I have recently looked into the threat of 'peak phosphorous' and thought I would quickly share my findings, as phosphorous is arguably one of the more plausible 'peak resource theories'. I conclude that the risk of phosphorous depletion to global food security are minimal.

***

‘Peak phosphorous’ is one of the more popular ‘peak resource’ theories, along with ‘peak oil’.[1] Phosphorous is essential for food production, and has no substitutes. Organic sources of phosphorous, such as crop residues, food waste, excreta, are classed as renewable. Phosphate rock on the other hand is classed as non-renewable and finite because it cycles from the lithosphere to the hydrosphere at rates of millions of years. When they are used in agriculture, phosphorous molecules are not being destroyed, they are just being redistributed around the world.[2] But still rock phosphate is, for practical purposes, finite because, once used, it cannot feasibly be retrieved for millions of years, at least at reasonable energetic cost.

Since supplies of phosphorous rock are finite, many argue that if current consumption continues, unless remedial action is taken, phosphorous use will peak in the next few decades, which might threaten global food security or even lead to global catastrophe.[3]

Before we discuss this, when considering peak resource theories, it is important to define the difference between reserves and resources (USGS p195):

Resource = A concentration of naturally occurring phosphate material in such a form or amount that economic extraction of a product is currently or potentially feasible

Reserve base = The part of an identified resource that meets minimum criteria related to current mining and production practices including grade, quality, thickness and depth.

Reserve = The part of the reserve base which can be economically extracted or produced at the time of the determination. This may be termed marginal, inferred or inferred marginal reserves. This does not signify that the extraction facilities are in place or functional.

On this definition, reserves are a dynamic figure: they will change depending on demand, scarcity and market prices. If scarcity increases, then the price will increase, producers will have greater incentive to find and exploit new reserves, and consumers will have incentives to economise on consumption or to recycle.

Resources are also dynamic as we might discover new deposits that we did not previously know about.

As we would expect, reserves of phosphorous change significantly all the time. In 2020, the US Geological Survey estimated that phosphorous reserves were 71 billion tons (p123), up from 16 billion tons in 2010 (p119).

In 2020, consumption of phosphate was 47 million tonnes. At current rates of consumption, it would take 1,500 years to use up the world’s phosphorous reserves, on the (false) assumption that reserves will remain static. According to the US Geological Survey, phosphate rock resources are 300 billion tons. So, at current rates of consumption, it would take more than 6,000 years to use up all phosphorous resources.

[EDIT: See the comment by Dave Denkenberger below. Assuming that current consumption continues and reserves stay static, reserves will be used up in 260 years, not 1500. For resources, the true figure is 1,390 years]

Moreover, there is ample scope for improvement in the efficiency of consumption of phosphorous.

