Note: Cross-posted from my blog. There is probably not much new here for long-time members of the EA community, some of whom have been giving 10%+ of their income for over a decade. However, I thought it might be interesting for newer EA Forum readers, and for folks who are more left-wing/progressive than average (like me), to see what arguments are compelling to someone of that worldview.

In November 2022, I took the Giving What We Can pledge to give away 10% of my pre-tax income, to the most effective charities and opportunities, for the rest of my life. I’m very proud of taking the pledge, and feel great about finishing my first full year! I wanted to share some thoughts on how it’s been for me, as well as some concrete places I donated to.

Broadly, I feel like I’ve been committed to doing the most good (whatever that means) for several years now, but it took some time for me to get going with my donations. One big factor is that I haven’t been earning too much, especially when I was working full-time with Animal Rebellion/Extinction Rebellion, where people used to get paid between £400-1000 per month. Otherwise, I thought it would be a significant financial burden, even when my salary increased, that would make it difficult for me to build a financial safety net. But primarily, it’s a reasonably big commitment, so I think taking some time to stew on it can be useful.

Despite this, I’ve been surprised by how quickly the Giving What We Can (GWWC) pledge has become a part of my identity. Now, I’m so happy that I’ve pledged, and feel amazing that I’m able to support great projects to improve the world (you can tell because I’m already preaching about it – sorry not sorry).

Importantly, I don’t think donating is the only way for people to improve the world, and not necessarily the most impactful. But, I don’t see it as an either/or, but rather a both/and. Simply, I don’t think the decision is whether to dedicate your career to highly impactful work OR dedicate your free time (or career) to political activism OR donate some proportion of your income to effective projects. Rather, I think one can both pursue a high-impact career and give a lot, as donating often gives you the ability to have a huge impact with relatively little time investment. Tangibly, I’ve probably spent between 5-10 hours to donate around £3,000 this year, which I think will have a lot of positive impact with a relatively small time investment on my side (this was helped partially with the use of expert funds and my prior knowledge in a given area, but more on that later).

However, I want to speak about some of the key points that convinced me to give 10% of my income for the rest of my life, namely:

- I am better off than 98% of the world, for no great reason besides that I grew up in a wealthy country, and it is a huge travesty if I don’t use some percentage of this luck to help others.

- Donations can have very meaningful impacts on the issues I care about, often far more than other lifestyle choices I might be already making.

- I think the world would be a much better place if everyone was committed to giving some of their income/wealth, and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t start with me.

(If you just want to see where I donated to in 2023, skip to the bottom).

Why I decided to take the pledge

Most people reading this are in the top 5% of wealth globally, and we should do something about it

