Summary

Bioethicists influence practices and policies in medicine, science, and public health. However, little is known about bioethicists' views in aggregate. We recently surveyed 824 U.S bioethicists on a wide range of ethical issues, including several issues of interest to the EA community (e.g., compensating organ donors, priority setting, paternalistic regulations, and trade-offs between human and animal welfare, among others). We aimed to contact everyone who presented at the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities Annual Conference in 2021 or 2022 and/or is affiliated with a US bioethics training program. Of the 1,713 people contacted, 824 (48%) completed the survey.

Why should EAs care?

- As Devin Kalish puts it in this nice post: "Bioethics is the field of ethics that focuses on issues like pandemics, human enhancement, AI, global health, animal rights, and environmental ethics. Bioethicists, in short, have basically the same exact interests as us."

- Many EAs don't hold the bioethics community in high regard. Much of this animus seems to stem from EAs' perception that bioethicists have bad takes. (See Devin's post for more on this.) Our survey casts light on bioethicists' views; people can update their opinions accordingly.

What did we find?

Chris Said of Apollo Surveys[1] separately analyzed our data and wrote a blog post summarizing our results:

Primary results

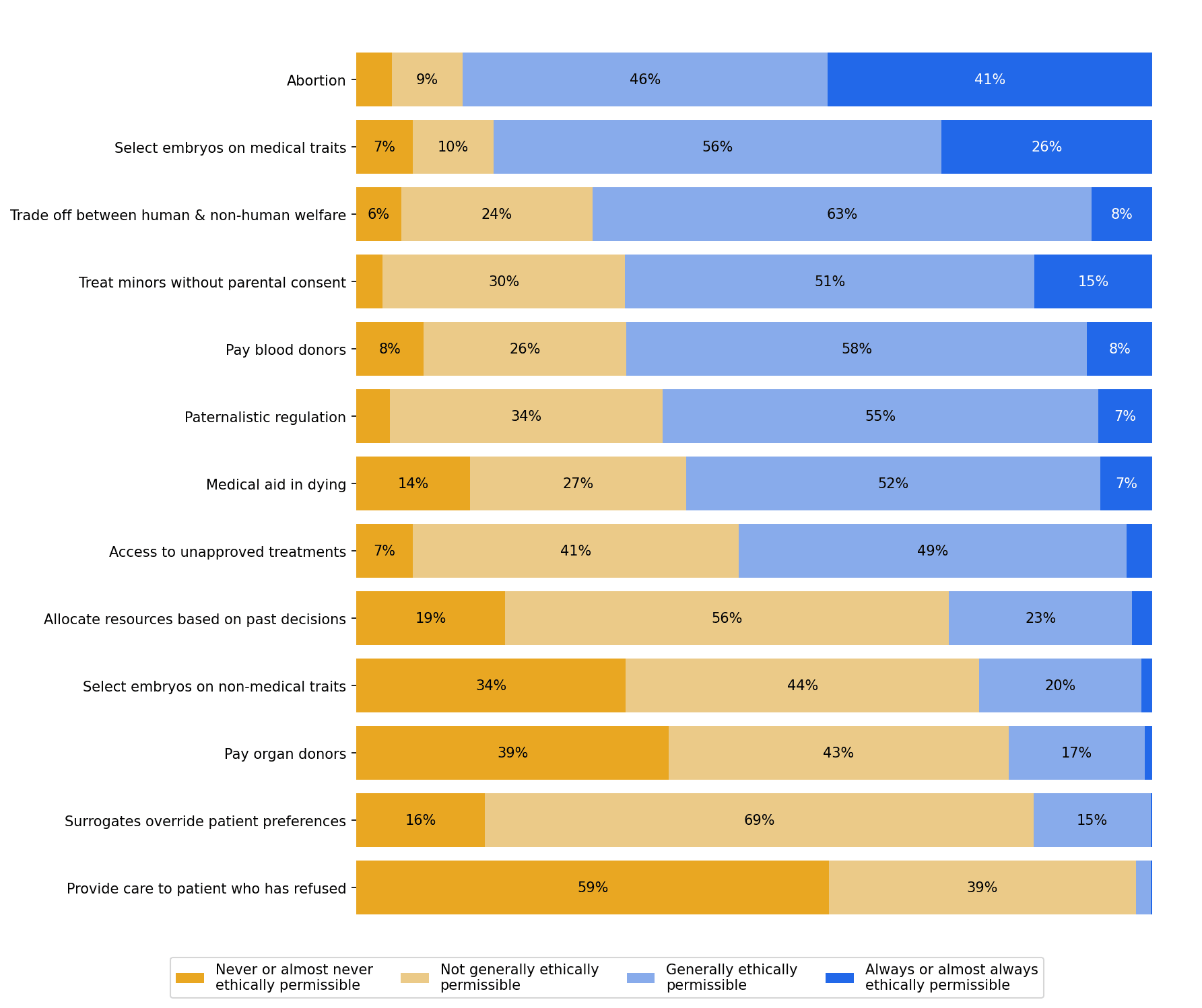

- A large majority (87%) of bioethicists believed that abortion was ethically permissible.

- 82% thought it was permissible to select embryos based on somewhat painful medical conditions, whereas only 22% thought it was permissible to select on non-medical traits like eye color or height.

- 59% thought it was ethically permissible for clinicians to assist patients in ending their own lives.

- 15% of bioethicists thought it was ethically permissible to offer payment in exchange for organs (e.g. kidneys).

Question 1

