What's the most cost-effective economic growth-boosting intervention? It's cat mascots. I just learned about Tama the calico cat (via @thatgoodnewsgirl on Instagram), who "gained fame for being a railway station master and operating officer at Kishi Station on the Kishigawa Line in Kinokawa, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan".

The career section of her Wikipedia page astounded me:

... (read more)Tama was born in Kinokawa, Wakayama, and was raised with a group of stray cats that used to live close to Kishi Station. They were regularly fed by passengers and by Toshiko Koyama, the informal station manager at the time.

The station was near closure in 2004 because of financial problems on the rail line. Around this time, Koyama adopted Tama. Eventually the decision to close the station was withdrawn after the citizens demanded that it stay open.[3] In April 2006, the newly formed Wakayama Electric Railway destaffed all stations on the Kishigawa Line to cut costs, and at the same time evicted the stray cats from their shelter to make way for new roads leading to the stations. Koyama pleaded with Mitsunobu Kojima, president of Wakayama Electric Railway, to allow the cats to live inside Kishi Station; Kojima

A few thoughts. First, it is a really cute story, and I'm glad you shared it. It feels very Japanese.

Second, marketing and tourism aren't often considered as major areas for economic development and growth (at least not in the popular press books I've read or the EA circles I've been in), but this is a simple little case study to demonstrate that having a mascot (or anything else that people like, from fancy buildings to locations tied to things people like) can drive economic activity. But it is also hard to predict in advance what will be a hit. I bet that lots of places have beautiful murals, cute animals, historical importance, lovely scenery, and similar attractions without having much of a positive return on investment. For me, the notable think about Tama's story is how little money was needed to add something special to the local station. A lot of investments related to tourism are far more expensive.

A final thought, one that maybe folks more versed in economics can help me with. Should we consider this an example of economic growth? Is this just shifting spending/consumption from one place to another? Would people who spent money to ride this train otherwise would have spent that money doing something else: riding a different train, visiting a park, etc.

I spent most of my early career as a data analyst in industry, which engendered in me a deep wariness of quantitative data sources and plumbing, and a neverending discomfort at how often others tended to just take them as given for input into consequential decision-making, even if at an intellectual level I knew their constraints and other priorities justified it and they were doing the best they could. ...and then I moved to global health applied research and realised that the data trustworthiness situation was so much worse I had to recalibrate a lot of expectations / intuitions.

In that regard I appreciate GiveWell's new guidance on burden note:

... (read more)Disease burden estimates, such as child mortality rates, are a key input in our cost-effectiveness analyses. Historically, for consistency and convenience, we've primarily relied on a single source for these estimates.

Going forward, we plan to consider multiple sources for burden estimates, apply a higher level of scrutiny to these estimates, and adjust for potential biases or inaccuracies, like we do when estimating other parameters in our models.

This change has already led to us making over $25m in additional gra

Counting people is hard. Here are some readings I've come across recently on this, collected in one place for my own edification:

- Oliver Kim's How Much Should We Trust Developing Country GDP? is full of sobering quotes. Here's one: "Hollowed out by years of state neglect, African statistical agencies are now often unable to conduct basic survey and sampling work... [e.g.] population figures [are] extrapolated from censuses that are decades-old". The GDP anecdotes are even more heartbreaking

- Have we vastly underestimated the total number of people on Earth? Quote: "Josias Láng-Ritter and his colleagues at Aalto University, Finland, were working to understand the extent to which dam construction projects caused people to be resettled, but while estimating populations, they kept getting vastly different numbers to official statistics. To investigate, they used data on 307 dam projects in 35 countries, including China, Brazil, Australia and Poland, all completed between 1980 and 2010, taking the number of people reported as resettled in each case as the population in that area prior to displacement. They then cross-checked these numbers against five major population datasets that

Buried deep in the PEPFAR Report's appendix - methodology section is a nice "introduction to global health programs" mini-article that also addresses some lay misconceptions about foreign aid and suggests a better way to think about it all in one go; it's a shame that most folks won't read it, so I'm reposting it here for ease of future reference.

... (read more)Introduction to Global Health Programs

Many people are skeptical of foreign aid and other attempts to help the global poor—and they’re right to be! A lot of foreign aid is poorly targeted, counterproductive, or simply a waste of money. From PlayPumps to TOMS shoes to One Laptop Per Child, the news is full of well-intentioned programs that had nowhere near the effect their boosters advertised. Many prominent experts, such as William Easterly and Angus Deaton, question whether foreign aid works at all.

