Disclosure

I am a forecaster, and occasional independent researcher. I also work in a volunteer capacity for SoGive, which has included some analysis of the climate space in order to provide advice to some individual donors interested in this area. This work has involved ~20 hours of conference calls over the last year with donors and organisations, one of which was the Clean Air Task Force, although for the last few months my primary focus has been internal work on moral weights. I began the research for this piece in a personal capacity, and the opinions below are my own, not those of SoGive.

I received input on some early drafts, for which I am extremely grateful, from Sanjay Joshi (SoGive’s founder), as well as Aaron Gertler and Linch Zhang, however I again want to emphasise that the opinions expressed, and especially any mistakes in the below, are mine alone. I'm also very grateful to Giving Green for taking the time to have a call with me about my thinking here. I provided a copy of the post to them in advance, and they have indicated that they'll be providing a reponse to the below.

Overview

Big potential

I think that Giving Green has the potential to be incredibly impactful, not just on the climate but also on the EA/Effective Giving communities. Many people, especially young people, are extremely concerned about climate change, and very excited to act to prevent it. Meta-analysis of climate charities has the chance to therefore have large first-order effects, by redirecting donations to the most effective organisations within the climate space. It also, if done well, has the potential to have large second-order effects, by introducing people to the huge multiplier on their impact that cost-effectiveness research can have, and through that to the wider EA movement. I note that at least one current CEA staff member took this exact path into EA. With this said, I am concerned about some aspects of Giving Green in its current form, and having discussed these concerns with them, felt it was worth publishing the below.

Concerns about research quality

Giving Green’s evaluation process involves substantial evidence collection and qualitative evaluation, but eschews quantitative modelling, in favour of a combination of metrics which do not have a simple relationship to cost-effectiveness. In three cases, detailed below, I have reservations about the strength of Giving Green’s recommendations. Giving Green also currently recommends the Clean Air Task Force, which I enthusiastically endorse, but who Founders Pledge had identified as promising before Giving Green’s founding, and Tradewater, who I have not evaluated. What this boils down to is that in every case where I investigated an original recommendation made by Giving Green, I was concerned by the analysis to the point where I could not agree with the recommendation.

Despite the unusual approach, especially compared to standard EA practice, the research and methodology are presented by Giving Green in a way which implies a level of concreteness comparable to major existing charity evaluators such as Givewell. As well as the quantitative aspect mentioned above, major evaluators are notable for the high degree of rigour in their modelling, with arguments being carefully connected to concrete outcomes, and explicit consideration of downside risks and ways that they could be wrong. One important part of the more usual approach is that it makes research much easier to critique, as causal reasoning is laid out explicitly, and key assumptions are identified and quantified. When research lacks this style, not only does the potential for error increase, but it becomes much more difficult and time-intensive to critique, meaning errors in the analysis are less likely to be identified and publicised.

There being considerable room for improvement in Giving Green’s analysis is not, of itself, a major issue. Giving Green is a new organisation, which is primarily the work of two people in their spare time, and mistakes as a new organisation should be expected, let alone a new organisation with considerable time constraints. For example, GiveWell made many mistakes in its early years; in addition, concerns were raised productively about poor research quality at ACE a few years ago, and the impression I have from people who were involved at the time is that things have since substantially improved.

Media coverage risks overselling

Giving Green has, however, had an extremely successful launch, and has enthusiastically been promoted as a highlight of the effective giving/EA community. In some cases, I think that this promotion has implied a level of certainty behind Giving Green’s recommendations beyond that which is warranted, and indeed beyond that which they themselves have.

For example, this Atlantic article describes Giving Green as follows, before directly comparing them to Givewell:

Giving Green is part of the effective-altruism movement, which tries to answer questions such as “How can someone do the most good?” with scientific rigor. Or at least with econometric rigor…

This Vox article lists recommendations by Giving Green alongside Founder’s Pledge recommendations, describing both as:

the most high-impact, cost-effective, evidence-based charities to donate to if you want to improve US climate policy

Giving Green has also been highlighted in various more internal EA discussion, including an extremely positive post on the EA Forum, as well as a more neutral writeup in the Effective Altruism and Giving What We Can newsletters. The (even newer) organisation High Impact Athletes mentions Giving Green alongside Founders Pledge as a source of recommendations in their FAQ, though they do not feature prominently elsewhere. Edit: the reference to Giving Green has now been removed. While this piece was being drafted, another new organisation launched, with the aim of promoting and facilitating effective giving in Sweden. They list GiveWell, Giving Green, and ACE with equal prominence, again strongly implying an equivalence between the three. Having started this post with the case for why I am excited to see the emergence of an organisation like Giving Green, especially given this media success and their extremely slick website (seriously, go look at it), I am concerned that, especially among EAs, the lack of quantitative and rigorous analysis, even though it has been implied, poses a nontrivial reputational risk, especially if the headline recommendations are promoted without adequate qualification.

Finally, it feels like both Giving Green, and the EA community, could have seen this coming. Cool Earth was, for a long time, something like the default EA answer to the question “I really want to give to a climate charity, which is the best one?”, despite what turned out to be significant flaws in the analysis. It is still, as far as I know, the only climate charity mentioned in “Doing Good Better”. Thanks to the excellent work of Founders Pledge, among others, it is no longer the case that any recommendation is better than none.

My goal with this piece

I hope that Giving Green will, at least while they are still growing and learning, consider changing the priority with which the organisations they have researched are displayed, so that potential donors are strongly encouraged to donate to organisations where Giving Green concurs with the research of the more established effective climate researcher, Founders Pledge. My current personal recommendation for individual donors interested in climate change, or for EAs talking to friends who are looking for donation advice, is the one organisation recommended by both Giving Green and Founders Pledge, Clean Air Task Force.

Details of what I’m concerned about, including questions I put to Giving Green and details of their responses, are below.