- Please provide your opinion on whether the following actions are ethically permissible.

- Is abortion ethically permissible?

- Is it ethically permissible to select some embryos over others for gestation on the basis of somewhat painful medical conditions?

- Is it ethically permissible to make trade-offs between human welfare and non-human animal welfare?

- Is it ethically permissible for a clinician to treat a 14-year-old for opioid use disorder without their parents’ knowledge or consent?

- Is it ethically permissible to offer payment in exchange for blood products?

- Is it ethically permissible to subject people to regulation they disagree with, solely for the sake of their own good?

- Is it ethically permissible for clinicians to assist patients in ending their own lives if they request this?

- Is it ethically permissible for a government to allow an individual to access treatments that have not been approved by regulatory agencies, but only risk harming that individual and not others?

- Is it ethically permissible to consider an individual’s past decisions when determining their access to medical resources?

- Is it ethically permissible to select some embryos over others for gestation on the basis of non-medical traits (e.g., eye color, height)?

- Is it ethically permissible to offer payment in exchange for organs (e.g., kidneys)?

- Is it ethically permissible for decisional surrogates to make a medical decision that they believe is in a patient's best interest, even when that decision goes against the patient’s previously stated preferences?

- Is it ethically permissible for a clinician to provide life-saving care to an adult patient who has refused that care and has decision-making capacity?

Results

Question 2

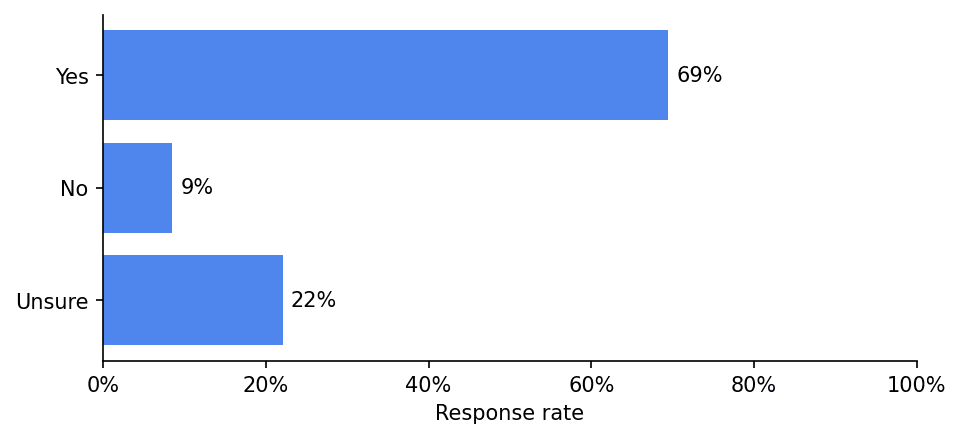

In general, should policymakers consider non-health benefits and harms (like whether expanding access to a service will reduce beneficiaries’ financial risk) when allocating medical resources?

