The failure rate is not 0

The base rate of failure for startups is not 0: Of the 6000 companies Y Combinator has funded, only ~16 are public. This is the wrong reference class for FTX at a $32b valuation, but even amongst extremely valuable companies, failures are not uncommon:

- WeWork had a peak valuation of $47b

- Theranos had a peak valuation of $10b

- Lucid Motors had a peak valuation of $90b

- Virgin Galactic had a peak valuation of $14b

- Jull had a peak valuation of $38b

- Bolt had a peak valuation of $11b

- Magic Leap had a peak valuation of $13b

That is only a handful of cases, but the reference class for startups worth over $10b is also pretty small. Maybe 45 private companies and another ~100 that have gone public. I'm playing pretty fast and loose here because the exact number isn't important, the odds of failure are not super high, but they are considerably higher than 0.

The base rate of failure for crypto exchanges and hedge funds is not 0: Three Arrows Capital was managing $10b, Mt. Gox was "handling over 70% of all bitcoin transactions worldwide" until it went bankrupt. Celsius Network was managing $12b. BlockFi was valued at $3b.

Again, it's a bit tough to say what the appropriate reference class is and to get a really good accounting. But reading through some lists of comparably sized companies, I would match these 4 failures against a population of maybe ~40 companies.

For a fixed valuation, potential is inversely correlated with probability of success: At very rough first approximation:

Byrne Hobart points out that gold is worth $9t, so if you think bitcoin has a 1% chance of becoming the new gold, $90b is a good place to start. We have to adjust down to discount that this value is in the future, and adjust down further for the associated risk, but this is the right ballpark.

We can also flip this equation to think about what a company's potential and current value imply about it's odds:

So if you see that Bitcoin could be worth $9t but is currenlty only worth $90b, the implied odds of success are 1% (again before accounting for risk and time).

Similarly, there have been some claims that SBF might become the world's first trillionaire. For this to happen, FTX would need to be worth around $2T, and is currently at $32b. This puts the implied odds of success at 1.6%.

We shouldn't take this math too literally, but we should take the prospects for FTX's growth really seriously. This is a platform that aims to displace a large chunk of all global financial infrastructure. $2t is not a bad estimate of potential value.

There is some more nuance we might want to apply here. If FTX realizes its full value in 10 years, at a 10% discount rate, today's valuation is discounted by 2.6x, and the implied odds should be adjusted upwards. Volatility also means the company is undervalued relative to a strict expected value, and that the odds should be adjusted upwards accordingly. There are various more sophisticated adjustments you could apply.

But the basic point stands: If a company has tremendous potential, and is only valued at a small fraction of that potential, the implied odds are not good.

Why does risk matter?

It is often worth speaking solely about expected value, and not worrying too much about risk. If a $5k intervention has a 50% chance of saving a life and a 50% chance of doing nothing, I am pretty comfortable calling this "an intervention which saves a life for $10k in expectation". In other cases, risk is more important.

Non-profit operational needs: If you are an EA non-profit funded by donors, you care very much that the grants come to you in a predictable way. If you get $10m one year with the expectation of another $10m the subsequent year and instead get $0, you will have to lay off a lot of staff. If in the third year you get another $10m, it will be tough to re-hire and restart operations. You are not at all indifferent to the risk your donors take on.

Opportunities do get worse: SBF has famously said that his utility function with respect to money is roughly linear. I made a similar argument back in 2020:

But for a rationalist utilitarian, returns from wealth are perfectly linear! Every dollar you earn is another dollar you can give to prevent Malaria. So when it comes to earning, rationalists ought to be risk-neutral

