If you want to communicate AI risks in a way that increases concern,[1] our new study says you should probably use vivid stories, ideally with identifiable victims.

Tabi Ward led this project as her honours thesis. In the study, we wrote[2] short stories about different AI risks like facial recognition bias, deepfakes, harmful chatbots, and design of chemical weapons. For each risk, we created two versions: one focusing on an individual victim, the other describing the scope of the problem with statistics.

We had 1,794 participants from the US, UK and Australia[3] read one of the stories, measuring their concern about AI risks before and after. Reading any of the stories increased concern. But, the ones with identifiable individual victims increased concern significantly more than the statistical ones.

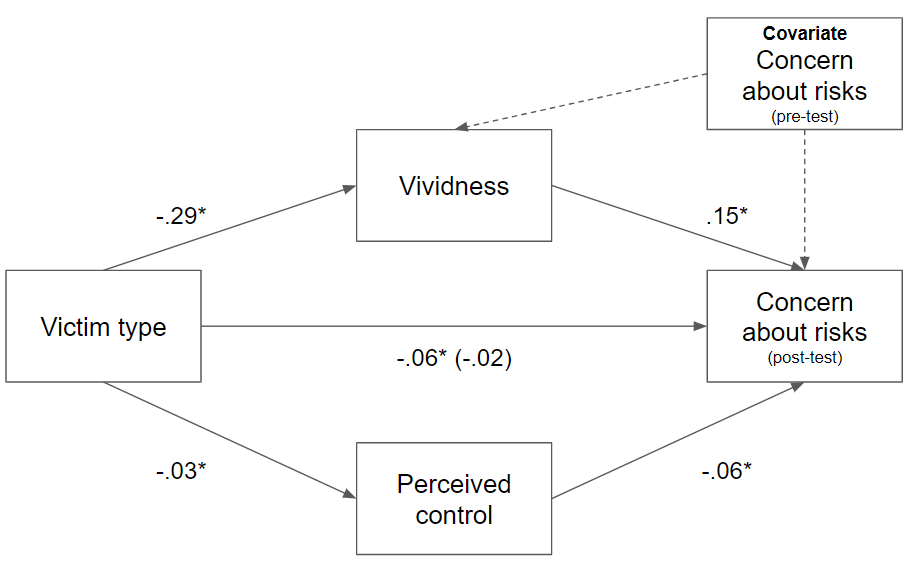

Why? The individual victim stories were rated as more vivid by participants. A mediation analysis found the effect of identifiable victims on concern was explained by the vividness of the stories:

This finding aligns with prior research on "compassion fade" and the "identifiable victim effect": people tend to have stronger emotional responses and helping intentions towards a single individual in need than towards larger numbers or statistics. Our study extends this to the domain of risk perception.

Communicating about the harms experienced by identifiable victims is a particular challenge for existential risks. These AI risks are defined by their scale and their 'statistical victim' nature: they could affect billions, but have not yet occurred. Nevertheless, those trying to draw attention to concerns should try to make the risks vivid. The most compelling narrative was one with an identifiable victim of an AI-designed 'nerve agent' was the most compelling narrative, but was a hypothetical future story (not a real one from a news report, like the others).

This might influence the way people communicate about AI. For example, when people are trying to increase concern, it might be harder for a reader to imagine how the following request from an AI is dangerous:

Take this strawberry, and make me another strawberry that's identical to this strawberry down to the cellular level, but not necessarily the atomic level.

Instead, our results would suggest it might be more potent to use compelling analogies that are easier to imagine:

Since these AI systems can do human-level economic work, they can probably be used to make more money and buy or rent more hardware, which could quickly lead to a "population" [of AIs] of billions or more.

The takeaway: if you're trying to highlight the potential risks of AI development, vivid stories may be an effective approach, particularly if they put a human face to the risks. It suggests the behavioural economics of risk communication seems to apply to AI risks.

- ^

Obviously this can go too far, as the mini-series Chernobyl may have done for nuclear power. We're not making judgements about whether or not increasing concern is 'good', but pointing to effects that influence perception.

- ^

We used ChatGPT 4 (June 2023) to generate initial versions of stories from prompts, then edited for consistency. In social science research, it's important that these stories (called 'vignettes') are carefully controlled for length, tone, etc - everything except the key variable under investigation. View all the stories on our Open Science Framework repository.

- ^

These were members of the general public recruited through Prolific, not necessarily representative of key decision-makers for AI safety. However, we have found anecdotally that public beliefs about AI risks and expectations can influence decision-makers.

Great job!

Did you use causal mediation analysis, and can you share the data?

I want to note that the strawberry example wasn’t used to increase the concern, it was used to illustrate the difficulty of a technical problem deep into the conversation.

I encourage people to communicate in vivid ways while being technically valid and creating correct intuitions about the problem. The concern about risks might be a good proxy if you’re sure people understand something true about the world, but it’s not a good target without that constraint.

Yes all data and code are on the osf, but to my chagrin they’re in spss. Yes good observation re the strawberry, and the imprecision around the outcome.