In the conclusion to Moral Uncertainty, Krister Bykvist, Toby Ord, and William MacAskill write:

Every generation in the past has committed tremendous moral wrongs on the basis of false moral views. Moral atrocities such as slavery, the subjection of women, the persecution of non-heterosexuals, and the Holocaust were, of course, driven in part by the self-interest of those who were in power. But they were also enabled and strengthened by the common-sense moral views of society at the time about what groups were worthy of moral concern.

Given the importance of figuring out what morality requires of us, the amount of investment by society into this question is astonishingly small. The world currently has an annual purchasing-power-adjusted gross product of about $127 trillion. Of that amount, a vanishingly small fraction---probably less than 0.05%--goes to directly addressing the question: What ought we to do?

They continue:

Even just over the last few hundred years, Locke influenced the American Revolution and constitution, Mill influenced the [women's] suffrage movement, Marx helped birth socialism and communism, and Singer helped spark the animal rights movement.

This is a tempting view, but I don't think it captures the actual causes of moral progress. After all, there were many advocates for animal well being thousands of years ago, and yet factory farming has persisted until today. At the very least, it doesn't seem that discovering the correct moral view is sufficient for achieving moral progress in actuality.

As quoted in the Angulimālīya Sūtra, the Buddha is recorded saying:

There are no beings who have not been one's mother, who have not been one's sister through generations of wandering in beginningless and endless saṃsāra. Even one who is a dog has been one's father, for the world of living beings is like a dancer. Therefore, one's own flesh and the flesh of another are a single flesh, so Buddhas do not eat meat.

A few hundred years later, in the 3rd century BCE, The Edict of Emperor Ashoka reads:

Here (in my domain) no living beings are to be slaughtered or offered in sacrifice. Nor should festivals be held, for Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, sees much to object to in such festivals

Of course, the slaughter of living beings and consumption of meat would continue for thousands of years. In fact, as I argued previously, the treatment of animals has likely declined since Ashoka's time, and we now undertake factory farming of unprecedented scale and brutality.

I don't believe that this is due to our "false moral views". Unfortunately, we seem unlikely to give up factory farming until we develop cost-competitive lab grown meat, or flavor-competitive plant-based alternatives.

Similarly, the abolition of slavery was plausibly more economically than morally motivated. Per Wikipedia:

...the moral concerns of the abolitionists were not necessarily the dominant sentiments in the North. Many Northerners (including Lincoln) opposed slavery also because they feared that rich slave owners would buy up the best lands and block opportunity for free white farmers using family and hired labor. Free Soilers joined the Republican party in 1854, with their appeal to powerful demands in the North through a broader commitment to "free labor" principles. Fear of the "Slave Power" had a far greater appeal to Northern self-interest than did abolitionist arguments based on the plight of black slaves in the South.

Switching gears, here's a much more explicit case of moral philosophy failing to enable social change. From Peter Singer:

Jeremy Bentham, before the 1832 Reform Act was passed in Britain, argued for extending the vote to all men. And he wrote to his colleagues that he would have included women in that statement, except that it would be ridiculed, and, therefore, he would lose the chance of getting universal male suffrage. So he was aware of exactly this kind of argument. Bentham also wrote several essays arguing against the criminalization of sodomy, but he never published them in his lifetime, for the same reason.

Here we have a case where a moral philosopher explicitly acknowledges that he has discovered a more progressive moral view, but declines to even publish it. So the fact that Bentham made progress in moral philosophy did not allow him to make any actual moral progress. The two are totally decoupled.

What about gay rights? In the Bykvist et al. narrative, some moral philosopher comes around, determines that homosexuality is okay, and everyone celebrates. But what we've seen in the last few decades was not a slow dwindling of homophobia, but a massive resurgence of previously vanquished attitudes. The moral arc has not been monotonic.

So what really did happen? Here's one alternative narrative:

-

Despite efforts by LGBT activist groups, "little change in the laws or mores of society was seen until the mid-1960s, the time the sexual revolution began."

-

The sexual revolution was itself spurred largely by oral contraceptives, invented in the 50s, and first approved in the US in 1960.

So rather than being driven by moral philosophy, what we have instead is a societal shift driven by a scientific advance, which subsequently allowed rapid liberalization.

