Some career paths may be highly impactful but are limited in the number of positions available before they reach saturation. Other career paths have a far greater capacity for involving more people. This factor could be considered the “scale” of the career path, or to use a less commonly used phrase in EA, it could be considered to have high absorbency. I think the importance of a career path’s absorbency has been undervalued in the EA movement thus far. Career choice is often framed from an individual viewpoint, but when the needs of the broader movement are considered, you sometimes end up with a different perspective.

Abstract example

Let's take the example of two careers; A and B. A is low absorbency (let’s say it has capacity for two new people) but is a highly impactful career. B is high absorbency (let's say it has room for 100 people) but is a somewhat less impactful career (let's model it as half as impactful per person). If we run a simulation with 100 people considering the paths from an individual perspective, each individual might consider both careers, apply for A and inevitably 98 of them will be disappointed. I believe that in many cases, the psychological impact of rejection from career path A causes people to pursue career C (a career with no impact) rather than moving towards career B. Often they do this with the notion that they might apply for career A again in the future. In this model it's clear the optimal distribution would be two people taking job A, and 98 taking job B. If we assume that those who fail to get job A choose job C in all cases, then in this model it is interesting to note that it would be more impactful for everyone to apply for B rather than A.

Practical example

If we take this out of the abstract, we can look at commonly talked about career paths such as founding charities or other projects, and working for EA organizations. Many of the top recommended career paths in EA are very low absorbency. In fact, this is a commonly stated reason (in different terms) for why EAs are less excited about outreach. Bringing 100 new EAs on board is less impactful if only a handful of them can be utilized by the movement in top careers. Given the considerable variance in personal fit, and the relatively uncertain estimates of the impact of different career paths, it makes sense to take a more modest approach. Having some supported career paths that are both impactful and highly absorbent is similar to looking for top charities that have high ability to scale, even if their cost-effectiveness is not equal to a much smaller but far more cost-effective charity.

Examples of low absorbency career paths:

- Charity entrepreneurship

- Working for an effective altruism organization

- AI safety researcher

Examples of high absorbency career paths:

- Working in policy

- For-profit entrepreneurship

- Earning to give

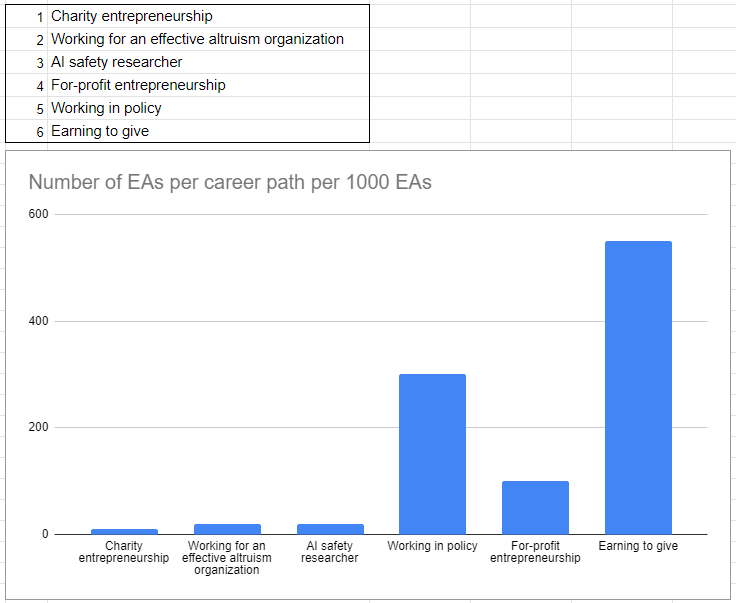

If we put these in a simple ordered list many of the low absorption career paths might do well. But if we put them into a chart portraying ideal distributions of talent utilization across the movement per 1000 EAs as a whole, we get a very different picture.

(These numbers are not necessarily the exact ratio or order I would put these in; they were chosen to deliberately highlight career paths that would differ depending on how we consider them).

Which approach the EA movement endorses will make a big difference in how excited people feel about taking different jobs. If you decide to earn to give, are you settling for job six on the list or do you see it as embracing the job that is actually the most impactful for most EAs to do? The framing transforms how a role feels. I think that we should give weight to both perspectives and include such considerations in discussions. I would not advocate for exclusive use of a chart that highlights absorbency like this, but I do think it’s a useful perspective and could lead to a lot of positive outcomes.

