Summary

Avoiding existential risk in the foreseeable future is a necessary but not sufficient condition to get good long-term outcomes. If we do get great outcomes, that almost certainly means there was a good reflective process which helped to steer us there.

Positioning the world to enter into such a reflective process is a proper target for action today. This complements the “Maxipok” principle of seeking to minimize existential risk. However, since we don’t yet understand the requirements of a good reflective process, we should not yet plan to commit to a particular version.

Meta

This post expresses some of my thinking. The thinking is in many ways not complete, but it’s been in that state for years; I've found myself several times linking people to private docs; and at some point I think it’s helpful to have something public, so I’m tidying this up and putting it out. Credit for having informed my thinking goes to a lot of people.

The post also stays at a relatively high level of abstraction in analysing existential risk and related areas. I think that in practice it's very important how these ideas intersect with what we're expecting with AI. But it's cleaner to keep the parts of the analysis which don't rely on particular empirical forecasts separate, so I'll leave discussion of AI for another post.

Distribution of futures

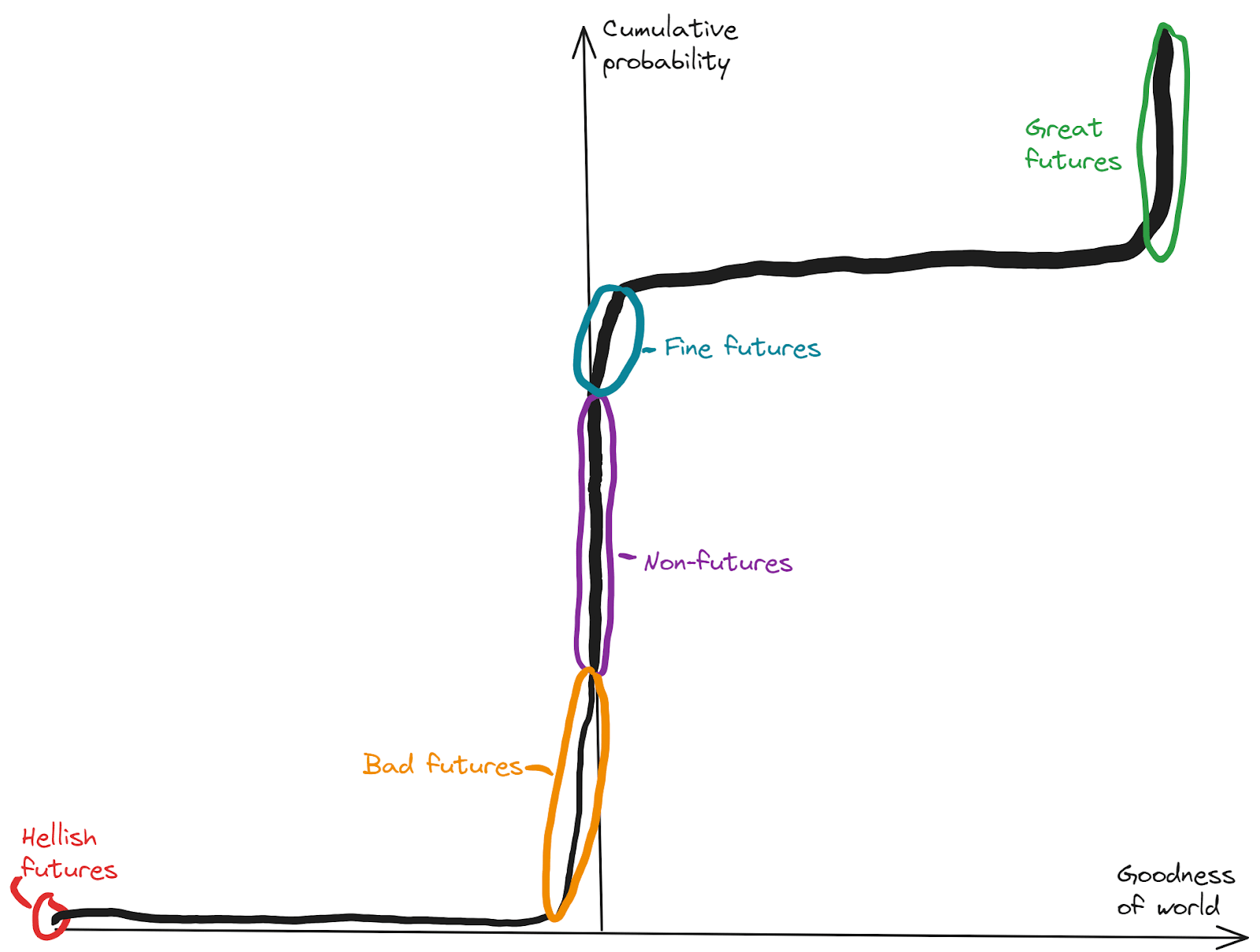

How good will the future be? Of course it’s extremely uncertain, and may depend a lot on the perspective it’s being asked from. But that doesn’t mean we can’t say anything. If I condition on some broadly-consequentialist axiology that I might come to endorse on reflection, here’s a cartoon showing very roughly what my probability distribution might look like, with all possible worlds arranged best-to-worst as you go top-to-bottom:

This isn’t supposed to be in the vicinity of precise; especially the goodness scale is not necessarily linear. But the key high-level features that I do (tentatively) stand behind, and want to draw attention to, are:

- There’s a reasonable probability mass on “non-futures”; things which are close to zero total value

- There’s a reasonable probability mass on “great futures”, which are all in-the-same-ballpark as good as each other, and all much better than ~anything not in this cluster

- There’s a small probability mass on “hellish futures”, which would be very bad

- There are reasonable probability masses on “fine futures” and “bad futures”, but the total goodness or badness of these is small compared to the great or hellish futures