Development economists, charity evaluators, and other specialists perform “program evaluations,” which ask questions like:

- Does the problem we’re trying to solve actually exist?

- Why does the problem exist?

- Is the program well-implemented?

- Is the program having the effect that we expected?

- Is the program too expensive? Can some other program get the s

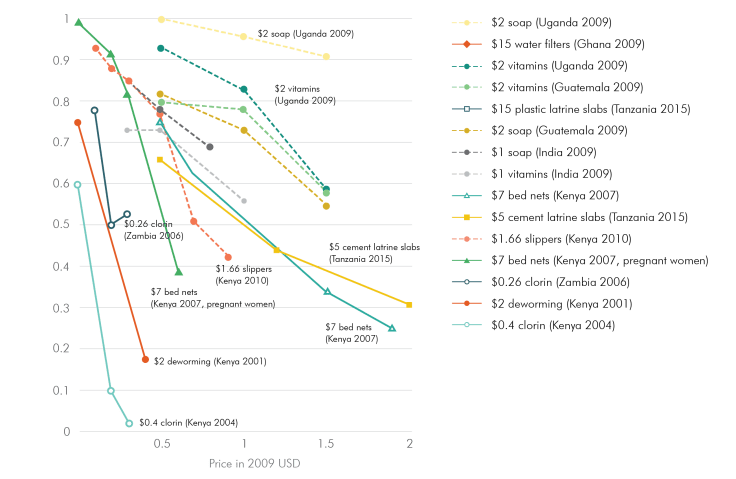

From Rachel Glennerster's old J-PAL blog post, a classic worth resharing: "charge for bednets or distribute them for free?"

... (read more)In 2000 there was an intense argument about whether malarial insecticide-treated bednets (ITNs) should be given out for free. Some argued that charging for bednets would massively reduce take-up by the poor. Others argued that if people don’t pay for something, they don’t value it and are less likely use it. It was an evidence-free argument at the time.

Then, a series of studies in many countries testing many different preventative health products showed that even a small increase in price led to a sharp decline in product take-up. Pricing did not help target the product to those who needed it most, and people were not more likely to use a product if they paid for it. This cleared the way for a massive increase in free bednet distribution (Dupas 2011 and Kremer and Glennerster 2011).

There was a dramatic increase in malaria bednet coverage between 2000 and 2015 in sub-Saharan Africa. At the same time, there was a massive fall in the number of malarial cases. In Nature, Bhatt and colleagues estimate that the vast majority of the decline in malarial cases is

I just learned that Trump signed an executive order last night withdrawing the US from the WHO; this is his second attempt to do so.

WHO thankfully weren't caught totally unprepared. Politico reports that last year they "launched an investment round seeking some $7 billion “to mobilize predictable and flexible resources from a broader base of donors” for the WHO’s core work between 2025 and 2028. As of late last year, the WHO said it had received commitments for at least half that amount".

Full text of the executive order below:

... (read more)WITHDRAWING THE UNITED STATES FROM THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION

By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered:

Section 1. Purpose. The United States noticed its withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2020 due to the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic that arose out of Wuhan, China, and other global health crises, its failure to adopt urgently needed reforms, and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states. In addition, the WHO continues to dema

Someone noted that at the rate of US GHD spending, this would cost ~12,000 counterfactual lives. A tremendous tragedy.

Striking paper by Anant Sudarshan and Eyal Frank (via Dylan Matthews at Vox Future Perfect) on the importance of vultures as a keystone species.

To quote the paper and newsletter — the basic story is that vultures are extraordinarily efficient scavengers, eating nearly all of a carcass less than an hour after finding it, and farmers in India historically relied on them to quickly remove livestock carcasses, so they functioned as a natural sanitation system in helping to control diseases that could otherwise be spread through the carcasses they consume. In 1994, farmers began using diclofenac to treat their livestock, due to the expiry of a patent long held by Novartis leading to the entry of cheap generic brands made by Indian companies. Diclofenac is a common painkiller, harmless to humans, but vultures develop kidney failure and die within weeks of digesting carrion with even small residues of it. Unfortunately this only came to light via research published a decade later in 2004, by which time the number of Indian vultures in the wild had tragically plummeted from tens of millions to just a few thousands today, the fastest for a bird species in recorded history and the larg... (read more)

This is a top-level comment compiling scattered notes on quantifying benefits / costs and related things, for my own benefit. Future notes will be comments under this one.

