Epistemic Status: While I feel fairly confident that the core viewpoints expressed in this post are correct, I haven’t shared drafts of this post with other people focused on operations, and so it’s possible I’ve missed important context from other perspectives. There is lots of simplification here; many details and complexities are brushed over to make this more accessible. A good deal of this post is more opinion rather than clear cut fact, so view this more like an op-ed.

Feel free to skip all the examples if you like. They are here for context, but you can understand the core ideas decently even if you skip over the examples.

Caveats, limitations, etc.

I don’t view myself as an expert on the field of operations. Thus, you should view this post as coming from a fairly well-read individual with a decent amount of practice, not as a highly authoritative account from a person with world-class training.[1]

Overview

I'm going to provide a brief overview of what operations is and what operations management is, mention some gentle critiques of how operations is viewed in EA, give several examples of operations management in different contexts:

- a factory with materials coming in and products going out, which is a very classic situation for operations management.

- a sandwich shop, which serves to show how operations management can be applied to non-industrial situations.

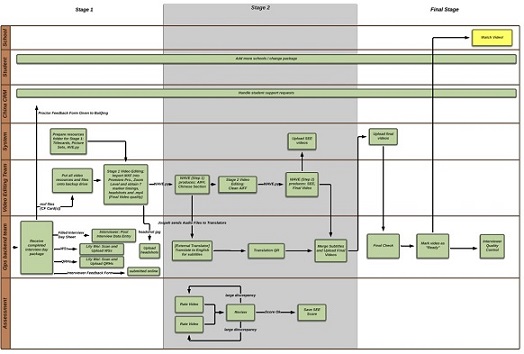

- a “digital factory” of video production, which demonstrates both the extent to which the details of the situation matter as well as how easily systems can get complicated.

- a health clinic, showing a very realistic application of operations management in which the resources flowing through the system are people.

- the Berlin airlift, a historical example in which operations management saved lives.

I’ve purposely included many examples in order to illustrate the wide variety of what operations and operations management looks like in different contexts.

Why I wrote this

I wrote this for a few different reasons:

- I have seen a few pieces of writing within EA that conflate operations work and personal assistant work, and I want to prevent that from happening. I’ve also seen multiple job postings titled as operations managers that list personal assistant-type tasks. My stance is this: in certain scenarios you could make a reasonable argument that a personal assistant falls within the operations team/department, but in general we should not be conflating PA work with operations work. An operations manager should be creating/designing systems and processes, optimizing existing processes, establishing new processes, and generally helping business flow smoothly. An operations manager job generally shouldn’t include updating social media pages or handling someone else's emails/calendar/travel schedule.

- My rough impression is that people in the EA community (as well as people in general) seem to have a hard time describing what operations management is. The 80,000 Hours article doesn’t mention resource flows, or bottlenecks, or other standard/common concepts in operations management. I'm hoping that by providing several examples of operations management in distinct contexts I can help to solidify the concept a bit, specifically the manufacturing/production aspect of it.

- I very much enjoyed eirine’s two posts on So you want to do operations, and I wish that there were several more posts in that series giving more in-depth descriptions. I was disappointed to learn that the series ended after only two posts.

- If people in EA want to describe “everything that supports the core work and allows other people to focus on the core work” then I’d recommend using a term other than operations, because operations already has a meaning in the context of running an organization. General management might work, but I think that administration[2] seems to fit the meaning of supporting the core work. I’m guessing that 80,000 Hours choose not to use administration due to optics: people tend to associate administration with administrivia rather than with all of the work needed to run an organization. While I don’t think it is realistic for me to expect the entire EA community to change their terminology, I at least want to make the case for rectifying names.

Operations

EDIT: I came across a more clear and more concise definition that I'm adding to this post. Operations is "how the organization’s products and services are produced and delivered."

Operations is the core work of a company, and generally involves transforming inputs into outputs. Thus, what counts as operations will vary a lot depending on an organization's specific context and circumstances. I strongly agree with the claim that operations is not a single thing. However, what I am claiming here is different from the common perception within EA that operations is everything that supports the core work and allows other people to focus on the core work. As far as I can tell, this perspective originated with the 80,000 Hours article on operations.

I think there are three things[3] that make understanding operations a bit trickier than understanding marketing, finance, or other common business functions.

