Introduction

There is a general tendency for people entering the EA community to be initially more interested in high-impact global health interventions like those endorsed by GiveWell, and to be attracted to the movement through organizations like Giving What We Can and The Life You Can Save discussing issues primarily related to global poverty reduction. However, with time inside the movement, the EA Survey shows a trend to become more interested in work specifically aimed at reducing existential risk. I recognize that sometimes individuals move in the opposite direction, but the net flow of prioritization is revealed in the survey as originating in global poverty and drifting towards “long-term future/existential (or catastrophic) risk” as people become more deeply involved in the movement.

I credit this shift primarily to the compelling philosophical arguments for long-termism and the importance of the distant future in expected value calculations. I take issue with the inference however, that reducing global poverty is not a cause which can significantly benefit the long-term future. Perhaps that is fair given the predominant focus around short-term measurable gains in the RCT-driven style of global health work engaged in by early EA aligned orgs (cash transfers, bed nets, deworming, etc). But with a more long-termist approach to global poverty reduction, this apparent shortcoming could perhaps be remedied.

Another possibility that could explain the shift is that people who primarily value global poverty reduction are disheartened by the amount of focus within the movement on issues they perceive to be disconnected from their initial purposes and become disengaged with the movement; this is my concern. If this is occurring then this would select for EAs who embrace causes traditionally categorized as long-term future focused. If this is the case, it seems a great loss to the movement, and it seems important to recruiting and organization building to bring more meaningful discussions regarding poverty reduction to forums like this. Other ideas surrounding possible causes for this apparent discrepancy have been discussed here.

My general sense is that this creates an artificial and false dichotomy between these cause areas and that, in discussions which center around long term future vs. saving lives now, people may be over simplifying the issue by failing to acknowledge the wide range of activities that fall under “global development.” In other words, this work is often implicitly reduced to the short-termist work done by EA orgs like GiveWell’s top charities, rather than more holistic, growth oriented development efforts at a larger scale. Some intelligent people within the movement seem to prefer a justification of global development on its own merits using different kinds of philosophical reasoning and leave long-termism to those working in existential risk reduction. Some even seem to suggest that global development may be harmful to the long-term-future (some reasons why will be discussed below). But if certain types of global development were truly harmful to the long-term future, this should at least be an important area of research and advocacy for long-termists. Similarly, if strategic global development can be a useful tool for reducing existential risk then it makes sense to foster interdisciplinary collaboration on this important intersection of expertise.

Here I will present the following 3 arguments (in decreasing order of confidence):

1. Reducing global poverty is unlikely to harm the long-term future.

2. Addressing global poverty with a long-termist perspective can significantly benefit the long-term future.

3. Reducing global poverty with a long-termist perspective may reduce existential risk even better than other efforts intended specifically to reduce existential risk.

Reducing global poverty is unlikely to harm the long-term future

While this statement is widely accepted in the general public it has been questioned by many intelligent people within the EA movement. The primary reason I have seen cited is that with increasing human growth and development come greater existential threats. Here I address a few common speculative concerns and reasons why they seem not to be robust critiques to those familiar with the downstream effects of development efforts.

Problem 1- Economic growth may accelerate parallelizable work like AGI preferentially over highly serial work like friendly AI. Also, general technological advancement is likely to unintentionally introduce new types of threats. (2 related issues, grouped together because the response is essentially the same)

Response to Problem 1- First, it’s far from proven that economic growth (particularly in impoverished nations) would increase the risk posed by AI. A great deal has been written on the effects of economic growth in general on existential risk. One paper concludes “We may be economically advanced enough to be able to destroy ourselves, but not economically advanced enough that we care about this existential risk and spend on safety.” The paper itself examined different models of growth vs. risk and in general promotes faster economic growth as a means of decreasing risk over the long term. I would go one step further in suggesting that the optimal way to achieve the goal of advancing the objectives of increased caring and stalling the indiscriminate technological growth that threatens humanity is to divert resources from more technologically advanced countries to aid in the development of technology poor nations (or perhaps better yet, end economic policy which perpetuates wealth extraction).

