In March 2020, I wondered what I’d do if - hypothetically - I continued to subscribe to longtermism but stopped believing that the top longtermist priority should be reducing existential risk. That then got me thinking more broadly about what cruxes lead me to focus on existential risk, longtermism, or anything other than self-interest in the first place, and what I’d do if I became much more doubtful of each crux.[1]

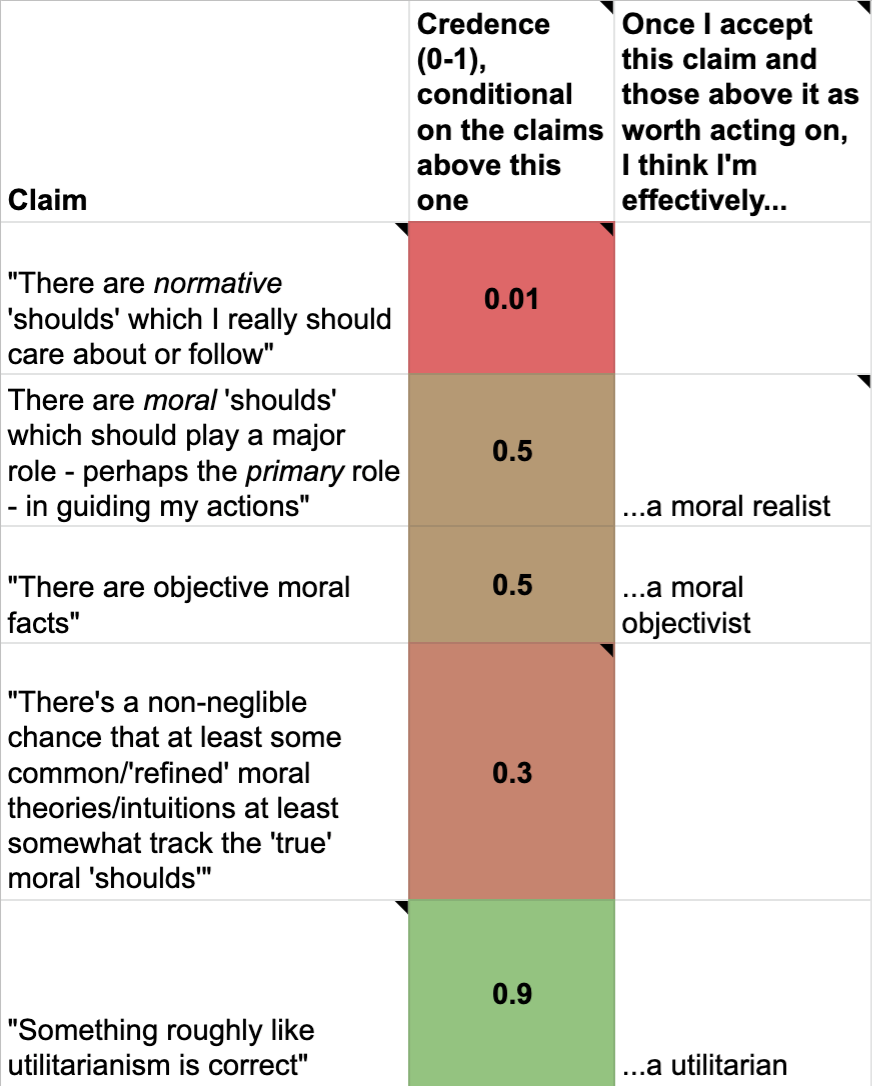

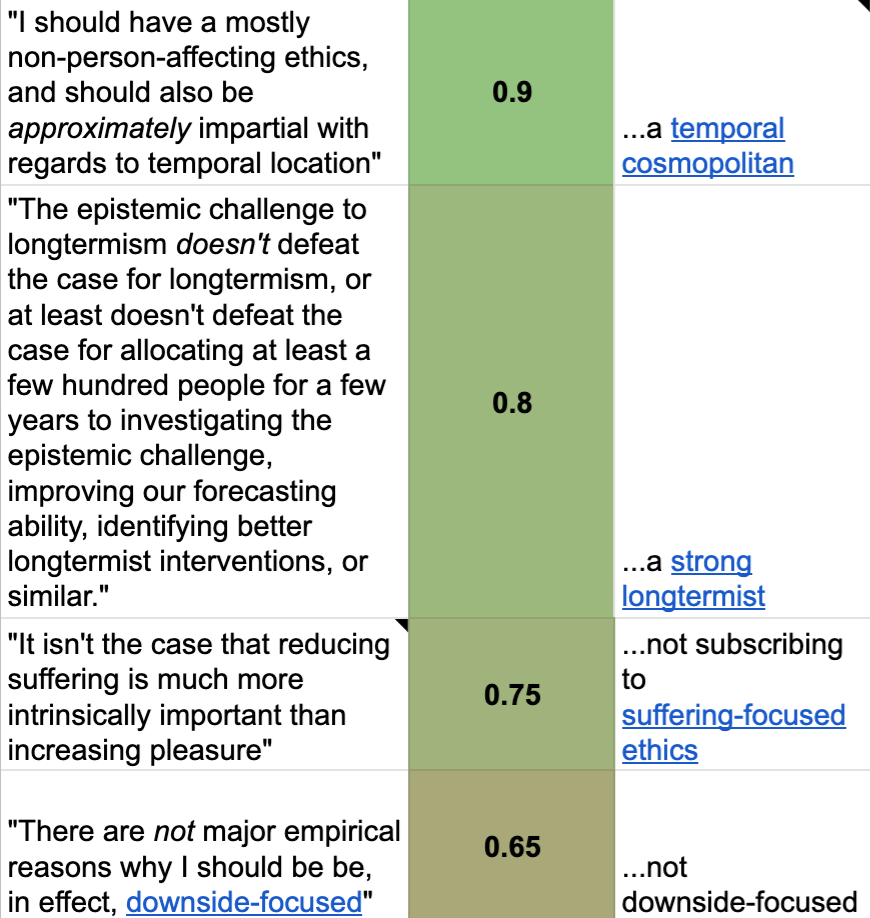

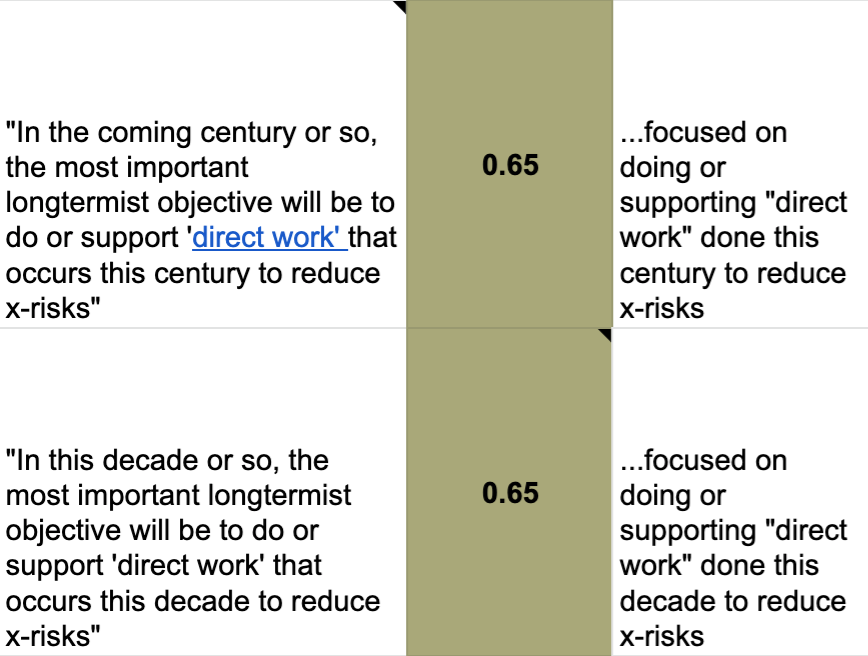

I made a spreadsheet to try to capture my thinking on those points, the key columns of which are reproduced below.

Note that:

- It might be interesting for people to assign their own credences to these cruxes, and/or to come up with their own sets of cruxes for their current plans and priorities, and perhaps comment about these things below.

- If so, you might want to avoid reading my credences for now, to avoid being anchored.

- I was just aiming to honestly convey my personal cruxes; I’m not aiming to convince people to share my beliefs or my way of framing things.

- If I was making this spreadsheet from scratch today, I might’ve framed things differently or provided different numbers.

- As it was, when I re-discovered this spreadsheet in 2021, I just lightly edited it, tweaked some credences, added one crux (regarding the epistemic challenge to longtermism), and wrote this accompanying post.