- First, there is often a difference between what is considered operations and what the labels of departments, teams, and roles are. I’d encourage people to determine whether or not something is operations by looking at the facts and circumstances, not by the label given it. So the difference between what operations is and what an organization calls operations tends to cause confusion.[4]

- Second, the "border" between what is operations and what is not operations is quite fuzzy. You can make a reasonable claim that many things in an organization which contribute to the core effort of the company count as operations, but my understanding is that generally people don't take it that far.[5] As far as I am aware, there isn’t a clear/strict standard regarding what counts as operations, and it often depends on how “zoomed in” your current perspective/lens is.

- Third, people get confused about operations because it often isn't named/acknowledged. Many students studying business learn at least something about operations, but they might learn it in a class called Logistics, or in a class called Statistical Methods, or in a class called Management Economics. Similarly, people often do operations work without having the word “operations” in their title, and often without even knowing what operations is. The title of General Manager is generally (although not always) an operations manager. The rough impression I get is that many people don’t encounter the term or the label of operations until they learn that a company has a COO in addition to a CEO.

Operations Management

If operations is just "doing the work," is operations management just all aspects of management (planning, organizing, leading, and controlling) that relate to the core work? Not quite. If an organization is only as effective as the systems that comprise it, then operations management wants to improve those systems. We are trying to do more with less, an idea that I think should appeal to the "effective" part of the effective altruist mindset. I like to think of operations management as optimizing flows of resources in and out of a system. An important aspect of this is that operations management tends to focus more on managing processes rather than on managing people. Thus, it is possible for someone to be a people manager within an operations department even if he/she isn’t doing operations management.[6] If you prefer a slightly more formal definition: operations management is about “identifying processes that need improvement, pinpointing bottlenecks in the system, and determining how best to alleviate them and improve processes.”[7]

So while there are some tasks that fall under nearly all management roles (giving feedback, scheduling work, sharing information, etc.), an operations manager generally focuses on improving and maintaining systems. The goals for an operations manager could be:

- to maximize the outputs per each unit of input

- to maximize the outputs per process performed

- to maximize the outputs per minute/hour/day

- to minimize inputs per each unit of output

- to alter the processes so that we can turn inputs into outputs faster, without any reduction in quality

- to alter the processes so that we can turn inputs into outputs at a higher quality, without any reduction in speed

- to figure out how to take a machine off the assembly line for several hours for maintenance while minimizing the negative impact on production[8]

In a simple sense you can think of operations management as working to improve the input-output ratio. Here are some hypothetical (but realistic) examples of this actually being applied, several from my own work experiences:

- How many hours of effort do our researches have to devote in order to produce one research publication of our defined quality? Are there systematic differences in different research teams' processes? Are there easy distractions that we can solve (such as a researcher spending 5% of her time handling reimbursements)?

- How many hours do our teachers use to produce a single lesson plan that meets our standards? Are there resources we could provide once, preventing each individual teacher from Googling around for their own resources every week?[9] Could we train them all on the same tool and ask them to create lesson plans in a standardized format to make sharing easier?

- How can we feed 5% more people at our event while using only 2% more resources? Could we negotiate prices, find new vendors, or make sacrifices in other areas in order to satisfy this constraint?

- When recruiting new employees is it possible to reduce the number of interviews without a proportional reduction in the assessment's accuracy? Is the CTO wanting an informal chat to get to know the person adding any value if that candidate has already spoken with the manager and the CEO? What additional information will we gain from inviting this person to lunch, and what is that information worth to us?

You can imagine how someone who studied engineering would do well in operations management roles, but from what I've seen, operations management roles tend to require excellent communication skills and people management skills, and not much in the way of mathematical ability.[10] I find it very similar to being a project manager: you need both a baseline of understanding of the business/product, as well as excellent organization and excellent people skills. In my view, project management and operations management are very similar fields/roles, with the main difference being that operations are continuous/ongoing while projects have specific start dates and end dates.

Examples

Physical Factory

The classic example of operations management is the idea of a physical factory, with materials going into the factory, various things occurring while the materials are in the factory, and materials going out of the factory. Production and manufacturing are the contexts in which operations management was born as a field, although in the early days it was called scientific management.

I worked in a factory that made iron castings for automobiles when I was 18,[11] and while I had very little insight into the management of the factory, I was aware that there were many different stations in the factory between where we received raw material and where we shipped out finished castings. Looking back, I can realize that someone must have planned out the various resources (both machines and humans) for each stage, and that there was probably regular monitoring to see how things could be done better. If the factory could run a particular station faster, they would. Very simplistically speaking: a factory generally wants to increase the throughput of the system by resolving bottlenecks, up until just below the limit at which the speed causes problems.[12] You generally don’t want the system to be too efficient, because that means that the slightest variation causes blockages or cascading failures.[13]

In some cases, maybe the additional profits more than compensate for the costs of extreme speed, such as faulty products causing losses of $X/hour but additional production increasing earnings by far more than $X/hour. Like many things in life, balancing tradeoffs is important.

