The tricky thing with collapse is that all the possible proximate causes can interact with and cause each other. In an earlier post we discussed a literature review by Joseph Tainter (Tainter, 2023). Tainter lists three main kinds of events that have been identified as a cause for collapse: 1) external conflict, 2) internal conflict and 3) climate change. When we think about those it becomes clear that climate change could easily create external and internal conflict, but not the other way around. Does this mean that climate change is the ultimate cause for societal collapse?

Climate changes with bad societal outcomes are mainly caused by volcanoes

Before we dive into the gears of how climate influences society, we should first take a look at what kind of climate changes we are actually talking about. The climate on our planet is never static, but those changes are usually quite slow and easier to adapt to. The main problem of climate is when it changes quickly and without warning. This is most often caused by volcanoes. Due to improvements of paleoclimate analysis we now have a pretty good picture of when these volcanic eruptions happened. A good overview here is given by Sigl et al. (2015) where they reconstructed the climate of the last 2500 years from ice cores and a variety of other proxy comparisons to validate their main analysis. Especially between 500 BCE and 1000 CE volcanoes are a dominant driver of climate anomalies. Of the 16 main climate events they identified in that time 15 can be attributed to volcanoes. The mechanism here is that volcanoes emit sulfate aerosols. These scatter the incoming sunlight, reflecting a greater share of incoming light back into space and thus decreasing the total amount of energy that reaches the Earth’s surface (1).

Sigl et al. also state that they see volcanic eruptions and their subsequent effects on the climate as linked to the collapse of civilizations, but have difficulties with direct attribution:

“…a direct causal connection of these two large volcanic episodes and subsequent cooling to crop failures and outbreaks of famines and plagues is difficult to prove . However, the exact delineation of two of the largest volcanic signals - with exceptionally strong and prolonged NH cooling; written evidence of famines and pandemics; as well as socio-economic decline observed in Mesoamerica (“Maya Hiatus”), Europe, and Asia - supports the idea that the latter may be causally associated with volcanically-induced climatic extremes.”

A more recent study by Büntgen et al. (2020) goes a step further and directly looks into how much human history has been influenced by volcano-driven climate changes by combining historical records with climate reconstructions based on tree rings. They find a lot of historical examples of volcano triggered climate change that led to societal collapse or at least significant hardship for the people living at the time. They also highlight the following points:

- Population decline tends to coincide with cool summers and almost always follows volcanic eruptions.

- Population decline at such times is mostly caused by famine and pandemics (2).

