Some recent virology and aerosol science research[1][2] might support an ever-so-slightly higher real cost of atmospheric CO2 and, more practically, an even stronger case for ventilation indoors with respect to biosecurity and pandemics.

Basically, ambient CO2 concentrations have a direct effect on the duration that aerosolized droplets containing SARS-COV2, and probably some other pH-sensitive viruses, remain infectious. This is due to the presence of bicarbonate in the aerosol, which leaves the droplet as CO2. Consider the following equation[2] and then recall or review Le Chetalier's principle from chemistry.

H+(aq)+HCO−(aq)3↔H2CO3(aq)↔CO2(g)+H2O(1)

More CO2 in the surrounding air shifts the equilibrium to reduce the net loss of CO2 from the aerosol, slowing the rate at which the pH increases, thereby slowing the rate at which the aerosol loses its infectivity (this virus doesn't do well in a high-pH environment).

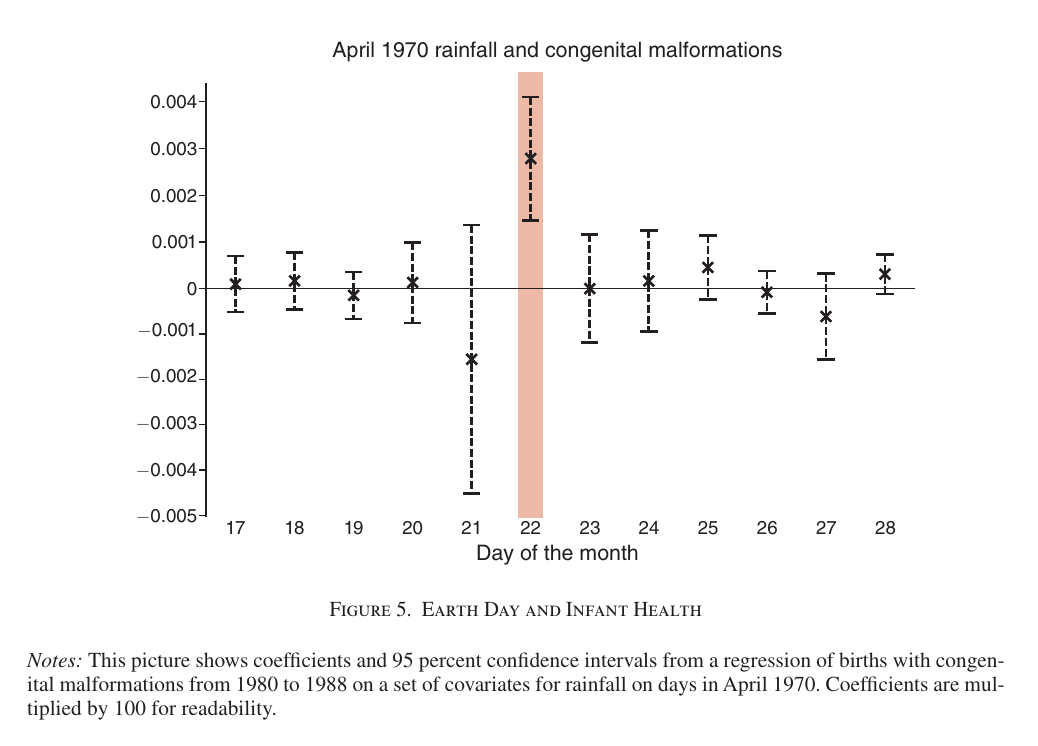

For getting an idea of the magnitude of the effect, Figure 2B[2] and its caption are simple and illustrative: "The effect that an elevated concentration of CO2 has on the decay profile of the Delta VOC and original strain of SARS-CoV-2 at 90% RH. Inset is simply a zoom-in of the first 5 min of the x-axis. Elevating the [CO2(g)] results in a significant difference in overall decay assessed using a one-sided, two-sample equal variance, t-test (n = 188 (independent samples)) of the Delta VOC from 2 min onward, where the significance (p-value) was 0.007, 0.027, 0.020 and 0.005 for 2, 5, 10 and 40 min, respectively." Other figures show differing results for other variants which seem to have different levels of pH-sensitivity.

