Let’s look at how we use frameworks to prioritize causes. We’ll start by looking at the commonly-used importance/neglectedness tractability framework and see why it often works well and why it doesn’t match reality. Then we’ll consider an alternative approach.

Importance/neglectedness/tractability framework

When people do high-level cause prioritization, they often use an importance/neglectedness/tractability framework where they assess causes along three dimensions:

- Importance: How big is the problem?

- Neglectedness: How much work is being done on the problem already?

- Tractability: Can we make progress on the problem?

This framework acts as a useful guide to cause prioritization. Let’s look at some of its benefits and problems.

Why it doesn’t match reality

When we consider investing time or resources into a cause, we want to know how much good our investment will do. In the end, this is all we care about1: we want to know the true marginal impact of our efforts.

Importance/neglectedness/tractability (INT) acts as a proxy for true marginal impact. We don’t actually care about these factors on their own; we only care about how they affect marginal impact, and we make the assumption that they usually do. But that doesn’t mean it’s reasonable to do something like score causes on each of importance/neglectedness/tractability and then add up the scores to rank causes2.

Why it works well for comparing causes

Each of the three dimensions of INT tells us something about how much good we can do in a cause:

- In a more important cause, we probably have more room to do good.

- Causes typically experience diminishing marginal utility of investments, so a more neglected cause should see greater marginal utility.

- In a more tractable cause, we can make greater progress with our efforts.

Each of these tells us something that the other two do not.

Sometimes we can measure a cause’s importance/neglectedness/tractability a lot more easily than we can assess our marginal impact, so it makes sense to use these as a proxy. When we’re looking at causes, we can’t always even meaningfully say how much marginal impact we can have in a cause, because we could do lots of different things that qualify as part of that cause. With INT, we can get a sense of whether we expect to find strong interventions within a cause.

Do people apply it correctly?

INT has its uses, but I believe many people over-apply it.

Generally speaking (with some exceptions), people don’t choose between causes, they choose between interventions. That is, they don’t prioritize broad focus areas like global poverty or immigration reform. Instead, they choose to support specific interventions such as distributing deworming treatments or lobbying to pass an immigration bill. The INT framework doesn’t apply to interventions as well as it does to causes. In short, cause areas correspond to problems, and interventions correspond to solutions; INT assesses problems, not solutions.

In most cases, we can try to directly assess the true marginal impact of investing in an intervention. These assessments will never be perfectly accurate, but they generally seem to tell us more than INT does. INT should mostly be used to get a rough overview of a cause before seriously investigating the interventions within it; but we should remember that INT doesn’t actually describe what we fundamentally care about. Once we know enough to directly assess true marginal impact, we should do that instead of using the importance/neglectedness/tractability framework.

Perhaps this isn’t always the best way to compare causes at a high level. Instead of comparing causes on importance/neglectedness/tractability, we could look at promising interventions within each cause and compare those. In the end, we fund interventions, not causes, so we may prefer to do things this way. When I decided where to donate last year, I looked at strong interventions within each cause and compared those against each other rather than comparing causes at a high level.

Framework for comparing interventions

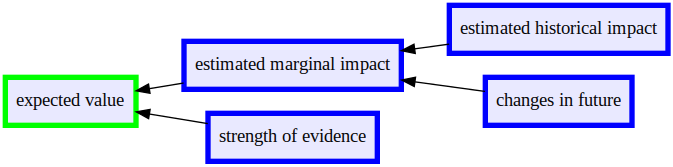

The INT framework works well for comparing causes at a high level, but not so well for individual interventions within causes. How can we estimate an intervention’s impact more directly? To develop a better framework, let’s start with the final result we want and work backward to see how to get it.

Ultimately, we want to know an intervention’s marginal impact, or expected value: how much good will our extra investment of time or money do for the world?

Unfortunately, we can’t know the expected value of our actions without seeing the future. Instead, we must make our best guess. To guess the true marginal impact of an intervention, we want to make an estimate and then adjust based on its robustness. To do this, we need to know the estimated marginal impact and the strength of evidence behind our estimate.

