Cross-posted to LessWrong.

Summary

- History’s most destructive ideologies—like Nazism, totalitarian communism, and religious fundamentalism—exhibited remarkably similar characteristics:

- epistemic and moral certainty

- extreme tribalism dividing humanity into a sacred “us” and an evil “them”

- a willingness to use whatever means necessary, including brutal violence.

- Such ideological fanaticism was a major driver of eight of the ten greatest atrocities since 1800, including the Taiping Rebellion, World War II, and the regimes of Stalin, Mao, and Hitler.

- We focus on ideological fanaticism over related concepts like totalitarianism partly because it better captures terminal preferences, which plausibly matter most as we approach superintelligent AI and technological maturity.

- Ideological fanaticism is considerably less influential than in the past, controlling only a small fraction of world GDP. Yet at least hundreds of millions still hold fanatical views, many regimes exhibit concerning ideological tendencies, and the past two decades have seen widespread democratic backsliding.

- The long-term influence of ideological fanaticism is uncertain. Fanaticism faces many disadvantages including a weak starting position, poor epistemics, and difficulty assembling broad coalitions. But it benefits from greater willingness to use extreme measures, fervent mass followings, and a historical tendency to survive and even thrive amid technological and societal upheaval. Beyond complete victory or defeat, multipolarity may persist indefinitely, with fanatics permanently controlling a non-trivial fraction of the universe, potentially using superintelligent AI to entrench their rule.

- Ideological fanaticism increases existential risks and risks of astronomical suffering through multiple mutually-reinforcing pathways.

- Ideological fanaticism exacerbates most common causes of war. Fanatics' sacred values and outgroup hostility often preclude compromise, while their irrational overconfidence and differential commitment credibility make bargaining failures more likely. Fanatics may even welcome conflict, rather than viewing it as a costly last resort.

- Fanatical retributivism may lead to astronomical suffering. In our survey of 1,084 people, 11–14% in the US, UK, and Pakistan agreed that if hell didn't exist, we should create it to punish evil people with extreme suffering forever, and separately selected 'forever' when asked how long evil people should suffer unbearable pain, while also stating that at least 1% of humanity deserves this fate. Rates ranged from 19–25% in China, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Similar questions showed roughly comparable patterns. Advanced AI could enable fanatics to actually instantiate such preferences.

- Certain of their righteousness, fanatics resist further reflection and seek to lock in their current values, which threatens long-reflection-style proposals that envision humanity carefully deliberating on how to achieve its potential. Viewing compromise and cooperation as betrayal, fanatics also seem more likely to oppose moral trade and use hostile bargaining tactics. Their intolerant ‘fussy’ preferences may regard almost all configurations of matter as immoral, including those containing vast flourishing, potentially resulting in astronomical waste.

- AI intent alignment alone won't help if the human principal is fanatical or malevolent: an AI aligned with Stalin probably won't usher in utopia. Fanatics may reflectively endorse their existing values, even after preference idealization. The worst futures may therefore arise from misuse of intent-aligned AI by ideological fanatics, rather than from misaligned AI.

- Ideological fanaticism also poses other risks, including extreme optimization and differential intellectual regress.

- Most relevant interventions, while not novel, fall into two overlapping categories.

- Political and societal interventions include strengthening and safeguarding liberal democracies, reducing political polarization, promoting anti-fanatical principles like classical liberalism, and fostering international cooperation.

- AI-related interventions appear higher-leverage. Compute governance and information security can reduce the likelihood that transformative AI falls into the hands of fanatical and malevolent actors. Preventing AI-enabled coups could be particularly important given such actors' propensity for power grabs. Other promising interventions include proactively using AI to improve epistemics at scale, developing fanaticism-resistant post-AGI governance frameworks, and making transformative AIs themselves less fanatical—e.g., by guiding their character towards wisdom and benevolence.

What do we mean by ideological fanaticism?

Consider some of history’s worst atrocities. In the Holocaust, the Nazi regime constructed an industrial apparatus to systematically exterminate six million Jews and others deemed 'subhuman'. During the Great Purge, Stalin's secret police tortured hundreds of thousands until they confessed to fictitious acts of treason, before executing them. A century earlier, the Taiping Rebellion claimed over twenty million lives as followers of a self-proclaimed messiah waged a holy war to cleanse the world of 'demons'.