If there is a negative effect for this particular risk (AI), it would most likely be from economic development in advanced nations that are on the cutting (or potentially world ending) edge of developing these new technologies. The redistribution of resources from a country with relative abundance to one of relative poverty would be more likely to have an overall slowing effect on the capacity of wealthy nations to advance such technologies because they will have less surplus resources within their economy to do so. While there is expected to be a global net increase in economic capacity from improved utilization of human resources locked in poverty, the marginal effects of this redistribution of resources would be to increase economic and technological capacity in the developing nations where the advancement of groundbreaking technology is relatively less likely to occur in the short term. This would, in theory, allow for more time in developed nations to implement strategies for implementing differential technology development. For more reading on this key concept of differential development, Michael Aird has compiled a few relevant resources here. (also quick shout out to him for giving quality feedback on this paper!)

I think it is also important to recognize that some strategies for poverty reduction may be considered “win-win” and harder to recognize the benefits in terms of creating space for differential development. My understanding is that most of the true win-win scenarios have their roots in increased global connectivity and international collaboration, which also seems like a win for existential risk reduction. I think we should carefully consider these scenarios in more detail and suspect that different strategies would be found to have different effects on the security of the long-term future.

Problem 2- Addressing global poverty could exacerbate global climate change as reducing premature mortality leads to population growth and more people reach a standard of living where consumption of fossil fuels is increased.

Response to Problem 2- In the short term this is most likely true. The catch however is that historically, the most reliable methods for stabilizing population growth have involved promoting economic growth. The wealthier a country becomes; the smaller family size becomes. This relationship between development and population growth actually argues in favor of economic growth as a means of controlling climate change in the long term.

That is not to say that effects of climate change should be ignored. Addressing climate change is also of great importance to the work of reducing poverty as highlighted in high level discussions on this topic. These topics run together in ways that are nearly inseparable given their relationship and efforts to address one effectively should include the other as exemplified in plans like the “Global Green New Deal” and the work of the UN Development Programme. These are some real life examples of how development work, with a long-termist perspective, can contribute to reducing existential risk in important ways. It seems clear that a world with less extreme poverty and economic inequality would be better optimized not only to stabilize population growth and withstand the risks that come with climate change but also for global coordination and peace which are essential for addressing other x-risks (these are discussed in more detail below).

Problem 3: According to the BIP framework it can be harmful to the long term future to increase the intelligence of actors who are insufficiently benevolent or to empower people who are insufficiently benevolent and/or intelligent. Efforts to indiscriminately empower the world’s poor may be unintentionally leading to future harm based on these principles (this is a hypothetical point and not something I have seen argued for by those who created the framework or other EA’s).

Response to Problem 3: For this view to reflect real harm it requires the assumption that people generally do not possess sufficient benevolence and intelligence in the ways specified by the framework. However, it is also important to note that improving people’s welfare may be an important way to increase the propensity of people to value benevolence and to become more educated. At the very least, the strong association which is seen between economic growth and education is somewhat bidirectional. The evidence between benevolence and economic opportunity is much weaker but this may be due to a comparative lack of research in this area. But supposing a person holds a sufficiently pessimistic view on the potential of others to have a net positive impact on the safety of the long term future, there should still be an understanding that selectively empowering good and intelligent people can have an outsized impact on reducing existential risk. If EA involvement in global development can create a major shift in development efforts which relies on this framework rather than indiscriminate efforts then at a minimum the result would be causing less harm (overall net benefit). This idea is also discussed more below.

Addressing global poverty thoughtfully can significantly benefit the long-term future

From “saving lives” to holistic improvements to life more generally

The focus on “saving lives” and impact-focused, evidence-based charity has been a persuasive gateway for many people (including myself) to enter a larger realm of EA thought. As such, it is a powerful tool for movement building. However, I believe that as long-termist philosophy gains traction, this should naturally lead people to consider a broader range of development models and compare their expected long-term benefits. That assessment of benefit would include an attempt to estimate their impacts on existential risk which is something EA orgs may be uniquely positioned to do. Ultimately, once people inclined to work on global poverty begin to embrace the long-termist ideals of the EA movement, the goal of “saving lives” should probably shift toward the goal of unlocking human potential strategically in ways that carefully consider the downstream impact of those actors in securing the long-term future.