While producing more iron castings per day doesn’t seem particularly impactful, think about a factory producing plant-based meat, or COVID vaccines, or respirators: better operations could make the difference between preventing Y deaths per day or preventing 1.2*Y deaths per day. So if you want a "soundbite" here is a simple takeaway: having better operations means achieving more per dollar (or per hour, per person, per resource, etc.).

Sandwich Shop

I remember looking at the Introduction to Operations Management course on Coursera back in 2012 or 2013, and I was introduced to the idea of using a sandwich shop to learn about operations. I thought it was a good example, so I'll recycle it here. If you walk into a Subway restaurant (a chain of fast food restaurants that produces sandwiches in an assembly line), there are a few different stations that resources will flow through before the system produces a finished product. Here is my rough outline (note that I use the word "system" here to mean something like "all of the inputs/materials, processes, and outputs involved in making a sandwich"):

- Information from the customer about the desired bread and desired type of sandwich is put into the system

- Bread is put into the system

- Someone cuts open the bread

- Someone adds fillings

- Someone heats up the sandwich

- Someone adds more fillings

- Someone adds sauces/spices

- Information from the customer about drinks, chips, cookies, etc. is put into the system

- Customer pays for and receives sandwich, plus any drinks, chips, cookies, etc.

At first glance that looks far more complex than I need to make a simple sandwich, but what if we have only three employees and high demand from many customers? In that case, we want to make sure that each employee is doing the optimal task. I wouldn't want to have one employee getting bread (which takes only a few seconds per sandwich), a second employee handling the payments (which only takes a few seconds per sandwich), and the third employee adding the fillings and asking customers what they want (which usually takes many more seconds). That would involve two of the people standing idle for much of the time.

An added complication is that each sandwich is customized. In a system where all outputs are identical it is much easier to tweak and adjust processes in order to improve the system. But when every single item is unique, optimizing gets much more challenging. Maybe the first customer only needs a few toppings on her sandwich and doesn't want it heated up, but maybe the second customer wants a sandwich with many toppings and wants her sandwich toasted, is indecisive about what sauce she wants and asks a few questions about the different sauces, and then takes several seconds deciding what kind of cookie she wants while contemplating if she should instead donate the money because she feels guilty spending money on a cookie. Thus a general principle is that the more standardized the inputs and outputs are, the easier it is to optimize the system; the more customized or variable the inputs and outputs are, the more complex and the harder it is to optimize the system.

Video Production

In 2014 I started to work for a startup that did in-person interviews with international students applying to US schools.[14] This startup had about 25 employees, falling into the 10–100 range mentioned in this 80,000 Hours article. The products were fairly standardized, but we did have a few options that the students could choose that would affect how we processed the videos. I think of it roughly similar to the factory, albeit this was a digital production system rather than a physical production system.

So with a high level overview it seems straightforward, but each of those steps contain a lot of detail. Conduct the interview covered:

- designing and testing a standardized interview

- setting up the camera and the microphones, making sure the room had a blackout curtain, and other general set up for the space

- make sure the pictures are printed and that the interviewer uses the assigned picture for each interview

- making sure the student/parent got clear information about when/where to go for the interview

- having the interviewer do a clear hand-off of the video card which contained the video data

- as well as the background work of hiring, training, and scheduling interviewers.

Split the video into several different items meant

- Extracting the section of the video that wasn't in English (part of the interview was conducted in the applicant’s native language), converting it to an audio file, listening to that audio file and typing out the English equivalent in timestamped subtitle file,[15] having a second person double check the accuracy of the subtitles, then merging them onto the main video with the proper timing.

- Creating a title card with the students name, the date, the location of interview, and other standardized information.

- Chopping off the first few seconds and the last few seconds of the main video, compressing the video file down to our standard format, converting it to a different file type, adding an the title into the beginning, adjusting the cross-transition between the title card and the interview to get the fade in looking good.

- Making sure the correct picture gets faded in on a designated section of the screen at the time right when the applicant is handed the picture, and faded out when the picture section is finished.

- Having someone review the final product to make sure no mistakes were made (such as subtitles synced improperly or a wrong picture up on the screen).

As you can imagine, if people were as consistent as computers, many of the above steps wouldn't be too troublesome. But sometimes the interviewer used a different picture and neglected to update the data, or a type-o would get into the subtitles and we'd have to re-type them and re-merge them with the video file, or sometimes there was background noise from construction in a different part of the building and we had to use software to reduce the excess noise in the file, or sometimes someone forgot to handoff their task to the next person when they finished and it languished "lost" for a period of time. All of these issues took extra time from staff, which was a valuable resource.