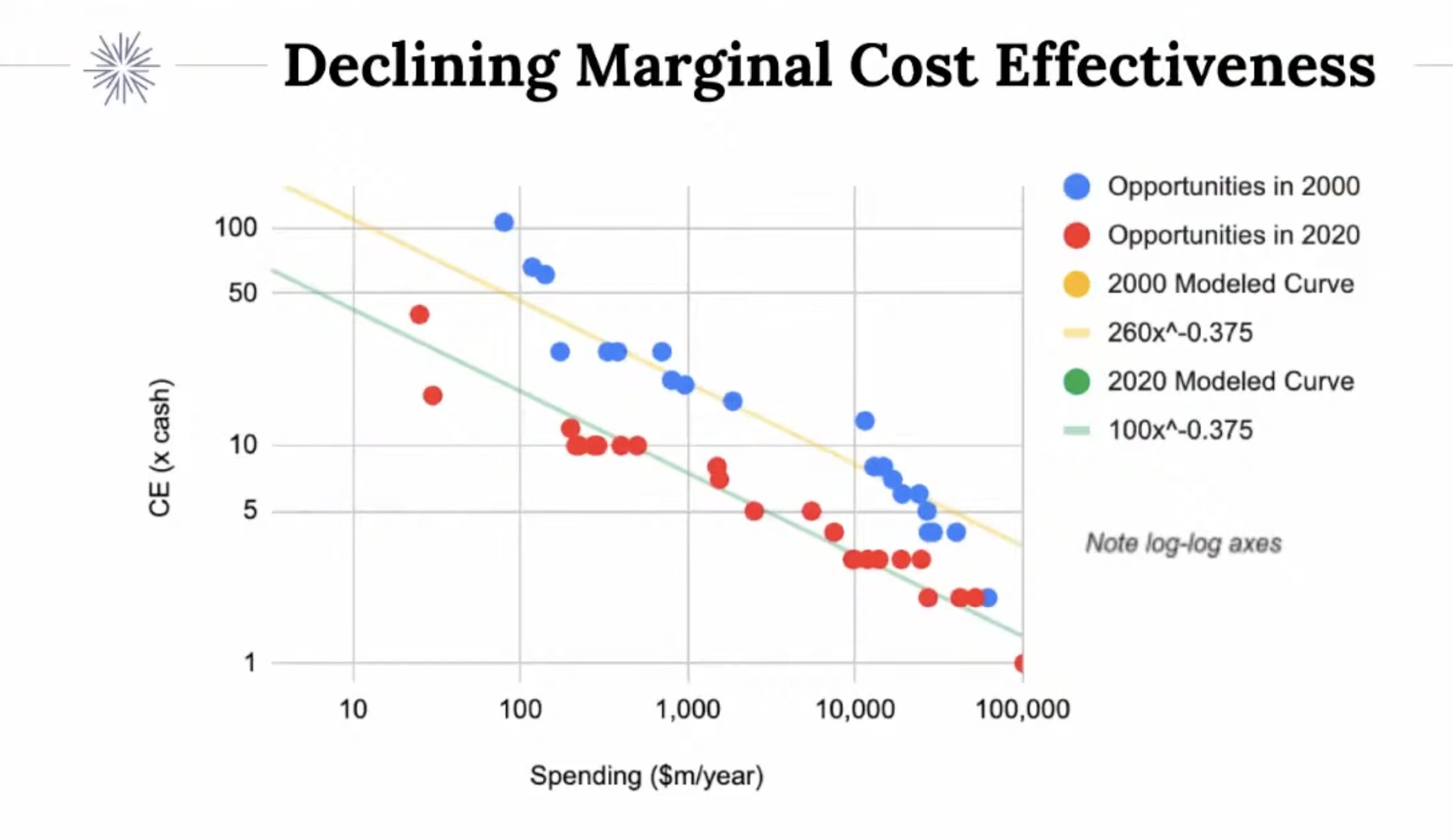

Though of course, it's not exactly linear, and at really extreme levels of wealth, this starts to matter. OpenPhil produced this chart which they urge us not to take literally, but does illustrate the declining value of money, even to a utilitarian. Eventually you run out of people who need bednets, or you are trying to distribute them to harder to reach places. There is some limit on how much money you can put into the most effective causes.

Again, not a literal interpretation, but just to get a sense of scale: Cost effectively drops by ~half as spending goes up ~10x.

I expect this effect to be more pronounced on the kinds of longtermist x-risk causes that FTX was particularly interested in funding. Even at current levels of wealth, when I talk to people about say, AI Safety, it does not feel clear that there are a bunch of non-profits that it would make sense to pump a bunch more money into.

Reputational risk: EA became a much more prominent movement in 2022. It is mainstream in a way that it wasn't previously, and remaining respectable and even popular will impact how much people want to work for EA orgs and give to EA causes. In this sense too, we should not be risk-neutral when it comes to dramatic outcomes.

Looking back from today

There are much better retrospectives than this one, but my aim is not to say what I want to with the benefit of hindsight. It is to say what I believe any reasonable person could have said even without that benefit. These views don't require any of the knowledge we have today or any deep insight into the operations of FTX. They are just the kind of basic outside-view takes that EA prides itself on.

We should not beat ourselves up for not knowing about the fraud or extent of the lies, but we absolutely should beat ourselves up for (from what I've seen from writing prior to 11/22), not making some version of these claims.