Support for high absorbency career paths benefits low absorbency career paths

Even if a career path that has low absorbency is the most impactful by far, it still makes sense to have a broader set of recommendations. I personally think charity entrepreneurship is the most impactful career path for people who are a good fit for it, but I know that is going to be a pretty small % of even the most talented EAs. If the EA movement had a couple of respected, impactful, high absorbency careers, it would be easier to do outreach and see a broader set of people happily engaged within EA. I expect I would get more strong applications for even the fairly specific career path of charity entrepreneurship. If someone is under the impression that their impact is trivial unless they do charity entrepreneurship, they could be put off EA. If they do not get accepted to our first round they don’t tend to tell their friends and connections, or skill up and apply again. On the other hand, if a related high absorbency career was also socially acceptable, approved of and supported, (say for example; for-profit entrepreneurship) then that person can potentially find a great career that makes an impact and their friends may also get into EA (maybe one of which is an even better fit for charity entrepreneurship than they were). It would also make it easier to encourage someone to apply for the CE program even if you were not confident that they would be successful. Rejection is not such a devastating blow when there are other well respected career paths available. In summary; having these paths allows better outreach and retention of EAs, creating a better and less zero-sum community dynamic.

See also posts tagged with scalably using labor.

Thanks for the post! Absorbency could be a 4th factor in the ITN framework for comparing career options. I'm curious about how 80,000 Hours considers absorbency in their list of top-recommended career paths.

Bella from 80k here — I really liked this post, and think it points to something important - thanks for writing it!

The ‘absorbency’ of a career path is one of the things we take into account when we decide what to recommend. For instance, being a ‘public intellectual’ is something that can probably absorb only a few people, which is why it’s lower down on our list of top recommended career paths (and we note this in the profile itself, too).

(AndreFerretti asked whether 80k considers absorbency below, but I thought I'd post as a comment not a reply since it might be of general interest) :)

Great idea. I notice a huge disconnect between the idealized ranking of high impact careers 80K puts out and what it actually takes to move people on the ground into higher impact roles, and the high emotional costs of trying to enter low absorbency fields is definitely one of the factors. On a population level, I agree that it would probably be higher EV to recommend careers more people are more likely to be able to successfully enter.

Potentially also worth mentioning: the career capital benefits of working in some roles that themselves might not have a high degree of direct impact.

With that point in mind—combined with frustrations over the seemingly low degree of absorbency in the career paths I was interested in—I wrote this: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/HZacQkvLLeLKT3a6j/how-might-a-herd-of-interns-help-with-ai-or-biosecurity

Basically, I suspect that there are some fields where the "absorbency" could be artificially inflated in a way that might only have roughly net-neutral direct impact in the short term, but which could produce meaningful longer-term benefits by, e.g., improving the skills and application-competitiveness of people with shared values/goals in AI or similar fields.

Thanks for writing this up! Just a few rough thoughts:

Regarding the absorbency of AI Safety Researcher: I have heard people in the movement tossing around that 1/6th of the AI landscape (funding, people) being devoted to safety would be worth aspiring to. That would be a lot of roles to fill (most of which, to be fair, don't exist as of yet), though I didn't crunch the numbers. The main difference to working in policy would be that the profile/background is a lot more narrow. On the other hand, a lot of those roles may not fit what you mean by "researcher", and realistically won't be filled with EAs.

I'm also wondering if you're arguing against propagating the "hits-based approach" for careers to a general audience and find it hard to disentangle this here. There's probably a high absorbency for policy careers, but only few people succeeding in that path will have an extraordinarily high impact. I'm trying to point at some sort of 2x2 matrix with absorbency and risk aversion, where we might eventually fall short on people taking risks in a low-absorbency career path because we need a lot of people who try and fail in order to get to the impact we'd like.

To check, is high vs low absorbency the same as claiming that different careers have different rates of diminishing marginal returns?

Toy example: we might think that in career A, the first person doing it brings 1000 units of value, but each additional person bring 10 fewer units of value. However, for career B, the first person doing it brings 200 units of value, but each additional person brings 1 less unit.

In this case, once you've got 80 people doing A, the marginal value of the 81th would be 190, so you'd then want to switch to having people do B. Career B we might call 'higher absorbency', but whether you want to push people to A or B depends on how many people you have.