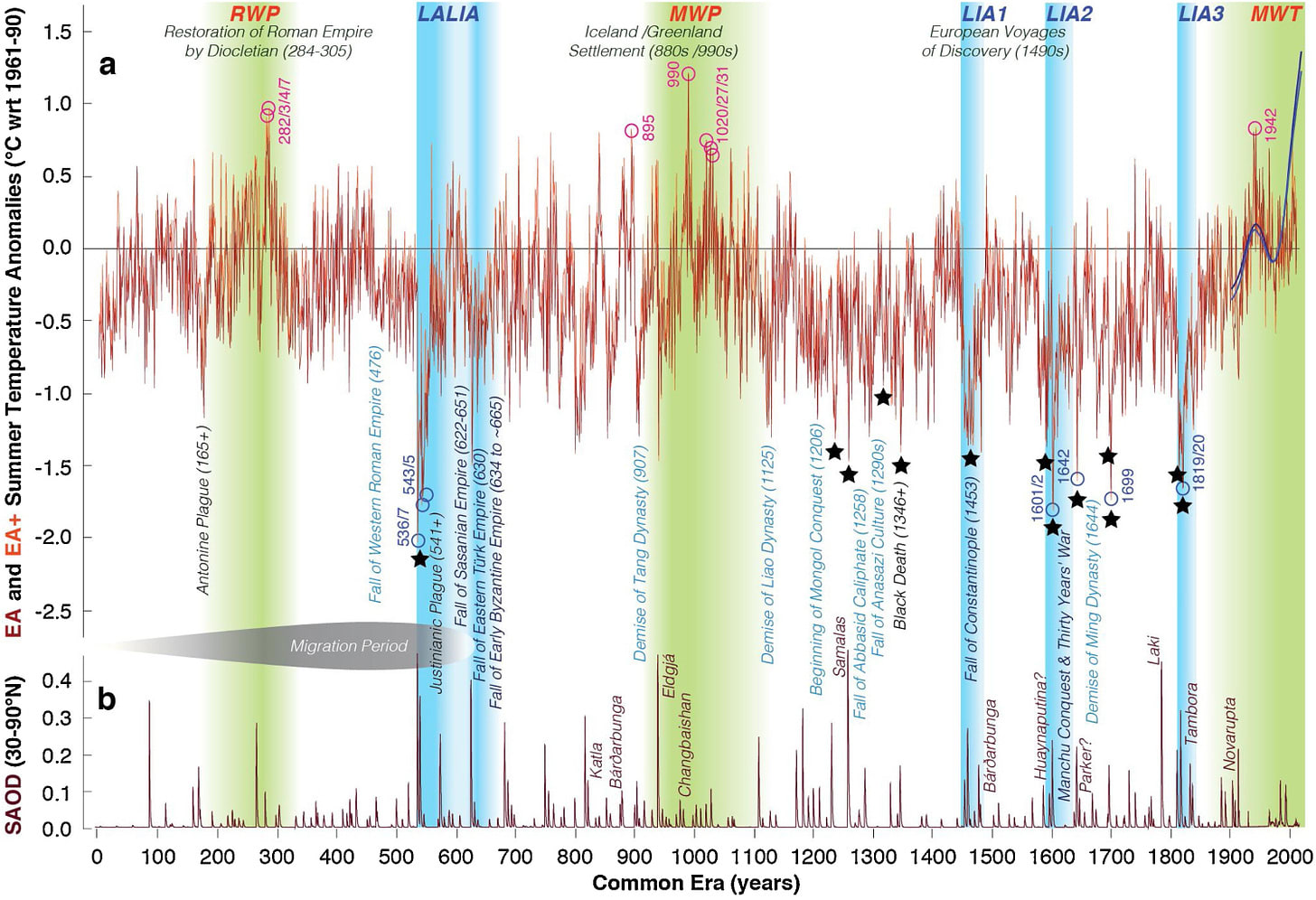

They summarize their results in an impressive figure (Figure 1). This figure brings together several datasets about temperature, eruptions and historical events (see figure description). We can see that significant events usually follow a major eruption. However, not all eruptions lead to major events, even if they are big. Usually, you have to have several major eruptions in a shorter time period to detect global, negative effects. The same effect could plausibly be caused by super-eruptions, but we have not experienced such an event in recorded history (yet). The biggest effects can be seen for the Late Antiquity Little Ice Age and the Little Ice Age, which we both discussed in previous posts.

Figure 1: Visual summary of volcanic eruptions (brown line at the bottom), temperature (red line), important historic events (as labels) and periods of warmer (green shade) and colder (blue shade) temperatures (Büntgen et al., 2020).

But history isn’t deterministic and simple, and there do seem to be cases where non-volcanic climate change leads to collapse. A prime example here is the Bronze Age Collapse (discussed in an earlier post here). While the overall story of this collapse is quite complex, more recent research indicates that it coincides with a megadrought lasting ~300 years (Kaniewski & Van Campo, 2017). In this case the origin for this shift in climate seems to be the always changing patterns of Earth’s climate and cannot be pinpointed to a single event. Still, it seems like volcanoes are the main factor for changes in climate, which adversely affect human populations.

We can find a pretty clear causality between climate and societal stability

We now know that climate anomalies are mainly driven by volcanoes and that times of climate anomalies do coincide with times where a lot of societies tend to struggle. So far we only have established correlation and not causation. However, a study by Zhang et al. (2011) tries to establish exactly this causation by an extensive data analysis. To do so they zoom in to the time of 1500 to 1800 (which contains the Little Ice Age, but also times of more warm and stable climate). Their idea is that to establish that climate changes cause societal strive, we have to establish that the timing is right.

The linkage they want to study is climate anomaly → drop in agricultural productivity → famine → epidemics → population decline (3). They track all those variables over time and can indeed show that they happen in the order they postulated. What seems especially noteworthy is that all those changes are tightly related to the price of grain. They find if the grain price rises above a certain threshold, you can expect a major negative period for the population shortly after. Based on this finding they turn their model around and try to predict major historical events using only the grain price. This identifies 1264-1359 and 1559-1652 as crisis periods and 1360-1558 and 1635-1800 as especially favorable times. All dates check out with historical events:

Negative prediction

- 1264-1359: Crisis period in the Middle Ages

- 1559-1652: General Crisis of the 17th Century

Positive prediction

- 1360-1558: Renaissance

- 1635-1800: Enlightenment

They also find that the grain price inversely correlates with the temperature and find that temperature derivations of more than -0.1 standard deviations can be seen as a crisis threshold for human societies, while times with warmer temperature usually also lead to more stable societies. They also use this temperature threshold to predict past events and come to the same conclusions as with the grain prices. All this in combination makes it seem likely to me that climate is the most important driver for overall societal well being. Though, this is always mediated by the societal response to the climatic shift, as we discussed in a previous post.