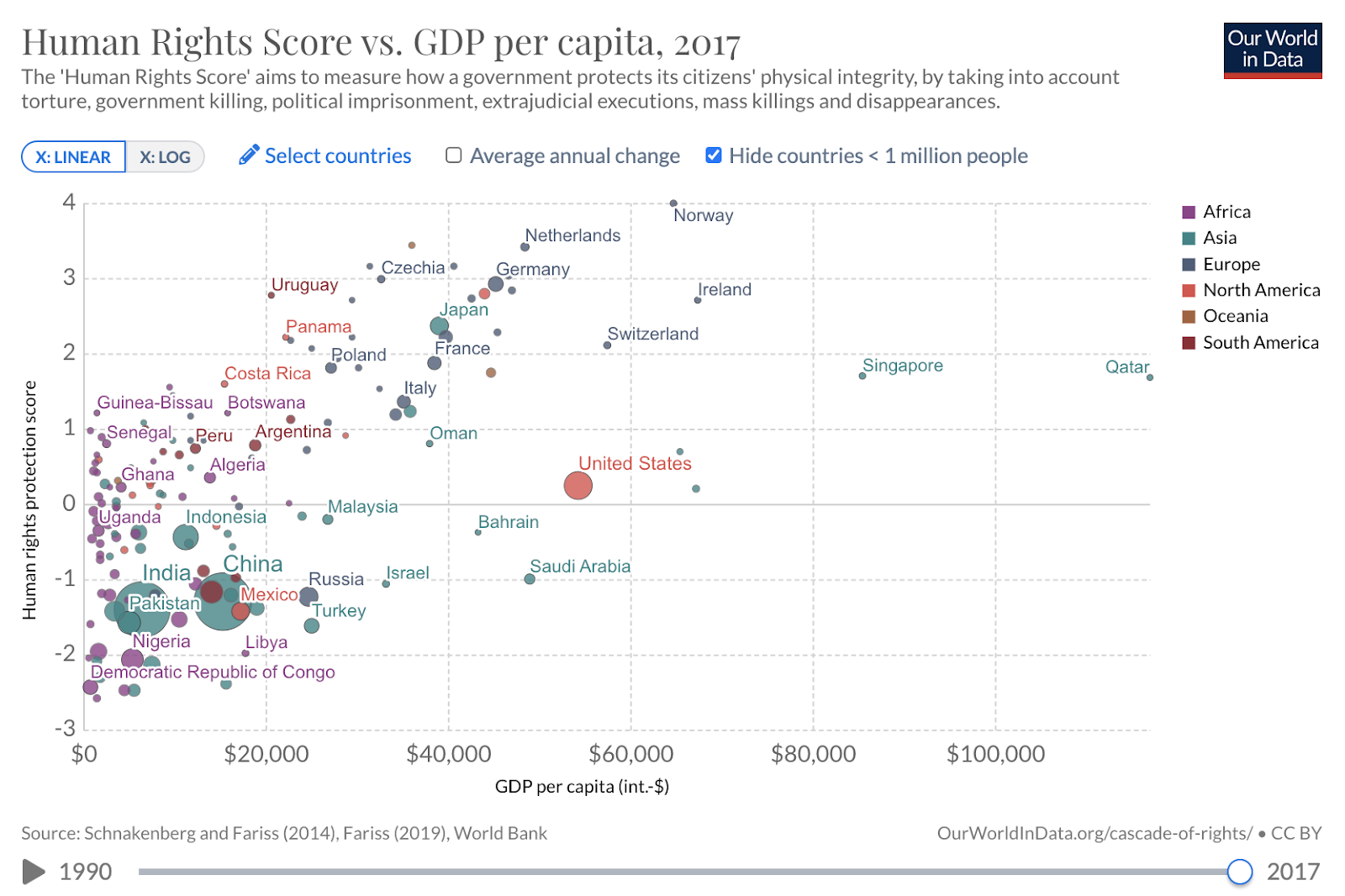

Can we investigate the claim on a more macro scale? There are some charts from Our World in Data comparing human rights to GDP per capita:

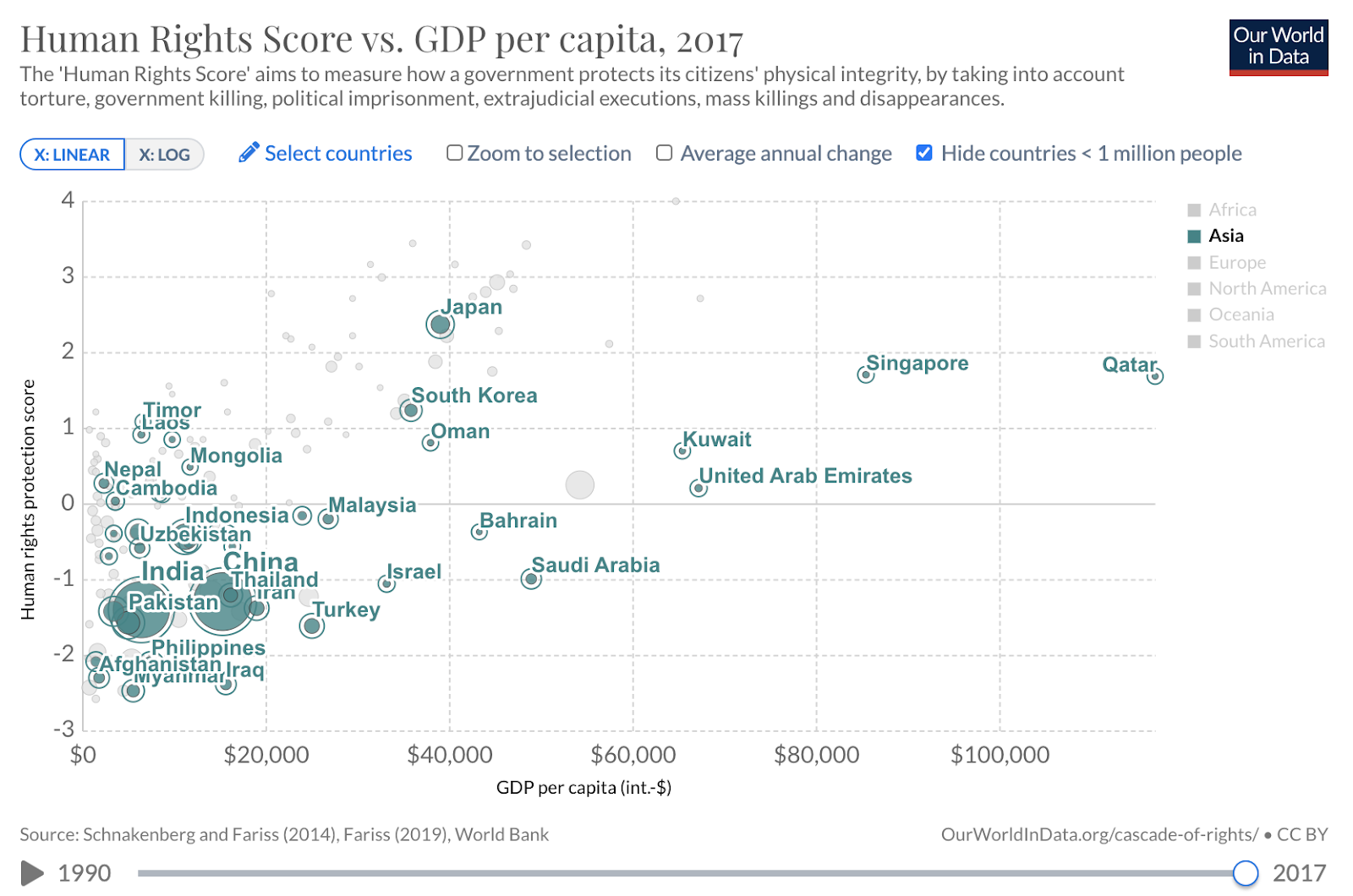

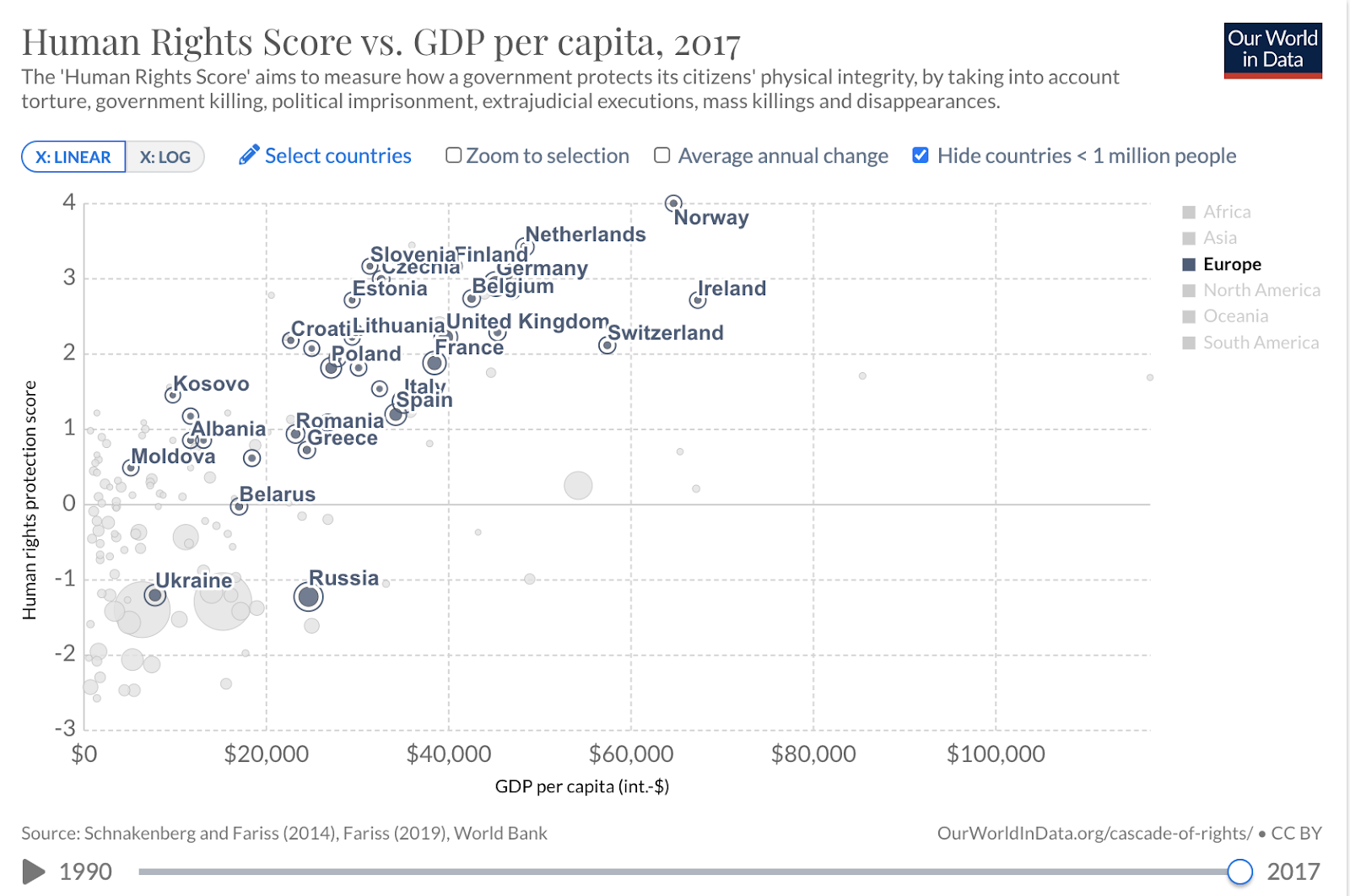

You could argue that this is really just tracking some underlying variable like "industrialization" or "western culture". But here are some more breakdowns by continent:

Admittedly, even assuming there is a causal relationship, I don't know which way it goes! There are numerous papers demonstrating the link between democracy and economic growth, so there is at least some reason to believe that economic progress is not primary.

Overall, I would guess that "progress" occurs as a confluence of various domains. Perhaps without a social need, or without a moral demand, oral contraceptives would never have been invented in the first place. But I remain skeptical that investing directly in moral philosophy will accelerate humanity's march out of moral atrocities.

There is, after all, currently concentration camps in China, a famine in Yemen, and a genocide in Myanmar. The bottleneck does not seem to be our "false moral views.

Finally, I'd like to posit that the perspective set forth by Bykvist et al. is all too compelling. Consider their statement again: "Every generation in the past has committed tremendous moral wrongs on the basis of false moral views."

It's a comfortable view, and one that allows us to put a kind of moral distance between ourselves and the horrors of the past. We get to say "yikes, that was bad, but luckily we've learned better now, and won't repeat those mistakes". This view allows us, in short, to tell ourselves that we are more civilized than our monstrous ancestors. That their mistakes do not reflect badly on ourselves.

As tempting as it is to wash away our past atrocities under the guise of ignorance, I'm worried humanity just regularly and knowingly does the wrong thing.

To some limited degree, some people have some beliefs that are responsive to the strength of philosophical or scientific arguments, and have some actions that are responsive to their beliefs. That's about as weak a claim as you can have without denying any intellectual coherence to things. So then the question becomes, is that limited channel of influence enough to drive major societal shifts?

Or actually, there might be two questions here: could an insight in moral philosophy alone drive a major societal shift, so that society drifts towards whichever argument is better? and, to what extent has actual moral progress been caused by intellectual catalysts like that?