Since the FTX collapse, I periodically talk to people who say that they have "left EA". I ask what they're doing instead, and the answer is never some other version of altruism divorced from the EA movement, it is always just something that is not altruism.

I feel very bad when I have these conversations. There are still people who need bed nets. Still animals suffering in cages. Still a future that is fragile and precious. None of these facts about the world change as a result of what happened to FTX. This is easy for me to say because I have never thought about EA as a social circle. I don't go to EAG, I don't go to Bay Area house parties, none of my friends in real life are EAs.

"I found out that a priest was bad, and so now I no longer believe in God". I understand why someone might feel this way, but it just feels, to me, like that was never what any of this was about. I see faith as a matter between you and God, which is sometimes mediated in useful ways by a priesthood and community of practice, but does not need to be. We are all literate here. We are not denied access the way some people were in the past. If you care about doing good, facts about the community are incidental.

Of course, if a core tenet of your faith was something like "anyone who beliefs in God cannot do anything wrong", then I see how this would cause of questioning. But I don't see what's happened with FTX as incompatible in this way, because I have never seen EA as this kind of ideology.

In this sense, my own experience over the last couple of years has been to take the central questions of EA more personally and more seriously. Crises can, and often do, deepen rather than threaten faith.

In a practical sense, the losses the EA movement has experienced (in credibility, in funds, in human capital), make my marginal contributions more valuable. It feels more important than it did 2 years ago to do what I can. On an emotional level, I feel a greater sense that there is no secret cabal of powerful people ensuring that things go well, and subsequently feel more personal responsibility.

I am thinking hard about what is right, I am taking the gains I can see, and I am working hard to do the best that I can. I can only hope and suggest that others continue to do the same.

Also, the base rate of people following through on their publicly-professed charitable pledges is not 1. I'm not sure what base rate I'd use, but IIRC there is considerable dropout among those who take the 10 Percent Pledge.

There's this chart from the What trends do we see in GWWC Pledgers’ giving? subsection of GWWC's 2020-22 cost-eff self-evaluation:

Joel's comment on this is worth reading too.

Thanks. The self-evaluation explains that:

So I believe that chart is showing the combined effect of (a) imperfect retention; and (b) increased average donations by retained donors (probably because "the average GWWC Pledger is fairly young, and people’s incomes tend to increase as they get older"). With a sufficiently large number of pledgers, considering the combined effect makes sense because they will likely cancel each other out to some extent. When considering a single megadonor, I think one has to consider the retention issue separately because any increased-wealth effect is useless if there is 0% retention of that donor.

Also, to the extent that people were using the value of SBF's holdings in FTX & Alameda (rather than a rolling average of his past donations) in the analysis, they were already baking in the expectation that he would have more money in years to come than he had to donate now.

Makes sense. Their analysis treats large donors differently, although they don't mention anything about retention differences vs other pledgers. Given that GWWC say they "often already have individual relationships with them", my guess is it's probably slightly higher.

Does anyone care that FTX failed? They care that it stole. A complete fraud like Theranos only destroyed a billion dollars of investor money. Whereas a bank like FTX has access not only to investor money, but also to much more money in the form of deposits from people who don't think they're making an investment in a risky start up.

Yes, the collapse of FTX would have had significant effects on EA even if its cause was benign. People made life decisions based on beliefs about likely future funding, and charities made important decisions as well. Some of those decisions appear in retrospect to have not adequately accounted for the all-cause risk of FTX's collapse.

The title tells us the post is about what its author wishes they had said:

<<We should not beat ourselves up for not knowing about the fraud or extent of the lies, but we absolutely should beat ourselves up for (from what I've seen from writing prior to 11/22), not making some version of these claims.>>

It's not that benign-cause collapse is as harmful as fraud, but that at least a meaningful risk of any-cause collapse (or at least dramatic underperformance) should have been clear for any-cause failure.

The post mixes together several topics. If you want to write a better post, "What I wish Applied Divinity Studies had written," you should do so. But my comment is a response to the actual post, which may well be an intentional conflation.

I'm a bit confused about how the first part of this post connects to the final major section... I recall people saying many of the things you say you wish you had said... do you think people were unaware FTX, a recent startup in a tumultuous new industry, might fail? Or weren't thinking about it enough?

I agree strongly with your last paragraph, but I think most people I know who bounced from EA were probably just more of gold diggers, fad-follwing, or sensitive to public opinion and less willing to do what's hard when circumstances become less comfortable (but of course they won't come out and say it and plausibly don't admit it to themselves). Of the rest, it seems like they were bothered by a combination of the fraud, how EAs responded to the collapse, and updated towards the dangers of more utilitarian-style reasoning and the people it attracts.

