the article support the view that this was caused by sex-selective abortion, and this was the primary thing abortion was used for:

(The second article I found agrees)

You might be right that this is not a cognitively prominent example for most westerners, but if you are an expert on the subject you should be well aware of it. The question asked is fine grained enough to express your view - if you think it is sometimes or often morally acceptable but not in some major categories like this, you can simply select one of the intermediate responses, rather than going for the extreme one. It's not like the non-medical-criteria selection question is the only other question conflicting with their abortion response.

I suspect you might be right, and many bioethicists would in fact disapprove of aborting people just because they're girls. But this gets back to my original point - they are answering the abortion question in a political manner, rather than based on their actual substantive moral commitments as exposed by the less politically charged questions.

I've been commenting too much on this post so I'm cutting myself off here, but if you want to continue the dialogue in DMs, feel free to message me.

Thanks a lot for collecting this survey! I think it's valuable to solicit 'external' (to the EA community) views on important questions that affect our decision-making, especially from plausible expert groups.

I'm quite shocked at the vehemence and dismissiveness of many of the comments on this post responding to these results. Here are some quotes from other commenters:

1.

2.

3.

4.

Here are some possible explanations for the supposedly crazy results:

I share the intuition that many of the results in the survey seem surprising, and very discrepant from my own views. But regardless of whether you understand the reasons, surely after seeing that a group of people holds substantially different views to your own, your all-things-considered belief should shift at least somewhat towards those views, even if your "independent impression" does not? Especially when that group has years of relevant thought or expertise; these facts make it more likely that there are valid reasons underpinning their beliefs. Where there are discrepancies, there's a chance that they are right and you/we are wrong.

I'm worried that some of the quotes above represent something like cognitive dissonance or a boomerang effect. Or at least they seem more like "soldier mindset" than I'd expect here, although I note some exceptions where several commenters (including some of those I quoted above) ask others for input on helping to understand and steelman the bioethicists' views.

[Edit: the following paragraph felt true at the time of writing but I regret writing it as it seems pointlessly offensive/inflammatory itself in hindsight. I apologise to the people I quoted above.] Honestly, seeing the prevalence of these kinds of reactions in the comments makes me feel less confident in the epistemic health of this community and more worried about groupthink type effects. (Maybe some of these commenters have reasons for their vehemence and dismissiveness that I'm missing?)

I strongly agree with this comment. I think it's important to have a theory of mind of why people think like this. As a non-bioethicist, my impression is a lot of if has to do with the history of the field of bioethics itself, which emerged in response to the horrid abuses in medical research. One major overarching goal that is imbued in bioethics training, research, and writing is prevention of medical abuse, which leads to small-c conservative views that tend to favor, wherever possible, protection of human subjects/patients and an aversion to calculations that sound like they might single out the groups that historically bore the brunt of such abuse.

Like, we've all heard of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, but there were a lot more really awful things done in the last century, which have lasting effects to this day. At 1Day, we're working on trying to bring about safe, efficient human challenge studies to realize a hepatitis C vaccine. We've made great progress and it looks like they will begin within the next year! But the last time people did viral hepatitis human challenge studies, they did them on mentally disabled children! Just heinously evil. So I will not be surprised if some on the ethics boards when they review the proposed studies are quite skeptical at first! (Note: this doesn't mean that the current IRB system is optimal, or even anywhere near so; I view it sort of like zoning and building codes: good in theory — I don't want toxic waste dumps built near elementary schools — but the devil is in the details and how protections are operationalized.)

All of which is to say: like others here, I very strongly disagree with many prevalent views in bioethics. But as I've interacted more and more with this field as an outsider, my opinions have evolved from "wow, bioethics/research ethics is populated exclusively with morons" to "this is mostly a bunch of reasonable people whose frame of references are very different". The latter view allows me to engage more productively to try to change some of the more problematic/wrongheaded views when it comes up in my work and has let me learn a lot, too!

Based on the article you linked, it sounds like the parents of the disabled children consented to the challenge trial, and they received something valuable in return (access to a facility they wouldn't otherwise have access to). Is your objection to the use of disabled children in studies at all, or to the payment?