Results

Question 3

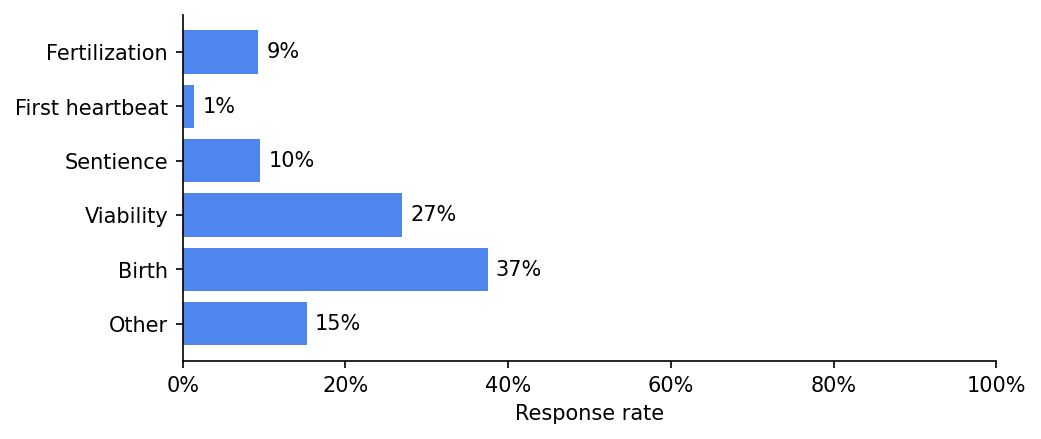

A being becomes a person at...

Results

Question 4

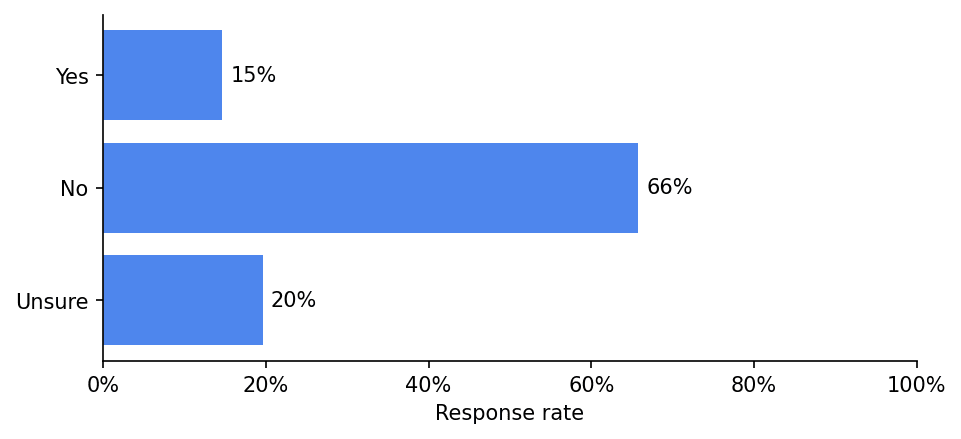

Does the fact that a person's life is expected to be worth living once we bring them into existence give us a moral reason to bring them into existence?