The model discussed by Zhang et al, is also implicitly validated by a study by Ljungqvist et al. (2023). The Ljungqvist paper is a massive historical assessment of past famines in Europe. They explore the reasons for a variety of famines and how they played out and, like in the model of Zhang, we can see again and again the pathway of climate anomaly → drop in agricultural productivity → famine → epidemics → population decline. However, it should be noted that approaches as used by Zhang and co-authors have been criticized in the climate change community as being overly simplistic, not addressing the uncertainties of past climate data enough, and assuming that correlation implies causation (Degroot et al., 2021). We should bear these critiques in mind, and interpret the results of Zhang et al. cautiously.

Theoretical underpinnings for the climate-society interaction

We have reviewed some evidence that climate is very likely the most important driver for societal collapse. Now we need some theoretical underpinning to make an actual scientific theory from this. Fortunately for us, a study trying to build exactly this was published recently by Timothy Lenton (2023).

The main idea in Lenton’s chapter is to transfer the ideas from tipping points (which we discussed in a previous post) from the climate system to the interaction of the climate system with human societies. Lenton argues that climate can be seen as an evolutionary pressure on societies. He bases this on arguments by others who have argued that the formation of states was a response to a changing climate. Yet, as we have seen, it has also been linked to many crisis and collapse events. This poses the question: “If climate deterioration is a credible trigger for the origin of complex societies, then how can it also be a trigger of their demise?”

Lenton frames his answer to the question in regards to complexity. He imagines the complexity space a society can occupy as a collection of attractors. These attractors represent viable ways you could potentially organize your society. Once you reach such an attractor (for example, becoming a nation state), there are feedback mechanisms which tend to keep you at roughly this level of complexity. Civilizations will also tend to introduce additional mechanisms to make their current position in the complexity space more stable. This entrenches their current positions and means a larger shock is needed to dislodge it. This makes the shift to another complexity state more abrupt, potentially increasing the chance of collapse if it happens. In general, you can see the movement from one complex state to another as quite disruptive, as it entails a major reorganization of your society. Imagine the large number of changes that were required to go from a medieval, feudal society to the nation states we have now.

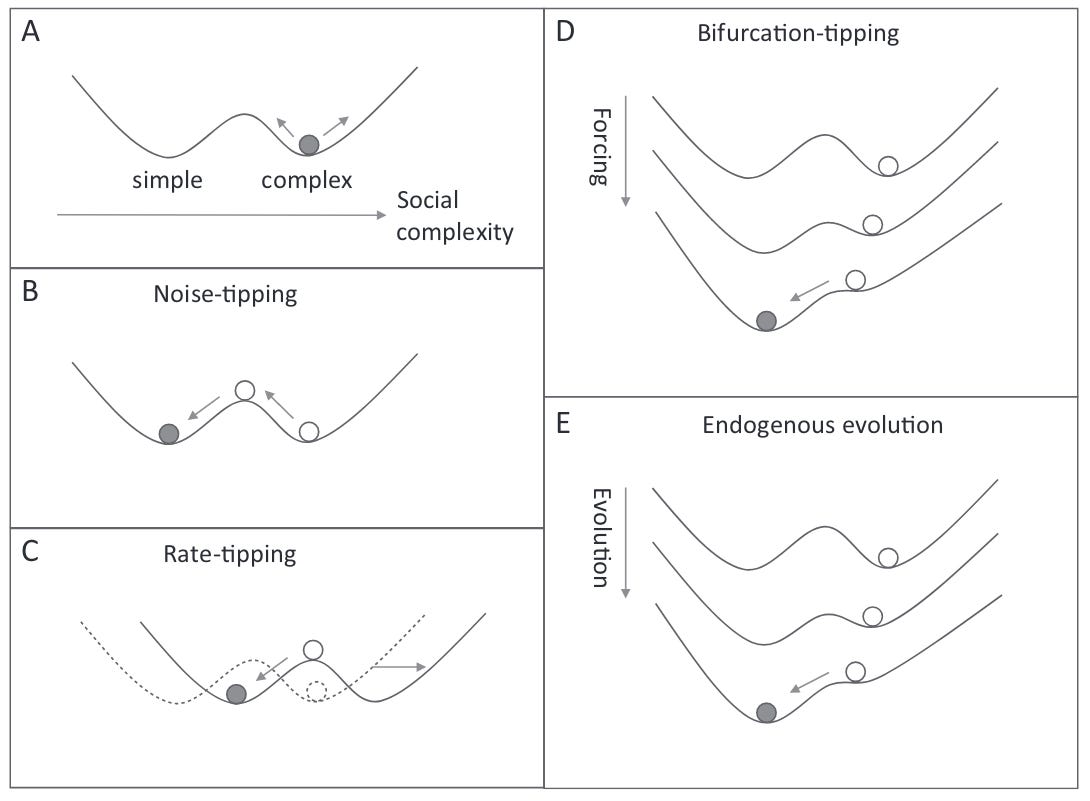

Societies will stay in their complexity position as long as they are not forced to leave it. They can be forced mainly by a variety of climate mechanisms (Figure 2):

