Advanced AI could unlock an era of enlightened and competent government action. But without smart, active investment, we’ll squander that opportunity and barrel blindly into danger.

Executive summary

| See also a summary on Twitter / X. |

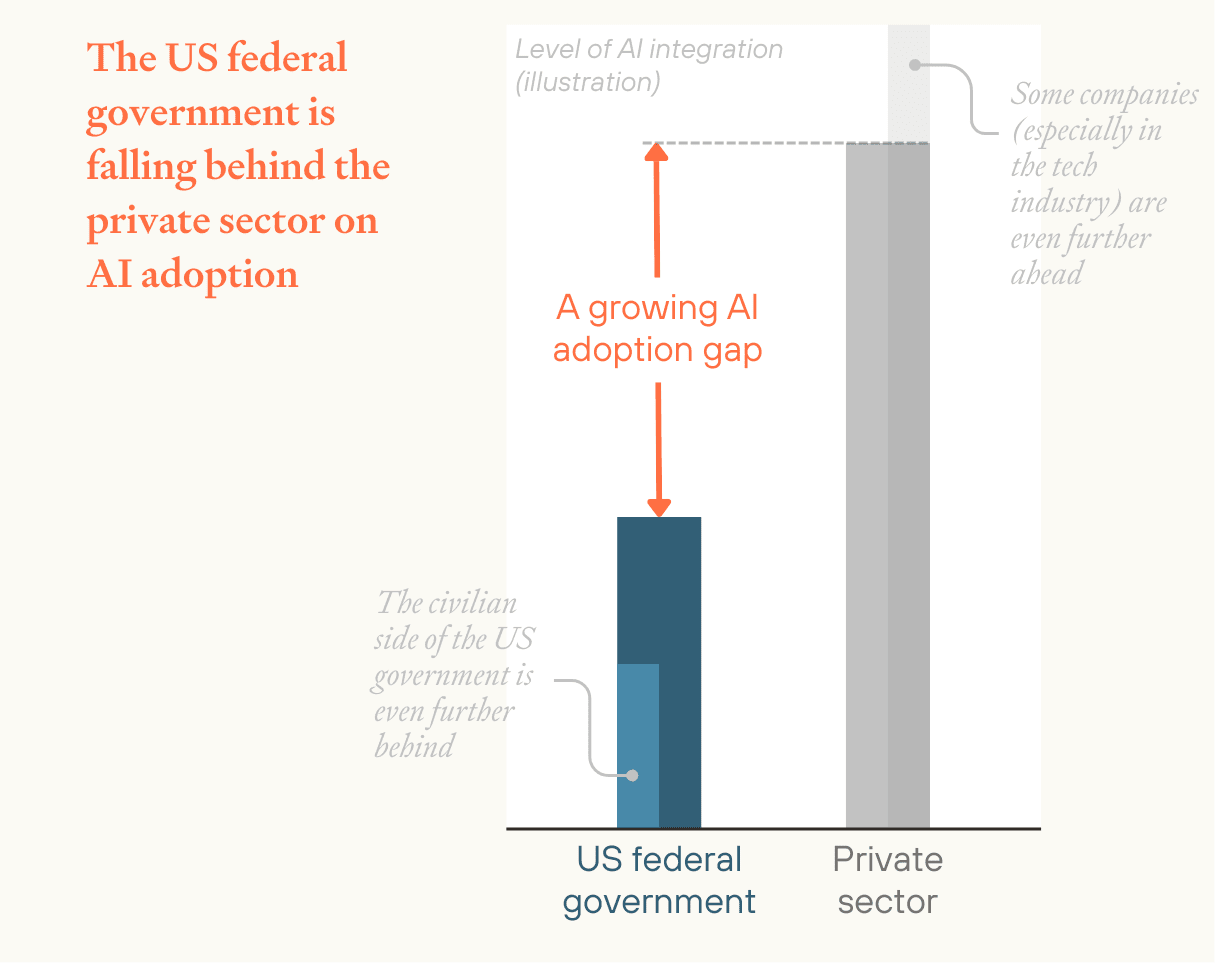

The US federal government is falling behind the private sector on AI adoption. As AI improves, a growing gap would leave the government unable to effectively respond to AI-driven existential challenges and threaten the legitimacy of its democratic institutions.