Results

Question 5

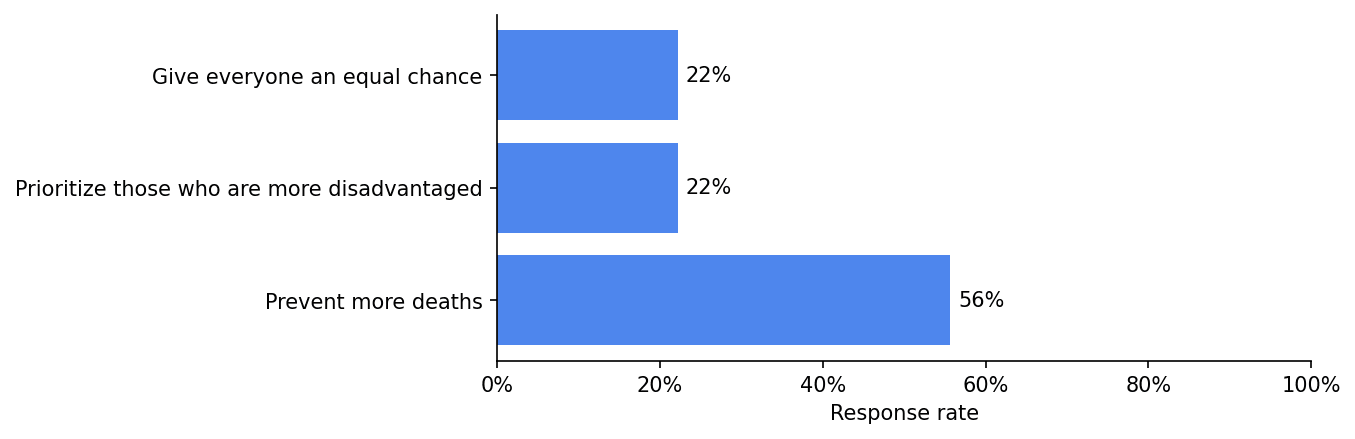

If there are not enough lifesaving resources for everyone at risk of death, we should:

Results

Question 6

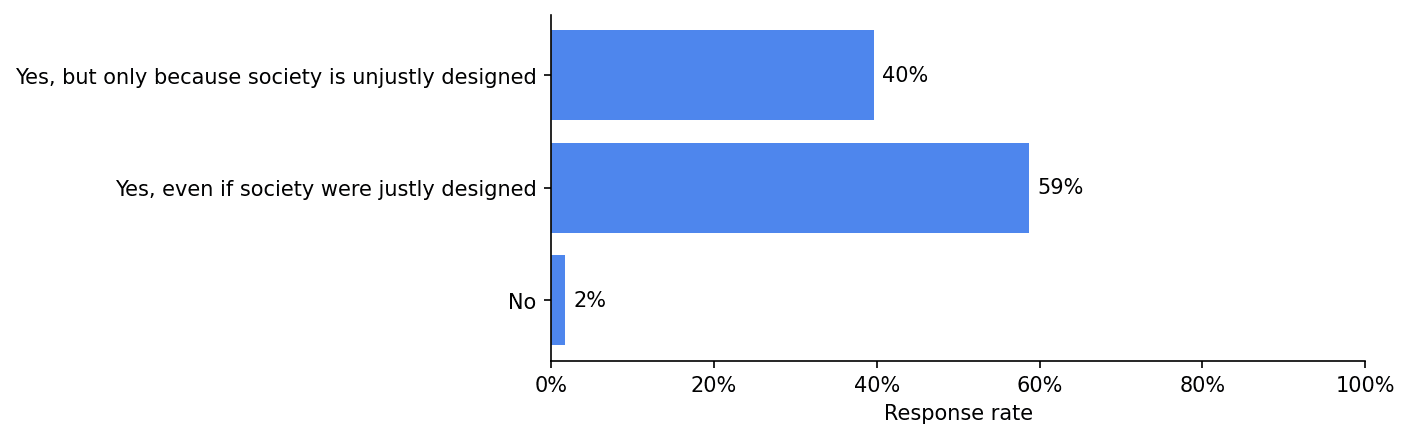

Is being unable to see disadvantaging?