I'm going off memory and could be wrong, but in my recollection the thought here was not very thorough. I recall some throwaway lines like "of course this isn't liquid yet", but very little analysis. In hindsight, it feels like if you think you have between $0 and $1t committed, you should put a good amount of thought into figuring out the distribution.

One instance of this mattering a lot is the bar for spending in the current year. If you have $1t the bar is much lower and you should fund way more things right now. So information about the movement's future finances turns out to have a good deal of moral value.

I might have missed this though and would be interested in reading posts from before 11/22 that you can dig up.

yeah, on second thought I think you're right that at least the arg "For a fixed valuation, potential is inversely correlated with probability of success" probably got a lot less attention than it should have, at least in the relevant conversations I remember

Thanks for writing this! I do feel like base rates/priors are something where many of us (including me) could have done better pre-ftx crash, and I am optimistic that we have learned from this and will do better the next time.

100.

The more sophisticated rationalizations for abandoning EA after the shame usually blamed some flaw in EA thinking ("causal decision theory!") or morality ("naive utiliatrianism!") or the community ("polyamory! dating coworkers!") for what SBF did. But, to follow the style of your post, the base rate of financial crimes by executives is not 0.

I want to see more retrospectives on the FTX incident so I really appreciate you taking the time to write this.

I like all your categories of things that we wish we had said more. Also, I basically disagree that:

To use your metaphor, lets imagine that 90% of all priests are moral and do what it says on the tin, and 10% of all priests are evil and they pretend to be moral priests while also preying on children. Do you think that when the moral priests find out that 10% of their brethren are evil, they should not worry about it? I think that if they are members of a larger church that includes some of these evil priests, then they should help figure out what changes to their church would help reduce the number of evil priests in the church as a high priority.

Likewise, I believe it is a high priority for EA to figure out how we can be confident that the next billionaire we create isn't SBF part deux. Does anyone claim that FTX wouldn't happen in today's EA?

If so, I'd love to interview you on the podcast series I just started with @Elizabeth. (I personally believe we are not ready for another FTX, but perhaps in a year we could be.)

Oh, I think you would be super worried about it! But not "beat ourselves up" in the sense of feeling like "I really should have known". In contrast to the part I think we really should have known, which was that the odds of success were not 100% and that trying to figure out a reasonable estimate for the odds of success and the implications of failure would have been a valuable exercise that did not require a ton of foresight.

Bit of a nit, but "we created" is stronger phrasing than I would use. But maybe I would agree with something like "how can we be confident that the next billionaire we embrace isn't committing fraud". Certainly I expect there will be more vigilance the next time around and a lot of skepticism.

In Catholicism, priests are considered sacred chosen instruments by and for god, to mediate between him and lay people. If a given priest is bad, that throws into question whether god has poor judgement, but god is almighty so he doesn’t make mistakes. (Even more so if the pope is implicated, as his word is the direct word of god). Therefore probably he doesn’t exist.

Only later denominations conceptualise faith as primarily a direct relationship between you and god, in part as a response to this dilemma. But if you’re Roman Catholic, your whole religion is thrown into question by widespread priest criminality, and it seems reasonable to have a more modern response than Martin Luther starting a whole new religion, and just conclude that god actually doesn’t exist.

Yeah this is all right, but I see EA as being since it's founding, much closer to Protestant ideals than Catholic ones, at least on this particular axis.

If you had told me in 2018 that EA was about "supporting what Dustin Moskovitz chooses to do because he is the best person who does the most good", or "supporting what Nick Bostrom says is right because he has given it the most thought", I would have said "okay, I can see how in this world, SBF's failings would be really disturbing to the central worldview".

But instead it feels like this kind of attitude has never been central to EA, and that in fact EA embraces something like the direct opposite of this attitude (reasoning from first principles, examining the empirical evidence, making decisions transparently). In this way, I see EA as already having been post-reformation (so to speak).

Later denominations which conceptualize faith as primarily a direct relationship between an individual and God came because humanity began to rediscover the truth in the bible. During the Dark Ages (a period lasting between 500 to 1,000 years), Roman Catholicism did not permit lay people from possessing or reading a bible, so much of the truth of the Gospel was lost during that time.

A reasonable response (regardless of its modernity) to the question of God's existence should first and foremost consider what God has to say, and the only record of that is in the bible.