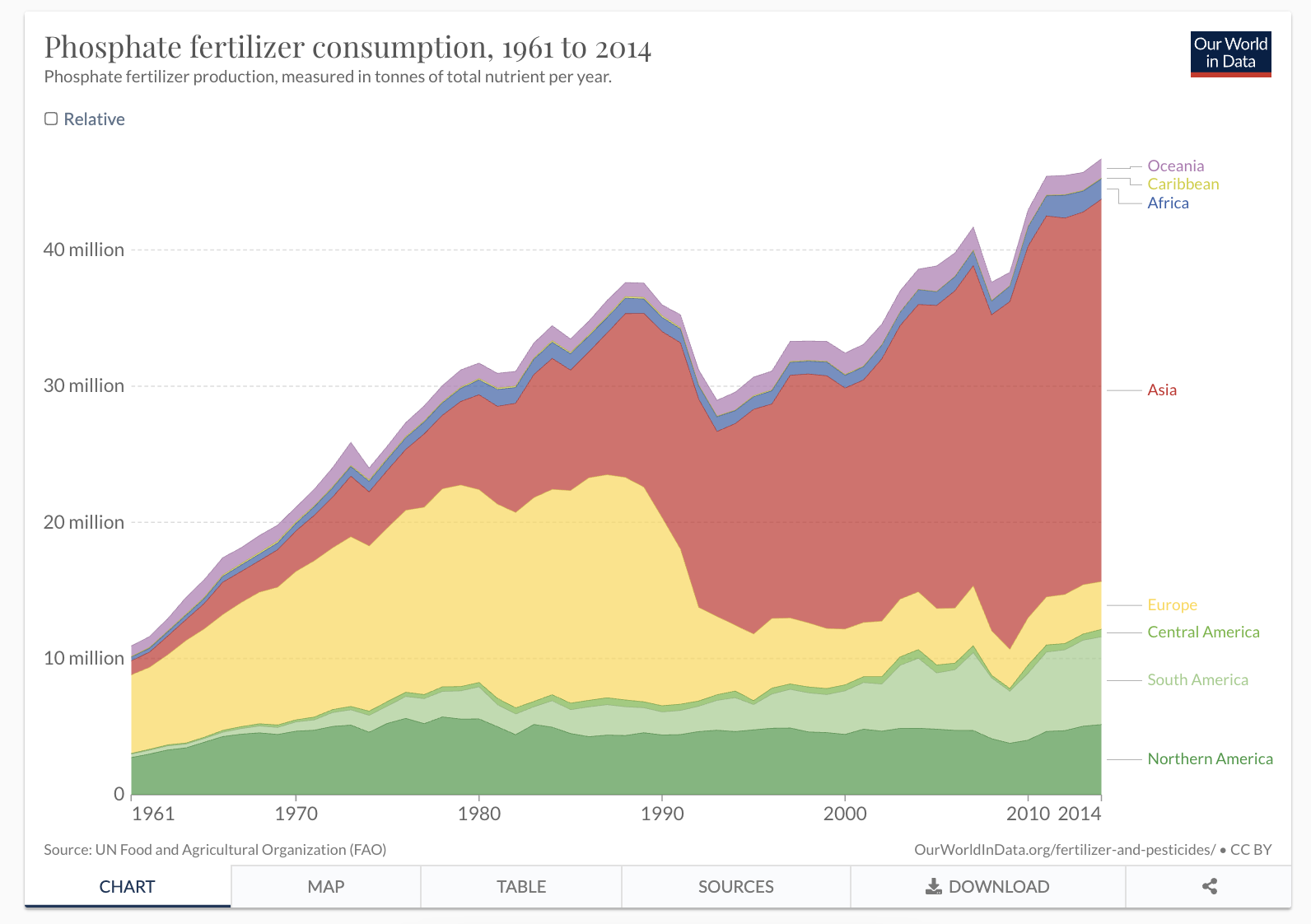

As this shows, despite huge increases in food yields, phosphate consumption has been flat in North America since 1970 and declined dramatically in Europe since 1987.