The purpose of this compilation is to essentially fact-post / perpetual-draft my way towards a more nuts-and-bolts understanding of the "what are the most effective interventions?" question, which is a different starting point than the usual "what are the most cost-effective?" one, a perspective shift primarily spurred by Justin Sandefur's case study on PEPFAR and a desire to better internalise what "big EA" might look like (as opposed to taking a scarcity mindset as given), albeit in a lazy undirected way: these notes are from references I encounter in the course of doing other work.

Past relevant notes:

- Global immunisation efforts have saved ~154 million lives and led to 10.2 billion full health years gained over the last 50 years, 95% of them children under-5, 2/3rds infants

- Tom Frieden likely helped saved tens of millions of lives by creating an international tobacco control initiative, and in his new role as CEO of Resolve to Save Lives is aiming to save 94 million more in 25 years

- Notes on Richard Parncutt

Martin Gould's Five insights from farm animal economics over at Open Phil's FAW newsletter points out that (quote) "blocking local factory farms can mean animals are farmed in worse conditions elsewhere":

... (read more)Consider the UK: Local groups celebrate blocking new chicken farms. But because UK chicken demand keeps growing — it rose 24% from 2012-2022 — the result of fewer new UK chicken farms is just that the UK imports more chicken: it almost doubled its chicken imports over the same time period. While most chicken imported into the UK comes from the EU, wh

#9 of Santi Ruiz's 50 thoughts on DOGE over at Statecraft caught my eye:

... (read more)Information silos are crazier than ever.

- For example, I’ve been privy to two parallel, heated debates about foreign aid over the past half-decade. People who work in foreign development (especially effective altruists) have engaged in a battle about the efficacy of various forms of foreign aid: what works best, what works less well, what doesn’t work at all, and how we can know.

- Meanwhile, right-wingers have spent much of the last decade (since the summer of 2020 in particular) doc

Many heads are more utilitarian than one by Anita Keshmirian et al is an interesting paper I found via Gwern's site. Gwern's summary of the key points:

- Collective consensual judgments made via group interactions were more utilitarian than individual judgments.

- Group discussion did not change the individual judgments indicating a normative conformity effect.

- Individuals consented to a group judgment that they did not necessarily buy into personally.

- Collectives were less stressed than individuals after responding to moral dilemmas.

- Interactions reduced aversive emotions (eg. stressed) associated with violation of moral norms.

Abstract:

... (read more)Moral judgments have a very prominent social nature, and in everyday life, they are continually shaped by discussions with others. Psychological investigations of these judgments, however, have rarely addressed the impact of social interactions.

To examine the role of social interaction on moral judgments within small groups, we had groups of 4 to 5 participants judge moral dilemmas first individually and privately, then collectively and interactively, and finally individually a second time. We employed both real-life and sacrificial moral dilemma

Curious what people think of Gwern Branwen's take that our moral circle has historically narrowed as well, not just expanded (so contra Singer), so we should probably just call it a shifting circle. His summary:

The “expanding circle” historical thesis ignores all instances in which modern ethics narrowed the set of beings to be morally regarded, often backing its exclusion by asserting their non-existence, and thus assumes its conclusion: where the circle is expanded, it’s highlighted as moral ‘progress’, and where it is narrowed, what is outside is simply defined away.

When one compares modern with ancient society, the religious differences are striking: almost every single supernatural entity (place, personage, or force) has been excluded from the circle of moral concern, where they used to be huge parts of the circle and one could almost say the entire circle. Further examples include estates, houses, fetuses, prisoners, and graves.

(I admittedly don't find his examples all that persuasive, probably because I'm already biased to only consider beings that can feel pleasure and suffering.)

What's the "so what"? Gwern:

... (read more)One of the most difficult aspects of any theory of moral prog

As someone predisposed to like modeling, the key takeaway I got from Justin Sandefur's Asterisk essay PEPFAR and the Costs of Cost-Benefit Analysis was this corrective reminder – emphasis mine, focusing on what changed my mind:

... (read more)Second, economists were stuck in an austerity mindset, in which global health funding priorities were zero-sum: $300 for a course of HIV drugs means fewer bed nets to fight malaria. But these trade-offs rarely materialized. The total budget envelope for global public health in the 2000s was not fixed. PEPFAR raised new money. That money was probably not fungible across policy alternatives. Instead, the Bush White House was able to sell a dramatic increase in America’s foreign aid budget by demonstrating that several billion dollars could, realistically, halt an epidemic that was killing more people than any other disease in the world.