These and many other horrors were substantially driven by three types of fanatical ideologies: fascist ethno-nationalism, totalitarian communism, and religious fundamentalism. In fact, these three fanatical ideologies were arguably responsible for the majority of deaths from mass violence since 1800, as we explore below.

While the specific beliefs of these and other destructive ideologies have varied dramatically, the underlying patterns in thought, emotion, and behavior were remarkably similar. Numerous frameworks could summarize these dynamics, but we focus on three mutually reinforcing characteristics—the fanatical triad—because they arise in virtually all relevant cases while remaining simple and memorable:

- Absolute epistemic and moral certainty;

- Manichean tribalism, where humanity is divided into a sacred 'us' and an irredeemably evil 'them';

- A willingness to use any means necessary, including brutal violence.

While the term “fanatical triad” is our own, each of the three characteristics draws upon well-established academic concepts, including dogmatism, tribalism, and totalitarianism. (See Appendix A for an extensive overview connecting each “fanatical triad” component to existing scholarship and historical case studies.)

Ideological fanaticism closely resembles 'extremism', but that term typically describes anti-establishment movements at the periphery of society (Bötticher, 2017).[1] In contrast, we are also concerned with the risk of fanatical ideologies commanding mainstream adherence and capturing state power. 'Fanaticism' also better connotes the zealous, uncompromising hatred we wish to emphasize. Our term should not be confused with ‘Pascalian’ expected value fanaticism.[2]

One overarching characteristic of the fanatical worldview is black-and-white thinking (good vs. evil, us vs. them) with no room for nuance. Let's not make the same mistake. Like most phenomena, ideological fanaticism exists on a continuum. Furthest from fanaticism are those enlightened few who, following reason and evidence, act with benevolence towards all. A vast middle ground is occupied by religious traditionalists, hyper-partisan activists, conspiracy theorists, and many others. Indeed, a mild form of ideological fanaticism is arguably human nature: we are all somewhat prone to overconfidence, motivated reasoning, and tribalistic in-group favoritism and outgroup discrimination (e.g., Kunda, 1990; Diehl, 1990; Hewstone et al., 2002).[3] But ideological fanatics take such traits to extremes.

I. Dogmatic certainty: epistemic and moral lock-in

The most ardent fanatics are utterly convinced they have found the one infallible authority in possession of ultimate truth and righteousness; they are textbook dogmatists (Rokeach, 1960). For religious fundamentalists, this is usually a holy book containing the divine revelation of God and his prophets. For Nazis, it was Hitler's Führerprinzip (Leader Principle), codified by Rudolf Hess’s declaration that “the Führer is always right”. Similarly, many communist revolutionaries essentially placed absolute faith in foundational texts like Marx’s Das Kapital, or in the Party itself (Montefiore, 2007). “Angkar is an organization that cannot make mistakes” was a key slogan of the Khmer Rouge.[4]

For the fanatic, any doubt or deviation from these dogmas is not only wrong but evil, culminating in a total “soldier mindset” which defends the pre-existing ideology at all costs (Galef, 2021). This necessitates abandoning even the most basic form of empiricism by "rejecting the evidence of one’s own eyes and ears", to paraphrase Orwell.[5] The fanatic is thus essentially incorrigible and has no epistemic or moral uncertainty, even in the face of widespread opposition (Gollwitzer et al., 2022).[6]

II. Manichean tribalism: total devotion to us, total hatred for them

Building on tribalistic instincts innate to human nature (Clark et al., 2019), such dogmatic certainty both reinforces and is reinforced by an extreme form of “Manichean tribalism”, which views the world as a cosmic conflict between good and evil.[7] Examples include the racial struggle between ‘Aryans’ and ‘inferior’ races (Nazism), the revolutionary struggle against class enemies (communism), or the spiritual battle between God and the forces of Satan (religious fundamentalism).

As the fanatic’s in-group and ideology become their sole source of belonging and meaning, their individual identity fuses with the collective, resulting in all-consuming devotion to the cause and submission to its leaders[8] (Katsafanas, 2022b; Varmann et al., 2024). This is often further amplified through group dynamics, with members outbidding each other to prove their loyalty by embracing increasingly extreme views and punishing the slightest dissent. The most devoted fanatics eagerly die for the cause, as seen with Japanese kamikaze pilots or religious suicide bombers (Atran & Ginges, 2015). Nazism, for instance, was anchored in “uncritical loyalty” to Hitler (Hess, 1934) and oaths pledging unconditional “obedience unto death”. Similarly, millions of communists were true believers, exemplified by the Red Guards who pledged to “defend Chairman Mao and his revolution to the death” (Chang, 2008; Dikötter, 2016).