The occurrence of these problems could be reduced, but you can never reduce risk/variation down to zero. A big part of operations management in a production context is foreseeing what might go wrong and putting in place a process to prevent it. We used in-process reviews before merging the component parts into a final video file, and then another in-process review before 'delivering' the videos. Sometimes these kinds of processes can be simple as a checklist, which we had each interviewer go through at the end of an interview day.

Similarly, if tasks all had rapid turnaround then planning would be easier, but in reality it took computers several hours to export video files, and it took staff multiple hours to listen to audio and write English subtitles. Thus, the work was somewhat “spikey:” the video editor was very busy for a few hours doing the manual part of video editing, and then once he set the files to export the process would continue without any manual intervention; he was done working, but the staff who handled the next step couldn't start yet. We sometimes had situations in which we had salaried staff in the office ready and willing to work, but there wasn't any work to be done. Ideally, this should never happen, but in reality I imagine that a lot of small organizations and organizations that have staff without much professional competence in operations have encountered scenarios like this. This leads us toward another idea: details and context matter. You often can’t make a system better unless you understand the specifics of the work being done and the context of the business environment.

A good operations manager will find ways to increase slack in certain parts of the system, such as paying for additional computer processing power or shifting the time that people start their workday. There are always ways to relieve bottlenecks. Or you might find good "back burner" tasks for staff to do when the main tasks aren't available, such as preparing training documentation or researching new software. You can train additional staff on video production so that when needed they can increase capacity at that "station." This is related to the idea of capacity flexibility: the ability to adjust the total production capacity. You could attempt to speed up or slow down certain tasks or certain stations to make the flow of resources more steady, reducing peaks and valleys (very similar to the idea of flattening the curve in the context of COVID-19).

Health Check Clinic

I recently did a health check to make sure that my diet wasn't causing me to be short of any important nutrients, and the experience made me think of operations. This health clinic took up a full floor of the building, and there were many different options to choose from on the "menu:" various types of bloodwork, ear exam, eye exam, and so on. There were probably about 25 or so different stations. As a client, I had paid for the service at certain stations, and the organization has a goal of allowing me (the resource) to flow through these stations as quickly as possible (without going so fast that it causes problems). If there is only one client going through the system and all the stations are just sitting there idle and waiting for the client, it doesn't particularly matter which order you go through the stages in. However, if we make it more realistic:

- there are multiple clients.

- each client signed up for a different combination of services.

- each station requires the client to spend a different amount of time there before it is completed, some take 30 seconds, some take 120 seconds, some take 600 seconds.

- the time for each station is not standard, but is instead probabilistic. Maybe most people take around 120 seconds for the ear exam, but not everyone takes exactly 120 seconds. There will be a minority of people that have a problem and need considerably more time at a station.

- many other clients are going through the various stations, and you aren't able to strictly control where they go to next. Even though the optimal path in a particular situation might be ABC, this client decides that he wants to get the bloodwork out of the way first, so he does the suboptimal BAC. That client might decide that they want to step outside for a smoke break before starting the next station. So the situation is somewhat dynamic/in flux.

Thus, we have what I view as a classic/standard operations management problem: given many flow units (in this case, people) flowing through a system of many stations, and each item has its own combination of stations that it needs to flow through, and each station is unique, in what order should each resource go to each of it's stations?

I don't know how the health clinic solved this on the back end, but on the front end they had a mini-program that a client could register with to show all of the stations the client had signed up for, which ones were already completed, which ones were yet to be completed, and it had a large prompt at the top stating which station you should go to next. As long as people were using that system and generally following the instructions, it seems to do a pretty decent job at solving the "you can't strictly control where people go problem." There were also very proactive staff who would approach a client that didn't seem to be waiting in line, look at the clipboard the client was holding with all the information regarding that client, and instruct the client what room they should go to next. I don't know what standard/heuristic/algorithm they were using, but overall I was quite impressed with how smooth the experience was.[16]

The Berlin Airlift

The final example I'll give is one that I have no personal experience with, but which I found inspiring. When I learned about the details of the Berlin Airlift is when I realized "operations management can save lives." You can read about a lot more details in When You Get a Job to Do, Do It, which I do recommend for people who want to learn more about operations.[17] The vastly simplified explanation the Berlin Airlift is that people in West Berlin were isolated, so food and other supplies were flown to them in transport planes. If they needed more food than was flown in, they starved to death.