The ultimate flow through effects of any given action are likely the principal drivers of total impact but they are extremely hard to evaluate accurately. There are several approaches to dealing with flow through effects and I believe the only method that is clearly wrong is to ignore them. We can sometimes at least identify clear general trends and recognize patterns in downstream effects which help inform right actions. The idea that “saving lives” through specific, disease oriented approaches alone may not optimize for downstream effects is a legitimate critique of “randomista development” work done by popular EA organizations like GiveWell. This is however just one piece (albeit the most visible) of the global development cause area. An excellent discussion on shifting away from “randomista development” in favor of approaches that target less measurable but likely much more effective development interventions focused on holistic growth can be found here. Also, groups like Open Philanthropy are using a more “hits based” approach as discussed here. Another great forum piece on long-termist global development work can be found here. I recommend that people already engaged in addressing global poverty within EA consider a more long-termist approach which attempts to engage with root causes of poverty rather than just the short-medium term impact.

Unlocking Human Potential

GiveWell co-founder Holden Karnofsky summarized the basic principle of unlocking human potential in an interview where this topic was touched on when he said, “You can make humanity smarter by making it wealthier and happier.” I think it is important to conceive of the opposite of poverty not just as having material goods but as being relatively self-sufficient and capable of using time, talent and resources to help others and better society. It is this privileged position which allows most people reading this to be able to contemplate issues like the long-term future. If we recognize the role of this relative lack of poverty in our own journey as being an important part of arriving at an altruistic mindset, it is reasonable to suppose that others, if provided with similar circumstances might be more willing and able to engage in this type of important work as well. For more of Holden’s thoughts check out the rest of the interview linked above or this discussion on flow through effects.

Clearly, reaching a certain material standard of living alone does not guarantee that people will engage in more altruistic behaviors. One useful framework for approaching this could be the BIP framework (benevolence, Intelligence, power). This seems like a tool which could greatly inform the individual donor in comparing the marginal benefit of different interventions on the long term-future. The basic idea is:

“… that it’s likely good to:

- Increase actors’ benevolence.

- Increase the intelligence of actors who are sufficiently benevolent

- Increase the power of actors who are sufficiently benevolent and intelligent”

Applied to the global development context this has significant implications. I suspect that there are a significant number of good and intelligent people living in poverty who could have an outsized impact on the future. This may be particularly true if by selectively targeting benevolent actors for educational opportunities and following up the intellectual advancements of those individuals with empowering opportunities for employment in high-yield fields, it can inspire others to follow in their footsteps as well as empower the right individuals to contribute to their communities in meaningful ways. This seems true in countries across the income distribution but these efforts may be particularly cost effective in the world’s least developed nations. These applications may be of interest to long-termist folks working in global development as we seek to promote the growth of leaders in the developing world that will be best aligned with the kind of sustainable growth which will best secure the long term-future.

This type of framework may give renewed power to causes like improving education and teaching good values which are typically ignored in development models focused on short term, measurable impact. Contrary to the expressions in the last link, there may be some evidence based ways to improve educational quality in cost-effective ways. I suggest that a sort of differential development that prioritizes growing human capacity to do good could be an important area for future research within the EA movement. While this framework may be difficult to employ at a policy level, it is reasonable to suppose that even modest shifts, in the general direction of long-termist strategy for development might have large impacts on the long-term future.

Global Catastrophic Risks (GCRs) and Poverty

In discussing GCRs it is important to note that not all scenarios lead invariably to extinction or otherwise critical outcomes for the long-term future of humanity. One of the important factors that can make a difference is that people living in poverty are disproportionately more at risk from GCRs and a threshold of people with resources sufficient to survive a global catastrophe may be what keeps it from becoming a true crisis for the future of humanity. This is the case for nearly every type of non-extinction level catastrophe (with the possible exception of a pandemic); that those with power and resources are much more likely to survive such an event. To me, this clearly suggests that decreasing poverty and increasing human welfare can promote resilience against such future risks. A more robust world through poverty reduction may well be the difference between a “crunch, shriek or whimper” scenario and effective recovery from a difficult situation.