...

A broader lesson here, perhaps, is about getting counterfactuals right. In comparative cost-effectiveness analysis, the counterfactual to AIDS treatment is the best possible alternative use of that money to save lives. In practice, the actual alternative might simply be the status quo, no PEPFAR, and a 0.1% reduction in

Pretty funny CGD blog post by Victoria Fan and Rachel Bonnifield: If the Global Health Donors Were Your Parents: A (Whimsical) Comparative Perspective. Quoting at length (with some reformatting):

... (read more)Navigating the global health funding landscape can be confusing even for global health veterans; there are scores of donors and multilateral funding mechanisms, each with its own particular structure, personality, and philosophy. For the uninitiated, PEPFAR, GAVI, PMI, WHO, the Global Fund, UNITAID, and the Gates Foundation can all appear obscure and intimidating.

Why did India's happiness ratings consistently drop so much over time even as its GDP per capita rose?

Epistemic status: confused. Haven't looked into this for more than a few minutes

My friend recently alerted me to an observation that puzzled him: this dynamic chart from Our World in Data's happiness and life satisfaction article showing how India's self-reported life satisfaction dropped an astounding -1.20 points (4.97 to 3.78) from 2011 to 2021, even as its GDP per capita rose +51% (I$4,374 to I$6,592 in 2017 prices):

(I included China for comparison to illustrate the sort of trajectory I expected to see for India.)

The sliding year scale on OWID's chart shows how this drop has been consistent and worsening over the years. This picture hasn't changed much recently: the most recent 2024 World Happiness Report reports a 4.05 rating averaged over the 3-year window 2021-23, only slightly above the 2021 rating.