When we’re trying to estimate marginal effects we usually want to know estimated historical impact, even though future effects may look different. For example, to evaluate GiveDirectly we can look at historical evidence of cash transfers; or when assessing REG we can look at its money moved during prior years. Then we can look for reasons to expect future impact to look different from historical impact.

Click on the image to see the full-size version.

Possible Extensions

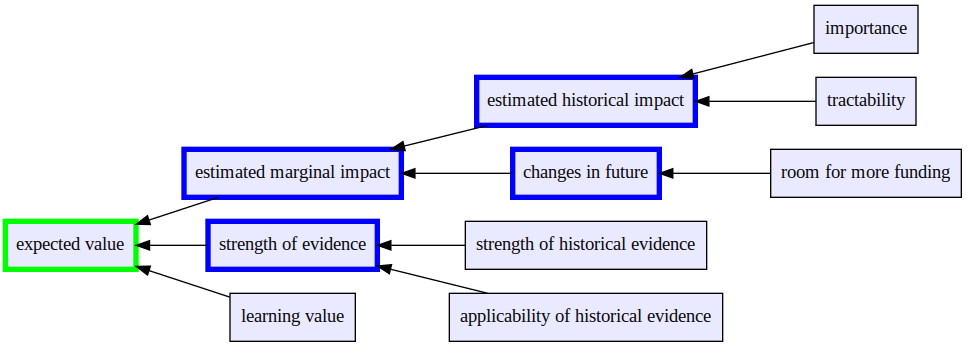

Let’s consider a few ways of adding detail to this framework.

We may want to break down strength of evidence even further. Determining strength of evidence will probably require looking at the strength of our historical evidence and considering how well it applies to future scenarios.

If we want, we can re-incorporate a version of importance/tractability/neglectedness. When estimating the historical impact of an intervention, we care about its importance and tractability. When we try to figure out how its impact will change in the future, we look at its room for more funding, which is related to neglectedness.

We may particularly care about learning value in a way that this framework doesn’t capture. Perhaps we expect an intervention to tell us something useful in the long term, but we don’t know what, so we have a hard time pinning down the impact of this learning. We could instead represent this by factoring in learning value to our final estimate. I tend to believe we should try to estimate the expected value of learning rather than using it as a separate input, but I can see a good case for doing things this way.

If we include all these extensions, we get a new, impractically complicated evaluation framework:

Click on the image to see the full-size version.

Example Application: Raising for Effective Giving

Last year I donated to Raising for Effective Giving (REG) and used a looser version of this framework to estimate its impact:

- I estimated REG’s historical impact.

- I considered the strength of evidence for its historical impact, and the evidence for its future impact.

- I looked at how much impact new funding might have compared to past funding.

At the time I looked at a lot of other things, but it turned out that these three factors mattered most.

Notes

-

Some people are not consequentialists and they care about other things, but that’s incorrect and a major diversion so I’m not going to go into it. ↩

-

80,000 Hours does say to take its rankings with a lot of salt (“think [tempeh] sandwich with [avocado], where instead of bread, you have another layer of salt”). At a certain point you have so much salt that there’s no point in creating the ranking in the first place. ↩

I disagree about the cause area and organization being more important than the intervention. To me, it's all about the intervention in the end. Supporting people that you "believe in" in a cause that you think is important is basically a bet that you are making that a high impact intervention will spring forth. That is one valid way of going about maximizing impact, however, working the other way – starting with the intervention and then supporting those best suited to implement it, is also valid.

The same is true for your point about a funder specializing in one knowledge area so they are in the best position to judge high impact activity within that area. That is a sensible approach to discover high impact interventions, however, as with strategy of supporting people, the reverse method can also be valid. It makes no sense to reject a high potential intervention you happen to come across (assuming its value is fairly obvious) simply because it isn't in the area that you have been targeting. You're right, this is what Open Phil does. Nevertheless, rejecting a high potential intervention simply because it wasn't where you were looking for it is a bias and counter to effective altruism. And I object to your dismissal of interventions from surprising places as “random.” Again, this is completely counter to effective altruism, which is all about maximizing value wherever you find it.