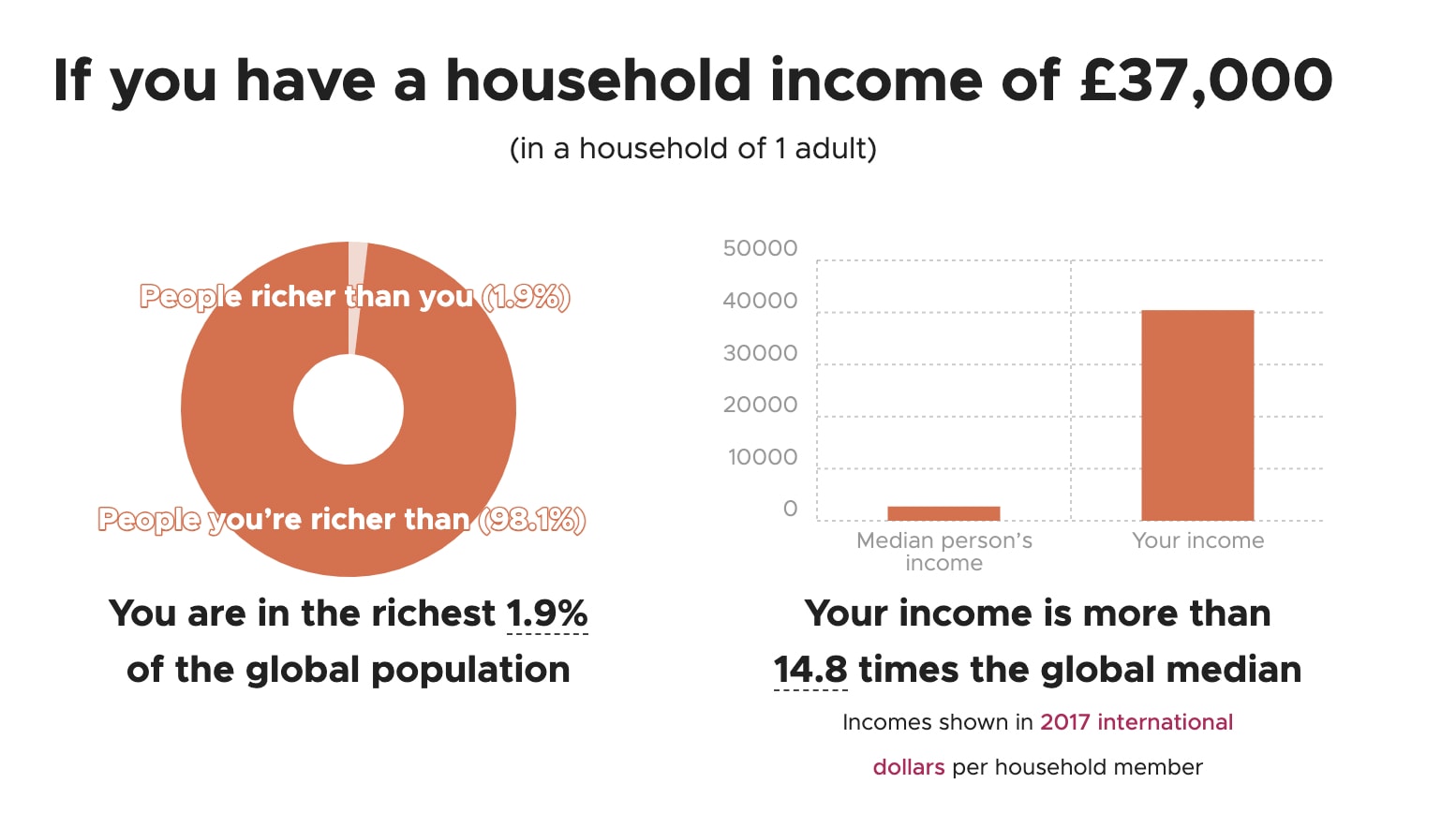

As someone who has been fairly engaged in progressive political activism, I often hear lots of comments attributing some key problems in the world, whether it’s climate change, inequality or poverty, to the richest 1%. However, I think most people in wealthy countries underestimate how close they are to being in the top 1% of rich people globally. Specifically, my current annual earnings (approx. £48k, post-tax of £37k) puts me in the richest 2% globally. I would encourage folks to do this exercise for themselves, with the useful How Rich Am I calculator.

For me to have an income which is almost 15x the median income seems absolutely bonkers, not to mention unjust. And I don’t think it’s just me. The median post-tax income in the UK is around £27,000, which puts the average person in the UK in the top 5% of global income, with an income that is around 11x the global median.

One of the most meaningful essays I’ve ever read was Famine, Affluence and Morality by Peter Singer. It talks, bluntly, about how people in Sub-Saharan Africa and other poor parts of the world are living, and dying, in extreme poverty, whilst most of us in the Global North spend our money on frivolous things. The classic thought experiment involves a child drowning in a pond: If we directly see a child drowning in a pond, would we run in to save them? The answer (hopefully) is yes – we might sacrifice our expensive iPhone, clothes or other items, but the life of a child is worth more than this. The reality is, we are faced with this decision every day, when purchasing things in our day-to-day life and not giving away much, if any, to worthy causes.