Fueling this extreme devotion is an equally intense hatred and resentment of a demonized outgroup (Szanto, 2022; Katsafanas, 2022a). This outgroup is often expansive, potentially including anyone merely disagreeing with a subset of the ideology’s claims—such as Stalin executing Trotskyists or ISIS murdering other Muslims for insufficient piety. Driven in part by paranoia and conspiratorial thinking, fanatics often scapegoat this outgroup as the source of nearly all problems. Typically, this enemy is believed to deserve extreme punishment, ranging from torture and systematic extermination, to religious visions of hell, where nonbelievers are damned to eternal torment.

Supercharging moral instincts relating to purity and disgust (cf. Haidt, 2012), fanatics may reject all compromise as betrayal of their inviolable, sacred values (Tetlock, 2003), often resulting in a zero-sum mentality where the only acceptable outcome is the ideology’s total victory.

III. Unconstrained violence: any means necessary

“Any violence which does not spring from a spiritual base, will be wavering and uncertain. It lacks the stability which can only rest in a fanatical worldview.”

- Adolf Hitler, 1925

Most humans hesitate to commit violence due to various guardrails like instinctive harm aversion, social norms, empathy, and compassion for others’ suffering. To further reinforce these better angels of our nature, humanity painstakingly developed complex moral and institutional frameworks, like virtue ethics, deontology, separation of powers, and the rule of law.[9]

Fanatics toss all that malarkey out the window. They are certain that they champion the forces of righteousness in a total war against evil. Their victory will redeem this 'vile world' (Stankov et al., 2010) and usher in utopia, whether it be a perfect communist society, a Thousand-Year Reich, or religious paradise. These existential stakes justify any means necessary, no matter how extreme.

In fact, some fanatics even invert the entire moral paradigm, glorifying what others find most abhorrent. Compassion, honesty, and moderation[10] become weakness; law-breaking, deceit, and violence become virtues.[11] ISIS fighters, for instance, filmed themselves burning their victims alive and proudly distributed the footage.

With enough power, fanatics can achieve their vision: totalitarian control over society that eliminates individual liberty and forces everyone to conform to their ideology—using censorship, propaganda, and even mass murder if necessary (Arendt, 1951).[12]

Fanaticism as a multidimensional continuum

Ideological fanaticism is not just a single sliding scale. Rather, it is multidimensional, that is, people can exhibit different levels of each fanatical triad component. The most dangerous form of ideological fanaticism requires elevated levels of all three characteristics. A hypothetical ‘Bayesian Nazi’, for instance, would lack absolute certainty and thus remain open to changing his mind. Similarly, without Manichean hatred, there is no motivation for mass harm, and without a willingness to use violence, even the most hateful beliefs remain inert.

Nor are fanatical movements monolithic.[13] While their leaders often were malignant narcissists, their followers are frequently ordinary people desperately seeking meaning and certainty in a chaotic, disappointing world (Hoffer, 1951; Kruglanski et al., 2014; Tietjen, 2023). Not all are true believers, either: some merely conform to group pressure, others are cynical opportunists, and many fall somewhere in between.[14] Many fanatics are capable of eventual reform, so we should not demonize them as irredeemably evil.

Finally, though related, we shouldn't confuse fanaticism with strong moral convictions (Skitka et al., 2021).[15] Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, held radically progressive views for his time, but remained open to evidence, sought coalition-building across racial lines, and was explicitly opposed to violence.

