85% of Americans over the course of their lifetime will have their third molars, also known as their wisdom teeth, removed.

In supply chain management, a fun game to play is “five whys”. It means that when there’s a problem, you try to ask “why” at least five times to get to the root cause. Let’s try to apply this to a patient with pain in his upper jaw.

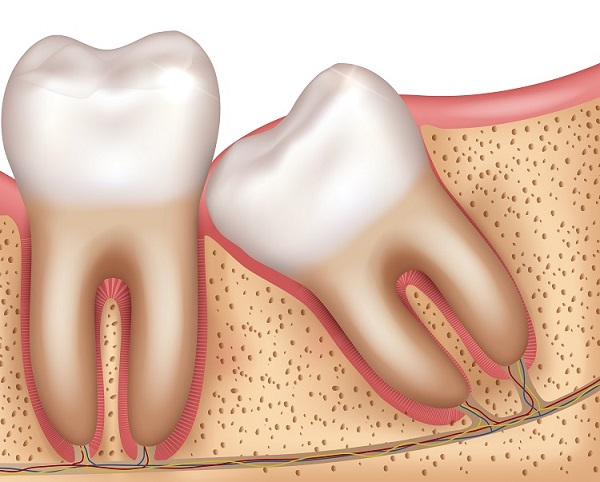

Why does the patient have pain in their upper jaw? Because their wisdom tooth is impacting their second molar.

Why is their wisdom tooth impacting their second molar? Because their upper jaw isn’t large enough for it to grow straight down.

Since the patient’s jaw is too small to accommodate the tooth, it cannot be made to point upright using braces or other methods. So, the tooth is extracted.

The thing that baffles me is, what is with the lack of curiosity about why the patient’s jaw is too small? We did not evolve in an environment where tooth extraction was easy or risk-free. So why would we evolve wisdom teeth that need to be extracted? It turns out, we didn’t.

From the article “Evolution of human teeth and jaws: Implications for dentistry and orthodontics”, published in 2012 in the journal Evolutionary Anthropology, the authors say:

Like caries and, probably, periodontal disorders, malocclusion is a ‘‘disease of civilization,’’ being much less common in fossil hominins and traditional foragers. Third-molar impaction for instance, occurs ten times more frequently in industrialized peoples than in hunter-gatherers. Further, fossil hominins and recent foragers tended to have an edge-toedge incisor bite rather than procumbent uppers overjetting lowers. The basic problem is a mismatch between jaw length and tooth size; there is insufficient room for proper implantation of our back teeth, so the front ones are pushed forward or forced out of proper alignment.

Put simply, fossils and traditional foragers don’t seem to have underbites, overbites, or problems with their wisdom teeth nearly as often as people in modern societies. Either our jaws have gotten smaller or our teeth have gotten bigger.

The standard hypothesis is that our teeth have gotten bigger. People in industrialized societies have less wear on their teeth, compared to foragers and hunter-gatherer fossils. Since wear makes your teeth smaller, that seems to explain the mismatch.

But the authors then go on to say:

It seems more likely, however, that our jaws are underdeveloped because softened, highly processed foods do not provide the chewing stresses needed to stimulate normal growth of the jaw during childhood. Human jaws have become shorter, on average, since the Paleolithic, a trend that is also seen in recent foragers who have made the transition to an industrial-age way of life.

This is reminiscent to me of trees that are grown indoors. When a sapling is pushed by the wind, it releases a hormone that helps it grow stronger. Trees that are grown indoors, where there’s no wind, will not do this and will break more easily in adulthood.

The obvious question is: if an underdeveloped jaw causes crowding, does it also cause other problems? I have some personal experience here, because I had my jaw surgically expanded when I was 22. (This is done over the course of a few months using something called an MSE appliance.) My opinion is that an underdeveloped upper jaw is a source of many problems.

The first problem is that it can prevent your tongue from suctioning to the roof of your mouth. That means that when you sleep, your tongue can fall back into your throat, causing snoring and sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is then treated with CPAP machines, which are expensive and inconvenient.

The second problem is that it results in a smaller nasal airway. Look at the difference in nasal airway size for this woman, who had her upper jaw expanded three times:

A small nasal airway limits the amount of air that can pass through your nose, encouraging you to breathe through your mouth. As it is impossible to breathe through your mouth while your tongue is suctioned, this also contributes to sleep apnea.

I suspect a small nasal airway is also easily clogged by mucus. Before I had my jaw expanded, I regularly had to change which side I slept on as one nostril or the other would get clogged. That hasn’t happened once since, even when I’ve gotten sick.

There is some evidence that the tongue’s pressure on the teeth when in suction also contributes to jaw development. The main evidence is the study Primate Experiments on Oral Respiration, where experimenters forced monkeys in the experimental group to breathe through their mouth by blocking their nasal airway.

All experimental animals gradually acquired a facial appearance and dental occlusion different from those of the control animals.

…

The common finding was a narrowing of the mandibular dental arch and a decrease in maxillary arch length

It’s possible that the improvements in nasal airway size are only the result of jaw-expansion surgery, and would not happen as a result of expanding the jaw naturally through chewing chewier foods in adolescence. I doubt it, and I’ll make a bet: $10 says hunter-gatherer fossils and modern-day foragers have larger nasal airways than people in industrialized societies.

It seems likely that many of these problems could be avoided if parents encouraged children to eat chewier food. Parents whose children breathe through their mouth should get their children examined for tongue-ties, macroglossia, and nasal obstructions. Finally, children experiencing crowding should be treated with expanders rather than extractions whenever possible. These interventions are cheap and mostly bottlenecked on improving awareness.

My suggestion would be to have no process other than general social sanctions. I don't think it makes sense to make any person or entity an authority over "effective altruism" any more than it would make sense to name a particular person or entity an authority over the appropriate use of "Christian" or "utilitarian".

I believe you're introducing a new kind of connection when you talk about usage of the heart-in-lightbulb image. I couldn't tell you who originally produced that image, but I assume it was connected to CEA. I agree that using an image with strong associations with a particular organization that created it might morally require someone to check in with the organization even if the image wasn't copyrighted.

I believe effective altruism benefits strongly from the push and pull of different thinkers and organizations as they debate its meaning and what's effective. Some stuff people do will seem obviously incongruous with the concept and in such cases it makes sense for people to express social disapproval (as has been done in the past).