A dual imperative

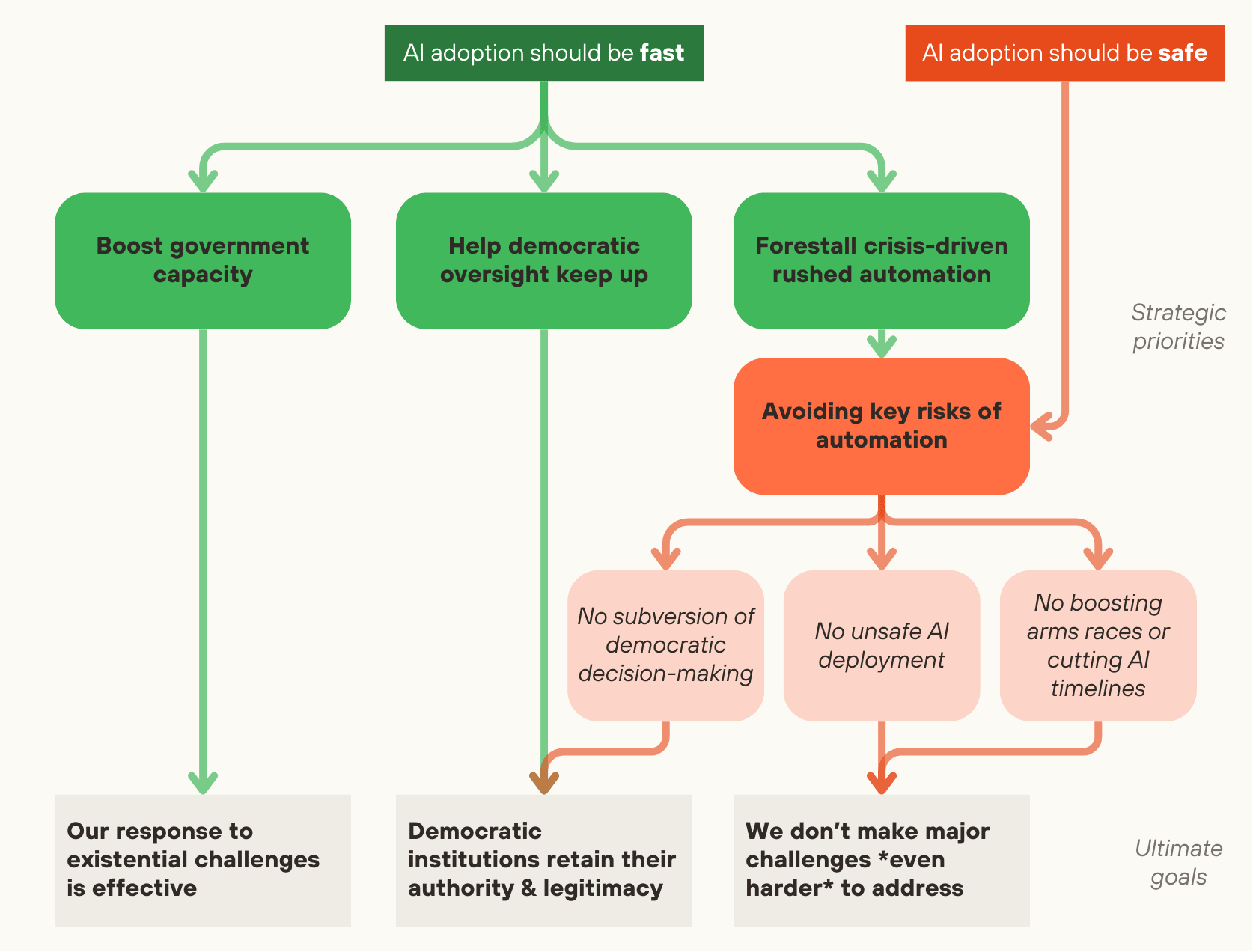

→ Government adoption of AI can’t wait. Making steady progress is critical to:

- Boost the government’s capacity to effectively respond to AI-driven existential challenges

- Help democratic oversight keep up with the technological power of other groups

- Defuse the risk of rushed AI adoption in a crisis

→ But hasty AI adoption could backfire. Without care, integration of AI could:

- Be exploited, subverting independent government action

- Lead to unsafe deployment of AI systems

- Accelerate arms races or compress safety research timelines

Summary of the recommendations

1. Work with the US federal government to help it effectively adopt AI

Simplistic “pro-security” or “pro-speed” attitudes miss the point. Both are important — and many interventions would help with both. We should:

- Invest in win-win measures that both facilitate adoption and reduce the risks involved, e.g.:

- Build technical expertise within government (invest in AI and technical talent, ensure NIST is well resourced)

- Streamline procurement processes for AI products and related tech (like cloud services)

- Modernize the government’s digital infrastructure and data management practices

- Prioritize high-leverage interventions that have strong adoption-boosting benefits with minor security costs or vice versa, e.g.:

- On the security side: investing in cyber security, pre-deployment testing of AI in high-stakes areas, and advancing research on mitigating the risks of advanced AI

- On the adoption side: helping key agencies adopt AI and ensuring that advanced AI tools will be usable in government settings

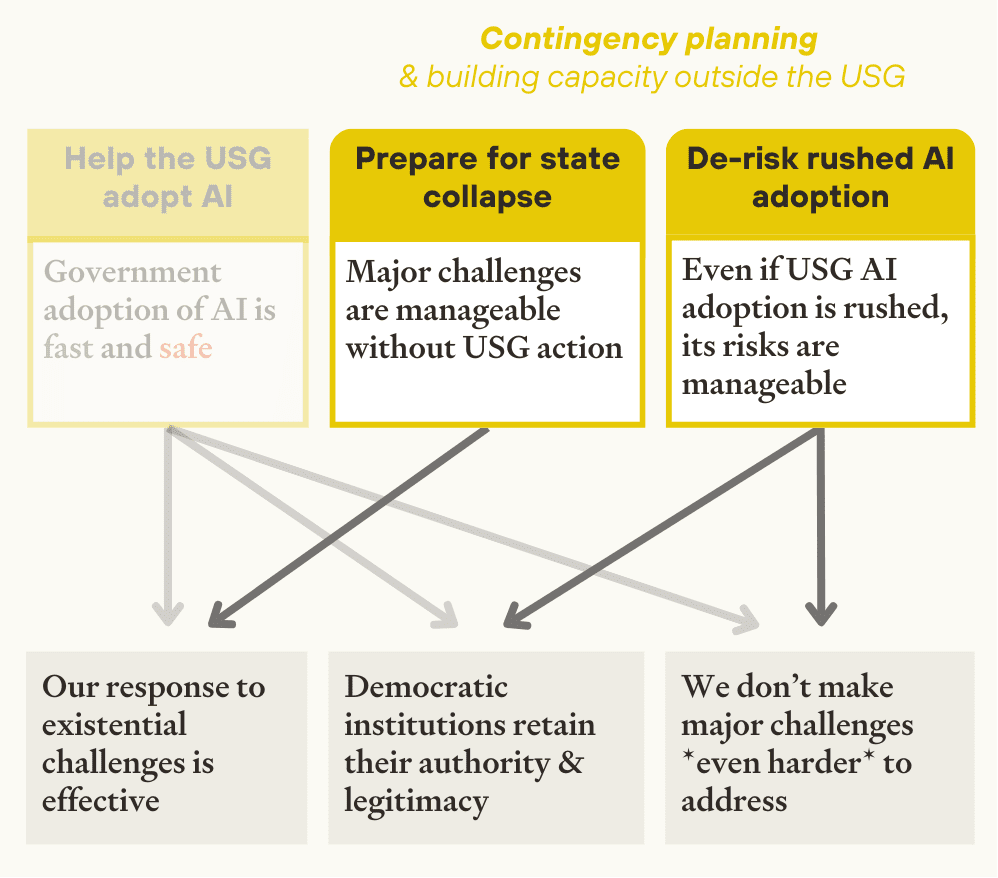

2. Develop contingency plans and build capacity outside the US federal government

Current trends suggest slow government AI adoption. This makes it important to prepare for two risky scenarios:

- State capacity collapse: the US federal government is largely ineffective or extremely low-capacity and vulnerable

- We should build backstops for this scenario, e.g. by developing private or non-US alternatives for key government functions, or working directly with AI companies on safety and voluntary governance

- Rushed, late-stage government AI adoption: after a crisis or sudden shift in priorities, the US federal government rapidly ramps up integration of advanced AI systems

- We should try to create a safety net for this scenario, e.g. by preparing “emergency teams” of AI experts who can be seconded into the government, or by identifying key pitfalls and recommending (ideally lightweight) guardrails for avoiding them

These scenarios might render a lot of current risk mitigation work irrelevant, seem worryingly probable, and will get little advance attention by default — more preparation is warranted.

