In the past twenty years, animal advocacy groups have put an enormous amount of effort into convincing people to be vegetarian. However, polls suggest that the percentage of the population that’s vegetarian has stayed basically flat since 1999. In short, we’re basically treading water: for every new vegetarian we convince, someone else quits. As you’d expect given this fact, more than four-fifths of vegans and vegetarians eventually abandon their diets.

Of course, an ex-vegetarian isn’t the same as a lifelong omnivore. They might eat less meat because they’ve discovered new favorite recipes, and they might have more knowledge of and sympathy for animal issues. (Conversely, of course, they might have been so alienated from the vegetarian and animal advocacy community that they’re more bitter and angry about it than the average omnivore.) But if we’re trying to reduce animal consumption, this is a bad sign!

Fortunately, we’re only addressing half the problem. There are lots of people trying to make people be vegetarian, but there’s far less effort put into getting them to stay vegetarian. While there are some programs along these lines, they tend (in my experience) to not be very elaborate or well-funded, particularly compared to vegan outreach. As far as I’m aware, no one has run a study of the effectiveness of various methods of keeping people vegetarian.

This is sad, because there are a priori reasons to believe that keeping people vegetarian would be easier than making them vegetarian in the first place. Vegetarians generally want to stay vegetarian, so they’re eager to listen to your information—unlike omnivores, who have to be convinced. It seems like there’s low-hanging fruit in vegetarian retention: for example, even today, many vegans don’t know about the importance of taking a B12 supplement, which means that they risk health problems that they’ll treat by going back to eating animal products.

According to a qualitative Faunalytics study, the most common reasons that people quit being vegetarian are:

- Disliked/bored with food, wanted variety, wanted meat

- Nutrient concerns or deficiencies (perceived or actual)

- Did not enjoy it, tired of it, unsatisfied, or bored

- Family, relationship, household, or children

- Felt fatigued, lightheaded, weak, or unhealthy

Many of these seem potentially addressable. We could recommed people more delicious food, show them how to substitute meat in their diets (for example, with alternate sources of the umami taste), teach them more about vegetarian nutrition, and help them to find social support. It may help to develop standard advice for common situations, such as being vegetarian while cooking for a family that is not vegetarian, and then promoting them widely. Many animal advocacy organizations are doing something along these lines to begin with, but few are doing it in a systematic way.

Vegetarian retention also seems to me to be easier to study than convincing people to become vegetarian. The hardest part of conducting a study of a method to convince people to become vegetarian is followup: how do you track down the same person you showed a video to six months later to discover whether they reduced their meat consumption? However, vegetarian retention studies can be done using the mailing lists that animal advocacy organizations already have. You’d still get attrition, of course, but the attrition is potentially much lower.

Of course, it might turn out that vegetarian retention is legitimately extremely difficult. For example, maybe only some people can be healthfully fully vegetarian for reasons we don’t understand yet, and so most prospective vegetarians will quit. But that’s also valuable to know: it suggests that we should focus on better plant-based meat alternatives, more research into nutrition science, and encouraging people who can’t handle vegetarianism to be “reducetarian.”

In short, I think more animal advocacy organizations should do randomized controlled trials of promising techniques to improve retention rates for vegetarians, so that we have a strong evidence base for this potentially effective intervention.