Giving Green’s overall approach

Carbon offsets

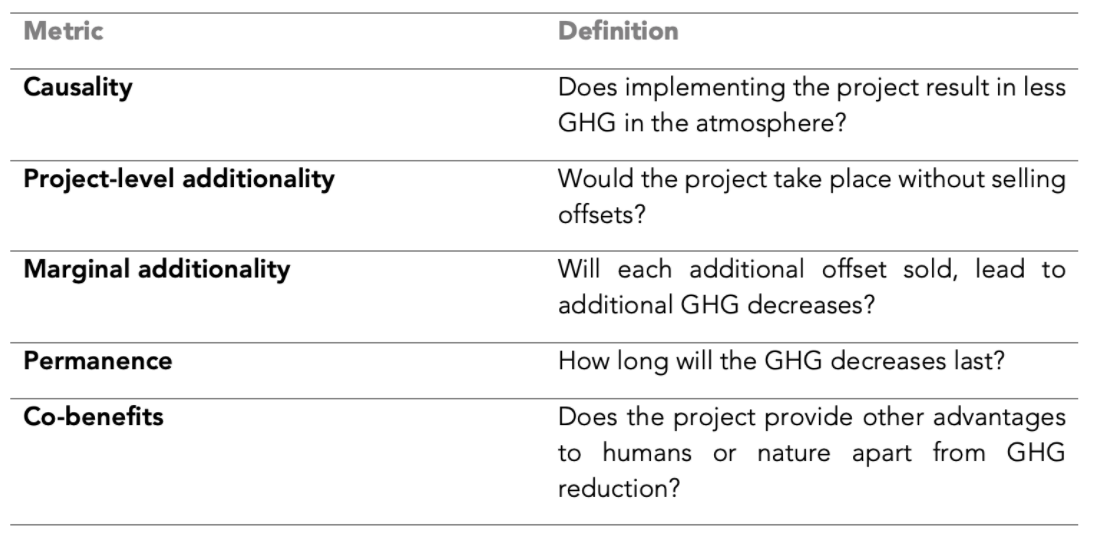

- Giving Green’s analysis of offsets consists of assessing five factors, none of which consider cost. Their approach is described in this document, from which the image below outlining their framework is taken.

- When I asked why cost was not explicitly modelled, Giving Green responded that the cost estimates produced by the organisations themselves are often unreliable, and that the true cost per ton of carbon is very uncertain and difficult to estimate. I agree with both claims.

- However, something being difficult to model is not, in principle, a reason not to try. It could well be the case that optimistic estimates of the cost-effectiveness of one organisation clearly underperform pessimistic estimates of the cost effectiveness of another, and in such cases there seems to be little reason to continue to recommend the first.

- Giving Green agrees with the consensus EA view that the framing of “offsetting personal emissions” is unhelpful, stating, for example, in their launch post that:

Carbon offsets are a mechanism to contribute to certified projects in an attempt to “undo” climate damage done by individuals or businesses. We find this framing unhelpful, and instead argue that individuals and organizations should view offsets simply as a philanthropic contribution to a pro-climate project with an evidence-based approach to reducing emissions, rather than a way to eliminate their contribution to climate change.

- Despite this, Giving Green has decided to make recommendations in the offset space, noting in the same article that:

In 2019 the voluntary carbon offset market transacted $330 million, and it looks poised for massive growth.

I would be very excited to see research by Giving Green into whether their approach of recommending charities which are, by their own analysis, much less cost effective than the best options is indeed justified. This analysis has not yet been performed by Giving Green, although they stated that they were very confident it would turn out to be the case.

Specifically, I’m interested in estimates/analysis of:

- What fraction of Giving Green’s donors will be people who come to Giving Green via EA or EA adjacent routes (where the most likely donation they would have made otherwise is to one of the FP top charities), and end up donating less effectively?

- What fraction of people who would otherwise not have come across EA climate change analysis, but who come across Giving Green, would have donated more effectively if Giving Green had presented them with only those recommendations where there is consensus on their effectiveness?

- Giving Green has not yet quantitatively modelled either aspect, although their impression of the climate donation space, which they view as comprised of several distinct groups, each with markedly different worldviews, gives them confidence in the portfolio approach.

Activism vs. Insider policy influence

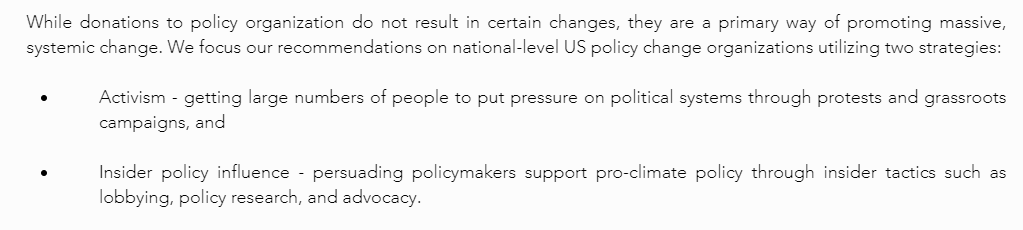

From Giving Green’s “Recommendations” page:

Similarly to the above, there has not yet been any quantitative analysis by Giving Green of the tradeoff between making better, narrower recommendations but risking putting some people off, and making donations that appeal to more people but include some options which are much less effective than others. This is concerning, as if organisations differ considerably in cost-effectiveness then ranking them equally is potentially a significant mistake. This would be a concern even if Giving Green currently recommended only one option, or made multiple recommendations with very similar EV. As the discussion below lays out, however, I think that Giving Green’s current recommendations do in fact differ dramatically in cost-effectiveness.

In Giving Green’s approach to policy recommendations, they lay out three reasons behind their choice not to rank organisations with different approaches: quantitative cost-effectiveness analysis is uncertain, not everyone agrees on the correct theory of change, and that donating to multiple organisations offers the opportunity to Hedge against political uncertainty.