![The effect that an elevated concentration of CO2 has on the decay profile of the Delta VOC and original strain of SARS-CoV-2 at 90% RH. Inset is simply a zoom-in of the first 5 min of the x-axis. Elevating the [CO2(g)] results in a significant difference in overall decay assessed using a one-sided, two-sample equal variance, t-test (n = 188 (independent samples)) of the Delta VOC from 2 min onward, where the significance (p-value) was 0.007, 0.027, 0.020 and 0.005 for 2, 5, 10 and 40 min, respectively.](https://res.cloudinary.com/cea/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto/v1/mirroredImages/n6aBPjJ9XXbaGphys/ra6e08sz3aynreeqrbpb)

This acts in addition to - and is not to be confused with - the generally more important (as far as I know) fact that indoor CO2 readings serve as a proxy for proportion of rebreathed air and thus aerosol concentrations in the absence of active air filtration.

An interesting research direction would be to look at likely future pathogens and try to make predictions about how likely they are to be pH-sensitive in a way that would make them extra vulnerable to better indoor ventilation. Apart from that, there's no big call to action here other than the afformentioned small update to your mental model of indoor ventilation.

I think there hasn't been enough research on iota-carageenan nasal sprays for prevention of viral infection for things more infectious than common colds. There was one study aimed at COVID-19 prophylaxis with it in hospital workers which was really promising: "The incidence of COVID-19 differs significantly between subjects receiving the nasal spray with I-C (2 of 196 [1.0%]) and those receiving placebo (10 of 198 [5.0%]). Relative risk reduction: 79.8% (95% CI 5.3 to 95.4; p=0.03). Absolute risk reduction: 4% (95% CI 0.6 to 7.4)."

There was one clinical trial afterwards which set out to test the same thing but I can't tell what's going on with it now, the last update was posted over a year ago. So we have one study which looks great but could be a fluke, and there's no replication in sight.

The good thing about carageenan-based products is that they're likely to be safe, since they're extensively studied due to their use as food additives and in other things. From Wikipedia: "Carrageenans or carrageenins [...] are a family of natural linear sulfated polysaccharides. [...] Carrageenans are widely used in the food industry, for their gelling, thickening, and stabilizing properties." See this section of the article for more.

If it really does work for COVID and is replicated with existing variants, that's already a huge public health win - there's still a large amount of disability, death and suffering coming from it. With respect to influenza, theres's some evidence for efficacy in mice and the authors of that paper say that it "should be tested for prevention and treatment of influenza A in clinical trials in humans."

If it has broad-spectrum antiviral properties then it's also a potential tool for future pandemics. Finally, it's generic and not patented so you'd expect a lack of research funding for it relative to pharmaceutical drugs.

Some recent virology and aerosol science research[1][2] might support an ever-so-slightly higher real cost of atmospheric CO2 and, more practically, an even stronger case for ventilation indoors with respect to biosecurity and pandemics.

Basically, ambient CO2 concentrations have a direct effect on the duration that aerosolized droplets containing SARS-COV2, and probably some other pH-sensitive viruses, remain infectious. This is due to the presence of bicarbonate in the aerosol, which leaves the droplet as CO2. Consider the following equation[2] and then recall or review Le Chetalier's principle from chemistry.

More CO2 in the surrounding air shifts the equilibrium to reduce the net loss of CO2 from the aerosol, slowing the rate at which the pH increases, thereby slowing the rate at which the aerosol loses its infectivity (this virus doesn't do well in a high-pH environment).

For getting an idea of the magnitude of the effect, Figure 2B[2] and its caption are simple and illustrative: "The effect that an elevated concentration of CO2 has on the decay profile of the Delta VOC and original strain of SARS-CoV-2 at 90% RH. Inset is simply a zoom-in of the first 5 min of the x-axis. Elevating the [CO2(g)] results in a significant difference in overall decay assessed using a one-sided, two-sample equal variance, t-test (n = 188 (independent samples)) of the Delta VOC from 2 min onward, where the significance (p-value) was 0.007, 0.027, 0.020 and 0.005 for 2, 5, 10 and 40 min, respectively." Other figures show differing results for other variants which seem to have different levels of pH-sensitivity.

This acts in addition to - and is not to be confused with - the generally more important (as far as I know) fact that indoor CO2 readings serve as a proxy for proportion of rebreathed air and thus aerosol concentrations in the absence of active air filtration.

An interesting research direction would be to look at likely future pathogens and try to make predictions about how likely they are to be pH-sensitive in a way that would make them extra vulnerable to better indoor ventilation. Apart from that, there's no big call to action here other than the afformentioned small update to your mental model of indoor ventilation.

The dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity with changes in aerosol microenvironment

Ambient carbon dioxide concentration correlates with SARS-CoV-2 aerostability and infection risk