Lt. General William H. Tunner was one of the core people responsible for improving this system. He is no Norman Borlaug, but did manage to prevent a lot of deaths. He got more resources into the system, he improved safety standards, established ambitious targets, and generally made a lot of changes that enabled the delivery of more supplies each day. His reaction to the Berlin airlift prior to his involvement stands out to me, and it has parallels with the idea of operations work not being glamorous/sexy:

“Pilots were flying twice as many hours per week as they should, for example; newspaper stories told of the way they continued on, though exhausted. I read how desk officers took off whenever they got a chance and ran to the flight line to find planes sitting there waiting for them. This was all very exciting, and loads of fun, but successful operations are not built on such methods.”

There is a lot you can learn from studying the details of the Berlin airlift, but one main takeaway for me is that operational excellence really can make a massive difference; depending on how you do it, it isn't just a miniscule efficiency gain here or there. Optimizing processes can make a huge difference. And depending on what your processes do, operations management can save lives.

Wrapping up

If your mission is to get food to starving people in Berlin, or to deliver insecticide-treated bed nets, or to pass legislation regarding the treatment of caged chickens, or to cure parasitic worm infections, or to mitigate global catastrophic risks, then good operations can help you save lives. It will let you do more with less.

If you want to learn

One of the nice things about operations management is that it is often just a mindset, a way of looking at things, and an attitude that makes a person competent.[18] You should always be thinking about how to increase the efficiency of systems, and you can look at many (although not all) systems as variations on the classic factory: inputs, outputs, and items flowing through. I don't know how mindset/outlook can be learned and trained other than by being put in an operations environment, but I bet that it can, and I’m hoping that people smarter than me can share some ideas.

I also want to note that one difficulty with learning operations is that understanding the applicability is challenging if you haven’t had relevant experiences. I think this is similar to how people say you get more out of an MBA if you have a few years of professional experience, rather than if you start an MBA directly after a bachelor’s degree. Many of the YouTube videos or books that I have found helpful, I wouldn’t have gained very much if I had encountered those materials at age 22 (when I was recently graduated with no white-collar work experience), but because I encountered those materials roughly from ages 26 to 33 (when I had relevant work experience) I was able to quickly understand how these concepts were useful. It is hard to understand how Six Sigma or Kanban or queuing theory might be useful without sufficient context.

There is a bit of technical knowledge about how to do process analysis, how to use digraphs, and a few other tools, and there are a handful of concepts and equations relating to constraints that are helpful to know. You should have a basic understanding of statistics (including probability, distributions, and sampling), but you don’t need a degree in stats by any means; the knowledge you gain from StatQuest and Khan Academy should be enough for many situations, and I imagine that an introductory level statistics course in a university should be sufficient. There are a lot of domain-specific skills that are very important depending on the context of your specific organization and industry. Microsoft Excel and managing people are the two skills that I think are highly transferable, but I can easily imagine scenarios in which other general skills are important.

If you want to learn more about operations, there are plenty of good books you can read[19] and some decent playlists of YouTube videos to watch.[20] You should try to gain at least a superficial level of familiarity with the Toyota Production system and with Six Sigma; I also found aspects of Lean, Kanban, and Scrum to be useful. The Introduction to Operations Management course on Coursera does a fairly good job of introducing the concepts and tools in a slightly more quantified way, although I think that the content/lectures are quite dull. There are also masters degrees at various universities if you want to really commit to it fully. Most MBA programs will give you at least some knowledge of operations, and I’m guessing that a bachelor's degree in business administration would also give you at least some useful knowledge of operations. If you reside in the USA you can get a degree online part-time at WGU. If you want something more formal/organized than self study, but more accessible than an MBA or a masters degree in operations management, Harvard Extension School offers a graduate-level course in Operations Management, and there appear to be no prerequisites.[21]

Watching project management videos and preparing for the PMP exam is not identical to operations management, but I’ve found that there are a lot of overlapping ideas between project management and operations management. Daniel Kestenholz’s document on Professional Development in Operations has some useful resources also.

I really do think that a lot of what is useful for operations management is simply general professional and management skills, which are often picked up on the job or by reading business books. That is how I learned about a lot of stuff: I had a job in which these things were relevant, and I wasn’t given any training so I Googled and read and learned. There are a lot of miscellaneous little concepts (clock-building and time telling), techniques (vlookup and index match, takt time), and tools (Gantt charts, KPI trees) that are broadly useful in business/work.