- There is a little probability mass on things which are a reasonable fraction of the great or hellish futures — mostly corresponding to worlds in which the lightcone is divided in some way

- Trade means that the probability of such outcomes isn’t so high, and I’ll set them aside for now; however, I think that this would be a natural place to extend this analysis

- There is a little probability mass on things which are a reasonable fraction of the great or hellish futures — mostly corresponding to worlds in which the lightcone is divided in some way

What’s going on here? Basically I think:

- A lot of decisions have to be made correctly to get to something that’s within spitting distance of the best accessible futures

- These decisions are vanishingly unlikely to all — or even close to all — be made correctly by chance

- So the great worlds are ones in which there’s some decision-making process which is systematically making good decisions

- At this point it will likely get all of the decisions pretty-much right, and we’ll be in one of the worlds that’s basically getting things right

- (i.e. I mostly buy some version of the convergent morality thesis)

- Probably the value of such worlds scales to a first approximation with the amount of stuff that they can do good things with, and this is likely not to vary too much between future possible worlds (astronomical waste from delay is small in relative terms), so likely all of the great worlds are in the same ballpark as good as one another

- (There are definitely ways this assumption could fail, but I think it’s most-likely correct, so I’m going to run with it for now)

- At this point it will likely get all of the decisions pretty-much right, and we’ll be in one of the worlds that’s basically getting things right

- It’s not vanishingly unlikely to establish such a decision-making process, so there’s a not-vanishingly-small probability mass on these great futures

- This is taking a position in the direction of the convergent morality thesis

- Though for the conclusions that follow you don't need such a strong assumption as actually-convergent morality from adequate decision-making processes. It suffices that from our current epistemic position we are ~indifferent between various different adequate decision-making processes

- This is taking a position in the direction of the convergent morality thesis

To the extent we are concerned with the expected value of the future (& there are reasons not to go all in on this perspective! But for now let’s explore what it even says), it seems especially important to maximize the probability of getting such great futures (and to minimize the probability of hellish futures).