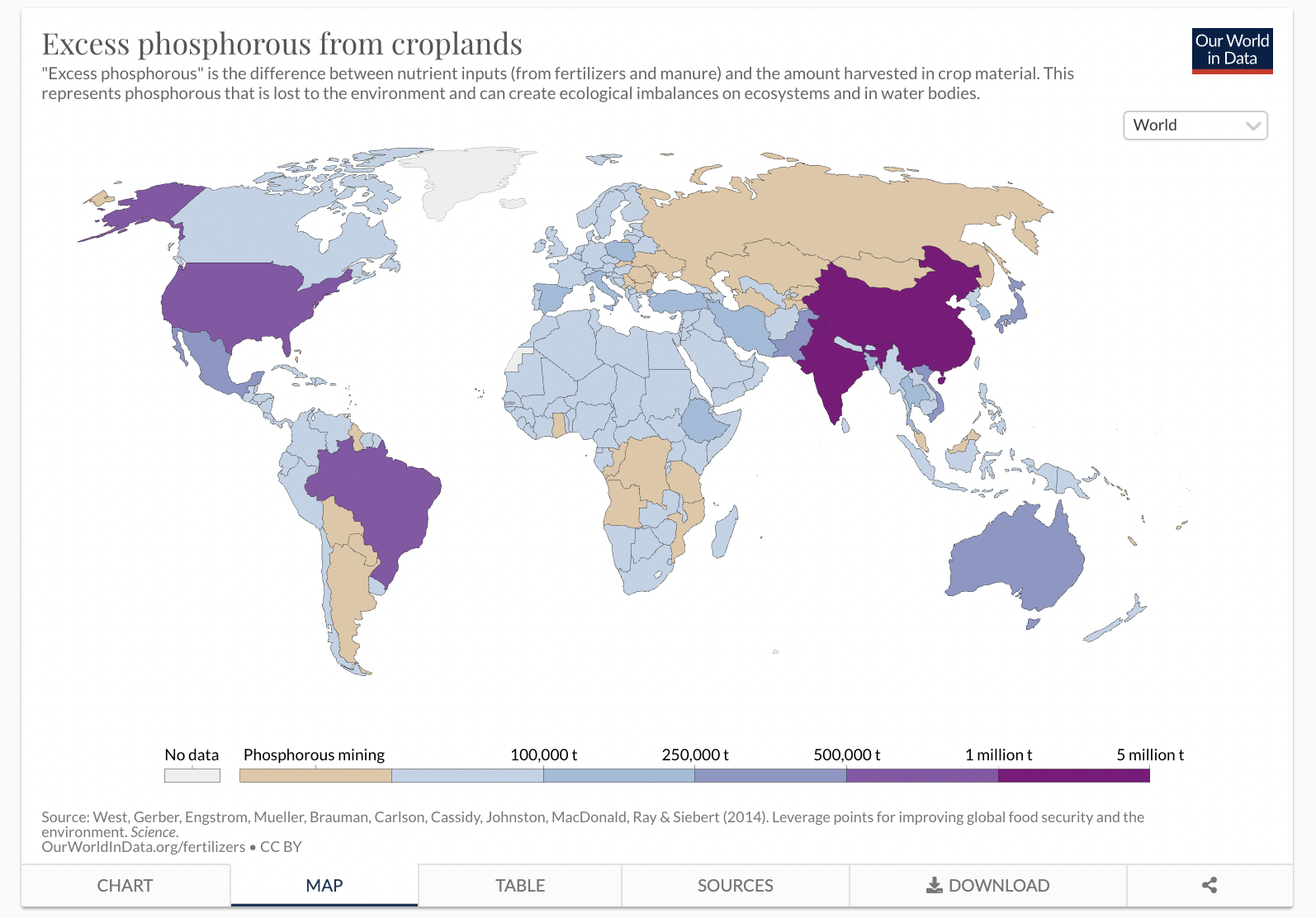

Fertiliser use in low and middle-income countries is much less efficient than in rich countries. Li et al (2015) estimate that in China 2.2kg of phosphorous per hectare was lost in crop and animal production systems, compared to rates of 0.4kg per hectare in Sweden and 0.5kg per hectare in the UK and Ireland.[4] This suggests that fivefold phosphorous efficiency improvements are possible just by moving China to Western standards.

In general, the use of phosphorous is very inefficient. 80% of the phosphorous in rock never reaches the food consumed by humans, but is lost at all stages. During mining and fertiliser production, as much as 30–40% of phosphorus can be lost during extraction and primary processing, while much of the phosphorus entering livestock and cropping systems ends up in manure and soils respectively[5]

If the price of phosphorous does rise due to mounting scarcity, there would be lots of scope to economise on phosphorous consumption, and huge market incentives to do so.

Phosphorous depletion poses minimal risks to agriculture.

Footnotes

[1] Dana Cordell and Stuart White, ‘Peak Phosphorus: Clarifying the Key Issues of a Vigorous Debate about Long-Term Phosphorus Security’, Sustainability 3, no. 10 (October 2011): 2027–49, https://doi.org/10.3390/su3102027.

[2] "However, the element phosphorus is not running out. According to the Law of Mass Conservation, phosphorus molecules cannot be created or destroyed. There are a fixed number of phosphorus atoms on the planet (meteors aside) and phosphorus cycles naturally between the lithosphere and hydrosphere, between land, biota and soil and between aquatic biota and aquatic sediments. Further, phosphorus is the 11th most abundant element in the earth’s crust (amounting to some 4,000,000,000,000,000 tons P), so not considered a geochemically scarce element. Clarity in this regard is therefore important for scientific credibility. Discussions regarding shortage or scarcity are related to the irreversible depletion of high-concentration rock phosphate reserves and the economic and energetic barriers to their exploitation as discussed in the next section." Cordell and White (2011), p. 2029.