I’d be open to putting together a rough syllabus on operations management, so please let me know if you’d be interested in something a bit more organized than the above few paragraphs. But even if that never happens, I hope that the above few paragraphs are a helpful starting point for people who want to learn more.

A note on personal assistants

Being a personal assistant could be considered part of the operations department in some companies, but personal assistant is not operations in the same way that Asia is not continent[22]: it is an item that is sometimes included in a category rather than the prototypical example that represents the whole category. If you asked Operations managers at multinational companies or university professors who teach operations "is a personal assistant considered operations work?” they would answer “no.”

Things that could feasibly be considered operations

Here are some examples of things that I think might feasibly be considered operations in different contexts. Try to think of each of them as a factory, with inputs, various processes, and a finished product as an output.

- sourcing and filtering candidates in a recruiting company, then passing candidates on to your client company

- producing/doing research in a research organization

- producing/procuring/shipping insecticide-treated bed nets

- running a fellowship program or some other bootcamp/training program (which takes an “input” of curious and interested people and produces an “output” of aligned/skilled/informed graduates)

- recording and editing podcasts on topics such as why wars happen or what an operations mindset is

- creating content for a news website (creating and delivering the product that the customer is paying for)

Thus, if someone tells you "I work in operations" or "I am an operations associate" or even "I am an operations manager" they really haven’t told you much about their job; you don’t know what they do. It varies widely depending on the details of the organization and industry.

- ^

I've done Coursera courses, watched YouTube videos, read books, and worked as an operations manager. I've read relatively few academic articles related to operations management, I don't have a degree in operations management, and I have never received formal training or education in operations management. I did take a few online courses from eCornell, but while I learned a little I felt they were not worth the money and I wouldn’t recommend them. Almost all of my knowledge/skill in operations management comes from independent learning and from my work experience over a period of roughly six to seven years.

- ^

Depending on which dictionary you want to reference, administration means “the management of any office, business, or organization” or “the process or activity of running a business, organization, etc.” or “the management of a government or large institution.”

- ^

I came up with three things, but there might be more. These are just categories that I came up with on my own; this categorization is not some kind of widespread convention or standard view.

- ^

A Floor Manager at a department store might not be in an operations department in the company org chart nor have the term “operations” in his/her job title, but he/she likely is responsible for operations management tasks. A university generally doesn’t view students as inventory, but an operations analyst likely would: each student is a flow unit moving through a process. A junior diplomat conducting visa interviews all day doesn’t think of him/herself as working in operations, but taking a more zoomed out view you can see how the interview is a repeated process with clear inputs and outputs, and you can find ways to optimize this process to increase the flow of people through the system. I think that this video gives some nice examples and context if you want to explore this idea a bit more.

- ^

You can make a decent argument that the janitor taking out the garbage is necessary for the core functions of the business to go forward (because nobody could work if the floor was covered with garbage), but I think you would be hard pressed to find somebody who considers the janitor to be part of the operations department. Conversely, a waiter and a chef in a restaurant would both easily fall within operations, but a casual observer likely wouldn’t consider either of them to be different types of operations associates: they would be front of house staff and kitchen staff.

- ^

As if we really needed something else to make the concept of operations more ambiguous and confusing.

- ^

This is a quote from Natalia Santamaría, which I am excerpting from an online course she taught through eCornell. The course cost several hundred USD, and I gained very little from it, so I do not recommend it.

- ^

I'm using the language of industrial production here with “machine” and “maintenance,” but you could easily substitute the words “employee” and “training.”

- ^

This might seem silly and overly simplistic, but it really can help to have centrally curated and provided resources. I can't count the number of scenarios in which Employee_A needs to find or create a [THING] as part of his job, and Employee_B also needs [THING] for her job, and Employee_C has been doing this job for several years and has [THING] he likes but he hasn't bothered to share it. Instead of each person spending X hours per year, a single person could spend X hours and then make that resource accessible. This can sometimes be as simple as template documents with some information prepopulated or enforcing naming conventions on files.

- ^

A big caveat here is that I've worked with small teams in which there wasn't much mathematical ability needed, so my perceptions are of course very shaped by the particular circumstances that I've experienced. From what I can tell, most master's programs focused on operations management tend to use a lot of statistics. My rough impressions are that as long as you are comfortable with algebra and intro-level statistics you probably have enough mathematical ability. But I imagine that the specific context you work in will affect this a lot, and that it might vary widely from one context to another.

- ^

I don't know how many EAs have done blue collar work, but I get the impression that I am in the minority. Did all the rest of the EAs have formal internships at fancy organizations while I wore steel toe boots and drove a forklift?