What does “government adoption of AI” mean?

“AI” can refer to a wide range of things — from natural language processing to broad, generative AI systems like GPT-4. This piece focuses on frontier AI systems and their applications, including today’s large language models and more advanced tools that will become available in the coming years.

“Adoption” of AI can happen at different layers of an organization. On the “micro” level, it could mean making sure individual employees are using state-of-the-art assistants (or more specialized AI tools) to improve and speed up their task performance. Individuals’ use of AI is important and in scope, but not the sole focus of this piece; especially as AI capabilities improve, integrating AI could involve deeper or structural changes, e.g. automating institutional processes or more fundamentally reshaping how decisions are made and services are provided.

| What could deeper AI integration of AI look like in the US federal government? |

We could see:

... as well as the emergence of entirely new, AI-native government functions that, for instance, help address the problem of overlapping or convoluted governance mechanisms (what is known as “kludgeocracy”). |

This piece considers AI adoption within the US federal government quite broadly, paying somewhat more attention to the bodies involved in governing emerging technologies and to the civilian side of the government, which is adopting the technology especially slowly. Much of this discussion could also apply to other democratic nations, state governments, and even non-governmental organizations that serve the public interest.

The government is falling behind the private sector on AI adoption

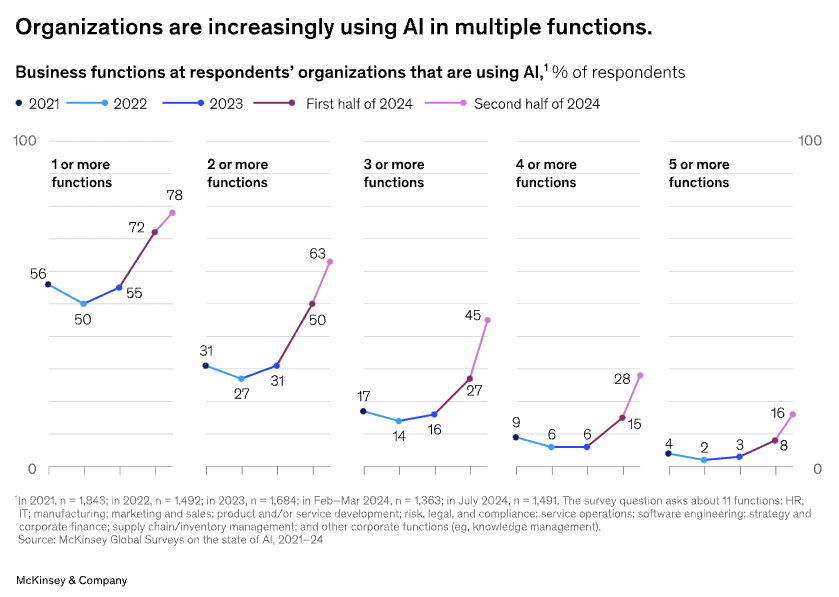

AI is starting to transform our society. State-of-the-art AI models keep getting better, and the costs of running them are plummeting. More and more companies are using AI in core business functions,[1] and organizations that leverage AI are starting to report real value and efficiency gains.[2] AI-native startups are dominating the latest cohorts of incubators like YCombinator. Platforms like Stack Overflow are seeing major decreases in traffic as users shift to AI tools.

But different groups are integrating AI at different rates, and the resulting “uplift” will be uneven. Unsurprisingly, the tech industry is among the groups in the lead.

The US federal government appears to be falling increasingly behind. Slow adoption of new technologies is the norm for governments, and current evidence suggests that AI is no different. For instance:

Private-sector job listings are four times more likely to be AI-related than public-sector job listings (and the divide is widening)[3]

In surveys, public-sector professionals report using AI less than most Americans[4]

- And various government officials have expressed the sentiment that adoption is slow

AI adoption is uneven within the government, too. Use of AI is heavily concentrated in the Department of Defense, which accounts for 70-90% of federal AI contracts, despite historically representing a minority of federal IT spending.[5]

There are some signs that US government integration of AI is ramping up:[6]

AI adoption was a priority for the Biden Administration, and the number of “AI use cases” disclosed by civilian agencies more than doubled between 2023 and 2024[7]

In January, OpenAI announced “ChatGPT Gov”, a tailored version of ChatGPT that US government agencies can deploy in their existing (Azure) cloud environments, which could help agencies manage security and other requirements[8]

The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)[9] has already used AI[10] and reportedly planned to develop a chatbot for the U.S General Services Administration (GSA) to boost staff productivity (and may replicate this effort in other agencies or lean into an “AI-first” strategy)

These efforts have had mixed success, and still leave the government behind the private sector.