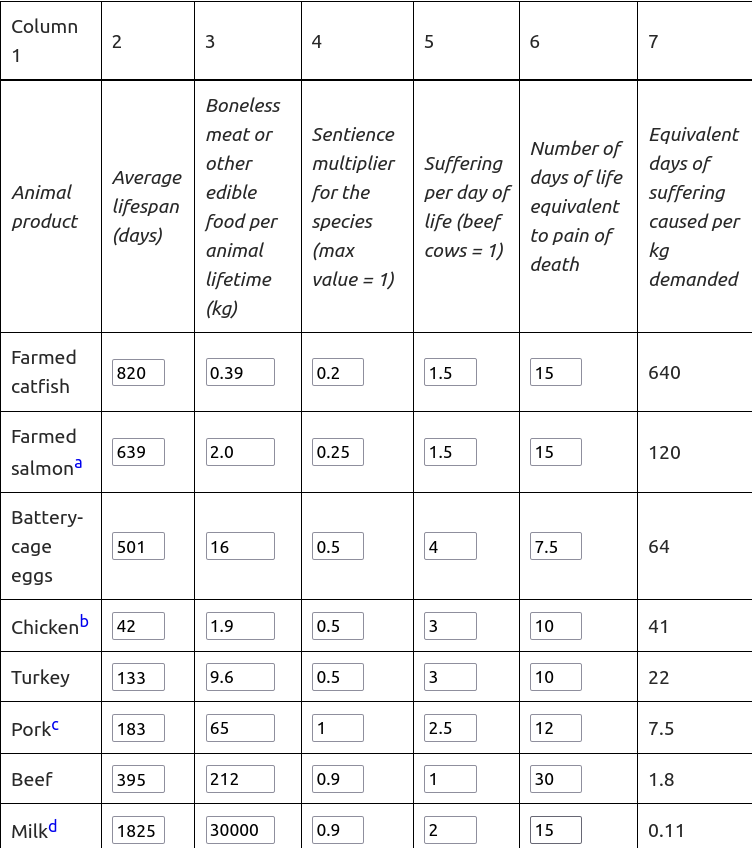

Vegetarians/vegans should consider promoting eating only beef/dairy as the only animal products they consume as a potential strategy to have people cause less suffering to livestock with a high retention rate. I suspect that the average person would be much more willing to give up most animal products while still consuming beef and dairy, compared to giving up meat entirely. Since cows are big, fewer animals are needed to produce a single unit of meat, compared to meat coming from smaller animals. Vitalik Buterin has argued that eating big animals as an animal welfare strategy could be 99% as good as veganism. Brian Tomasik also compiled this list of different animal products ranked by the amount of suffering they cause per kilogram, and beef and milk are at the bottom.

An objection people might make to this is that eating more beef could contribute to climate change, but I'm skeptical that the amount of additional suffering caused by climate change will exceed the amount of suffering reduced by having less factory farming. It could also be argued that habitat loss may reduce wild animal populations, which may reduce wild animal suffering by preventing wild animals by being born.

As a side note, there needs to be some sort of name for the philosophy of eating big animals to reduce livestock suffering described above. Sizeatarianism? Beefatarianism? Big-animal-atarianism? Sufferingatarianism?

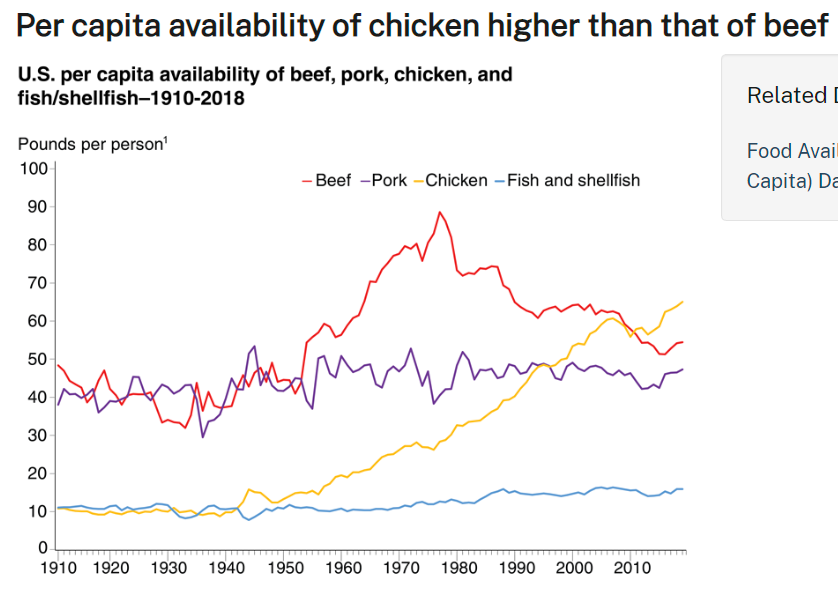

Extremely unfortunately, the idea that people's choices of animals is static, or that consumption within meat or eggs is fixed, is very much not true.

Below is a chart showing the stats for US animal consumption between chicken... (read more)