One way I’ve found to cope with the demandingness of this argument is to simply commit to giving 10% of my income, as otherwise it can feel like you should live the most ascetic lifestyle possible, and give away everything else to someone more in need, which was certainly weighing on my mind in unhealthy (but probably important) ways.

Important note: I talk a lot about giving to humans above, as this is what most people think of when it comes to charity, but I strongly believe we should extend our charitable considerations to other sentient beings, particularly farmed animals who experienced terrible lives full of suffering in factory farms and industrial agriculture.

If you want to learn more about how the 80+ billion land animals that are farmed each year are often treated, and the impacts it has on the environment/climate change, I would recommend reading this explainer, this short story or this (graphic but important) documentary. Additionally, the food system is responsible for approximately 26% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with most of that being from animal products, so a global shift from animal protein to plant proteins has important environmental and health benefits.

Donating is one of the most impactful personal lifestyle choices you can make

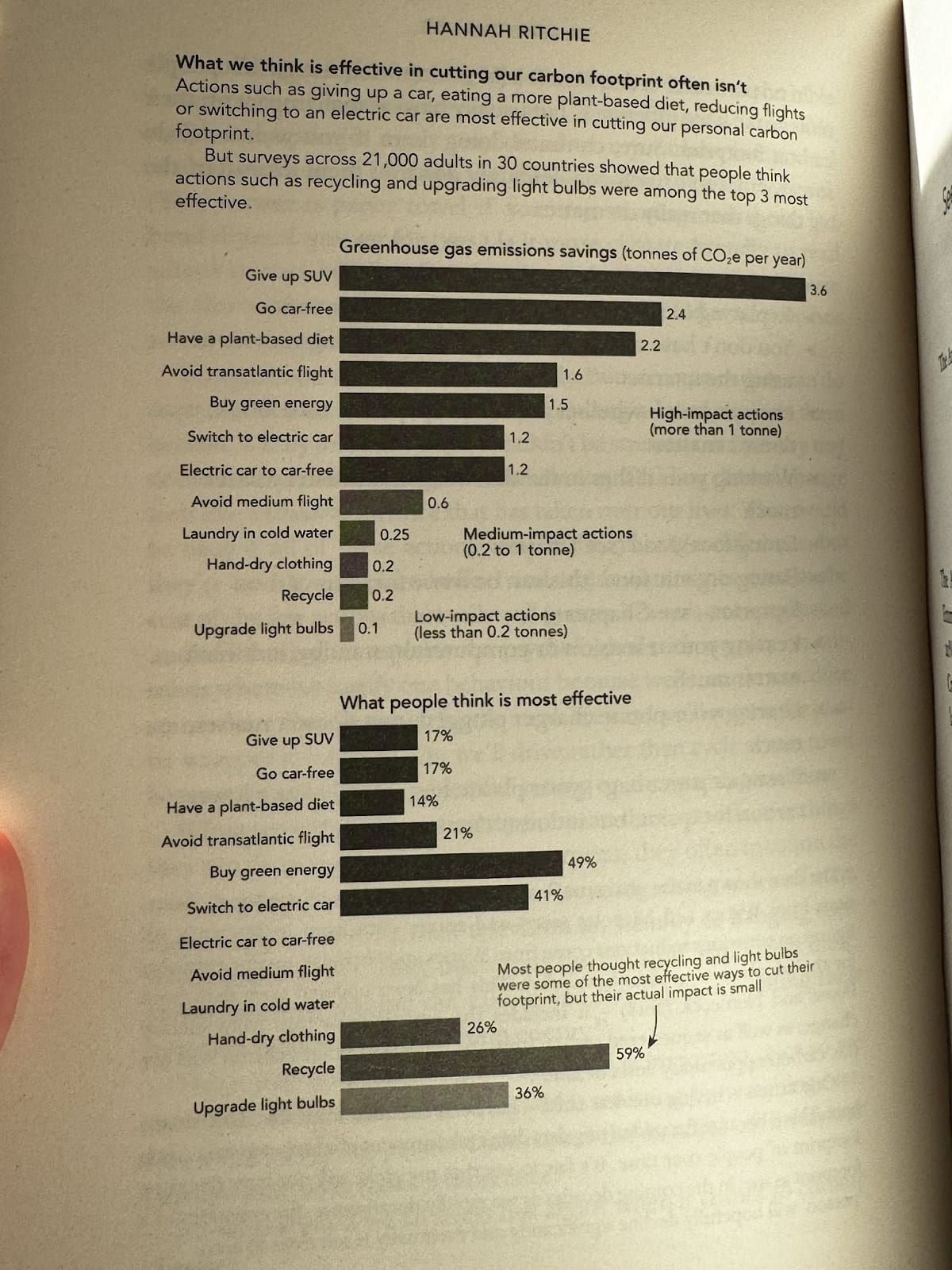

The dominant thinking within the modern progressive climate movement (at least, the bits I’m involved with) emphasises the importance of systemic change over individual lifestyle changes. I broadly agree with this, and I think many people (especially mainstream politicians and “influencers”) over-emphasise the importance of changing lifestyle habits to help the climate, whether it’s recycling, reusable bags or skipping plastic cutlery. An example of this is shown below, stolen from Hannah Ritchie’s new book (and a tweet of some of her graphs here).