Moreover, I expect this AI capacity gap to widen over time:

- Many of the original causes of slow AI adoption will persist, continuously hindering progress

The need for well organized and accessible data makes AI even harder for governments to adopt than other technologies (given sensitive information, complex and heterogenous data management policies, and an abundance of non-digitized data). That particular issue may be addressed over time, but many of the other reasons for slow adoption are not new, and will, by default, remain.[11] These include:

Scarce technical talent

Insufficient funding and convoluted procurement processes

Outdated IT infrastructure and interoperability issues, along with high security needs[12]

Poorly aligned incentives (staff and agencies are very hesitant to incur the risk of trying something new given low rewards for modernization, cost savings, or otherwise improved performance)

Burdensome legal requirements

- Meanwhile, AI and “tech-ready” companies may pull even further ahead due to persistent advantages (like early access to state-of-the-art AI models) and the adapt-or-die pressure of market forces

- Compounding effects and accelerating AI progress will widen the AI capability divide between leaders and laggards over time

- Successfully leveraging AI would translate into profits and accumulated expertise, which in turn make it easier to leverage AI in the future — a compounding effect that we’ve seen before and are seeing already with AI

- And if AI capabilities progress at a greater-than-linear speed, then lagging by a fixed amount of time will translate to a growing capability gap

- As AI capabilities improve, the private sector may be able to integrate increasingly advanced AI systems and tools that may be especially difficult to adopt in government settings

- Agentic AI systems, for instance, may be hard to deploy in government settings

It’s possible that this gap won’t widen, especially if adopting AI becomes a top national priority, if there’s a major plateau in AI progress (which could even the playing field), or if the government begins to more directly control AI development. But a growing divide between the government and the private sector seems likely.

A dual imperative for the US federal government

Government AI adoption can’t wait

There are three broad reasons for accelerating the US government’s AI adoption:

- Increasing the government’s ability to respond to existential challenges

- Maintaining the relevance of democratic institutions

- Defusing the time bomb of rushed AI adoption

1. Increasing the government’s ability to respond to existential challenges

Integrating AI could improve business-as-usual government efficiency. A significant fraction of government work is the kind that’s been productively automated or augmented with AI tools in the private sector.[13] If government agencies manage to integrate AI into their work,[14] they would likely become more responsive and efficient. Moreover, sophisticated AI-powered governance tools could address today’s regulatory failures or circumvent difficult tradeoffs.[15]

Upgrading the US government will become more important given rapid AI progress.

Normal levels of government competence may be insufficient for handling AI-driven challenges, given their technological complexity and the sheer speed at which they may emerge:

- The government may need new technical tools to verify the safety of advanced AI models, audit AI systems without compromising private information, prevent cyber-attacks, or supervise the activities of AI agents

- The speed and unpredictability of change will make it even harder to understand what’s happening and what policy responses are appropriate — and impose a higher administrative burden that may leave the government with less capacity to spare for AI-specific issues

Without better compliance tools, AI companies and AI systems might start taking increasingly consequential actions without regulators’ understanding or supervision[16]

(Of course, AI adoption isn’t the only thing that determines how effective the US government’s response is. Poor judgement of key decision-makers, polarization, selfish choices, myopic incentives, and other factors matter, too. But AI use will play an increasingly large role.)

If the US government is unable to keep up with society’s adoption of AI, the results could be catastrophic. For instance, we might see:

- Devastating global pandemics

- Without careful monitoring, AI might make it possible for non-experts to release new pandemic-capable viruses or deploy other destructive weapons

- Great power war and global instability

- Given the inherent destabilizing effects of transformative technologies like AGI, strong international coordination may be needed to prevent large-scale conflict or loss of influence of democratic countries

- Serious societal issues

- If not managed carefully, unpredictable interactions between automated systems, dramatic changes in the economy, and other change may break down social and economic institutions

- Human disempowerment by advanced AI

- Leaving AI companies to regulate themselves (by failing to pass and enforce sensible laws around AI development or failing to coordinate on AI safety internationally) increases the likelihood that uncontrollable models will be released

Capacity-building for these issues has to happen in advance — we can’t just wait for them to arise. Integrating new technology in government systems takes time. Even if procurement is streamlined, agencies would need to train their staff (and likely hire and vet new staff with appropriate expertise) and update complex and sensitive systems.[17]

2. Maintaining the relevance of democratic institutions

The military is adopting AI in large part because of the technology’s strategic relevance in shaping the international balance of power.[18] Similar dynamics might play out within the US.

For instance, groups that integrate capable AI systems may accumulate massive profits, and gain social and political power through that money — or through AI-assisted lobbying and advocacy.[19] The government will need to keep up.

Moreover, AI and technology companies could leverage their positions as providers of the technology to gain special advantages and evade oversight,[20] influence policy to advance their own agendas,[21] and (in the extreme) even subvert democracy.[22] Companies like Microsoft may already be enjoying similar dynamics at the expense of US interests.[23] Without experienced staff, the ability to oversee partnerships and evaluate alternative products, or the resources to develop and maintain systems in-house, the government may grow significantly more vulnerable to private influence.

The balance and separation of powers within the US government could also shift. If most government bodies have little AI expertise, groups that leverage the tech (e.g. by partnering with private companies) may leap ahead, broadening their reach. This doesn’t have to involve deliberate acts of subversion; it could happen simply because AI-boosted groups are able to handle more and start taking on greater responsibility. Alternatively, other government actors may unknowingly start relying on AI systems whose behavior has been shaped — perhaps in subtle, hard-to-catch ways — to advance a particular agenda.

3. Defusing the time bomb of rushed automation

Gradual adoption is significantly safer than a rapid scale-up. Agencies would have more time to build up more internal AI expertise, develop proprietary tools, invest in appropriate safeguards, iteratively test automation and AI systems, and use early efficiency gains to boost future capacity for managing AI systems.

Moving slowly today raises the risk of rushed adoption later on. Pressure to automate will probably keep increasing. And in a crisis — e.g. after a conspicuous failure, or a jump in the salience of AI adoption for the administration in power — agencies might cut corners and have less time for security measures, testing, in-house development, etc.

And background risks will increase over time. Frontier AI development will probably concentrate, leaving the government with less bargaining power. Larger technological gaps between private companies and government agencies will worsen the dynamics described above, lowering government ability to oversee private partners. The best AI systems will become more capable (and likely more agentic), making them more dangerous to deploy without robust testing and systems for managing their work. And a broadly more volatile international and economic environment may make failures especially costly. So earlier adoption seems safer.

But the need for speed shouldn’t blind us to the need for security. Steady AI adoption could backfire if it desensitizes government decision-makers to the risks of AI in government, or grows their appetite for automation past what the government can safely handle.