- As discussed above, quantitative estimates potentially having wide error bars is not in itself a reason not to perform the analysis. It is possible that the difference between organisations is clearly larger than the size of the error. Secondly, the process of producing quantitative models forces an organisation to be explicit about their reasoning, in a way which makes it much easier to analyse and respond to.

- The existence of disagreement is similarly not, on its own, reason enough to eschew quantitative analysis, even if that disagreement is about political futures and/or moral weights. As a stand-out example of how the second can be handled, see Givewell’s work. As for political uncertainty, considering the way different political futures might affect the effectiveness of potential recommendations is exactly the sort of analysis it would be great to see from Giving Green.

- Hedging has been the subject of much previous discussion, so I won’t go into much detail here, other than to say that in general hedging arguments are not sufficient alone to justify spreading donations across options with significant differences in EV.

Specific recommendations

The Sunrise Movement Education Fund (TSM)

- The description of TSM as a “High-Potential” organisation (as opposed to Clean Air Task Force (CATF), which is described as a “Good Bet”, and is one of the organisations recommended by Founders Pledge), implied to me that Giving Green’s position was that the choice with the highest EV currently is CATF but that it is worth presenting both options.

- When I asked Giving Green about this, they made it clear that this was not the case. They believe that a direct comparison of the cost effectiveness of CATF and TSM would be too uncertain to be meaningful, and hence they fully endorse donations to either. In the Vox piece linked above, Dan Stein explicitly states:

I would push for a two-part strategy, because I think the way policy gets made is through these insider-outsider coalitions

- There are strong reasons, laid out below, to believe that TSM does indeed significantly underperform CATF. They can be thought of as having two key themes: low confidence in marginal impact, and uncertainty about the sign of the impact.

Low confidence in marginal impact:

- The case for donations to TSM being impactful on the margin feels thin; The Sunrise Movement has thousands of volunteers and is not obviously funding constrained. Similarly, within the field of climate change, progressive climate activism hardly seems neglected. If anything, grassroots climate activism has been the single most visible feature of the Western fight against climate change in the few years.

- Giving Green’s ITN analysis of US policy change ranked climate activism as the most neglected area, but the justification they provide is is based on data from six years ago:

Between 2011-2015, the largest donors in environmental philanthropy allocated about 6.9% of all their funding to grassroots activism and mobilization efforts, which are generally not as well funded as “insider” methods such as campaigns and lobbying

- Giving Green do not discuss the impact on neglectedness of the large and rapidly growing number of volunteers for TSM. More importantly, there is no mention of how different the activism landscape looks now compared to 2015. As one concrete illustration of how different progressive activism looks in a wider sense, Greta Thunberg is a household name. Her first protest was in 2018.

- The data I was able to find on TSM’s revenue from 2015 to 2018, show that it grew almost tenfold. It then, according to guidestar, quadrupled just from 2018-19.

Uncertainty about the sign of impact:

- Even in a world where potential CATF and TSM donors are different enough that recommending TSM does not meaningfully impact donations to CATF, and where marginal donations to TSM help them achieve their goals, this does not mean the recommendation of TSM is necessarily good in expectation.

- I have some concerns about TSM’s historic opposition to nuclear technology and CCS, despite broad consensus that both will be vital to keeping global warming at manageable levels.

- More worrying, TSM’s explicit strategy of attempting to polarise the debate rather than looking for consensus, seems like it could backfire extremely easily.

Making climate change a partisan issue might look promising in the short-term given the current Democratic trifecta, though the wafer-thin majority and existence of the filibuster somewhat dampens the case even there, but in even the medium term there is an obvious and potentially very large downside to such an approach. This would be concerning anyway, but given the proven track record of groups like CATF at achieving exactly the sort of bipartisan consensus that political polarisation could permanently damage, it seems very unwise to recommend both.

- The potentially negative effects highlight again the advantage of a quantitative model over merely picking “the best of each different approach”. It is no use that an intervention is the most promising for its particular strategy, if there is a significant chance of that strategy being actively harmful. It is notable that CATF, Giving Green’s other policy recommendation, who not only were first recommended by Founders Pledge but have since in addition been recommended by SoGive and Legacies Now, does not pose a significant downside risk, strongly indicating that it does better in expectation.

- While not directly related to the concerns discussed above, a choice of language in the TSM writeup is also concerning. Giving Green refers to TSM’s “non-partisan get-out-the-vote activities”. While, on a technicality, one could argue that these activities were non-partisan, writing in this way risks making Giving Green appear either naive or disingenuous. Though The Sunrise Movement Education Fund is registered as a non-partisan arm of the broader but obviously partisan Sunrise Movement, this line doesn’t feel integral to the analysis and consequently feels like it would be a good idea to cut.

BURN

Here, again, I have split the discussion into two sections. The first describes why I think the strength of the RCT evidence has been overstated, the second details why extremely strong evidence would be needed to recommend BURN given the specifics of how offsets work in this case:

Concerns about the presentation of RCT evidence:

- From Giving Green’s recommendation:

[We recommend] BURN stoves on the weight of strong Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) evidence in support of the causality of emissions reductions, as well as demonstrated co-benefits.

- The single RCT being referred to studied the effect of different pricing systems on willingness to pay. While evidence was also collected on fuel use, and a 154-person subsample was studied 18 months later, calling this “strong RCT evidence [of emissions reductions]” risks appearing sloppy or even deliberately disingenuous. When people hear “Strong RCT evidence in support of X”, it is reasonable for them to assume that the primary aim of the RCT was to investigate X, and this is not the case.

- Basing the analysis on a single RCT and then referring to this as “strong RCT evidence” does not appear consistent with the norms of other evaluators in the EA space (I believe this would be atypical for GiveWell, and can confirm that it would be atypical for SoGive). All the more so when the rest of the evidence base is highly heterogeneous.