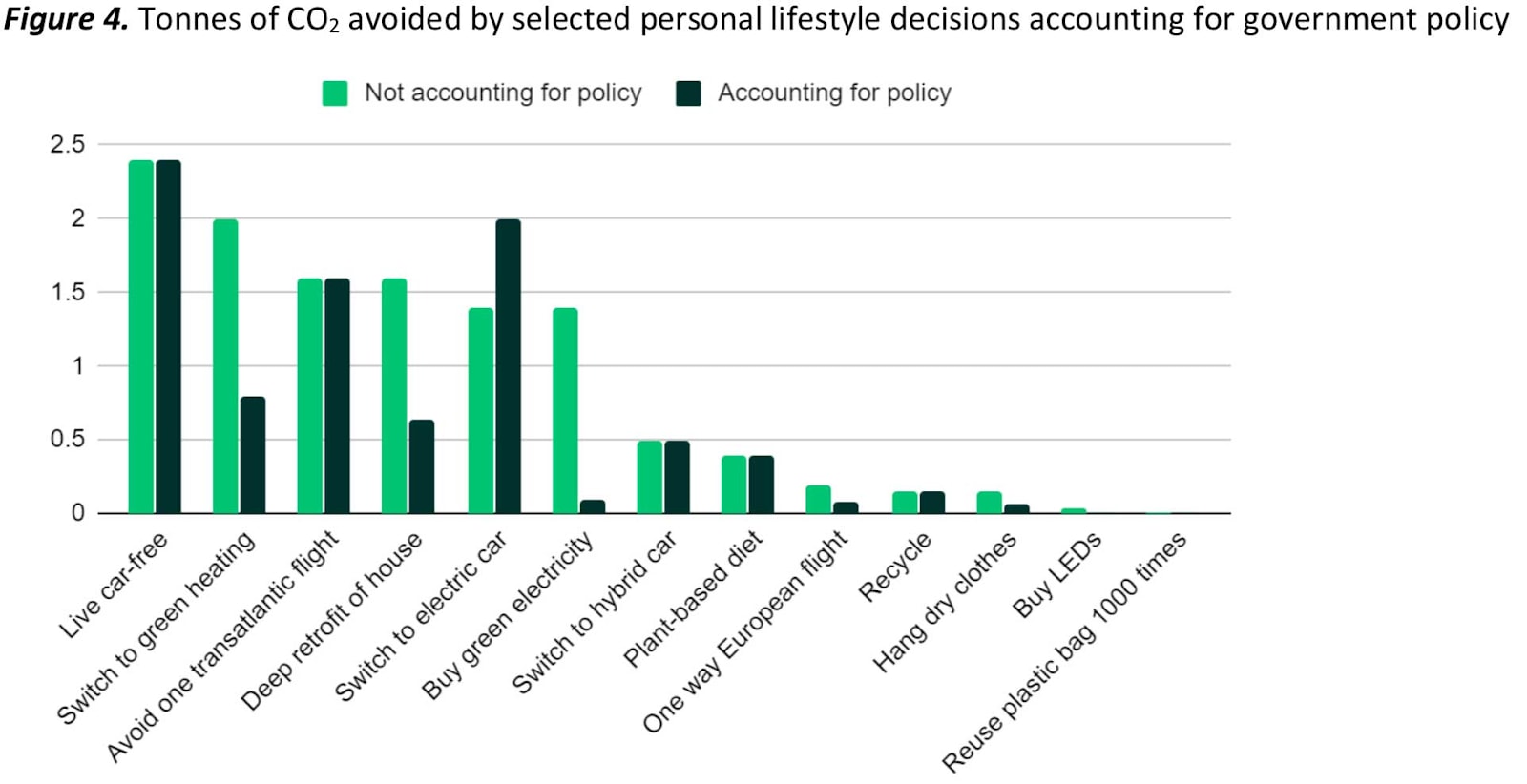

Despite this, I still think some individual lifestyle choices matter enough to be worth taking, both for their direct impact on emissions and the value of them becoming a widespread norm. Specifically, I think this is true for not eating animal products, minimising long-haul flights (especially for pleasure) and avoiding internal combustion engine cars. In addition to Hannah’s research above, there is some useful research from Founders Pledge that evaluates the climate impact of these various lifestyle changes, which you can see below (I have cropped out having a child, which makes the graph less helpful to look at).