Government adoption of AI will need to manage important risks

Integrating AI in the government carries major risks:

- AI adoption could provide an opening for subversion of democratic processes and harm to national interests

- People with more control over government AI systems or their deployment may be able to influence what they do (possibly locking in certain behaviors in a way that’s very hard to change), use them to gain access to sensitive data (or otherwise weaken data security), or shape how and by whom the systems are used

- Increasing reliance on AI may weaken meaningful government oversight of AI companies (especially if critical areas are automated, the technology becomes more complex, and the AI market becomes concentrated)

- AI systems may be deployed unsafely, leading to catastrophic system failures

- Even before AI systems pose serious risks of takeover, AI applications might trade reliability for efficiency in areas where this isn’t appropriate

- For instance, automated processes in military contexts may escalate conflicts

- Other sources of danger include hard-to-predict interactions between automated systems, new kinds of security vulnerabilities, or “rogue” AI systems that escape human control

- Government AI integration could encourage AI race dynamics, or speed up the development of dangerous AI systems

- Other nations may interpret AI adoption by the US government as a threat, and accelerate their own adoption, potentially triggering an increasingly reckless automation race

- Increased use of AI by the US government would likely boost investment in AI development, potentially leaving less time for society to prepare for the most dangerous systems

Proper care and preparation can mitigate these risks, but we can’t eliminate them entirely.[24]

Recommendations

1. Help the US government safely adopt advanced AI

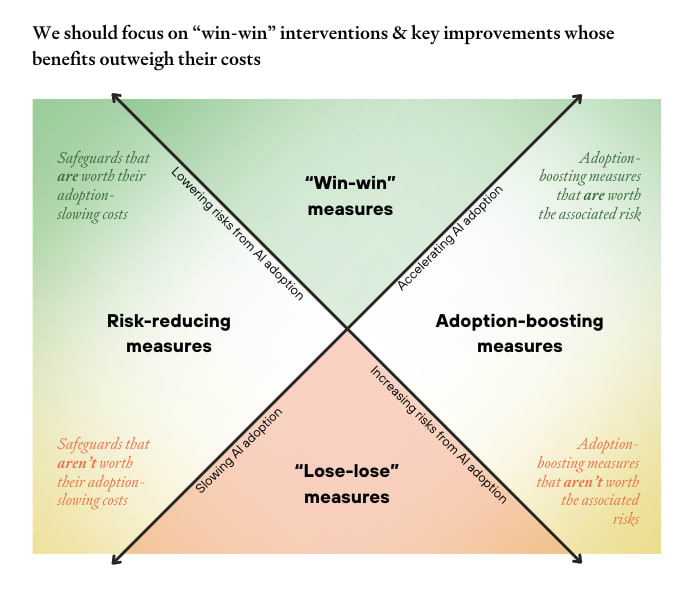

It’s natural to focus on the broad question of whether we should speed up or slow down government AI adoption. But this framing is both oversimplified and impractical — there’s no universal lever that controls the rate of adoption across the federal government.[25]

Perhaps more importantly, taking such a binary stance could lead to poor decisions. Blanket moves to accelerate adoption might override critical safety measures for negligible gains. Conversely, broad restrictions aimed at reducing risk could block valuable and relatively safe use cases.

Instead, we should do what we normally do when juggling different priorities: evaluate the merits and costs of specific interventions, looking for "win-win" opportunities and improvements whose risk-reducing benefits outweigh their adoption-inhibiting costs (and vice versa).

A) “Win-win” opportunities

Safety measures and government AI adoption don't have to be at odds. Clear policies can increase uptake — especially in risk-averse environments like government. Guidelines that are poorly tailored to reality both stifle integration of new technologies and harm compliance.[26] And reasonable precautions (and investments into transparency) can prevent backlash against the adoption of a technology. Moreover, proposals for improving both safety and speed of AI adoption will generally be the easiest to implement.

Top recommendations:

- Streamline AI procurement policies, and remove non-critical regulatory and procedural barriers to rapid AI deployment

Expedite procurement for AI and related technologies (like cloud services), for instance by fast-tracking procurement of vetted systems (and generally harmonizing processes across agencies and use cases and allowing authorization to be ported over from one agency to another),[27] developing standard terms for AI contracts, expanding flexible procurement vehicles like OTAs or TMF, and more[28]

Clarify and streamline policies around deploying AI; clearly delineate between low-risk and high-risk cases (across different use cases, AI systems, and data) to make sure policies are appropriate for the stakes involved (and avoid vague categorizations like “rights impacting”);[29] audit requirements to identify how they might be ill-suited for future advanced AI tools (including agentic systems or increased automation); avoid introducing new policies simply because AI is involved

- Invest in technical capacity in the federal government; talent is critical for deploying or building AI tools in-house, acquiring the best AI products without overpaying, and independently testing AI systems

- Hire and retain technical talent, including by raising salaries for skilled technical employees to make positions competitive with the private sector, expediting hiring (and security clearance) processes, expanding special hiring authority, recognizing skilled technical staff and providing them with growth opportunities, and strengthening the broader US AI workforce (including by keeping top talent in the US)

Nurture agencies with AI expertise, like National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST),[30] and resources like the National AI Initiative Office[31]

- Boost AI expertise among existing staff, including by incentivizing experimentation with low-risk AI use, investing in training programs that boost AI literacy across government, and developing knowledge-sharing channels

- Modernize the government’s digital infrastructure and data management practices

- Work towards secure, standardized data infrastructure across agencies, including by fixing data fragmentation and quality issues, ensuring chief data officers have the resources they need, improving data standards, and developing controls managing AI systems’ data access

- Improve or replace legacy IT systems (which could significantly cut costs), build cybersecurity capacity, address IT acquisitions issues, invest in secure/confidential computing infrastructure (and broader security improvements), and invest in interoperability of technologies deployed across different agencies — including by exploring use of AI for IT modernization

Plan for advanced AI systems, for instance by developing controlled testing environments and sandboxes or more reliable infrastructure for AI agents[32]

- Keep government decision-makers informed on AI progress and ensure advanced AI tools will be available for government use