- Giving Green does not recommend cookstoves in general due to a wider review of the evidence:

We do not feel comfortable recommending cookstove offsets in general, as the RCT literature shows that the required assumptions are frequently not satisfied.

When I asked Giving Green about this recommendation, they replied that the wider literature on cookstoves is heterogeneous, rather than outright negative. As the two principal uncertainties about the usefulness of cookstoves are with respect to fuel use reduction and long-term adoption, and the RCT above provides evidence about both of these, they feel it makes a strong case for BURN. I am less skeptical about BURN than I was following this exchange, however I still think that there is an important difference between

evidence about X extracted from an RCT studying Y

and

an RCT about X.

As well as the concern about transparency above, I note that picking the best looking intervention from a heterogeneous set makes you particularly susceptible to the optimiser’s curse, and that multiple hypothesis testing is a nontrivial risk even when dealing with RCTs directly investigating variables of interest. Most importantly, for the reasons detailed below, the evidence would need to be extremely strong in order for BURN to be worth recommending overall.

Specifics of donating to BURN:

- Even ignoring the concerns above, there is no concrete mechanism by which donations to BURN will lead to more cookstoves being sold. BURN themselves state donations will be

used to invest in research and development, as well as to fund certain aspects of customer engagement, branding, and warranty services.

There’s a plausible causal mechanism here which may lead to more stoves being sold, but isn’t Giving Green’s model of carbon offsets that people prefer them due to increased certainty? Again, if this was modelled quantitatively it would be useful to see, but without such modelling the recommendation is hard to understand.

- Furthermore, BURN is a company, not a charity, so there is less recourse to ensure that the marginal effect of a donation is to do good (as opposed to increasing profits).

- BURN plausibly saves its customers money in the long run. It was unclear to me whether this was the primary reason behind the recommendation, as the approach to recommending offsets claims the following:

Giving Green only uses GHG reductions to determine which offsets to recommend, and therefore it is not necessary for an offset to have co-benefits to gain our recommendation. However, as many offset purchasers would like to buy offsets with co-benefits, we highlight them in the analysis of our recommended offsets.

However, BURN’s endorsement on the Carbon Offsets page has the following label:

Decrease emissions and save families money

Giving Green confirmed when asked that this was not a factor in BURN’s recommendation.

Climeworks

- Not mentioning the substantial funding pipeline Climeworks has from Stripe seems like a significant oversight, especially if (as discussed below) the principal reason to fund Climeworks is that they might be better in the future. I expect almost all of the value of offsetting with Climeworks right now to be in marginally increasing the chance they end up as a successful company, given the tiny amount of carbon sequestered for the price. Stripe's involvement seems to notably reduce the risk they fail due to lack of funds, which is the main lever that buying offsets has to pull.

- Giving Green confirmed that the long-term effects of donations to Climeworks were the principal reason for the recommendation, however they did not agree with me that these effects being positive were conditional on Climeworks’s survival and eventual cost competitiveness. They argued that donations were able to send a price signal about permanent carbon capture which was important even if Climeworks ultimately failed.

- Giving Green state:

The main drawback of Climeworks is that it is currently very expensive (around $1000/ton) to remove carbon relative to other options. This may be justified by the fact that supporting Climeworks will hopefully go toward reducing the cost of their frontier carbon-removal technology. (emphasis mine)

- Giving Green confirmed that they have not attempted to model the expected value of the various long-term effects discussed above, or even the probability of Climeworks ultimately being successful. Some public forecasts on related topics do exist. Metaculus currently puts the chance of Climeworks’ pricing dropping below $50/T, by 2030, at 3%, conditional on its survival. Climeworks itself only has a long term price target of $100-200/T, though it is not clear whether this is adjusted for inflation. Metaculus currently puts the chance of it still existing in 2030 at 1 in 3.

- It is finally noteworthy that directly purchasing overpriced (in immediate terms) offsets is not the only way to try to positively affect the future of the offset market. Carbon180, another Founder’s Pledge recommendation, focuses on policy advocacy, business engagement, and innovation support for carbon removal/negative emissions technology.

Thanks, Alex, for writing this important contribution up so clearly and thanks, Dan, for engaging constructively. It’s good to have a proper open exchange about this. Three cheers for discourse.

While I am also excited about the potential of GivingGreen, I do share almost all of Alex’s concerns and think that his concerns mostly stand / are not really addressed by the replies. I state this as someone who has worked/built expertise on climate for the past decade and on climate and EA for the past four years (in varying capacities, now leading the climate work at FP) to help those that might find it hard to adjudicate this debate with less background.

Given that I will criticize the TSM recommendation, I should also state where I am coming from:

My climate journey started over 15 years ago as a progressive climate youth activist, being a lead organizer for Friends of the Earth in my home state, Rhineland Palatinate (in Germany).

I am a person of the center-left and get goosebumps every time I hear Bernie Sanders speak about a better society. This is to say I have nothing against progressives and I did not grow up as a libertarian techno-optimist who would be naturally inclined to wanting to solve climate change through technological innovation. Indeed, it took me over a decade of study, work in climate policy, and examination to get to the positions I am holding now which are very far from what I used to believe.

I should also state upfront that my credence in CATF and other high-impact climate charities does not come primarily from the cost-effectiveness models, which are clearly wrong and also described as such, but by the careful reasoning that has gone into the FP climate recommendations. John spent nine months working on the original FP Climate Report (to which I advised), I spent the majority of the last year reviewing many charities -- including CATF, CfRN, CLC, ITIF, Carbon180 and TerraPraxis -- and recommending some of those as high impact. Do I literally believe any of John’s or mine or anyone else’s model of an advocacy charity? No, of course not.