Horizons

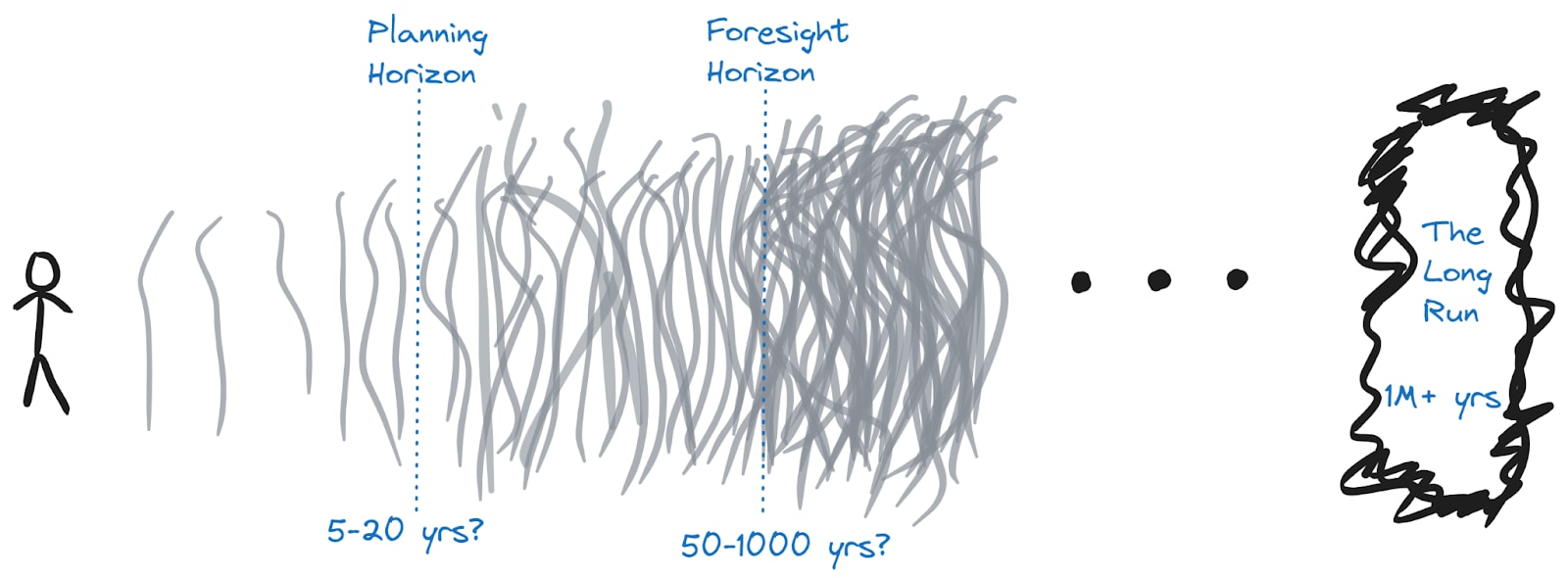

OK, so now we know what to aim for? Well, not so fast. Unfortunately it’s not very action-guiding to say “aim for great futures” because we don’t get to see (in time) how everything plays out, and the future is famously hard to predict. We can imagine the future as having a fog over it, such that it gets harder to see through the further away things are.