- Track progress in capabilities and trends in adoption of AI, encourage incident-reporting, invest in forecasting AI development

- Promote development of technology that makes AI tools usable in government setting, for instance by investing in mechanisms for supporting verifiable claims about AI systems, AI evaluation as a science, privacy tools, and more

- Explore legal or other ways to avoid extreme concentration in the frontier AI market (barring exceptional concerns around security)

B) Risk-reducing interventions

If safety-oriented measures are too burdensome, they will simply be dropped by agencies when they do not have the capacity to comply — particularly in crisis situations, when they’re most needed.[33] Clumsy, gratuitous “safeguards” can actively increase the overall risk by leaving less room for other defenses or by giving the appearance of safety when the underlying problems have not actually been solved.[34]

So we should focus on the strongest, highest priority safeguards. The best safeguards will be:

- as easy to implement as possible

- scalable (or technology-agnostic), to ensure they remain in place as AI improves

- and robust to crisis scenarios

Top recommendations:

- Make it easier for agencies to comply with safety measures, especially in high-stakes areas

- Increase the resources available for safeguards, including by boosting staff capacity, funding, and compute, by giving key safeguards priority status in bureaucratic processes, and by supporting resource-sharing across agencies

Try to automate safeguards as much as possible, e.g. by building continuous verification mechanisms into the systems that get deployed[35]

- Build capacity for testing advanced AI models and automated systems that operate in high-stakes areas (and mandate such testing later on)

- Invest in in-house testing capacity, including by investing in talent (as discussed above), by ensuring the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is appropriately funded, by partnering with AI companies (and with third-party groups with AI evaluation expertise) to test earlier models, and by acquiring cloud computing and other resources needed to securely test advanced AI models

- Promote work on AI security, to decrease the risk of deploying unsafe models in high-stakes areas

- Fund research in control, interpretability, and other key areas related to AI security

- Invest in R&D projects for defensive AI tools and other beneficial technology

- More generally invest in the field of AI control and safety, including by helping the field coordinate, developing resources for public-sector researchers in the area, and more — possibly even starting a “Manhattan Project” for AI safety

- Mitigate the risk of complicating relations between the US federal government and other states or private companies that may arise via deeper government AI adoption

- Avoid over-focusing on military uses of AI and push back on perceptions of AI as “military-only” technology, and mutually beneficial use cases of AI in international contexts

- Limit the influence AI companies can exert on AI governance, for instance by exploring ways to separate incentives of government procurement and regulation decision-makers

- Other

- Develop “crisis plans” for catastrophic system failures, for instance by building viable backup systems (which could also involve making sure that qualified staff will be able to step in if automated systems fail)

- Establish clear “red lines” between appropriate and inappropriate (or unsafe) deployment of AI in government (including requirements about certain forms of information-sharing, ensure information about inappropriate deployment would be shared (e.g. via whistleblowing or secure incident-reporting mechanisms), and agree on what the responses should be if those lines are crossed

C) Adoption-accelerating interventions

Loudly advocating for increased government use of AI may prompt superficial investment in “AI” tools that are weak or not actually helpful, or encourage decision-makers to blind themselves to security concerns. Instead, we should:

- Try to accelerate AI adoption in key agencies

- On the civilian side this includes:

- DOGE, OMB, and other agencies that coordinate government resources

- NIST, CISA, and BIS, which are all heavily involved in (international) AI security work

- National Security Council (for national security decision-making) and National Economic Council (for tracking economic matters)

- Energy (National Labs), Treasury, the Federal Reserve, and other agencies involved in managing key infrastructure and critical for managing and tracking AI diffusion

- State, especially for intelligence analyses, negotiations, better enforcement of treaties, etc.

- On the civilian side this includes:

- And focus on scalable, future-oriented use cases

The best ways to do this — besides the “win-win” opportunities above — might involve:

- Informing, planning, and strategic work

- Ensure key decision-makers are informed about current and forecasted AI capabilities (and the challenges they may need to deal with)

- Audit key agencies’ needs and try to identify potential core use cases, including in crisis scenarios, likely bottlenecks to adoption, and promising next steps

- Ensuring that advanced AI tools will be usable in government settings, and developing custom tools for government agencies

- Invest in making advanced AI products usable in government settings, including by going through authorization processes, investing in “security by design” and other properties relevant for high-stakes contexts, and mitigating other barriers to adoption

- Try to speed up the development of new AI applications for government buyers and contexts

- Getting key agencies “AI-ready”

- As discussed above, ensure they have necessary resources (funding, talent, and compute), as well as strong digital systems and data management practices

- Get them started; work with them to decompose core responsibilities and define success criteria, investing in robustness checks to avoid issues like adversarial specification gaming, help them evaluate or develop and iterate on early AI tools

- Ensure that they will have access to frontier AI systems in the future, especially in crises

2. Contingency planning for slow government AI adoption

Besides trying to steer government adoption of AI, we should probably prepare for scenarios where government adoption remains very slow.

A) State collapse: a largely ineffective or vulnerable US government

If the US government never ramps up AI adoption, it may be unable to properly respond to existential challenges. At least in AI safety,[36] it might makes sense to invest more heavily in:

Proposals for AI governance that do not rely on US federal government action[37]

Build independent third-party AI auditors and evaluators that can substitute for the government (e.g. by being authorized to operate on its behalf or operate entirely without US government support)

Explore private AI governance, or what more AI-ready state governments can do

Create AI governance institutions in countries like the Netherlands or the UK, or multilateral governance institutions

- Technical rather than policy-based interventions for preparing for looming challenges

- Map out scenarios in which AI safety regulation is ineffective and explore potential strategies, e.g. by trying to solve resulting cooperation problems

- Work directly with AI companies to develop and implement internal safety protocols and governance systems, and help companies coordinate on those priorities

- Generally work on technical solutions (e.g. paying the “alignment tax” or differentially promoting defensive technologies)

B) Rushed AI adoption

Hasty integration of AI in the US government would go better if we prepared for it in advance (even if that preparation happens outside the federal government).