But the process of building these models and doing the research around them -- for each FP recommendation there is at least 20 pages worth of additional background research examining all kinds of concerns -- combined with years of expertise working in and studying climate policy, has served the purpose of clearly delineating the theory of value creation, as well as the risks and assumptions, in a way that a completely qualitative analysis that has a somewhat loose connection between evidence, arguments, and conclusions (recommendation) has not.

The fundamental concern with Giving Green’s analysis that I, and I think (?) Alex, have is not the lack of quantitative modeling per se, but the unwillingness to make systematic arguments about relative goodness of things in a situation of uncertainty, rather treating each concern as equally weighted and taking an attitude of “when things are uncertain, everything goes and we don’t know anything”. The impression one gets from reading the Sunrise recommendation and its defense is that a grassroots activism recommendation was needed for organizational variety reasons (given Giving Green’s strategy to reach a wider audience of segmented donors).

While one can have different opinions about the value of that given dilution concerns that Alex also mentioned, this is in principle not problematic with regards to the analysis. Where it becomes problematic is when pretending that the same rigor and reasoning that underlies a recommendation of CATF has been applied to the Sunrise analysis, which does not seem to be the case (while I lead the climate work at FP now, I should state here that John Halstead did the original analysis recommending CATF, so this is not quite as self-serving as it sounds).

While I am concerned about recommending offsetting in general and --as Alex mentions in his post -- think we should be very carefully modeling dilution effects before advertising offsets alongside high-impact options (or generally, before advertising low impact options), I did not read the offsetting recommendations in detail, so I will leave my comments to the TSM and TSM-CATF aspects in this comment.

I think there are a bunch of ways in which CATF is wrongly portrayed here and, in addition, many additional reasons beyond Alex’s that should make one doubtful about the claim that “we dont know whether TSM or CATF donations are better at the margin”.

While we do, of course, not know for certain, the evidence that we have points in a clear direction -- that donating to CATF and other similar charities (such as those featured in the FP Climate Fund) is much more impactful than donating to the Sunrise Movement Education fund (TSM in the following). Indeed, from the evidence we have, I would argue that there is a significant probability that donating to TSM at this point is net-harmful. Luckily, there is also a high probability that it is very low-impact at the margin.

Let me explain (after the summary).

SUMMARY

As I stated in my EAGx Virtual talk last year, I would like to understand the goodness of grassroots activism better. As such, I was quite excited to know Giving Green to be working on this and to read the analysis.

But reading the analysis, I don’t find myself having learned a lot about the expected goodness of the Sunrise movement because it appears more like an analysis of the positive case rather than a balanced all-things-considered-view.

As Alex has raised and I have expanded here, there are serious concerns both about (a) low marginal impact and (b) about the direction of that impact. These find no parallel in recommendations such as CATF.

While not impossible, it would be very surprising if something with (a) low marginal additionality and (b) severe uncertainty about the direction of marginal impact -- whether it is positive or not -- was the best thing we could fund in climate (or, undistinguishable from the best thing).

The main claim why we should expect that -- if I understand Giving Green correctly -- is the transformative nature of Sunrise, what they are doing just being that good. As I discuss below in the sections on “misconceptions about CATF” the claim that what Sunrise is doing is more transformative than what CATF is doing is -- at the very least -- controversial and not obviously true.

This leaves me in a situation where I would like to learn more about the goodness of the Sunrise movement from an all-things-considered analysis but where -- with the current information -- I don’t see strong reasons to think that Sunrise is anywhere close to the best things we can fund.

We are very confident that CATF and similar charities are an excellent translator of money into climate impact. We don’t know this for TSM and the weight of the evidence does not point in the direction of it being particularly likely that it is high-impact to donate to TSM at the margin.

SOME MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT CATF

Before diving into the detailed comparison between CATF and TSM it is worth noting some misconceptions about CATF that matter for this comparison.

1. Is CATF “incrementalist”?

The dominant frame in Dan’s comment and in the Vox piece with regards to CATF v. TSM is that CATF is “incremental”, “moderate” vs. TSM being “radical” and more likely to lead to transformative change. That there is something essential that can only happen if Sunrise and other progressive climate activists have more success.

I think this framing, while discursively resonant in current American debates between progressive and moderate Democrats, misses the point.

This is because the challenge of climate change is one of global technological transformation, not national politics and, as such, this frame is a lot less applicable than in issues where this framing might be more helpful (such as, say, civil rights).

While it is true that what CATF is doing -- not focusing primarily on a national target for the US etc. or advocating for a symbolic Green New Deal -- looks moderate and incremental, it is not when we consider the nature of the climate challenge which is allowing 9 billion humans to live poverty-free lives without cooking the planet. Solving this challenge has one necessary and, almost sufficient, condition -- ensuring that across all use cases low-carbon energy/industrial products are preferable to high-carbon ones or are so minimally inferior that realistic climate policy can bridge the differential even in settings with low willingness-to-pay for climate.

Because the US energy innovation system is so powerful and because the leverage from cost reductions and improvements is so large (~85% of global energy is fossil, US has a declining share of emissions and is now around 15%, cost reductions are the main driver of lowering carbon intensity in electricity etc., technological spillovers are the best way to make progress in a low-coordination, low willingness-to-pay setting), stuff that looks incremental -- advocating for tax credits for neglected technologies etc here., for a clean energy standard that also includes nuclear and CCS there etc -- is indeed quite transformative.

A better frame to compare CATF and TSM, in my view, than “incremental” vs. “transformative” is to understand CATF as an organization mostly taking political realities as a given (though doing some coalition building) that is laser-focused on ways in which they can make important differences -- with “important” informed by their deep knowledge of the issues and their proto-EA focus on things that are overlooked by the mainstream but critical to the overall puzzle. This is a transformative proposition of thought leadership, of changing the conversation, changing policy and, ultimately, the underlying technological base that allows us to decarbonize.