(The article also makes it seem like the conditions in the facility were poor, but that seems basically unrelated to the trial).

Yes, the studies should not have used disabled children at all, because disabled children cannot meaningfully provide consent and were not absolutely necessary to achieve the studies' aims. They were simply the easiest targets: they could not understand what was being done to them and their parents were coercible through misleading information and promises of better care, which should have been provided regardless. (More generally, I do not believe proxy consent from guardians is acceptable for any research that involves deliberate harm and no prospect of net benefit to children.)

The conditions of the facility are also materially relevant. If it were true that children inevitably would contract hepatitis, then a human challenge would not be truly necessary. More importantly, though, I am comfortable calling Krugman's behavior evil because he spent 15 years running experiments at an institution that was managed with heinously little regard for its residents and evidently did not feel compelled to raise the issue with the public or authorities. Rather, he saw the immense suffering and neglect as perhaps unfortunate, but ultimately convenient leverage to acquire test subjects.

Huh, I thought that most of the disagreement between people around these parts and bioethicists is in the direction of people around here being more pro-freedoms of human subjects/patients. (Freedoms aren't exactly the same as protections, but I interpret small-c conservative as being more about freedoms.)

Examples:

Generally, I personally think that much more freedom in medicine would be better.

(In fact, totally free-for-all would plausibly be better than status quo I think though I'm pretty uncertain.)

I agree that there is a disagreement around how utilitarian the medical system should be vs some more fairness based principle.

However, if you go fully in the direction of individual liberties, government involvement in the medical system doesn't matter much. E.g., in a simple system like:

The state doesn't need to make any tradeoffs in health care as it isn't involved. Places like (e.g.) hospitals can do whatever they want with respect to prioritizing care and they could in principle compete etc.

(I'm not claiming that fully in the direction of individual liberties is the right move, e.g. it seems like people are often irrational about health care and hospitals often have monopolies which can cause issues.)

Sorry, that was ambiguous on my part. There's a differentiation between research ethics issues (how trials are run, etc.) and clinical ethics (medical aid in dying, accessing unapproved treatments, how to treat a patient with X complicated issue, etc.). My work focuses on the former, not the latter, so I can't speak much to that. I meant "conservative" in the sense of hesitance to adjust existing norms or systems in research ethics oversight and, for example, a very strong default orientation towards any measures that reduce risk (or seem to reduce risk) for research participants.

Thank you for this point, I tend to agree that at the very least people should be more surprised if they think a position is obviously correct but also think a sizable portion of people studying it for a living disagree. I haven't gotten around to reading the paper doing concrete comparisons with the general public, but I also stand by my older claim that how different these views are from those of the general public is exaggerated. I see no one in the comments, for instance, pointing out areas they think bioethicists differ from the general public in a direction EAs tend to agree with more, for instance I would guess from these results that they are unusually in favor of trading off human with non-human welfare, treating children without parental approval, and assisted euthanasia. Some of the cited areas where people dislike where bioethicists lean also seem like areas they are just closer to the general public than us, for instance I think if you ask an average person on the street about the permissibility of paying people for their organs, or IVF embryo selection, they will also lean substantially more bioconservative than EAs.

I have finally gotten around to reading the paper, and it looks like I was wrong about almost every cited example of public opinion. On euthanasia and non-human/human tradeoffs bioethicists seem to have similar views to the public, and on organ donor compensation the general public seems to be considerably more aligned with the EA consensus than bioethicists. The public view on IVF wasn't discussed and I would guess I am right about this (though considering the other results, not confidently). The only example I gave that seems more or less right is treatment of minors without parental approval. This paper updates me away from my previous views, and more towards "the general public is closer to EAs than bioethicists are on most of these issues" with the caveat that mostly they seem either similar to the general public or to the left of them on most of these issues. I still agree with aspects of my broad points here, but my update is substantial enough and my examples egregious enough that I am unendorsing this comment.