- ^

Problems from operations being too fast could be things like workers getting injured, machines getting damaged, faulty products being produced, insufficient slack in the system to deal with unexpected peaks of demand, etc.

- ^

This is a whole big topic, one that I would love to learn more about. If you have constant inflow then you don't need to worry about slack. But it is more common that inflow is variable, so you have to balance spending too much on having unused capacity when you have low levels of inflow against running a more lean operation and being unable to process higher levels of inflow.

- ^

We conducted the interviews in-person, showed the student a picture during the interview while discussing the picture for a little while, video recorded the interview, split the video into several different parts, and then recombined the parts and uploaded the finished product to a portal from which the admissions officers could watch the video at their leisure. The end product was mainly to allow admissions officers to verify the applicant’s language ability, but the admissions officers wanted to see the applicant’s personality also.

- ^

This would be the inverse of sight interpreting, but I don't know what the actually name for this work would be called.

- ^

Of course, if any system can appear smooth when it is operating far under capacity. Imagine if the sandwich shop only has two employees. That is fine if there are 500 customers that are spread out evenly throughout the day, but imagine the backup if a big group of customers all arrive for their lunch break within a single 30-minute timeslot.

- ^

Chapter 3, which is about William Tunner’s experience before the Berlin Airlift, serves as a really good case study of what operations management is, and it also great inspiration for how big of a positive impact a good operations manager can make. The whole book is free online. Chapter 3 is only 10 pages.

- ^

This is a simplification and is perhaps less true at the more advanced levels, where there are specific formulas to be applied in order to predict optimum levels for various things. However, my guess is that at the level most people in the EA community would do operations management work, this simplification is accurate enough to be useful.

- ^

The Goal is always recommended as a starting point; it is sub-standard as far as novels go, but quite good in introducing the reader to a variety of operations concepts. Chapters 1 and 2 of High Output Management also serve as a good non-technical introduction.

- ^

While Mathispower4u has a ridiculous name, it does have a good introduction to scheduling playlist, and King's University College has a series of lectures on Operations Management. I have been pleasantly surprised by Narendar Sumukadas’s videos on operations, and despite being nearly a decade old and having lower audio quality, I think they do a quite decent job of introducing a variety of concepts.

- ^

You don’t have to submit an application essay or any test scores to take courses from Harvard Extension School. I think of it like the community college of Harvard University: all you have to do is register in their system, sign up for the course, and pay the tuition.

- ^

People generally have different definitions of how many continents there are, depending on school systems and cultural conventions. Whether you think there are 4, 5, 6, or 7, there are reasonable arguments to be made to support those conventions. Nobody starts a business named Continents Solutions Incorporated that only focuses on Asia and ignores all the other continents.

- ^

I adapted this definition from a test prep book: the Mometrix PHR Study Guide, by Matthew Bowling.

Thank you for writing this. I work as an Operations Consultant and find that EA orgs use the term ‘operations’ to refer to roles and tasks that aren’t deemed as operations in my area of work. I definitely think a lot of the skills I’m picking up in for-profit operations are transferable to EA ops roles, but the core of the roles are quite different.

As Operations Consultants our aim is to make organisations more effective / efficient, eg. by:

There are really nice parallels between operations work and the fundamentals of Effective Altruism so I’m excited to see if operations as described in this post can have more of a place in EA!

Also happy to share more examples of typical operations work but think the above ones, and definitions, are good.

I'd love for you to share more examples of operations work, if it isn't too much trouble. I find that when I am trying to understand a concept or an area, having more examples is generally quite helpful. Often in educational contexts only one or two examples are shared, which can cause the people learning to overgeneralize from a non-representative sample, or to "overfit" in a sense.

Sure! Here are some examples of high level questions you might solve as an Operations Consultant:

Operations management and project management often have substantial overlap in activities and methods. However, one key distinction is that "operations" typically represent ongoing or repeated activities (such as running a factory or a manufacturing line within a factory), while "projects" are temporary and finite (such as conducting a research study on whether the factory should make a particular new product). See, e.g., https://www.northeastern.edu/graduate/blog/project-management-vs-operations-management/. (I used to work at a consulting firm where there were many project managers running short-term research or software-development projects for clients, and a few operations managers responsible for continual business functions such as invoicing clients and paying employees of the consulting firm.)

Right, other ways I've heard this described is operations is Business as Usual (BAU) and projects have a start date and end date. I've seen this important distinction when it comes to budgeting as BAU will be funded first with a certain % uplift of last year's spend. Project costs tend to be more of a stab in the dark as it will be something that hasn't been done in this iteration before (e.g. this location or population segment) and whatever will fit in the remaining budget plays a large selection factor.