[3] For examples, see Vaclav Smil, We’re Not Running Out of Fertilizer. See also this post by CSER researchers. "Climate change’s impact on biosphere integrity (discussed in the previous section) could harm the human food system due to loss of ecosystem services, disruption of the cycles of water, nitrogen and phosphates, and changes in the dynamics of plant and animal health (Bélanger and Pilling 2019). Crossing this planetary boundary is already having severe implications for global food security, including loss of soil fertility and insect-mediated pollination (Diaz et al. 2019).

Systems for the production and allocation of food are already enduring significant stress. The sources of stress include climate change, soil erosion, water scarcity, and phosphorus depletion. The natural resource base, arable land and freshwater upon which food production rely are being degraded. While global food productivity and production has increased dramatically over the past century to meet rising demand from an expanding global population and rising standard of living, these constraints and risks are increasing the vulnerability of our global food supply to rapid and global disruptions that could constitute global catastrophes (Baum et al. 2015)."

[4] "On average, for the total arable area in China, an estimated total amount of 2.2 kg P ha-1 was lost from crop and animal production systems. This rate of P loss is quite high compared with that estimated for many developed Western countries, for example, 0.4 kg ha-1 year-1 in Sweden and 0.5 kg ha-1 year-1 in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland". (Li et al, Past, present, and future use of phosphorus in Chinese agriculture and its influence on phosphorus losses p. 277-278)

[5] "The global phosphorus flows analysis through the food production and consumption system in Cordell et al. [1] found that 80% of the phosphorus in rock never reaches the food consumed by humans—it is lost at all key stages. During mining and fertilizer production, as much as 30–40% of phosphorus can be lost during extraction and primary processing [38], while much of the phosphorus entering livestock and cropping systems ends up in manure and soils respectively. Losses in the ‘post-harvest’ food system (i.e., between farm and fork) have been largely ignored until relatively recently. The globalized food commodity chain has resulted in more players, more processes, further distances and increased trade of commodities. Longer production chains in turn contribute to more food losses in the transport, production, storage and retail stages [54]. While Smil estimated global food losses in the commodity chain at approximately 50% [55], Lundqvist et al. [54] went on to estimate the embodied water in food losses." Cordell and White (2011), p. 2041

I really like this, and would love to see more work in the "peak resource" field. Of all the doomsday scenarios that are...

...general risks from resource scarcity are the ones I feel most confused/concerned about. Is our farmland really deteriorating? Are we really running out of key minerals? Is biodiversity loss // mass extinction really going to destabilize human civilization?

(That link is what pops up when I Google "biodiversity crisis" — haven't reviewed, just using it as an example of the kind of thing I hear often.)

I absolutely agree with you - in this regard, I wrote a post about energy depletion based on what some experts on limits to growth are saying, like Richard Heinberg, Arthur Keller, Nate Hagens, Dennis Meadows and the like.

You can check it here : The great energy descent (short version)

I spent some time on this, there are 3 posts + a summary (and I also made a 140 page document that goes in deeper detail about specific aspects).

Energy is especially important as it allows the extraction and production of everything else, so if it peaks the rest probably peaks too some time later (including phosphorus)... and I feel that EA really underestimated this aspect.

I agree overall, but Wikipedia says the USGS says that 223 million tons of phosphate rock are mined per year, so 260 years of reserves.

Hi dave, thanks for flagging this. yeah this is on p123 here. It seems like mine production is different to total consumption - we're mining more than we consume it would appear. From the point of view of running out of the resource, consumption rather than consumption is what matters, and USGS says "World consumption of P2O5 contained in fertilizer and industrial uses was projected to increase to 49 million tons in 2024 from 47 million tons in 2020."

P2O5 is 44% phosphorus by mass. Wiki:

So I think reserves are in phosphate rock, so you need to have production/consumption in terms of phosphate rock, not in terms of P2O5. That's why it's only 260 years. It would be very strange if the mining of something were five times as much as the consumption, especially over the longer term.

ah good catch - i will make an alteration to the post

The worry about peak phosphorous was always small but present in the back of my head. Reading this gave me one thing less to worry about and this is very sharable for future discussions. Thanks for the nice and concise analysis!