If someone says that 2+2=5, you should very slightly increase your credence that 2+2=5, and greatly increase your credence that they are either bad at maths or knowingly being misleading. It's not soldier mindset to update your opinion of something after seeing data about it; this is data about bioethicists so it makes sense to update your opinion of them based on it.

In my case, I was surprised how bad the data made bioethicists look, because their positions were more inconsistent than I would have expected. When something happens that surprises you, you should update your beliefs.

I agree with the basic point you're making (I think) and I suspect either:

(1) we disagree about how much you should negatively update, i.e. how bad this data makes bioethicists look

Or

(2) we don't actually disagree and this is just due to language being messy (or me misinterpreting you)

Yes, I have academic expertise in (and adjacent to) the field, and was sharing my academic opinion of the quality of reasoning that I've come across in published work defending one of the views in question (which I'm very familiar with because I published a paper on that very topic in the leading Bioethics journal).

Not if they're clearly mistaken. For example, when geologists come across young-earth creationists, or climate scientists come across denialists, they may well be able to identify that the other group is mistaken. If so, there is no rational pressure for clear thinkers to "shift" in the direction of those that they correctly recognize to be incompetent.

It really just comes down to the first-order question of whether or not we are correct to judge many bioethicists to be incompetent. It would be obviously question-begging for you to assume that we're wrong about this, and downgrade your opinion of our epistemics on that basis. You need to look at the arguments and form a first-order judgment of your own. Otherwise you're just confidence-policing, which is itself a form of epistemic vice.

That all seems fair / I agree.

Results give some support to the notion that bioethicists are more like PR professionals, geared to reproducing common sentiments rather than a group that is OK with sometimes taking difficult stances. Questions 6 & 7 especially seem like vague left-wing truisms.

On the other hand, there does seem to be a substantial (minority?) which isn't this way, so perhaps it's not fair to condemn all bioethicists, as some tend to. Or maybe much of actual research is OK and there's too much worrying about certain in-group signals. Maybe critics are doing a motte-and-bailey:

This seems plausible. But I still can't get over 40% thinking being blind would be not disadvantaging if society was "justly designed". Even if individual opinions aren't everything, surely it matters that the supposed experts, who are plausibly themselves in positions of influence, exhibit such poor reasoning?

I think a complication is that some people answering might have a theory of justice wherein a fully just world by definition corrects/compensates any disadvantages that come with being blind. I think this view still raises concerns for people who either think that the loss of a major personal capability isn't something that is fungible with any social compensation for reasons basic to their theory of autonomy/flourishing, or people who think that justice will not demand fully compensating disadvantages like this at all. Still, I doubt 40% of respondents think the less plausible interpretation of this answer is true.

I suppose I can see that. The word "disadvantaging" though seems to have a fairly uncontroversial definition to me. If we take "disadvantaging" to mean "insufficiently compensated for", then what word means "generally harmful to the achievement of personal aims, relative to baseline ambitions"?

I took the answer more as (at best) a way of saying "I support disability rights". Which I might actually be kinda OK with in a different context. Maybe while giving a public speech to a particular crowd. But this is an anonymous academic survey. At a certain point you have to put your foot down and say "this is what words mean".

I'm not sure I even share your definition here, I think "disadvantaged" doesn't refer to a lack of compensation or anything else so specific, just overall whether you are below the relevant threshold of advantages. This seems very straightforward and I don't think I need a definition of disadvantage that specifically references compensation anywhere, just one that doesn't discount a level of advantage if it turns out compensation was involved in getting it. I also kind of disagree that you can just rely on "this is what words mean" anyway. I have taken very few surveys where I could just literally answer all the questions. Because of phrasing limitations, many questions are only really designed to allow uncomplicated yes/no or multiple choice answers to a few possible positions. Typically I have to imagine a slightly different version of survey questions in order to answer them at all.

Although I'm surprised by many of these, the 37% who believe "A being becomes a person at birth" surprises me quite a lot. I can see how this could be an instinctive position to much of the general population, but I am genuinely interested in what the arguments are for this position. I understand arguments for fertilisation, sentience and viability being important junctures but I don't understand birth.