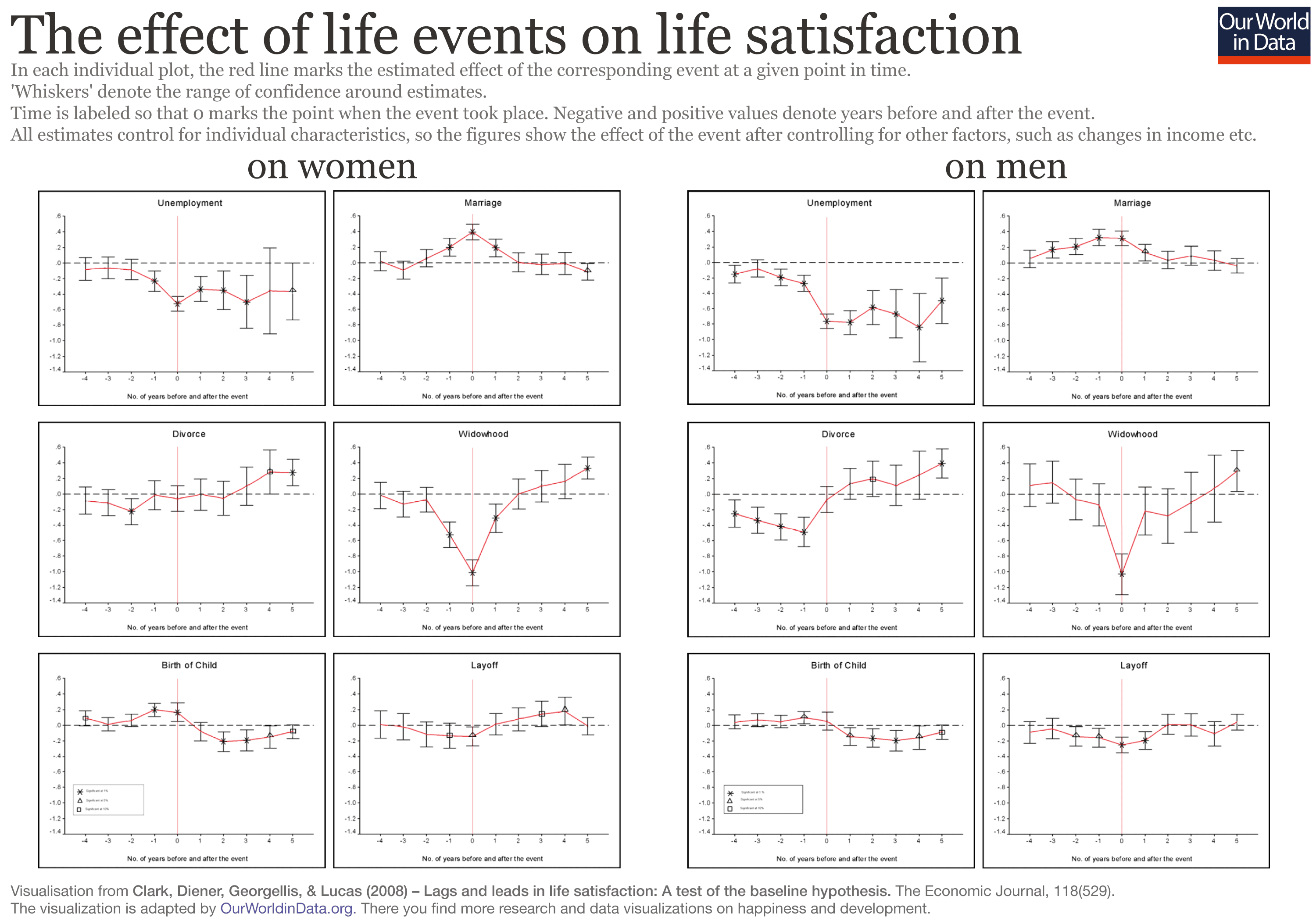

A -1.20 point drop is huge. For context, it's 10x(!) larger than the effect of doubling income at +0.12 LS points (Clarke et al 2018 p199, via HLI's report), and compares to major negative life events like widowhood and extended unemployment:

Gi... (read more)

Interesting! I think figure 2.1 here provides a partial answer. According to the FAQ:

"the sub-bars show the estimated extent to which each of the six factors (levels of GDP, life expectancy, generosity, social support, freedom, and corruption) is estimated to contribute to making life evaluations higher in each country than in Dystopia. Dystopia is a hypothetical country with values equal to the world’s lowest national averages for each of the six factors (see FAQs: What is Dystopia?). The sub-bars have no impact on the total score reported for each country but are just a way of explaining the implications of the model estimated in Table 2.1. People often ask why some countries rank higher than others—the sub-bars (including the residuals, which show what is not explained) attempt to answer that question."

India seems to score very low on social support, compared to similarly ranked countries.

I did some googling and found this, which shows the sub-factors over time for India. Looks like social support declined a lot, but is now increasing again.

I haven't checked whether it declined more than in other countries and, if it has, I'm not sure why it has.

Thank you for the pointer!

Your second link helped me refine my line of questioning / confusion. You're right that social support declined a lot, but the sum of the six key variables (GDP per capita, etc) still mostly trended upwards over time, huge covid dip aside, which is what I'd expect in the India development success story.

It's the dystopia residual that keeps dropping, from 2.275 - 1.83 = 0.445 in 2015 (i.e. Indians reported 0.445 points higher life satisfaction than you'd predict using the model) to 0.979 - 1.83 = -0.85, an absolute plummeting of life satisfaction across a sizeable fraction of the world population, that's for some reason not explained by the six key variables. Hm...

(please don't feel obliged to respond – I appreciate the link!)

I like Austin Vernon's idea for scaling CO2 direct air capture to 40 billion tons per year, i.e. matching our current annual CO2 emissions, using (extreme versions of) well-understood industrial processes.

... (read more)The proposed solution may not be the cheapest out there. Other ideas like ocean seeding or olivine weathering might be less expensive. But most of the science is understood, and it can scale quickly. I'd guess 100,000 workers could build enough sites to capture our 40 billion tons goal in a decade. The capital expenditure rate would be between $1 t

This WHO press release was a good reminder of the power of immunization – a new study forthcoming publication in The Lancet reports that (liberally quoting / paraphrasing the release)

- global immunization efforts have saved an estimated 154 million lives over the past 50 years, 146 million of them children under 5 and 101 million of them infants

- for each life saved through immunization, an average of 66 years of full health were gained – with a total of 10.2 billion full health years gained over the five decades

- measles vaccination accounted for 60% of t

I'm curious what people who're more familiar with infinite ethics think of Manheim & Sandberg's What is the upper limit of value?, in particular where they discuss infinite ethics (emphasis mine):