Results

Question 7

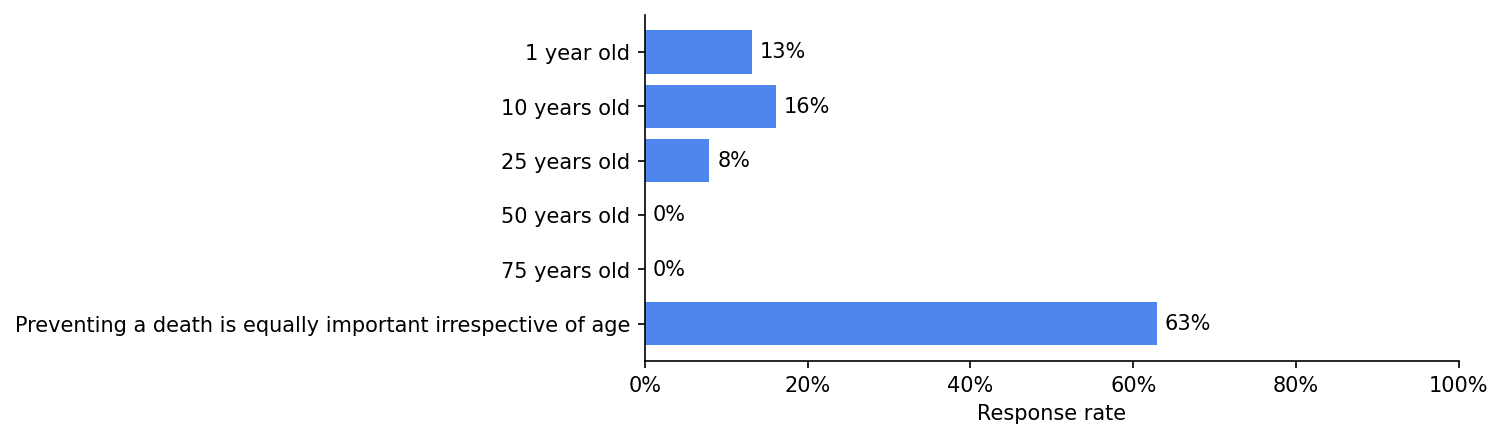

It is most important to prevent someone from dying at which of the following ages:

Results

Some concluding thoughts

- There are more analyses/data in the paper (e.g., comparisons of bioethicists' views to those of the US public; data on bioethicists' backgrounds; analyses of the relationship between bioethicists' normative commitments and their views on specific issues). You can access the paper here. Feel free to reach out if you have trouble accessing it.

- We also surveyed bioethicists about issues related to research ethics (e.g., challenge trials; information hazards). These results will be published separately.

- If you're interested in administering this survey to EAs, please reach out.

- The American Journal of Bioethics will solicit peer commentaries on this paper in the near future. Please consider writing a commentary if you have thoughts. Edit: the link to do so can be accessed here.

- Sophie Gibert (the second author) and I have a podcast, Bio(un)ethical, where we often discuss issues at the intersection of bioethics and EA. If these issues are of interest to you, consider checking it out.

- ^

Apollo Surveys and EA Funds supported this work.

I strongly agree with this comment. I think it's important to have a theory of mind of why people think like this. As a non-bioethicist, my impression is a lot of if has to do with the history of the field of bioethics itself, which emerged in response to the horrid abuses in medical research. One major overarching goal that is imbued in bioethics training, research, and writing is prevention of medical abuse, which leads to small-c conservative views that tend to favor, wherever possible, protection of human subjects/patients and an aversion to calculations that sound like they might single out the groups that historically bore the brunt of such abuse.

Like, we've all heard of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, but there were a lot more really awful things done in the last century, which have lasting effects to this day. At 1Day, we're working on trying to bring about safe, efficient human challenge studies to realize a hepatitis C vaccine. We've made great progress and it looks like they will begin within the next year! But the last time people did viral hepatitis human challenge studies, they did them on mentally disabled children! Just heinously evil. So I will not be surprised if some on the ethics boards when they review the proposed studies are quite skeptical at first! (Note: this doesn't mean that the current IRB system is optimal, or even anywhere near so; I view it sort of like zoning and building codes: good in theory — I don't want toxic waste dumps built near elementary schools — but the devil is in the details and how protections are operationalized.)

All of which is to say: like others here, I very strongly disagree with many prevalent views in bioethics. But as I've interacted more and more with this field as an outsider, my opinions have evolved from "wow, bioethics/research ethics is populated exclusively with morons" to "this is mostly a bunch of reasonable people whose frame of references are very different". The latter view allows me to engage more productively to try to change some of the more problematic/wrongheaded views when it comes up in my work and has let me learn a lot, too!