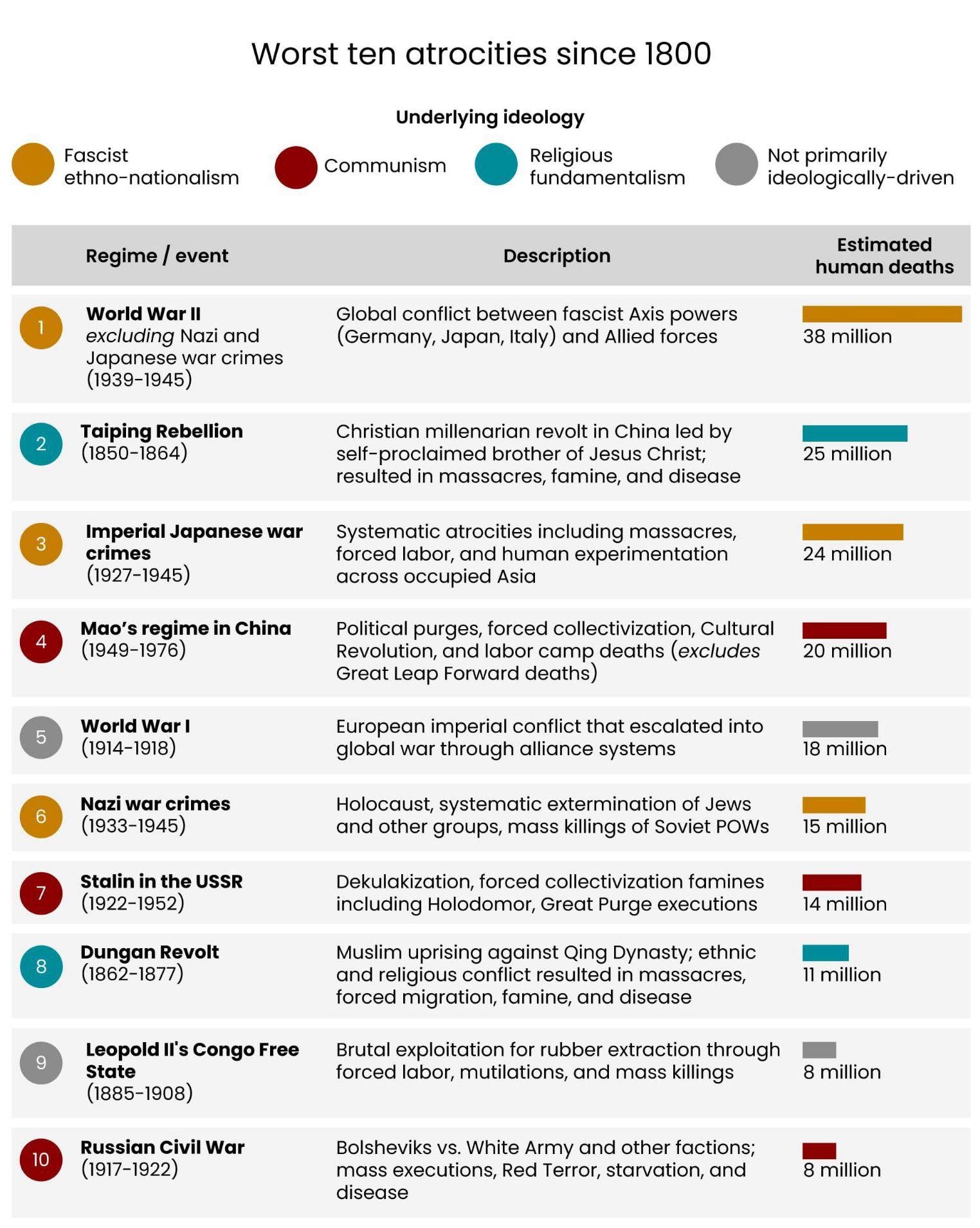

Ideological fanaticism drove most of recent history's worst atrocities

One reason we fear ideological fanaticism may pose substantial future risks is its grim historical track record. Ideological fanaticism seems to have been a major driver of eight of the ten worst atrocities since 1800.[16] In the following table, we only included events involving intentional[17] mass killing, excluding accidental famines and pandemics[18], for reasons discussed below.

This table is more informative than it may appear, as atrocity deaths follow a heavy-tailed distribution: of the 116 events since 1800 with death tolls exceeding 100,000 (totaling 266 million deaths), the ten worst atrocities alone account for 181 million deaths, or 68% of the total, and thus provide disproportionate explanatory value.

To be clear, these death toll estimates are uncertain (especially for the Dungan Revolt). We also made several debatable judgment calls regarding timeframe, categorization, and grouping (e.g., WWII could be one entry instead of being split into three). However, we're quite confident that our core finding is robust: ideological fanaticism contributed to the majority of deaths from mass violence since 1800.[19]

See Appendix B for extensive discussion of our methodology and other atrocities that didn't make the top ten. Three omissions stand out for their scale and horror: the Atlantic slave trade and Arab/Islamic slave trade each killed over 15 million people, but mostly before 1800. For various methodological and pragmatic reasons, we also excluded systematic killings of animals like factory farming, which kills hundreds of billions of animals annually—arguably the largest moral catastrophe of our time.