- Extreme events in an otherwise stable climate: Your society gets hit by a once every 10,000 years flood, completely disrupting your way of life (Figure 2B).

- A changing climate after a disruptive event: A volcano erupts and climate feedback mechanisms lead to permanently less precipitation in the region you are in (Figure 2C).

- Slowly changing natural climate variability: The climate is never stable and changes over time, albeit slowly. This can remove the resource base a society is reliant on, but only gradually, making it hard to attribute to climate change (Figure 2D). For example, the change of the Sahara from a savanna to a desert.

- Evolutionary changes of the society: Internal dynamics of a society could make it less adaptive to the current climate state it exists in. This makes the society more vulnerable to all climate effects, increasing the likelihood of events that overcome its internal feedback (Figure 2D). An example could be the cultural adaptation that led to favoring a specific food for cultural reasons, even though it is less efficient than other food you could grow in your area.

Figure 2: Different types of tipping point collapse scenarios.

Once any of these processes overwhelms the internal feedback mechanisms of the society, Lenton sees two possibilities:

- Collapse: The climatic shock is too big for the society, leading it to a state where it is no longer capable of upholding the processes that undergird its complexity. It collapses and drops back to the last viable state, with the depth of the fall being dependent on how deeply entrenched the society was on its complexity level.

- Adaption: As the current state of complexity is not viable anymore, the society also has the possibility to undergo a considerable change, to reach the next attractor in the complexity space, which is more adaptive to the changed environment. Once there, the process begins anew.

Lenton’s description of collapse in this matter is helpful, as it gives us a more theoretical idea of how societies and climate interact when it comes to collapse. As we now have a model of how this should work, we can also go out in the world and try to actually falsify this hypothesis. Lenton describes how we could test his model scientifically: If we can detect a critical slowing down in important societal variables like grain harvest or currency value (4), it is likely that tipping point dynamics are the process which determines if a society collapses due to a certain event or not. This kind of analysis seems quite possible with the knowledge we already have today and I hope that somebody does it soon.

A complete theory of collapse?

In this post we have established that climate is a strong contender for a key reason for societal collapse, albeit mediated by the societal response and internal changes in the societal structure. However, this also means that we cannot look at climate alone. We always have to take into account the society as well. See for example, the highly variable reaction of societies to similar climate shocks, as described in an earlier post about the Late Antiquity Little Ice Age.

What is still missing is a more formal model that connects all these dots, especially in combination with the food system and epidemics and the overall capital of the society, which allows it to maintain unstable states at least for a while. This is also something that Lenton mentions at the end of his paper. To progress here we need to have first a feedback diagram that tries to define all the different interactions the climate, the food system and the society have with each other. Once this is established we can adapt this to a computational model and can see if it reliably predicts societal collapse. A good data source here is potentially the SESHAT database (Turchin et al., 2019), especially as they are currently compiling a dataset focused on societal crisis times.

Endnotes

(1) The scattering of the light also leads to bright red skies, especially when the sun is close to the horizon. This seems to be quite inspiring, as every time a major volcano erupts and paints the skies, we get a bunch of great art.

(2) Unfortunately, they don’t discuss if the pandemics are enabled by the famine or happen independently.

(3) The model in the paper is more complicated, but this seems like the main idea to me.

(4) As a reminder what critical slowing down means, here’s the explanation from my tipping points post: “The main way to detect tipping points are so-called Early-Warning Signals. They work by identifying changes in a system’s behavior as it approaches a tipping point. This change is often marked by a phenomenon known as critical slowing down, where the system becomes less resilient to disturbances. This means once a disturbance happens it takes longer and longer to get back to its original state the closer it is to the tipping point.“

References

Büntgen, U., Arseneault, D., Boucher, É., Churakova (Sidorova), O. V., Gennaretti, F., Crivellaro, A., Hughes, M. K., Kirdyanov, A. V., Klippel, L., Krusic, P. J., Linderholm, H. W., Ljungqvist, F. C., Ludescher, J., McCormick, M., Myglan, V. S., Nicolussi, K., Piermattei, A., Oppenheimer, C., Reinig, F., … Esper, J. (2020). Prominent role of volcanism in Common Era climate variability and human history. Dendrochronologia, 64, 125757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2020.125757