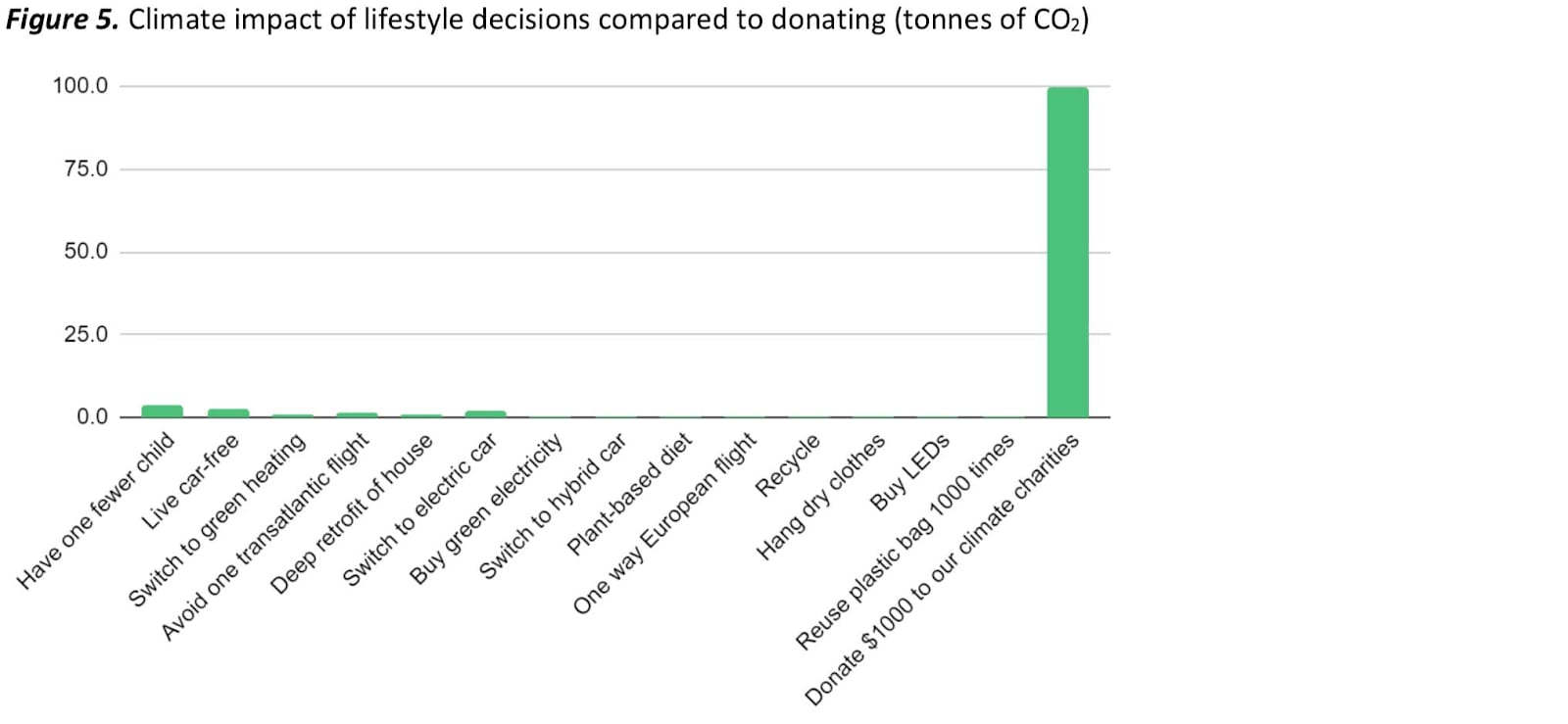

Interestingly, Founders Pledge also evaluates the impact of climate donations on the same axis, and the results are pretty surprising. The emissions reduction of donating $1000 to a high-impact (according to them) climate nonprofit dwarfs the other lifestyle choices, by around 5-1000x. Obviously, not everyone is going to donate $1,000 but the point still stands for a $100 donation: An $100 donation to effective climate charities is estimated to be around 67x better than recycling, 7x better than switching to green electricity and 6x better than thoroughly insulating your house in terms of carbon emissions averted.

Founders Pledge includes the necessary caveats on this page, specifically around the uncertainty in the exact climate impact of donating to climate nonprofits that focus on policy advocacy. However, I’ve had a look at the underlying report and it seems relatively reasonable, and they are in a similar ballpark to estimates by Giving Green, a climate charity evaluator. Even if you apply a reasonably big discount to Founders Pledge’s number, I think the point stands: donating to high-impact organisations is one of the most significant ways you can have an impact as an individual.

I think the same holds true across other social issues as well, for example:

- Giving $5,000 to the most effective global health charities will likely save someone’s life (in expectation). I can’t think of many other ways that the average person in a rich country could save someone’s life, each year.

- Corporate campaigns against large companies that confine chickens in cruel conditions could avert about 41 years of chicken suffering per dollar spent. This number seems absurdly high, and the campaigns are likely much less cost-effective now, but to even think you can avert one year of a chicken suffering in a cage for $1 seems like such an obvious thing to do.

I think what’s doing a lot of work in Founders Pledge’s calculations, and my writing above, is that this is the estimated impact if you’re giving to “effective” charities. There is a huge amount of disagreement on what that actually means, and it requires various empirical and values-based judgements to arrive at what you think is an effective charity. I’ve covered some of these disagreements in my previous post on Different approaches to doing good, so won’t do so again for the sake of brevity. In short, my recommendations (for most people who aren’t thinking or working on this stuff full-time) are to go with charities identified by a rigorous and impact-focused charity evaluator, such as GiveWell for global health, Giving Green for climate or Animal Charity Evaluators for animal advocacy.