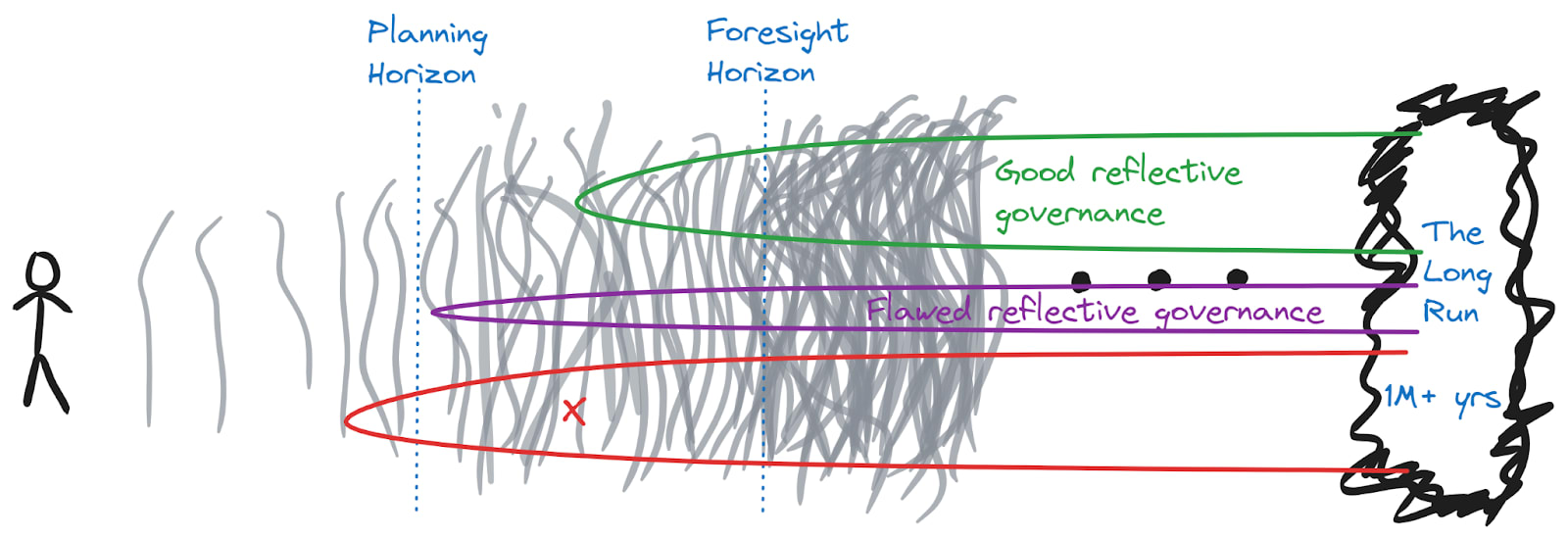

Here’s a picture of that, with a couple of semi-arbitrary divisions drawn on it to help us discuss the picture:

The Planning Horizon is, roughly speaking, the limit of our normal ability to make sensible plans and prepare for specific eventualities. We can get ready for things further away than this, but details are obscured by the fog, so normally we have to act via broader, less specific plans. Of course in practice exactly how far out it is will vary according to the domain, the person doing the planning, and the type of plan. But for illustrative purposes we can imagine that it usually occurs less than twenty years out.

The Foresight Horizon is the point past which we can’t really see anything in the fog. In most cases we can’t make meaningful predictions about the impacts of our actions beyond this point. There are (important!) exceptions where we have strong reason to believe something may be persistent for a very long time. But mostly I think it’s hard to reason about anything past a thousand years, and perhaps much sooner (especially if technological change accelerates, these horizons might all come much closer in calendar time).

Stable basins

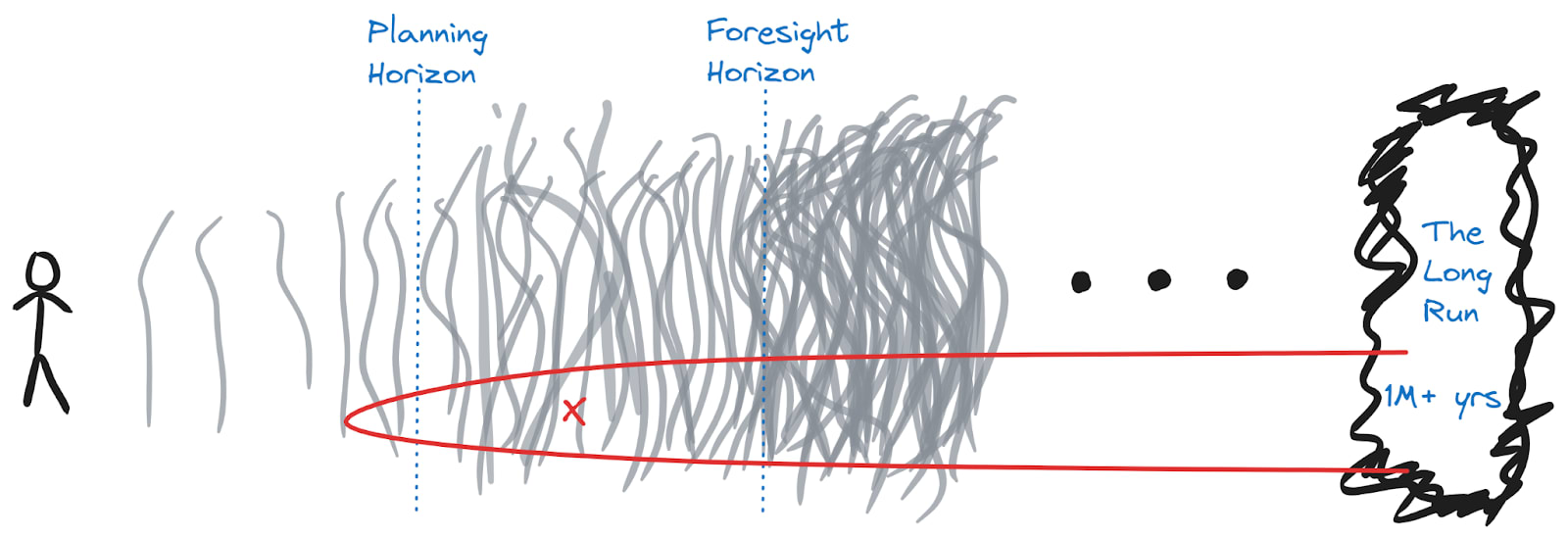

If we care about events far beyond the Foresight Horizon, how can we hope to have any predictable effects? Now we come to the exceptions. Some states of the world are highly stable and likely to persist for a very long time. The extinction of humanity is one such state. It would commit us to one of the non-futures[1], and we could be confident that this would continue past the normal Foresight Horizon. Understanding the world as a dynamical system, we can regard human extinction state, and existential risk more broadly as a basin of attraction — if we once enter the basin, we won’t leave, so this is predictive of long-run outcomes.