Degroot, D., Anchukaitis, K., Bauch, M., Burnham, J., Carnegy, F., Cui, J., de Luna, K., Guzowski, P., Hambrecht, G., Huhtamaa, H., Izdebski, A., Kleemann, K., Moesswilde, E., Neupane, N., Newfield, T., Pei, Q., Xoplaki, E., & Zappia, N. (2021). Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change. Nature, 591(7851), Article 7851. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03190-2

Kaniewski, D., & Van Campo, E. (2017). 3.2 ka BP Megadrought and the Late Bronze Age Collapse. In H. Weiss (Ed.), Megadrought and Collapse: From Early Agriculture to Angkor (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199329199.003.0005

Lenton, T. M. (2023). Climate Change and Tipping Points in Historical Collapse. In How Worlds Collapse. Routledge.

Ljungqvist, F. C., Seim, A., & Collet, D. (2023). Famines in medieval and early modern Europe—Connecting climate and society. WIREs Climate Change, n/a(n/a), e859. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.859

Sigl, M., Winstrup, M., McConnell, J. R., Welten, K. C., Plunkett, G., Ludlow, F., Büntgen, U., Caffee, M., Chellman, N., Dahl-Jensen, D., Fischer, H., Kipfstuhl, S., Kostick, C., Maselli, O. J., Mekhaldi, F., Mulvaney, R., Muscheler, R., Pasteris, D. R., Pilcher, J. R., … Woodruff, T. E. (2015). Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years. Nature, 523(7562), Article 7562. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14565

Tainter, J. A. (2023). How Scholars Explain Collapse. In How Worlds Collapse. Routledge.

Turchin, P., Whitehouse, H., Francois, P., Hoyer, D., Alves, A., Baines, J., Baker, D., Bartkowiak, M., Bates, J., Bennett, J., Bidmead, J., Bol, P., Ceccarelli, A., Christakis, K., Christian, D., Covey, A., De Angelis, F., Earle, T., Edwards, N., & Xie, L. (2019). An Introduction to Seshat: Global History Databank. Journal of Cognitive Historiography, 5. https://doi.org/10.1558/jch.39395

Zhang, D. D., Lee, H. F., Wang, C., Li, B., Pei, Q., Zhang, J., & An, Y. (2011). The causality analysis of climate change and large-scale human crisis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(42), 17296–17301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1104268108

I'm a little dubious about the dates given for "crisis of the middle Ages here". Wikipedia gives 14th and 15th century, i.e. 1300 to some non-negligible amount of time past 1400. That's at least a 3rd of a century after 1265-1359 for the beginning and at least 41 years after (and possibly much more for the end): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crisis_of_the_late_Middle_Ages The Wikipedia page on the Great Famine of 1315 (or 50 years after 1265) claims that it was the beginning of the crisis: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Famine_of_1315%E2%80%931317 'The famine caused many deaths over an extended number of years and marked a clear end to the period of growth and prosperity from the 11th to the 13th centuries.'

This suggests to me (though obviously doesn't prove) that the climate-based theory of crisis gets the last 3rd of the 13th century (1265-1300) wrong, and probably the first 15 years of the 14th century as well.

Having such a accuracy in your prediction is still pretty impressive when it comes to history. There is no super clear cut on how you define the start and end of things like "crisis of the middle ages", so I think the prediction is actually quite good.

It can be clear that there was no crisis before 1300 and clear that there was one in 1400 even if the boundaries are blurry.

How do you think about the relevance of evidence from pre-1800/pre-industrialized societies to questions of whether climate change will induce civilizational collapse going forward?

To me, I am always confused why people do these studies because society has clearly changed so dramatically that there seems to be very little to learn from how these societies responded to climate anomalies.

That's the big question of contemporary history. I discussed this a bit more here: https://existentialcrunch.substack.com/p/lessons-from-the-past-for-our-global

But in general I think that while our societies have changed a lot, many things have stayed the same. Especially, the food system and its importance for societies is still very similar. Also, if you read a lot of history, you come to realize that humans often tend to follow the same trajectories, in the sense of "history does not repeat, but it rhymes".

Views like the one from Lenton that I discussed in the post are also independent of the industrial revolution shift and if we could validate them, I think this would make a stronger case for the validity of historical comparisons.

Executive summary: Climate anomalies, often caused by volcanic eruptions, are strongly linked with societal crisis and collapse throughout history. Climate shifts can trigger declines in agricultural output, famines, disease, and conflict.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.