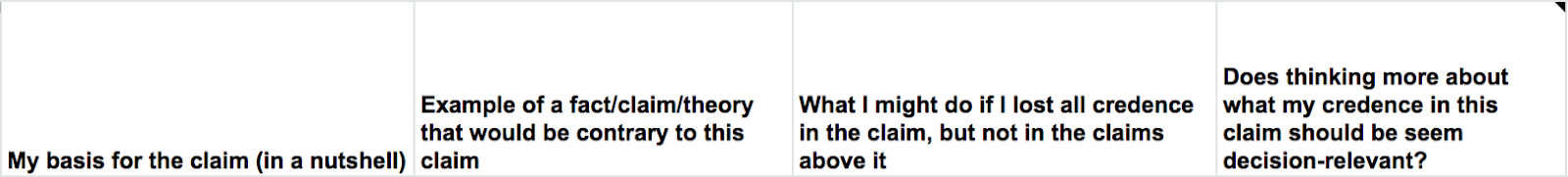

The key columns from the spreadsheet

See the spreadsheet itself for links, clarifications, and the following additional columns:

Disclaimers and clarifications

- All of my framings, credences, rationales, etc. should be taken as quite tentative.

- The first four of the above claims might use terms/concepts in a nonstandard or controversial way.

- I’m not an expert in metaethics, and I feel quite deeply confused about the area.

- Though I did try to work out and write up what I think about the area in my sequence on moral uncertainty and in comments on Lukas Gloor's sequence on moral anti-realism.

- I’m not an expert in metaethics, and I feel quite deeply confused about the area.

- This spreadsheet captures just one line of argument that could lead to the conclusion that, in general, people should in some way do/support “direct work” done this decade to reduce existential risks. It does not capture:

- Other lines of argument for that conclusion

- Perhaps most significantly, as noted in the spreadsheet, it seems plausible that my behaviours would stay pretty similar if I lost all credence in the first four claims

- Other lines of argument against that conclusion

- The comparative advantages particular people have

- Which specific x-risks one should focus on

- E.g., extinction due to biorisk vs unrecoverable dystopia due to AI

- See also

- Which specific interventions one should focus on

- Other lines of argument for that conclusion

- This spreadsheet implicitly makes various “background assumptions”.

- E.g., that inductive reasoning and Bayesian updating are good ideas

- E.g., that we're not in a simulation or that, if we are, it doesn't make a massive difference to what we should do

- For a counterpoint to that assumption, see this post

- I’m not necessarily actually confident in all of these assumptions

- If you found it crazy to see me assign explicit probabilities to those sorts of claims, you may be interested in this post on arguments for and against using explicit probabilities.

Further reading

If you found this interesting, you might also appreciate:

- Brian Tomasik’s "Summary of My Beliefs and Values on Big Questions"

- Crucial questions for longtermists

- In a sense, this picks up where my “Personal cruxes” spreadsheet leaves off.

- Ben Pace's "A model I use when making plans to reduce AI x-risk"

I made this spreadsheet and post in a personal capacity, and it doesn't necessarily represent the views of any of my employers.

My thanks to Janique Behman for comments on an earlier version of this post.

Footnotes

[1] In March 2020, I was in an especially at-risk category for philosophically musing into a spreadsheet, given that I’d recently:

- Transitioned from high school teaching to existential risk research

- Read the posts My personal cruxes for working on AI safety and The Values-to-Actions Decision Chain

- Had multiple late-night conversations about moral realism over vegan pizza at the EA Hotel (when in Rome…)

tl;dr

I'll split that into three comments.

But I should note that these comments focus on what I think is true, not necessarily what I think it's useful for everyone to think about. There are some people for whom thinking about this stuff just won't be worth the time, or might be overly bad for their motivation or happiness.

1. Where I agree with your comment

Am I correct in thinking that you mean you worry how much conducting this sort of exercise might affect anyone who does so, in the sense that it'll tend to overly strongly make them think they should reduce their confidence in their bottom-line conclusions and actions? (Because they're forced to look at and multiply one, single, conjunctive set of claims, without considering the things you mention?)[1]

If so, I think I sort-of agree, and that was the main reason I consider never posting this. I also agree that each of the things you point to as potentially "explaining the discrepancy" can matter. As I note in a reply to Max Daniel above:

And as I note in various other replies here and in the spreadsheet itself, it's often not obvious that a particular "crux" actually is required to support my current behaviours. E.g., here's what I say in the spreadsheet I'd do if I lost all my credence in the 2nd claim:

This is why the post now says:

And this is also why I didn't include in this post itself my "Very naive calculation of what my credence "should be" in this particular line of argument" - I just left that in the spreadsheet, so people will only see that if they actually go to where the details can be found. And in my note there, I say:

[1] Or you might've meant other things by the "it", "you", and "bias" here. E.g., you might've meant "I worry how much seeing this post might bias people who see it", or "I worry how much seeing this post or conducting this exercise might cause a bias towards anchoring on one's initial probabilities."