Many of the interventions that could help to avoid this situation would also help with de-risking rushed automation. Besides those, it could help to:

- Build emergency AI capacity outside of the government

- Coordinate with AI experts to create “standby” response teams that can be quickly seconded into government roles (e.g. via the Intergovernmental Personnel Act)

- Develop standardized protocols for rapid but as-safe-as-possible AI integration (including toolkits on improving infrastructure)

- Invest in compute and energy resources

- Develop tools that the US federal government would be able to rapidly deploy

- Create monitoring and testing systems that satisfy the needs of relevant agencies and can be deployed very quickly

- Try to build provably secure or guaranteed-safe tools for government officials, and custom tools for specific high-priority use cases (e.g. chip verification mechanisms)

- Other

- Develop training programs for government officials

- Analyze potential high-stakes failure modes

- Continuously test state-of-the-art AI tools and systems — and generally try to vet AI companies — to help inform (rushed) decision-makers in procurement processes

Conclusion

AI is a growing force. In the near future, it’s likely to massively accelerate the pace of change and trigger existentially relevant challenges that the US government will need to respond to. I’m worried that the US government’s adoption of AI isn’t on track to keep up with its crucial role.

Improving government adoption seems like a neglected lever for reducing existential risks.

Acknowledgements

I'm very grateful to Nikhil Mulani, Max Dalton, Rose Hadshar, Owen Cotton-Barratt, Fin Moorhouse, and others for conversations and comments on earlier drafts.

- ^

Surveys suggest that AI is rapidly diffusing into workplaces; in 2023-2024, the annualized growth rate in uptake was around 70-140%.

- ^

Field tests show significant boosts to performance. For instance, a recent experiment showed that R&D professionals working with AI “teammates” performed as well as two-person teams that didn’t use AI. (The size of the boost seems to vary by type of task, employee skills, and more.)

Real-world data is limited, but some studies that attempt to measure productivity gains have been compiled by Epoch.

- ^

An analysis of job listings shows that from 2017 to 2023, the percent of all job postings represented by AI jobs grew from 0.5% to 2% in the private sector but remained fairly flat in the public sector, at around 0.25%. (The authors suggest that the difference in pay might be an important factor in the public sector’s inability to attract and retain AI talent; average posted salaries are around 50% higher in the private sector.)

- ^

A late-2024 AWS survey of “public-sector IT decision-makers” (839 respondents across the federal, education, nonprofit and healthcare sector) found that only 12% reported that their company has already adopted generative AI. (Apparently 30% expect this to happen within the next 2 years. Two thirds have found it difficult for their organization to adopt generative AI; current and future barriers that were cited include lack of clarity on how it might be useful, concern about the cost of integrating AI with legacy systems, concern about public trust, and concern about data security and privacy.) The general US public, meanwhile, appears to use AI for work fairly frequently; a NBER report found that in a nationally representative US survey, over 28% of adults use generative AI for work. And among “knowledge workers” 52% reported using AI weekly.

Comparing results from different surveys is difficult, but other data-points seem to confirm the general trend. See e.g. another late-2024 survey of public-sector AI use from the Hoover Institution, and a review of general-public surveys here.

- ^

A report from Brookings found that over the last few years, most of the growth in the number (and total value) of federal AI-related contracts was concentrated in the Department of Defense (DOD). By August 2023, federal agencies had committed to a total of $675 million in contracts (which might be paid out over the course of several years), of which 82% is from DOD contracts — leaving $118 million for all other agencies. This trend was even more extreme among new contracts; in FY2023, 88-96% of federal AI contracts were due to the DOD.

It’s not just contracts. In surveys, DOD staff report more use of AI. And a Stanford white paper noted that while agencies requested an average of $270K to support each AI office in their 2025 congressional budget justifications, the DOD proposed a budget of $435 M.

Meanwhile, the DOD has historically accounted for less than half of federal IT spending — generally between 40% - 50%, although data wasn’t provided in recent years. (The DOD tends to dominate federal contract spending, driven primarily by weapons systems.)

- ^

Adoption is increasing outside the US too. In the UK, Anthropic is partnering with the government to explore how Claude could enhance public services. The UK government has also announced an AI Opportunities Action Plan, which, among other things, proposes building a UK AI cluster.

- ^

It’s worth keeping in mind that some of these use cases are just being tested — and many are not “sophisticated.” When canvassing agency use of AI in 2020, Stanford computer scientists evaluated the techniques deployed in each use case. For many, there was insufficient information provided. Of the rest, only around 30% were rated as “high in sophistication.” (“To illustrate the scale used, we considered: (a) logistic regression using structured data to be of lower sophistication; (b) a random forest with attention to hyperparameter tuning to be of medium sophistication; and (c) use of deep learning to develop “concept questioning” of the patent examination manual to be of higher sophistication.”)

- ^

OpenAI is also working toward higher levels of FedRAMP accreditation for ChatGPT Enterprise, but that process tends to take a long time. It’s also worth noting, however, that OpenAI is closely partnered with Microsoft, which might streamline integration given Microsoft’s dominance in US government IT.

- ^

Some have suggested that DOGE could be a good opportunity for boosting the US government’s technical and AI capacity. If executed poorly, though, DOGE could have the opposite effect — e.g. by reducing already limited critical AI expertise in the federal government (see also commentary from Alex Stapp) or by cutting the funding agencies have for AI adoption

- ^

Note that there are a number of concerns (related to data security and other issues) about how DOGE’s use of AI

- ^

In a review of the AI “Compliance Plans” agencies had published (as of October 2024), authors found five common themes across different agencies’ discussions of the barriers they were encountering for AI innovation and internal governance. These were:

Funding (especially for “AI governance”)

Shortage of AI talent and expertise

Challenges with access to computing infrastructure

“Difficulties in accessing and validating data sources for AI models, alongside data privacy and security concerns”

“Regulatory ambiguity”

- ^

As one concrete example, the GSA reportedly recently sought to deploy the popular Cursor code editor, but pivoted to a different assistant because Cursor isn’t planning to achieve FedRAMP authorization (a lengthy and fairly costly process) in the near future.