This is the basis (as I understand it) for the Maxipok principle. If everything else washes out in expectation, at least we can aim to have persistent long-term impact by maximizing the probability that things still look OK (i.e. not in the existential catastrophe basin) at the Foresight Horizon.

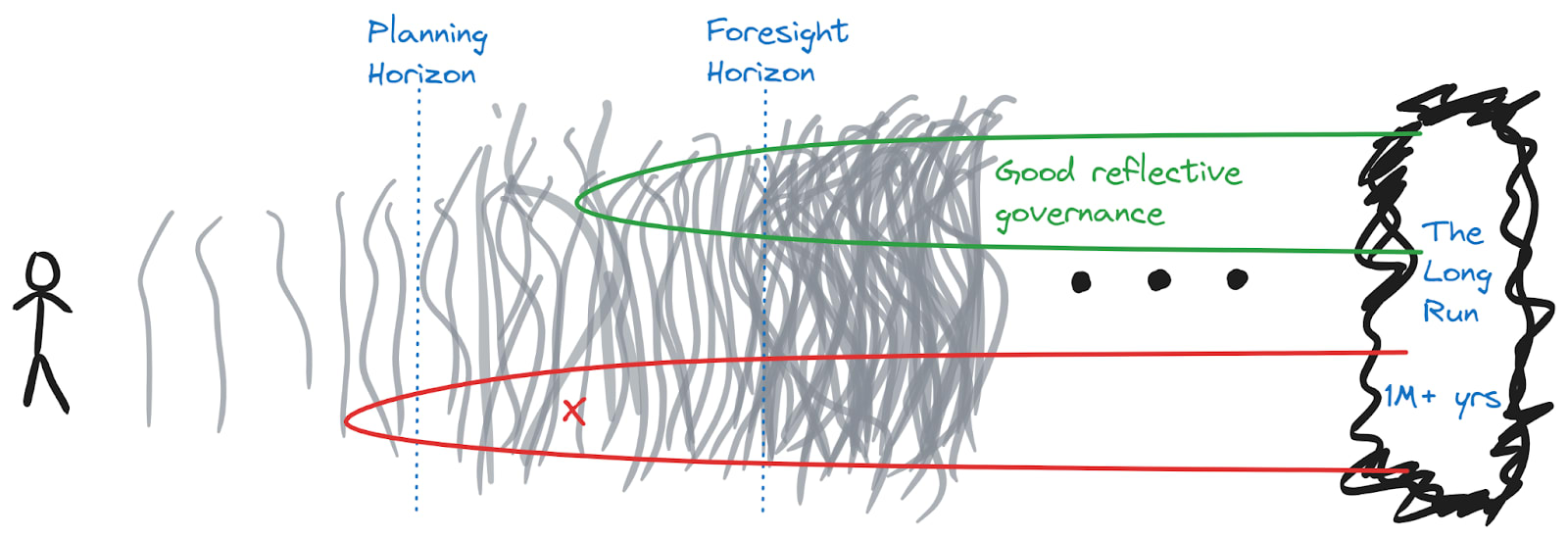

Good reflective governance

But now that we’ve got our eye on the possibility of basins of attraction — might there be others? In fact I think we’ve already considered one. I said I expected that all the great futures came about because there was a decision-making process making systematically good decisions. I think that having the future in the hands of such a process — or a good-enough forebear of such a process — would also function as a basin of attraction. It would be important by the lights of the decision-making process to ensure that the future it passed on was at least as well equipped (if not better) in the decision-making department, as well as that it avoided any major traps.

I will call this the basin of good reflective governance. The idea is that this is a region which has good enough reflective processes, and a good enough starting point, that it will eventually get itself to something great. This concept is close to that of the long reflection, in that the key feature is that there’s a lot of reflection that will be needed to ensure that things go well. I’m not using that term because it’s not obvious that “the reflection” is a distinct phase: it could be that reflection is an ongoing process into the deep future, tackling new (perhaps local) questions as they arise.