Again, this isn’t to say one shouldn’t do any of the above lifestyle choices, or other important things such as political activism or organising. Rather, it’s to highlight how much impact we can have if we simply add donations to our idea of important personal actions.

The world would be a much better place if everyone gave away more

This principle is fairly simple, but I believe that the world would be a much better place if everyone were just a bit more generous. Sure, we can say that the most elite 0.1% who own most of global wealth should be the ones to act first, but that’s not actually helping anyone. We can’t simply will them into doing so, and it doesn’t seem like our political system is going to do anything serious about it either. If anything, I think this is a lazy excuse by (often very progressive) people who don’t want to take meaningful action with their own wealth and want some justification for not doing so. I find this particularly frustrating as it often comes from people who are relatively privileged and in the top 5% of global rich people, putting them closer to billionaires in terms of wealth percentiles than the poorest 50% of the world who live on less than $6.85 per day.

If you’re interested in reading someone else’s take on why the GWWC pledge is great, I would recommend this piece by Vox. You can learn more about it on the GWWC website.

Where I gave to in 2023

Now, time for the nitty gritty stuff. Here is where I donated in 2023, both within my pledged donations and outside of them, as well as my reasoning for doing so. From my largest donations to my smallest:

- Yet to be decided / Waiting for a good opportunity – £2,000

- This seems slightly like a cop-out after moralising about the importance of donations but the main driver is that I now have a new job, where I manage a philanthropic grantmaking portfolio at a family office (Mobius) focused on positively transforming the food system to reduce animal suffering and environmental harms. As such, I get to play a meaningful role in where our donations are allocated, and obviously these amounts are much greater than my personal giving. This means I want to think extra hard about where to spend my personal donations, given I can support great nonprofits I think are doing highly impactful work through this new role. This likely means I will try to donate to things my employer can’t or won’t, which might include political donations, grassroots activism, or simply niche projects that I feel could be impactful but others are less excited about (suggestions welcome!).

- Political donation – £1,500

- Following on from the above, someone I know was fundraising to run to be an MP in the UK, and I wanted to support his campaign as I think he would do a great job on a variety of issues. I think political donations are one of the few ways where individual donors can have a big impact, as foundations and major donors often can’t or won’t get too involved here. This was my first political donation and in some ways, it feels a bit icky, but I stand by this as a neglected and important way for individuals to have an impact on our political system.

- Animal Charity Evaluators (ACE) Recommended Charity Fund - £452

- ACE conducts research and recommends the most impactful charities that help animals each year (see their 2023 recommendations). I wanted to donate to their matching challenge for this end-of-year donation campaign where my donation would get doubled (although I am still quite unclear if the donation was a counterfactual match). Overall, I think ACE has a very important role to play in the animal advocacy movement, and I’m excited about their recent direction, which is focused on attracting more donations towards farmed animals from people who who support generic animal welfare charities (e.g. by showing how farmed animals outnumber cats and dogs by upwards of 100,000x so it makes sense to focus your donations there if you want to help the most animals). Conflict of interest: my partner recently started working there!

- Animal Advocates International – £235

- For Animal Advocates International and Animal Welfare League below, this was the product of an interesting exercise that I did with some friends from the Charity Entrepreneurship Incubation Program. Long story short, around 6 of us (who all work in the animal advocacy movement in some way) wanted to donate to some animal advocacy nonprofits. We wanted to pool our money together as we’re all relatively small donors, to lessen the burden of all of us doing separate evaluations of charities, and able to contribute a more meaningful amount of an organisation’s budget.

- Using this approach, we landed on two charities, one of which is Animal Advocates International. Animal Advocates International works in Zimbabwe to support caged-egg farmers in transitioning to cage-free systems, where the suffering inflicted on hens is much less.