... (read more)Bostrom’s discussion of infinite ethics is premised on the moral relevance of physically inaccessible value. That is, it assumes that aggregative utilitarianism is over the full universe, rather than the accessible universe. This requires certain assumptions about the universe, as well as being premised on a variant of the incomparability argument that we dism

One of the more surprising things I learned from Karen Levy's 80K podcast interview on misaligned incentives in global development was how her experience directly contradicted a stereotype I had about for-profits vs nonprofits:

... (read more)Karen Levy: When I did Y Combinator, I expected it to be a really competitive environment: here you are in the private sector and it’s all about competition. And I was blown away by the level of collaboration that existed in that community — and frankly, in comparison to the nonprofit world, which can be competitive. People com

The following table is from Scott Alexander's post, which you should check out for the sources and (many, many) caveats.

... (read more)This table can’t tell you what your ethical duties are. I'm concerned it will make some people feel like whatever they do is just a drop in the bucket - all you have to do is spend 11,000 hours without air conditioning, and you'll have saved the same amount of carbon an F-35 burns on one airstrike! But I think the most important thing it could convince you of is that if you were previously planning on letting yourself be miserable t

I like John Salter's post on schlep blindness in EA (inspired by Paul Graham's eponymous essay), whose key takeaway is

Pay close attention to ideas that repel others people for non-impact related reasons, but not you. If you can get obsessed about something important that most people find horribly boring, you're uniquely well placed to make a big impact.

Unfortunately it's bereft of concrete examples. The closest to a shortlist he shares is in this comment:

... (read more)

- Horrible career moves e.g. investigating the corrupt practices of powerful EAs / Orgs

- Boring to mo

(Attention conservation notice: rambling in public)

A striking throwaway remark, given its context:

There is remarkably little evidence that evidence-based medicine leads to better health outcomes for patients, though this is absence of (good) evidence rather than (good) evidence of absence of effect.

It's striking given that this comes from this book on Thailand’s Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) (ch 1 pg 22), albeit perhaps understandable given the authors' stance that evidence is necessary but not sufficient to determine ... (read more)

Epistemic status: public attempt at self-deconfusion & not just stopping at knee-jerk skepticism

The recently published Cost-effectiveness of interventions for HIV/AIDS, malaria, syphilis, and tuberculosis in 128 countries: a meta-regression analysis (so recent it's listed as being published next month), in my understanding, aims to fill country-specific gaps in CEAs for all interventions in all countries for HIV/AIDS, malaria, syphilis, and tuberculosis, to help national decision-makers allocate resources effectively – to a first approximation I think ... (read more)

I just learned about Tom Frieden via Vadim Albinsky's writeup Resolve to Save Lives Trans Fat Program for Founders Pledge. His impact in sheer lives saved is astounding, and I'm embarrassed I didn't know about him before:

... (read more)The CEO of RTSL, Tom Frieden, likely prevented tens of millions of deaths by creating an international tobacco control initiative in a prior role that may have been much more cost effective than most of our top recommended charities. ...

We believe that by leveraging his influence with governments, and the relatively low cost of advoc

[Question] How should we think about the decision relevance of models estimating p(doom)?

(Epistemic status: confused & dissatisfied by what I've seen published, but haven't spent more than a few hours looking. Question motivated by Open Philanthropy's AI Worldviews Contest; this comment thread asking how OP updated reminded me of my dissatisfaction. I've asked this before on LW but got no response; curious to retry, hence repost)

To illustrate what I mean, switching from p(doom) to timelines:

- The recent post AGI Timelines in Governance: Diffe

Some notes from trying out Rethink Priorities' new cross-cause cost-effectiveness model (CCM) from their post, for personal reference:

Cost-effectiveness in DALYs per $1k (90% CI) / % of simulation results with positive outcomes - negative outcomes - no effects / alternative weightings of cost-eff under different risk aversion profiles and weighting schemes in weighted DALYs per $1k, min to max values

- GHD:

- US govt GHD: 1 (range: 0.85 - 1.22) / 100% positive / risk 1 - 1

- Cash: 1.7 (range 1.1 - 2.5) / 100% positive / risk 1 - 2

- GW bar: 21 (range: 11 -

The 1,000-ton rule is Richard Parncutt's suggestion for reframing the political message of the severity of global warming in particularly vivid human rights terms; it says that someone in the next century or two is prematurely killed every time humanity burns 1,000 tons of carbon.