Investing Wisely in Humanity’s Future

One way to view this approach is as an investment in human potential. In the discussions regarding giving now vs. giving later it is often viewed as wise to invest and give larger amounts at a later time to have greater impact. If you believe that the most undervalued resource on the planet is the potential of good and intelligent people limited by poverty (at least more undervalued than the companies in your stock portfolio), then it makes sense, to invest in the ability of those people to have impact on others which continues rippling outward and accruing a sort of compounding interest. If you have already come to the conclusion that giving now is the preferable option then you may wish to prioritize this form of giving in ways that optimize for the flow-through effects that have the highest expected value for the long-term future.

For those who favor the role of the patient philanthropist, there is still a clear role for long-termist considerations of global development. In that case, the discussion of which specific interventions best optimise the long-term future are postponed till later supposing that improved knowledge and wealth will be more beneficial at a future date. One paper gave an interesting critique of the idea of compounding interest of flow-through effects and favors the patient approach (5.1.2 for the case for giving now, 5.1.3 for the critique).

Ultimately, the benefit to the long-term future from employing this philosophy to global development seems robust across several different moral decision-making theories. The case for differing development strategies considering their most likely impact on things like existential risk seems like it should be an important consideration. Groups like Open Philanthropy have done some work looking at global catastrophic events but this might be something which could be more fully integrated with thinking about global development in its relation to these risks. Particularly, it seems like it would be helpful to guide individual donors in making their contributions in ways that better optimize for long-term benefit like how GiveWell does with short term, measurable results. As an individual donor with limited time and information these determinations can seem even more daunting but remain essential to the long-termists inclined to donate towards poverty reduction interventions.

Shifting Global Priorities

Currently the UN’s sustainable development goals do not include x-risks other than climate change. The number one priority is eliminating global poverty because this is a unifying moral imperative with broad support across cultures and nation states. While coordinated global efforts on this front may not be ideal, it is the system which we have to address issues of global priority which require international collaboration/coordination.

Barring a dramatic global shift in values, I suspect that appetite for international collaboration prioritizing other x-risks at that level will not be possible while extreme forms of poverty exist at any significant magnitude. A person who believes that x-risk should be a global priority and that a certain threshold of international coordination on these issues may be essential for the survival of humanity may find it at least plausible that addressing existing global priorities may be prerequisite to gaining relative popular interest for prioritizing existential threats to humanity.

As suggested by Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, issues concerning physiologic needs like food, shelter and water will naturally be prioritized by individuals and governments over threats to safety. The neglectedness of x-risk may not be justified, but it is certainly understandable why the persistence of these basic problems overshadows those more abstract concerns and resolving some of these issues may be an effective way to shift global priorities

Benefits of reducing global poverty thoughtfully may reduce existential risk EVEN BETTER THAN other efforts intended specifically for that purpose.

Disclaimer: This is almost certainly destined to be the most controversial argument, so I’ll just preface this by admitting that this is an idea that I am not particularly confident in but do feel that I have some thoughts on this which may add to more thoughtful discussion. I am also at significant risk for bias on this topic. I am a physician with specialized training in public health and tropical medicine and much more familiar with issues relating to global poverty than with issues surrounding existential risk which clearly colors my perspective (this could all be some form of post hoc rationalization of my career choice and preconceived values). Given this bias, this convenient convergence may not be as strong as my intuition tells me.

Reducing existential risk seems to be a worthy endeavor and the following comparison assumes that arguments in favor of long-termism are robust. To compare global development work with more standard x-risk reduction strategies, I will use the popular EA framework of assessing relative Importance, Tractability and Neglectedness (ITN) but will do so in reverse order to facilitate a more logical progression of ideas.

Neglectedness

While traditionally, global development has been viewed as less neglected than other specific mechanisms for existential risk reduction, it may be useful to think instead of the neglectedness of the work of using global development for existential risk reduction. This represents a relatively small piece of the current development efforts and may be something EA is uniquely positioned to address with experts in both x-risk and development with overlapping values.

Meanwhile, interest in things like AI safety, climate change, and bioterrorism seems to have been increasing in recent years. These are still apparently neglected things in the grand scheme of things but their relative neglectedness seems many times less today than it may have been even just 5-10 years ago. As interest and research into other forms of existential risk increases, we have to remember that this lowers the marginal expected utility of addressing these issues through these increasingly popular, specific areas of focus.