- ^

A report on “An Efficiency Agenda for the Executive Branch” includes relevant discussion: “An Accenture analysis estimated that 39 percent of working hours for the public service sector have a ‘higher potential for automation’ or ‘augmentation.’ [...] [A study on jobs more exposed to AI] found 86 ‘fully exposed’ job categories in total, largely within the realm of administrative and knowledge labor. These occupational categories have substantial overlap with the jobs and task sets commonly seen within the federal workforce, suggesting that the federal bureaucracy is itself highly exposed to AI-enabled labor savings.”

For more on which areas might be automated earlier, see “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality”

- ^

See more on specific use cases in Government by Algorithm: Artificial Intelligence in Federal Administrative Agencies, which distinguishes between policy setting/research/monitoring, enforcement, delivering services, and internal management. As a concrete example, the Treasury Department is already using AI to monitor and enforce corporate compliance.

- ^

For instance, structured transparency technologies could facilitate measures that today would require impractical violations of privacy (e.g. monitoring), or conversely reduce the privacy costs of current security measures.

- ^

Analogous things have arguably happened before; the financial crisis of 2008 is at least partly the result of increasing complexity in the financial sector, without a sufficient increase in monitoring and understanding from regulators.

- ^

Recently DOGE wanted to build and use a tool that would help it navigate the GSA’s main portal. Wired reported that, while given today’s technology this might seem like a simple project to people unfamiliar with the GSA’s systems, it’s more realistic to think of it as a multi-year endeavor: “every database would need to be mapped, its columns and metadata described and categorized, ensuring the system understood what data lived where. None of this would happen automatically. It would be a manual, painstaking process.” (A simpler version of this tool, the GSAi, began development during the Biden administration; it was announced in March 2025.)

- ^

See for instance the DOD’s “AI Adoption Strategy,” which stresses goals like “ensure U.S. warfighters maintain decision superiority on the battlefield for years to come” and “competitive advantage in fielding the emerging technology.”

- ^

For instance, it seems that Standard Oil used its massive economic and political leverage to resist regulation for many years.

- ^

For instance, the government may be unable to verify AI companies’ claims about their testing practices or the safety of their AI models.

- ^

- ^

See a forthcoming paper from Tom Davidson, Lukas Finnveden and Rose Hadshar: “AI-Enabled Coups: how a small group could use AI to seize power”

- ^

Microsoft holds around 85% of the share in US government office productivity software, and appears uniquely insulated from government accountability. (Network effects make this very difficult to change.)

It appears that the US government’s interests have already been harmed by this; Microsoft’s systems have been repeatedly hacked by the Chinese government and other actors, jeopardizing the security of sensitive data and systems across dozens of agencies. (It’s not clear if Microsoft’s approach to security is improving.)

- ^

Note: if we did manage to eliminate the risks from poorly implemented AI adoption, automation could enable persistent and very harmful government decisions. This is out of scope here.

- ^

Still, I overall expect that near-future AI adoption will be slower than the “ideal” pace that would minimize the total risks involved.

- ^

This phenomenon is pretty widespread, and we’re already seeing it with AI uses. “Shadow AI use” — employee use of AI without managers’ knowledge — is emerging in the private sector at least. And regulatory ambiguity is already cited as a barrier for compliance with OMB directives. This response to the OMB also discusses related issues.

- ^

See:

NAIAC’s recent recommendation: establishing an AI model evaluation, testing, and assessment framework to help address the issue of “considerable variation in federal agency capacity to integrate modern AI systems without significant upgrades or overhauls.”

Google’s response to the OSTP’s AI Action Plan request, which emphasizes the need to allow authorization to be ported from one agency to another

GAO’s 2024 analysis of federal software licenses, which found a number of issues with tracking the usage and inventory

- ^

Other promising directions here have been discussed in various responses to the OSTP’s AI Action Plan Request. These include relevant recommendations from Anthropic:

Tasking the OMB to “rapidly address resource constraints, procurement limitations, and programmatic obstacles to federal AI adoption, incorporating provisions for substantial AI acquisitions in the President’s Budget”

Leveraging “existing frameworks to enhance federal procurement for national security purposes, particularly the directives in the October 2024 National Security Memorandum (NSM) on Artificial Intelligence and the accompanying Framework to Advance AI Governance and Risk Management in National Security”

Creating “a joint working group between the Department of Defense and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to develop recommendations for the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council (FARC) on accelerating procurement processes for AI systems while maintaining rigorous security and reliability standards. The FARC should then consider appropriate amendments to the Federal Acquisition Regulation based on these recommendations to create a procurement environment that balances innovation with responsible governance.”

- ^

See for instance concerns about use of “rights impacting” and “safety impacting” in OMB’s guidance

- ^

which houses AISI, the AI Risk Management Framework, and more

- ^

See a bit more about resourcing the NAIIO in NAIAC’s recent recommendation to President Trump

- ^

Government by Algorithm: Artificial Intelligence in Federal Administrative Agencies discusses sandboxes in Part III.

- ^

We’re already seeing this with government AI adoption. Reviews of compliance with OMB directives and AI-oriented executive orders have found very uneven results.

The capacity of internal supervisory bodies that enforce compliance with safety-oriented policies should also be taken into account. See for instance the “emerging crisis in mass adjudication” discussed here.

- ^

A paper that analyzed policies requiring human oversight of government algorithms found that staff were often unable to provide the required oversight. It argues that as a result, “human oversight policies legitimize government uses of faulty and controversial algorithms without addressing the fundamental issues with these tools.”

- ^

For more in this vein, see a discussion of automated monitoring and accountability in “Government by Algorithm” (which in turn references this paper on a technological toolkit for “Accountable Algorithms”)

- ^

We should also explore how we can better prepare for other existential challenges we might be facing, like risks from engineered bioweapons.

- ^

It might also make sense to explore whether other government responsibilities can be done outside government (either now or in crisis situations).

I've been thinking a lot about this broad topic and am very sympathetic. Happy to see it getting more discussion.

I think this post correctly flags how difficult it is to get the government to change.

At the same time, I imagine there might be some very clever strategies to get a lot of the benefits of AI without many of the normal costs of integration.

For example:

Basically, I think some level of optimism is warranted, and would suggest more research into that area.

(This is all very similar to previous thinking on how forecasting can be useful to the government.)