I came across this paper while (in the spirit of Nuno's suggestion) trying to figure out the 'moral cost of climate change' so to speak, driven by my annoyance that e.g. climate charity BOTECs reported $ per ton of CO2-eq averted in contrast to (say) the $ per death averted ... (read more)

Notes from Ozy Brennan's On capabilitarianism

- Martha Nussbaum's first-draft list of central capabilities (for humans)

- Life

- Bodily health

- Bodily integrity

- Senses, Imagination, and Thought

- Emotions

- Practical reason

- Affiliation

- Other species

- Play

- Control over political & material environment

- the Five Freedoms (for animals)

- Freedom from hunger and thirst

- Freedom from discomfort

- Freedom from pain, injury, and disease

- Freedom to express normal behavior

- Freedom from fear and distress

I thought I had mostly internalized the heavy-tailed worldview from a life-guiding perspective, but reading Ben Kuhn's searching for outliers made me realize I hadn't. So here are some summarized reminders for posterity:

- Key idea: lots of important things in life generated by multiplicative processes resulting in heavy-tailed distributions – jobs, employees / colleagues, ideas, romantic relationships, success in business / investing / philanthropy, how useful it is to try new activities

- Decision relevance to living better, i.e. what Ben thinks

From Richard Y Chappell's post Theory-Driven Applied Ethics, answering "what is there for the applied ethicist to do, that could be philosophically interesting?", emphasis mine:

... (read more)A better option may be to appeal to mid-level principles likely to be shared by a wide range of moral theories. Indeed, I think much of the best work in applied ethics can be understood along these lines. The mid-level principles may be supported by vivid thought experiments (e.g. Thomson’s violinist, or Singer’s pond), but these hypothetical scenarios are taken to be practically il

Michael Dickens' 2016 post Evaluation Frameworks (or: When Importance / Neglectedness / Tractability Doesn't Apply) makes the following point I think is useful to keep in mind as a corrective:

... (read more)INT has its uses, but I believe many people over-apply it.

Generally speaking (with some exceptions), people don’t choose between causes, they choose between interventions. That is, they don’t prioritize broad focus areas like global poverty or immigration reform. Instead, they choose to support specific interventions such as distributing deworming treatments or

List of charities providing humanitarian assistance in the Israel-Hamas war mentioned in response to this request, for posterity and ease of reference:

- Physicians for Human Rights Israel (2022 Impact Report, response to the current crises)

- Al Mezan Centre for Human Rights

- Palestinian Centre for Human Rights

- Charity Navigator's list has 18 charities, of which only Global Empowerment Mission Inc. is rated on 'impact & results'

Just came across Max Dalton's 2014 writeup Estimating the cost-effectiveness of research into neglected diseases, part of Owen Cotton-Barratt's project on estimating cost-effectiveness of research and similar activities. Some things that stood out to me:

- High-level takeaways

- ~100x 95% CI range (mostly from estimates of total current funding to date, and difficulty of continuing with research), so figures below can't really argue for change in priorities so much as compel further research

- This uncertainty is a lower bound, including only statistical unce

- ~100x 95% CI range (mostly from estimates of total current funding to date, and difficulty of continuing with research), so figures below can't really argue for change in priorities so much as compel further research

The following is a collection of long quotes from Ozy Brennan's post On John Woolman (which I stumbled upon via Aaron Gertler) that spoke to me. Woolman was clearly what David Chapman would call mission-oriented with respect to meaning of and purpose in life; Chapman argues instead for what he calls "enjoyable usefulness", which is I think healthier in ~every way ... it just doesn't resonate. All bolded text is my own emphasis, not Ozy's.

... (read more)As a child, Woolman experienced a moment of moral awakening: ... [anecdote]

This anecdote epitomizes the two driving forc

I'm curious what people who're more familiar with infinite ethics think of Manheim & Sandberg's What is the upper limit of value?, in particular where they discuss infinite ethics (emphasis mine):

I first read their paper a few years ago and found their arguments for the finiteness of value persuasive, as well as their collectively-exhaustive responses in section 4 to possible objections. So ever since then I've been admittedly confused by claims that the problems of infinite ethics still warrant concern w.r.t. ethical decision-making (e.g. I don't really buy Joe Carlsmith's arguments for acknowledging that infinities matter in this context, same for Toby Ord's discussion in a recent 80K podcast). What am I missing?

Much appreciated, thanks again Vasco.