Tractability

In this regard, most attempts to influence the long-term future (including global development) face large amounts of uncertainty. We have relatively little true, quantifiable knowledge about the probability of these kinds of events, their root causes and the associated solutions. Of all the threats to humanity, the greatest risks might still be black swan scenarios where we don’t even know enough about the things we don’t know to see them coming at the present time. Maybe the greatest risk to humanity will be manipulation of dark matter or of spacetime using some form of warp engines (currently these are wildly speculative concerns) or something of which we have yet to develop the ability to imagine. Appropriate estimation of tractability for these kinds of events is greatly limited by the paucity of knowledge of all the risks in expected value calculations. Beliefs about the importance of any particular x-risk is, by nature, on weak epistemic footing and should remain open to additional information as it becomes available.

An appropriate response to this type of uncertainty might then be an effort to increase the resilience of all of these efforts by focusing more on the generalizable capacity of humanity to address issues in the most collaborative and insightful way possible. It is in this way that long-termists working on global development can improve the tractability of the current threats and even ones that we haven’t considered yet. It is important to note that global development is not the only generalizable option and other efforts that are more resilient to the uncertainty of specific interventions might include things like electoral reform, improving institutional decision-making, and increasing international cooperation.

Importance

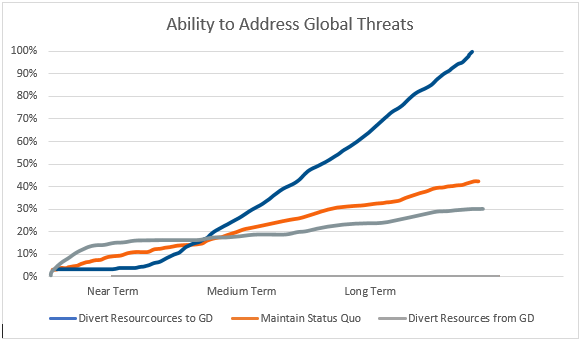

In the following graph I illustrate three counterfactual futures:

The orange line represents a maintenance of the status quo where global development and capacity of humanity to effectively address global threats proceed at present rates.

The grey line represents the extreme option of diverting all resources currently being used for development towards a dedicated worldwide effort to reduce threats to human extinction. In the near term this would likely increase capacity greatly but given the limited number of people living in circumstances where this kind of work would be feasible and limited political will to address these issues, the subsequent increase would come only from that privileged minority working outside of national strategic goals as opposed to an expanding group of people, supported by international prioritization.

The blue line represents the opposite extreme where we pause work explicitly targeting extinction risk and focus on development of a more equitable world where the abundance created by technological advances are supporting humanity in a much more efficient manner prior to re-engaging the effort to reduce specific extinction risks. This would theoretically lead to a superior ability to solve the rest of the world’s most pressing problems including reducing existential risks (and potentially move on to issues like interstellar colonization or yet unforeseen ways of ensuring a very long-term future for humanity).

The obvious drawback of the blue line is that there may be slightly less chance of it existing as we may all go extinct before those lines cross over but the drawback of the grey line is that it becomes less likely to exist at some point in the future. To be clear, I don’t believe either extreme would be a wise course of action and these examples are for illustrative/comparative purposes only. The idea is that there are probably some important trade-offs.

Expected value calculations could theoretically estimate the ideal balance of near term x-risk reduction vs. long-term x-risk reduction. That would be exceedingly complex and includes variables which I do not have the expertise to properly evaluate (but I hope someone in the future will make this a point of serious research). This line of reasoning raises the possibility that focusing too much on reducing specific x-risks now can ironically and counter-intuitively be a nearsighted effort which does not give enough weight to the importance of reducing risks that will come in the distant future. The generalizable capacity building interventions like global development are geared more towards the latter in expectation.

This is not a possibility that is unnoticed by people working on existential risk. Toby Ord wrote an excellent piece with FHI which cautioned that some existential risk effort was too specific and thereby “nearsighted”. The suggestions given there were to focus on “course setting, self-improvement and growth.” I realize that I am taking these comments out of the context that they were intended for but believe that the general principles which apply to individuals may be applicable to humanity generally as well. The work of course setting, self-improvement and growth on a global scale, seems to me, a fitting description of a long-termist’s approach to global development.