Indeed, it is quite plausible that this type of “quiet” climate policy -- focused on accelerating globally neglected technologies -- is far more potent than a Green New Deal that would primarily be focused on solutions that are far down the learning curves, already popular, selected for co-benefits such a job creation, etc.

TSM’s proposition is also transformative, though in a different way -- trying to increase attention to climate far more than what it is and push ambitious climate policy, embedding it in priorities that Democrats already have. This is also a transformative proposition.

In other words, we should not let our perceptions of “incremental” vs. “transformative” be guided by partisan conceptions of those terms; if we look at the climate issue closely and understand the importance of technological change at the heart of achieving global net-zero emissions those meanings might very well switch. Even if it doesn’t switch then at least both what CATF and what TSM are doing is transformative.

2. Is there a serious chance that CATF is negative?

There is also the assertion that CATF might be negative because, by heavily focusing on carbon capture and storage (CCS) and other technologies that help existing industries become close to carbon-neutral, they are giving a life line to fossil fuels or otherwise inhibiting climate progress.

While it is true that if we got CCS to work cheaply and efficiently, this would reduce the argument for transitioning away from fossil fuels for part of the energy mix, that’s a feature not a bug. The goal of climate policy is net-zero emissions, not 100% non-fossil fuels.

Leaving aside that OilPriceInternational is not exactly a neutral voice, let’s put their estimate into perspective.

They estimate that the 45Q tax credit could lead to something like 50 million tons of additional US emissions per year in 2035 through enhanced oil recovery (EOR) emissions. (Given the trajectory of US climate policy, this seems implausible). At the same time, right now 45Q is the most important carbon capture incentive policy in the world and it is the median expert view that -- if we are to achieve climate targets -- different forms of carbon capture (all of which covered by 45Q) will be used at Gigaton scale and that government incentives will be essential to drive down the cost and increase adoption.

So, if 45Q only leads to moving forward CCS deployment by 1GT a year, this “cost” of also including enhanced oil recovery in the 45Q bill would be a 5% cost on what would still look like an amazingly good outcome for the climate. Sure, it would be better if there were no increased emissions, but in the grand scheme of things -- and given how policy works -- better to have that policy with that negative side effect rather than having no CCS incentive policy at all.

This kind of cost is not analogous in magnitude to the very real cost of risks around Sunrise, such as an additional increase in polarization gridlocking important incrementally looking but transformative (see above) climate policy progress. It appears like a case of false equivalence.

REASONS TO EXPECT LOW MARGINAL IMPACT WHEN DONATING TO TSM

3. Grassroots activism might be good on balance, but still an implausible recommendation at the margin

This is an important point that is easily missed when discussing TSM as some of the discussion on TSM here and elsewhere is focused on non-marginal arguments, grassroots activism being generally useful as an outside-pressure force in an outsider -- insider model.

I would probably agree with the argument that the rise of progressive climate activism over the past four years has been net-positive, though there are also important caveats to this such as increased polarization of the climate issue, increased focus on catastrophic framings that are not in line with climate science, overly focused on 100% renewables vs. technology-inclusive decarbonization visions etc. But I take it as a given for the remainder that “on the whole” the world is better with Sunrise than without.

However, this does not at all mean that we should donate to TSM at this point. I agree TSM could have been a great philanthropic bet 4 years ago.

4. Grassroots activism might have been neglected ten years ago, but it is not neglected now

As Alex points out, the data for the neglect of grassroots activism are outdated -- and importantly so. Using data from 2011-2015 to evaluate the neglectedness of climate activism today is like using data from the nineties to say that the internet is not a big deal. Climate activism as a mass form of engagement has risen to the prominence with Greta Thunberg, with Extinction Rebellion, with Sunrise, with the Paris Agreement and the subsequent IPCC 1.5 degree report -- all of those happening at the earliest in late 2015 and many significantly later.

Luckily more current data on climate activism philanthropy are readily available.

For example, the ClimateWorks Foundation published a report in September 2020 which shows that US-focused public engagement -- the category under which grassroots activism falls -- received about 100 million on average between 2015-2019, which is about 27% of total US-focused climate philanthropy by foundations, a lot more than what the 2011-2015 numbers that underlie the neglectedness analysis suggest. It is also the largest share of any item in the US and far larger than the total global philanthropic spending for key neglected technologies such as negative emissions tech (25 million) and CCS or advanced nuclear (not even having their own positions, buried under clean electricity, but this will be heavily focused on renewables).

Importantly, this does not even include individual giving -- the major component of climate philanthropy -- which is likely tilting more towards grassroots activism and mainstream green solutions than elite advocacy for unpopular but critical solutions such as CATF’s. We discuss this more and why this makes it unlikely that grassroots activism is neglected in our report, quote from here (quoting in full as this is from a long report no one reads, but contains lots of material relevant here):

“According to this analysis, in the 2015-2019 period, about 100 million have been spent on public engagement in the US per year, more than a quarter of the climate philanthropic spending by foundations in the US in total. What is more, Jeff Bezos -- now the largest climate philanthropist in the world -- has focused his first round of grants on well-known Big Green groups that have a long history of raising awareness of the climate challenge, probably making that “public engagement” bucket significantly larger in future iterations of the ClimateWorks report.

Beyond philanthropy, the largest environmental NGOs have hundreds of thousands of members and even relatively new grassroots movements, such as Sunrise, have volunteers in the 10,000s, making environmental NGOs and grassroots a major political force.

At the same time, global philanthropic support for decarbonising sectors that are usually considered among the hardest to decarbonise -- transport and industry -- is less than that USD $75 million.12 Carbon dioxide removal, the technology considered most in need of additional innovation policy support, received only USD $25 million in global philanthropic support. These numbers do not allow differentiating by type of philanthropy so only a subset of these overall numbers will be focused on advocacy increasing overall societal resource allocation to these approaches; in other words these numbers are an overestimate for the type of advocacy work we are interested in assessing.