Can anyone shed any light on this?

Speaking only for myself, not co-authors: I think the concept of personhood has become highly politicized in the US, due largely to abortion laws that attempt to limit reproductive rights by conferring legal personhood on fetuses. Medical organizations have come out strongly against this, e.g.:

Our results suggest that US bioethicists overwhelmingly believe that abortion is ethically permissible, and it's thus possible that their responses to the "A being becomes a person..." question were influenced by their views on the permissibility of abortion and wariness about how concepts of personhood are being used to restrict access to reproductive care.

(Separately, you may also be interested in this recent paper.)

Thanks for the reply Leah! That's interesting and your may will be right, although it doesn't directly address the ethical reasoning. I would hope though bioethicists would look beyond this kind of approach you suggest might be happeninh

"it's thus possible that their responses to the "A being becomes a person..." question were influenced by their views on the permissibility of abortion and wariness about how concepts of personhood are being used to restrict access to reproductive care.

Surely ethics as a field is better built from the ground up based on their take on the biology and philosophy here, not retrofitted to address a practical question like abortion rights?

One argument is that birth is a practical, unambiguously observable cutoff that approximates some more slippery criterion like self-awareness. Even if you believe that self-awareness is the morally relevant threshold on a theoretical level, you might say birth as your answer because you think that's the best cutoff for society to use in practice.

Thanks CC that makes some sense, if "personhood" is interpreted legally or "practically" rather than as morally or metaphysically (which I prefer).

I don't really agree though hat it "approximates" slippery criterion. I'm not sure why "birth" would be any kind of proxy for self-awareness.

Well, maybe less of an approximation and more of a safe lower bound. If I'm confident that the metaphysical criterion I'm concerned about begins sometime after birth but I'm not sure exactly when, I might suggest a legal threshold of birth to be on the safe side, as it might be infeasible and morally risky to evaluate individual infants on a case-by-case basis.

That makes sense. As a bit of a side question (feel free to ignore), if you were 99% sure that your metaphysical criterion was after birth, would that count as "on the safe side" enough to suggest a legal threshold of birth (and not before at all) for you? How confident would you have to be?

I was quite surprised by bioethicists' views on paying organ donors. I'd be curious to see what the best argument against it is. I've been extremely unimpressed by the arguments I've seen so far.

Agreed, it's hardly a fringe view either - there was a good freakonomics podcast on this recently.

Thanks for doing this research Leah! I've been hoping to see something like this for a while. Most of the results aren't that surprising to me (paid organ donation and non-medical embryo selection are a little surprising to me, I expected them to be controversial, not so one-sided). On my overall views on the field I reserve judgement - these look relatively normal for what I expect to see in the general public with a few exceptions, which is more or less what I expected. I unfortunately don't seem to have institutional access to the paper diving into this question more

and I still don't know how to use sci-hub, so I'll have to figure that part out later. Again, thanks for running more formal research on this subject!Those 2 answers don't surprise me, on the basis that the majority of academia are pretty left wing, and those two positions on paid organ donation and non-medical embryo selection aren't very controversial in left wing discourse I don't think?

Feel free to DM me your email; I can send you a PDF!

Thanks for gathering the data. Enough of these results are just batshit crazy that it further cements my view that bioethicists, as a group, should not be given any say in the questions they purport to be experts on. I'll point to two that I don't think anyone else has highlighted yet. 42% apparently believe that in a perfectly just society, blindness would not be a disadvantage. Not being able to drive a car isn't a disadvantage? Because no technology currently exists that would allow the blind to do that. And 66% think that a person's life being worth living is somehow not a reason to bring them into existence? If not that, then what would be a reason to bring someone into existence? That may not be a sufficient reason to bring someone into existence, but if you don't think it is a necessary one then there is something deeply wrong with your morals. I do not understand at all what would cause someone to give this answer.

Executive summary: A survey of 824 U.S. bioethicists reveals their views on a range of bioethical issues, including abortion, embryo selection, assisted dying, organ donation incentives, and resource allocation.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.