Conclusions

It is my belief that global development is unlikely to negatively impact the long-term future and if done thoughtfully, with a long-termist perspective, may have a significant positive impact on reducing existential risk. I also humbly submit the opinion that this approach may be an even more successful strategy for reducing x-risk than many of the risk-specific efforts to ensure that humanity has a long and happy future.

As concrete recommendations for improvement I propose the following:

- Shift away from short-termist poverty interventions towards objectives more aligned with core EA value of long-termism.

- Addition of resources for individual donors inclined to contribute to reducing global poverty in ways that also prioritize long-term future.

- Additional focus and research at the intersection between x-risk and global development.

I hope that at the very least, this shows the inter-relatedness between these two cause areas which hopefully will be interesting enough to some readers to promote greater collaborative efforts between these two silos of thought. I look forward to your feedback and future discussion on this important topic.

(These are my own personal opinions and do not reflect the views of the US Public Health Service or Loma Linda University)

Greg Lewis writes about this in his excellent post: "Beware of surprising and suspicious convergence":

I think this post already has a link to that excellent post in the disclaimer in the third section.

Yes that is a major risk with this kind of thing and I cited that article in the disclaimer. I think there is almost certainly a real convergence but the strength of that convergence is what is debatable. Finding the bits where these cause areas intersect may really be a great opportunity though which EA is uniquely capable of researching and making a positive impact. So it is good to be skeptical of the convenient convergence phenomenon but that shouldn’t make us blind to ways where real convergence may be a convenient opportunity to have an outsized impact.

Just a note that under the Sendai Process, UNDRR is now considering Xrisks, largely thanks to input from James Throup of ALLFED and Prof Virginia Murray, and will go on to consider cascading risks, sometimes called the "Boring Apocalypse" (ref EA Matthjis Maas).

I appreciate your post Brandon. I think there's a clear case that education and being able to exit survival level of poverty and knowing that your health and your children's education are secure enables people to focus on other things (demonstrated again in recent Basic Income research).

Development and poverty reduction is very helpful but perhaps not sufficient: response capacity and good leadership is also needed, as we have seen in the pandemic?

Just wanted to add the link and abstract to the boring apocalypses paper, for any readers who may be interested: Governing Boring Apocalypses: A new typology of existential vulnerabilities and exposures for existential risk research

(That's indeed just the abstract; not sure why it's three paragraphs long. Also, disclaimer that I haven't read beyond the abstract myself.)

Super cool to hear that UNDRR will be considering existential risks!

Are there any links to public statements or white papers or whatever mentioning that yet?

If not, could you say a little more about this new consideration might entail for their work?

(I'd also understand if it's too early days or if this info is somewhat sensitive for some reason.)

Yes, the US pandemic response in particular is evidence that the wealth of a country does not seem to be the most important factor in effective response to threats. Also, the “boring apocalypse“ scenario seems much more probable to me than any sort of “bang” or rapid extinction event and I think there is a lot that could be done in the realm of global development to help create a world more robust to that kind of slow burn.

I think additional research on this would be beneficial. This question is also a part of the Global Priorities Institute's research agenda.

Related questions the Global Priorities Institute is interested in:

This is great! I’m glad these things are at least on the agenda. I will be following with interest to see what comes of this.

Interesting point about the neglectedness of global development with an eye toward the long-term future. Could you say more about what that might look like?

It could go the other way, however, because some models indicate that work on AGI safety and alternative foods might be a cheaper way of saving lives in less-developed countries than bednets (though maybe not than promoting economic growth).

I think my point is that we don’t know all that much about what that would look like. I have my own theories but they may be completely off base because this research is fairly uncommon and neglected. I think economic growth may not even be the best metric for progress but maybe some derivative of the Gross National Happiness Index or something of that nature. I do think that there may be bidirectional benefit from focusing at the intersection of x-risk and global development. I love the work ALLFED is doing BTW!

Epistemic status: I've only spent perhaps 15 minutes thinking about these specific matters, though I've thought more about related things.

