Two prominent economists and writers, Chris Blattman and Noah Smith, both recently and independently published blog posts on the likelihood of war between China and the US over Taiwan. They are not optimistic. Both seem to think that war is relatively likely. Unfortunately, neither offers a quantitative forecast, but I think it's interesting and useful for serious researchers to write about their views on such important questions.

Chris's post is called "The prospects for war with China: Why I see a serious chance of World War III in the next decade". Noah's is "Why I think an invasion of Taiwan probably means WW3". They complement each other well, with Chris's post arguing that war seems likely and Noah's post arguing that the US would probably get involved in the event of a war.

Chris's post on why bargaining may break down

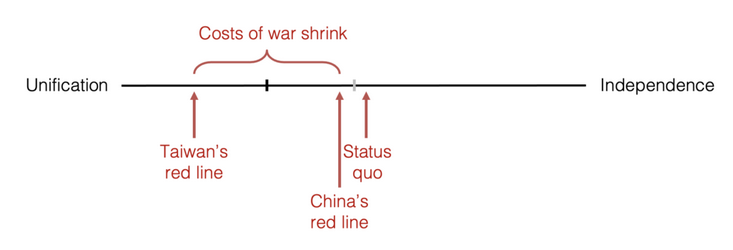

Chris applies the bargaining framework he used throughout his book Why We Fight to show why war is becoming more likely as China continues to grow its economy and strengthen its military. Eventually, the status quo of de facto Taiwanese independence will slip outside of its "compromise range". When this happens, Chinese leaders may decide going to war to try to bring about a different outcome may be preferable, despite the costs.

Still, war is risky and negative-sum. A negotiated settlement should, in principle, be preferable for all parties. Chris suggests that negotiations may fail because ideological principles (e.g. democracy vs autocracy) can be non-negotiable, China's crackdown on Hong Kong harmed its reputation for sticking to negotiated settlements, and Xi Jinping is increasingly unchecked and isolated in his leadership.

Noah's post on why the US would probably get drawn into the war

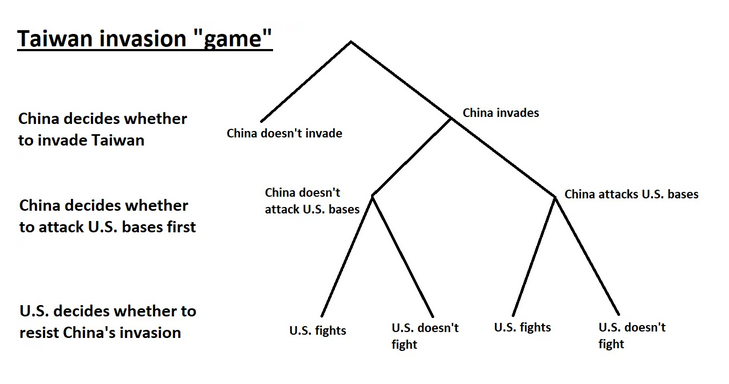

Noah also applies economic thinking to inform his geopolitical analysis, using game theory to predict which war scenarios seem more likely based on the interests of the actors involved.

Noah considers about how important various factors, like national pride, reputation, and military costs, seem to Chinese and American leaders. He then tries to weigh up how important these costs and benefits seem relative to each other to work out the payoffs to each actor is in each of the four possible outcomes of the game. Then he assigns probabilities to work out expected payoffs, and figures out the equilibrium through backwards induction. Long story short, the equilibrium solution under these assumptions is for China to invade and attack the US to maximize its chances of victory, nearly assuring the outbreak of a major great power war.

Of course, there are many ways this analysis could be wrong, and Noah touches on them at the end of the post. For example, given escalation risk, perhaps the payoffs in any "US fights" outcome are hugely negative for both parties, making it very unlikely that they would both choose to fight. Or, perhaps losing a fight over Taiwan would be so negative for China's leadership that it's just too risky (the expected payoff is negative) to undertake. Or, perhaps the leadership of each country is misinformed about the likelihood of each outcome, leading to miscalculation, bad decision-making, and a sub-optimal (i.e. very costly) outcome.

Why they're worth reading

Both posts analyze the US-China-Taiwan situation from a specific, economic framework. How insightful you find them will depend somewhat on how much resemblance you think this kind of rational analysis of weighing expected costs and benefits bears to actual foreign policy decision-making. But I think it's great to see serious thinkers trying to make progress on important questions like "Will World War III happen?" in public.

Thanks for sharing, Stephen. Useful resources! Still in the process of listening to Chris Blattman's book "Why We fight". Enjoying it so far.

If anyone is interested to think about the implications of a Taiwan invasion on the compute supply chain (TSMC etc.), PM me.