- The Humane League (THL) UK – £220

- I took part in a triathlon in September 2023 where I fundraised for two charities, The Humane League UK and Hamlin Fistula UK. I wanted to both push myself physically but also encourage people around me to flex their generosity muscles. I committed to match funding all donations up to £1000, and this £1000 would be outside of my standard 10% GWWC pledge (such that the match was counterfactual). I raised £440 in the end so I donated half of that to each of the charities I was fundraising for. The fun surprise was that my partner decided to also match fund everything that was donated, so she also gave £220 to both charities. The power of generosity!

- For context on THL UK, they’re an amazing charity that is relentlessly focused on reducing the greatest suffering experienced by animals. As such, they campaign against major food businesses (e.g. supermarkets) whose egg or chicken products confine chickens to tiny cages, or whose genetics lead to lives full of suffering. Globally, The Humane League already managed to secure over 3,000 commitments from food companies to free millions of hens from cages and they are one of the most impact-focused organisations in the animal movement. I also know members of the THL UK team personally and think highly of their work and plans for the future.

- Hamlin Fistula UK - £220

- As above in terms of the amount.

- Hamlin Fistula UK is a charity that’s pretty new to me, which I found when trying to figure out the organisations I wanted to support for my triathlon. A not particularly well-known injury, an obstetric fistula is a hole between the birth canal and the bladder or rectum due to obstructed labour without adequate healthcare. Its health and social impacts are massive. It leaves survivors leaking urine or faeces – and sometimes both – through their vagina. Sufferers of obstetric fistula are often subject to severe social stigma due to their smell and perceptions of uncleanliness. Almost all sufferers of fistulas are in very low-income areas with poor healthcare, so they often receive little medical treatment to cure this. You can read more about the condition here and I picked this group due partially to The Life You Can Save’s positive evaluation of a similar charity and some of my own research.

- Animal Welfare League – £202

- As above for Animal Advocates International in terms of the deciding process. We thought Animal Welfare League was doing impressive work in Ghana to build a network of cage-free farmers, to slow down the intensification of egg farming. In addition to this, they also conduct campaigns against companies that are using caged eggs, encouraging them to transition to cage-free eggs.

- Giving Green - £100

- Giving Green is a US-focused climate charity evaluator that I think does great work to find and promote effective climate charities. Honestly, it’s crazy to think this service didn’t exist before Giving Green as the climate nonprofit field is filled with so many organisations, receiving large amounts of donations, that probably have a negligible impact on reducing carbon emissions. Overall, I think they have a great team that conducts extremely thoughtful research and I found their 2023 recommendations quite interesting, finding several promising charities that I would never have heard of otherwise.

If anyone wants to chat or get more information about the charities above, suggestions for other impactful places to give, or about taking the Giving What We Can pledge, please reach out and I’m happy to be useful if possible.

Thanks for sharing this thoughtful post on your giving journey, James. And thanks for everything you do. Everyone on the Giving Green team is excited to continue to follow your work.

James this is great! I really like your framing of donations as in line with other personal actions; I've seen the FP graph but never actually interpreted it in the way you have.

Semi-related ramble, I've been workshopping this idea of giving as a way of expressing agency—especially when it comes to climate, I think a lot of people turn to plastic bags etc. because they want to feel like they're directly responsible for a Good Thing. People want to see and feel the impact of their actions, and donations don't often provide that sense of "I did this, and it meant something". I think a framing of donations as one of many possible actions actually might break that hesitation down a bit (and specifically, is related to some lefty mutual aid thoughts about money as one of many resources we offer in community). Will experiment with this, thanks for the idea :)

(disclaimer: personal hat on! I do fundraising in my non-work organizing spaces)

Executive summary: The author has pledged to donate 10% of their income each year to effective charities, believing that those living in wealthy countries have a moral duty to help alleviate suffering given global inequality. They outline why they took the pledge, where they donated in 2023, and encourage readers to consider doing the same.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.