Now programs....that's like having your cake and eating it too.

"One of the nice things about operations management is that it is often just a mindset, a way of looking at things, and an attitude that makes a person competent.[18] You should always be thinking about how to increase the efficiency of systems "

This mindset seems a strength that i believed was a weird quirk. I tend to notice and want to experiment ways to improve or automate systems.

"I also want to note that one difficulty with learning this is understanding the applicability if you haven’t had relevant experiences... It is hard to understand how Six Sigma or Kanban or Queuing Theory might be useful without sufficient context."

This point helps me look at my past experiences in a more positive light. The years I worked in 3-6 month waterfall development projects seem inefficient and wasteful. We could have solved and prevented many more problems with SCRUM, ex better team collaboration, getting user feedback sooner and adapting to change.

These experiences help me see the learning's potential more clear than I may have before experiencing the inneficincy of waterfall.

I think this post is excellent overall, but I do want to register a disagreement with your bid to separate operations work from the work that PAs do in most small nonprofit organizations. You have a keen observation about how the nature of operations work changes with scale: at top levels of a multinational corporation, the notion of a senior operations executive doing PA-style work is ludicrous. But for most EA organizations, that comparison is kind of nonsensical; we're talking about small outfits with 2-6 staff members and a mishmash of interns, contractors, volunteers and other loosely affiliated workers, not a 100,000-person behemoth with offices around the world. In the context of a small nonprofit, the proportion of operations work that looks like PA work is typically much larger than is the case in a huge company like that. Similarly, I disagree with statements like "You can make a decent argument that the janitor taking out the garbage is necessary for the core functions of the business to go forward (because nobody could work if the floor was covered with garbage), but I think you would be hard pressed to find somebody who considers the janitor to be part of the operations department." In my experience, organizations (such as schools) that hire janitors consider them maintenance staff, they are situated in the Facilities department, and Facilities is overseen by the COO or equivalent.

I think you are right that there can be a lot of overlap between the type of work that an operations associate/junior staff does and the work that a personal assistant does. My main push is that I don't want people to conflate the two. Seeing job descriptions for "operations managers" that involve managing a boss's calendar and handling emails for the boss made me think of how frustrated a person would be to apply and accept a manager-level job only to be given menial tasks, similar to what was written in Senior EA 'ops' roles: if you want to undo the bottleneck, hire differently. Nonetheless, I think you point stands that at a small team the border can be quite fuzzy.

Regarding the janitor, you make a good point. I had thought about my own experience working with small and medium enterprises. I hadn't even thought about the facilities department being overseen my the COO, but now that you mention it it makes a lot of sense.

EDIT: An Operations Manager role at Open Philanthropy describes the work as including:

Hi!

Great post, thanks for writing. I also found your previous post on hiring also very helpful. I'd be very interested in a syllabus of key concepts and materials. Even something low-effort (ie - a google doc with a list of terms/concepts to google and a list of general materials) would be useful. Please let me know if there's anything I could do to make this move forward. Thanks!

Thank you for writing that post, it really resonated with me. I worked a lot in industry projects with a students group that was doing lean / kaizen projects with partners from indistry so that students could get a feeling of how to optimize processes going from current state to a planned state using PDCA-cycles. I am happy to find other people with that operations mindset in EA.

This was incredibly helpful. I have been struggling with this ambiguity of 'operations management' in EA as I am in the midst of my career planning process. Specifically, what I have been wrestling with is that (1) I am incredibly excited about meta-thinking of processes, streamlining, and functioning as a multiplier of high-impact output, and think such a role might be a great personal fit for me, but (2) I have a strong , innate aversion to 'operations' work as described in Operations is really demanding (especially due to its overwhelming nature).

This way that 'operations management' is used in EA, where it seems to mix both types of work into one with the majority of responsibilities being the 'assistant'-like work, has actually led me to begrudgingly write off operations management as a career path for now. It does seem that, what I have seen in other comments as well, that most EA organizations might be of smaller size and hence there is no full-time position for the 'operations manager' as you describe it. That seems plausible.

I will be mulling over this some more as I am not entirely sure whether the types of operations manager positions you describe - those that excite me - are actually readily available in EA at this moment. If they would be, I'd be strongly considering them as my next move. Thank you for this helpful post!

Thanks for writing this post, I find it helpful to learn how operations is applicable in several scenarios which made me realized that my previous experience working as a sales and reservations coordinator/front desk customer representative in hotel/travel business were very operations-focused from both customer and production stand point.