We tend to think that this presents an imbalance, given the large value of improving the allocation of public funds towards neglected technologies providing a strong proposition for advocacy. But, of course, increasing the pie is also critical and the imbalance proposition is, ultimately, a fairly hard-to-test hypothesis and almost philosophical question (we will attempt to gain some traction on this in 2021).”

Note that, while this states some uncertainty about assessing neglect, this was published before I had a chance to look in detail at the trajectory of Sunrise and progressive climate activism -- given Alex’s numbers and analysis, I would be fairly confident (> 80%) at this point that grassroots activism right now is significantly less neglected than CATF-style work.

5. Neglect is only a proxy, but it informs a prior on the usefulness of funding margins for which the TSM analysis provides little update

As an EA working on climate, I am very sympathetic to the argument that neglectedness is a proxy and can lead astray.

But in Dan’s comment above this mostly reads like shifting goal-posts, the argument for neglect was justified with financing numbers that were outdated. Even if they are just a proxy, the fact that those numbers are importantly outdated and wrong should lead to changes in the analysis (an advantage of quantitative analysis).

While it is true that the funding for CATF has increased strongly over the last few years, it has not increased by orders of magnitude. More importantly, the reason it has increased has been -- to a large part -- because of the EA community starting with John’s 2018 report and, as such, is not reflective of a wider societal trend towards the CATF-style of advocacy leading us to expect everything of that style to be funded (And, CATF has increased its geographic reach thereby extending productive funding margins (because funding margins for advocacy are a function of the goodness of improving resource allocation / policy in a jurisdiction).

Indeed, it is more likely that the opposite is the case.

After the failure of cap-and-trade in 2010 it became conventional wisdom in climate philanthropy that more grassroots activism was needed, as also stated in Giving Green’s Deep Dive.

While it is not clear that this belief was true -- the failure of Waxman-Markey in 2010 was severely over-determined with lots of plausible interpretations -- this belief had causal force.

It is thus no accident that attention to public engagement funding has increased so strongly. In other words, in climate philanthropy, the grassroots wing has been winning rather than being most neglected.

In addition, Sunrise has emerged as an important flank of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party and the Democrats having outraised Republicans on much smaller average donations (more grassroot-y) in the recent elections.

As such, saying Sunrise is neglected is -- absent more current numbers that make the case -- similar to saying “Jon Ossoff’s Senate campaign is neglected” in late December after he raised more than 100 million USD. Sure, it is conceivable that there are things that Jon Ossoff would have funded with marginal donations that would have been highly effective, but we should be skeptical of such arguments precisely because a reasonably strategic actor that is not obviously funding-constrained will have a funding margin with relatively low-value activities.

In that way, neglectedness serves as a prior on the expected goodness of the funding margin. That prior can be updated by additional considerations that make something in a non-neglected field good, but this requires strong arguments. In a field that is financially well-resourced or easy to be well-resourced (when you have 10,000 volunteers and you have lots of high-value funding gaps at the margin, some more of those volunteers should focus on fundraising), it would be surprising if there are great marginal funding opportunities.

Of course there could be.

Indeed, the argument that John Halstead, Hauke Hillebrandt, and myself have been making in various forms over the last years is that there are such opportunities within climate -- namely, around supporting (1) neglected technologies and (2) a neglected part of technology support, support for innovation, via (3) decision-maker focused advocacy that improves how the vast resources allocated to climate are better spent.

The long and short of it is that there are systematically neglected technologies and many ideological and other reasons for this neglect, that innovation is generally neglected for reasons of various market failures, as well as ideological factors, etc. In other words, there is a systematic argument for why the CATF/C180/ITIF/TP style of advocacy should be really high impact despite climate not being neglected overall.

But there is no parallel argument made -- to my knowledge -- for why in case of Sunrise we should move away from the prior that something that has increased 40x-fold in funding over the last years and has captured the public imagination and support of an entire wing of a major US political party, would have great room for funding left.

Dan’s response to this concern raised by Alex is this:

“I think that there is very little effective climate activism happening out there, and there’s huge room for effective growth.”

Essentially, the only argument for why it should be particularly high impact to give to TSM right now is a claim about the ineffectiveness of current climate activism and a proclaimed large effective growth potential, without any justification that spending more money on climate activism will lead to more effective climate activism.

With this level of unspecific justification, almost anything can be declared a highly effective funding margin to fill.

REASONS TO BE UNSURE ABOUT THE SIGN OF IMPACT

6. The positive marginal case is pretty unclear

It is not clear how we would evaluate success of the Sunrise Movement -- whether this would be passing the Green New Deal or whether it is just generally shifting the Overton window of climate policy. The more charitable interpretation is probably to say “Sunrise shifts the overton window of climate policy” given that the Green New Deal is mostly a symbolic policy without real prospects of passing.

This is the approach we took in our Biden report -- conceptualizing grassroots movements as “increasing the pie” (the opportunities, not only strictly budgets) and orgs such as CATF focused on improving how the pie is utilized for maximal decarbonization benefits. Quoting here (emphasis new):

“But, while it is difficult to make a statement about the relative balance [between pie-increasing and pie-improving], we think it is clear that now that we have a very climate-friendly administration -- likely under divided government, if not with razor-thin majority [this was published in November] -- the value of policy advocacy to improve how the attention to climate is spent strongly increases, easily by a factor of 4 or more (taking a conservative average from the advocacy value of the next four years, based on our timing analysis above) compared to a second Trump term.

At the same time, it is difficult to see how the value of funding advocacy focused on increasing the pie could have increased by the same amount based on the outcomes of the election.