Now there are two legitimate targets: reduce the probability of falling into the existential catastrophe basin (before the Foresight Horizon), and increase the probability of making it into the good reflective governance basin (before the Foresight Horizon; I generally think it would be premature to try to rush there within the Planning Horizon).

What do we really know about the good reflective governance basin? Unfortunately, I think we don’t understand it terribly well. I am inclined to think that it’s not vanishingly narrow — I’m not too concerned that any humans except myself-in-the-moment-of-writing would be like paperclippers to me. But this is me gesturing at intuition, not giving a carefully reasoned argument. Still, if that is right, I know at least that there are some principles of good thinking that need to make it in, and also some foundational moral values. I don’t know what all of the things that are important to have included are.

Other traps

I don’t think we know enough to confidently specify points in the basin at the moment. For this reason, on the diagram above I’ve only marked the basin as starting after the Planning Horizon — I simply don’t think it makes sense yet to make active plans that would land us in the basin. And one thing which is concerning is that it’s not the only basin of reflective governance. The world could end up in the hands of a thoughtful paperclipper, or a reflective-dictatorship-that-ultimately-missed-what-is-valuable. In each case if it enters into the basin where the reflection of the steering intelligence determines what follows, we should not expect it to escape. These will mostly correspond to either “fine futures” or “bad futures” in the long run.

And since we don’t know exactly what ingredients are required for good reflective governance, the concern is that in aiming for the good reflective governance basin we might accidentally commit ourselves to something flawed. I’m rather more scared of missing ingredients than of accidentally including too many things in the initial setup — since, by presumption, good reflective processes can help to separate what’s truly important from what isn’t. But perhaps there are some ingredients which could be cancerous and distort an otherwise good reflective process from the inside.

I think that there are factors I’m pretty happy to say make it more likely we enter into the good reflective governance basin. A general focus across society on truth-seeking, on cooperation, on sincerity, and on moral action, seem like they are obviously more helpful than not. Technical tools which facilitate these things may also lay important groundwork. And exploring more what good reflective governance might look like could be of high importance. For there may come a time when some actors need to make decisions about this, and reducing the chance that they accidentally choose poorly seems wise. This strategy of shifting background variables such that the future world seems more likely to steer towards the basin is paradigmatically aiming to reach it after the Planning Horizon but before the Foresight Horizon.

In principle, one could also be interested in interventions which persist past the Foresight Horizon that aren’t to do with either of these attractors. In general I’m fairly sceptical that these should be high priorities. I think that most stable attractors which aren’t the basin of good reflective governance may end up cutting us off from the ability to properly consider things later. Perhaps there is something that could be done which locks in avoidance of certain risks without otherwise making commitments on direction. But I guess that that will typically not look better than simply working to robustly reduce those risks within the Foresight Horizon.

- ^

Actually it’s possible that some other source of intelligent life could arise. A full analysis should account for this. But as an illustrative point, and to a first approximation, I think it stands.

I love the cumulative probability graph!

Let's say the positive side of your graph has a logarithmic horizontal axis. I think there would be some probability mass that we have technological stagnation and population reductions, though the cumulative number of lives would be much larger than alive today. Then there would be some mass on maintaining something like 10 billion people for a billion years (no AI, staying on earth either due to choice or technical reasons). Then there would be another high slope region of AI doing a Dyson swarm, but either because of technical reasons or high discount rate, not going to other stars. Then there would be another high slope region where AI settles the galaxy, but again either because of technical reasons or discount rate, not going to other galaxies. Then there would be settling many galaxies. Then 30 orders of magnitude to the right, there could be another high slope region corresponding to aestivation. And there could be more intermediate states corresponding to various scales of space settlement of biological humans (and as you point out, different behaviors in different fractions of the space that can be settled). Are you are saying that if we have good reflective governance, we will have zero discount rate, so we will just do aestivation if that is optimal? Still, I think there could be technical barriers at various stages. But then would you argue that with good reflective governance we should be able to reach a high percent of the technically achievable value?

Yeah I'm arguing that with good reflective governance we should achieve a large fraction of what's accessible.

It's quite possible that that means "not quite all", e.g. maybe there are some trades so that we don't aestivate in this galaxy, but do in the rest of them; but on the aggregative view that's almost as good as aestivating everywhere.