I'd guess that happiness levels (while of course intrinsically important) wouldn't be especially valuable as a metric of how well a global health/development intervention is reducing existential risks. I don't see a strong reason to believe increased happiness (at least from the current margin) leads to better handling of AI risk and biorisk. Happiness may correlate with x-risk reduction, but if so, it'd probably due to other variables affecting both of those variables.

Metrics that seem more useful to me might be things like:

The last two of those metrics might be "directly" important for existential risk reduction, but also might serve as a proxy for things like the first two metrics or other things we care about.

I also think well-being is not the ideal metric for what type of development would reduce x-risk either. When I mention the Gross Nation Happiness metric this is just one measure currently being used which actually includes things like good governance and environmental impact among many other things. My point was that growth in GDP is a poor measure of success and that creating a better metric of success might be a crucial step in improving the current system. I think a measure which attempts to quantify some of the things you mention would be wonderful to include in such a metric and would get the world thinking about how to improve those things. GNH is just one step better IMO than just seeking to maximize economic return. For more on GNH: https://ophi.org.uk/policy/national-policy/gross-national-happiness-index/

Oh, ok. I knew of "gross national happiness" as (1) a thing the Bhutan government talked about, and (2) a thing some people mention as more important than GDP without talking precisely about how GNH is measured or what the consequences of more GNH vs more GDP would be. (Those people were primarily social science teachers and textbook authors, from when I taught high school social science.)

I wasn't aware GNH had been conceptualised in a way that includes things quite distinct from happiness itself. I don't think the people I'd previously heard about it from were aware of that either. Knowing that makes me think GNH is more likely to be a useful metric for x-risk reduction, or at least that it's in the right direction, as you suggest.

At the same time, I feel that, in that case, GNH is quite a misleading term. (I'd say similar about the Happy Planet Index.) But that's a bit of a tangent, and not your fault (assuming you didn't moonlight as the king of Bhutan in 1979).

Thanks!

Great article! Congrats.

It may be argued that this century may be the most critical for global warming so lifting current people from poverty to a fuel-burning prosperity may be worse than leaving it to later on. In the future better technology may compensate for the fact that we would have more people to be lifted from poverty and into prosperity. For eg, prosperity may be less linked to fuel-burning then it is now or maybe we just made those geoengineering projects work so we can keep on burning oil like crazy. (I'm not defending any of this).

On empowering insufficiently benevolent people: I would need to better look at data but it seems many terrorists don't come from poor families but from middle-class somewhat well-educated backgrounds, many attending university. Maybe educating and lifting people from poverty may, on first, exacerbate this problem. However, it seems to me that the real issue here is religious fanaticism and other radical ideologies, so popular in universities, east or west. I really like the approach from Idea beyond borders on this issue - this project is backed by Pinker who is very found of EA movement and maybe EA should pay more attention to initiatives like that.

I already think technology is at a point where welfare does not have to depend on fossil fuel consumption. This is why the efforts to have low carbon or carbon neutral development like the Global Green New Deal and other international efforts are crucial. I don’t think the western world is a model to be followed as much as it is a warning of what not to do in many ways. But yeah, I think we are already at a place where development doesn’t have to require a larger carbon footprint, we may just lack the political willpower to implement those technologies at the scale required due to some perverse global economic incentives around that issue.

I share concerns about religious fundamentalism and radical ideology. I don’t think I’ve seen any data suggesting that development inherently makes these things worse though and my intuition tells me that rationality is more likely to thrive in a world with higher average welfare and/or decreased inequality.

A useful concept here might be that of an "environmental Kuznets curve":

There is both evidence for and against the EKC. I'm guessing the evidence varies for different aspects of environmental quality and between regions. I'm not an expert on this, but that Wikipedia section would probably be a good place for someone interested in the topic to start.

I think I broadly agree, but that it's also true that present-day welfare is cheaper if we use fossil fuels than low/no carbon fuels (if we're ignoring things like carbon taxes or renewables subsidies that were put in place specifically to address the externalities). I think carbon mitigation is well worth the price (including the price of enacting e.g. carbon taxes) when we consider future generations, and perhaps even when we consider present generations' entire lifespans (though I haven't looked into that). But there are some real tensions there, for people who are in practice focused on near-term effects.