Indeed, insofar as mass mobilization and climate grassroots activism are strongly tied to the Democratic party and making Democrats more ambitious on climate, it seems likely that the value of this advocacy has decreased due to the relative underperformance of Democrats in Congressional races and the likely less Democratic-leaning environment in the midterm elections.13

On balance, we think that the election directionally shifts the balance towards advocacy to improve resource allocation and policy rather than advocacy focused on increasing overall resource allocation (increasing the pie), so we feel more certain in the relative prioritisation of this kind of advocacy in our philanthropy.”

Now that we have more information with the Georgia win and the laser-thin Democratic majority we can say a bit more than this directional shift, about the marginal impact of Sunrise in this moment.

We are now in a situation where Biden has declared climate as one of his top four priorities, where the pivot in the Senate is Joe Manchin, a West Virginia Democrat, who really likes CCS and really doesn’t like the Green New Deal.

In this situation, any passage of bills requires support from very conservative Democrats and, if not all Democrats are on board, of some Republicans (even for reconciliation, filibuster-proof climate policy is out of the question anyway).

Unless Sunrise has a great way to influence fairly conservative Senators, which is not what they have focused on to do to date, it seems a bit unclear what good a marginally stronger TSM at this moment accomplishes.

To be sure, the pressure of TSM and others is very valuable, in principle. But now that climate is on top of the agenda of things and we face a pretty thin majority situation for the party aligned with Sunrise, is it really plausible that making this movement marginally stronger is very important?

While one could make that case, e.g. that a stronger TSM is needed now because pressure on relatively progressive legislators is still a bottleneck, or because Biden will forget about climate if we do not further strengthen TSM, this does not seem very plausible.

While arguments have been made that TSM is sitting at the table with the Biden administration and that this is a reason to fund them, this kind of reasoning would require confidence that TSM directs Biden’s climate action in the best direction.

TSM is a grassroots organization specialized in raising attention to climate, not in advising on effective climate policy. That is something that CATF et al. specialize in. Furthermore, funding the Sunrise Movement Education Fund would not directly influence the already existing representation of TSM at the table.

When stating confidently that giving to TSM right now is highly impactful, it would be good to clarify what the exact path to impact is.

The broad description in the theory of change of “climate change becomes a government priority” and “climate bills that reduce emissions get passed” is not very clear, and -- in particular -- does not refer to a marginal case, that more is needed to make this as likely as TSM can make those outcomes.

Just to be clear, I am not suggesting that the answer to all of these questions is negative for TSM. I am just pointing out questions that would need analysis to make claims of high impact more credible.

7. Ways in which Sunrise could be negative at the current margin

Indeed, there are many ways in which existing or additional support for TSM can contribute to negative outcomes:

The list could go on.

Again, my point is not that these are all damning concerns but that these large uncertainties about the severity and probability of negative effects of marginal TSM donations pushes the estimate downwards.

8. Ways in which Sunrise could be negative (in general)

More generally, beyond the current marginal case, there are other more general concerns.

Alex makes valuable points about how Sunrise could have negative impacts and I have mentioned some of them as well before (e.g. in my talk at EAGx Virtual last June) and in other contexts. Dan adds some additional ones.

So, there are at least the following five pathways in which Sunrise could be negative:

A. Sunrise further polarizes the US climate debate thereby reducing the chance of useful climate legislation to become reality.

B. Sunrise promotes a view of the climate challenge that reduces the support for effective solutions

From spending the last ten years studying and working in climate policy, I can say with confidence that both of those lines of concern are major considerations, major ways in which -- in the past -- climate activism has been harmful and major worries of very serious climate analysts about current grassroots climate activism.

These are serious concerns that warrant thorough investigation rather than a false equivalence reply claiming there is a similarly serious concern with CATF and similar orgs.

Of course these concerns are not all there is, there is a positive case, too. But those concerns need to be integrated when forming a view on TSM as a funding opportunity.

INTEGRATING CONCERNS

How does this all fit together?

Size of impact

The assumption in the TSM analysis is that there is something transformative / unique / high value in TSM that only TSM or grassroots activism can deliver. As I argued in the “Some misconceptions about CATF” section above, this claim does not seem well-supported because both technological change driven through incremental policies and climate laws could be transformative. There is no reason to assume that TSM > CATF on this at this point. One could try to model this.

Low marginal additionality (neglectedness)

Because of the explosion of attention to TSM and the increase in TSM and general grassroots funding, additional dollars change relatively little about TSM’s activities (relatively speaking), are more likely to not be counterfactually additional (if funding goals are just met in any case), and are likely to fill activities that are relatively far from the most valuable ones.

Sign of impact

If one does not study those concerns about direction in detail and convincingly shows that these are not applicable to marginal TSM funding, then what Alex states is totally justified -- there is uncertainty about the sign of the impact.

Crucially, that uncertainty is about the expected mean, not particular outcomes (something that, I think, Dan misunderstood in his reply to Alex).

Even if that uncertainty does not move us into negative territory with regards to the mean, it pushes the expected value downwards. There are just many plausible futures where marginal TSM funding is negative and that pushes the expected value towards zero or into negative territory.

If one combines these three factors what emerges is a funding opportunity where we should expect a low expected value; whether we fund or not makes little difference and it is relatively unclear whether it will have a positive impact.

It would be pretty surprising if that was anywhere close in marginal impact than giving to CATF.

It could, of course, be the case, though. But to state that as likely would require a lot more research and, with current information, it does not seem warranted.

No worries about the delay, now it's my term to apologise as it's been a while on my side too! I am finding this quite fascinating and informative so I really appreciate you taking the time to write such detailed and thorough comments. I also wanted to thank you for your work at FP as everything I've read from FP regarding climate has been extremely rigorous and interesting.

1. Differences between TSM and XR: These points make sense so thank you for the explanation. It seems like the main concern you have about TSM is their partisanship and allegiance with ... (read more)