Of course, no single factor fully explains any historical atrocity. In addition to ideological fanaticism, other crucial causes and risk factors include political and economic instability (e.g., Weimar Germany), power-seeking and competition between individuals and groups (present in essentially all atrocities), inequality and exploitation (e.g., in Congo Free State), historical grievances, and individual leaders' personalities.[20] Moreover, these factors often interact with ideological fanaticism in mutually reinforcing ways: political and economic instability, for instance, make fanatical ideologies more appealing, and fanatical ideologies often further increase economic and political chaos.

Overall, for eight of the ten atrocities, our sense is that ideological fanaticism is at least among the handful of most important causal factors.[21] Even the two non-fanatical entries in our table—Leopold's Congo (primarily driven by greed) and World War I (primarily geopolitical competition)—were at least partly driven by forms of ideological fanaticism: colonial racism and fervent nationalism, respectively.

Death tolls don’t capture all harm

While deaths correlate with many other harms, such as deprivation, oppression, and torture,[22] extreme suffering can occur even when death tolls are relatively low. We nonetheless chose deaths as our metric because they are easily measurable—certainly more so than trying to calculate counterfactual net changes in quality-adjusted life years across poorly-documented historical periods.

Consider North Korea. This totalitarian regime has been responsible for "only" a few hundred thousand deaths in recent decades. Yet the lives of the vast majority of its 26 million inhabitants are filled with misery. Most are extremely poor; nearly half are malnourished. From early childhood, citizens are indoctrinated and denied basic freedoms of movement and information. To crush dissent, the regime operates a network of political prison camps where forced labor, torture, physical abuse, and summary executions are standard practice. The entire population is essentially a captive workforce, terrorized by the constant threat of violence and imprisonment.

In contrast, South Koreans enjoy vastly greater freedom and are more than 20 times wealthier. The differences that have emerged since the two countries split in the mid-20th century serve almost as a natural experiment demonstrating the power of ideological fanaticism (among other factors[23]) to inflict immense suffering, even when it doesn't result in millions of violent deaths.

Intentional versus natural or accidental harm

We focus on intentional deaths because they are most revealing of terminal preferences, which in turn are most predictive of future harm.

Intentional deaths are most revealing of terminal preferences: Had we included all deaths, our table would be dominated by age-related and infectious diseases, accidents, and starvation; categories that tell us little about intentions. This distinction also reflects common moral intuitions and the law: murder is worse than manslaughter partly because the former reveals intentionality (“malice aforethought”) and is much more predictive of future harm.

Terminal preferences are more predictive of future harm: From a longtermist perspective, the distinction between intentional and non-intentional harm is even more important. If civilization survives for long enough, continued scientific progress will likely lead to the invention of many consequential technologies—like superintelligent AI, advanced spaceflight, or nanotechnology. A civilization at ‘technological maturity’[24] would have tremendous control over the universe, so outcomes might become increasingly determined by the values of powerful agents, rather than by natural processes or unintended consequences. We can already observe early signs of this trajectory: deaths from infectious diseases and starvation, for instance, have decreased dramatically since 1800, largely due to humanity’s increasing technological capabilities. Thus, while natural and accidental harms still dominate at present, intentional harm will plausibly become the dominant source of future harm. (For a related but more complicated categorization, see also the distinction between agential, incidental, and natural harm[25].)

Why emphasize ideological fanaticism over political systems like totalitarianism?

Most previous discussions of socio-political existential risk factors and historical atrocities have tended to focus on concepts like (stable) totalitarianism (e.g., Arendt, 1951; Caplan, 2008; Clare, 2025), autocracy (Applebaum, 2024), authoritarianism (e.g., MacAskill & Moorhouse, 2025; Aird, 2021; Adorno, 1950), and safeguarding democracy (e.g., Koehler, 2022; Garfinkel, 2021; Yelnats, 2024)[26]. So why focus on ideological fanaticism instead of these more established concepts?

One major difference is that the above concepts all primarily describe political systems. We can view these on a continuum ranging from open to closed societies (Popper, 1945). Following Linz (2000), liberal democracies occupy the ‘open’ end of this spectrum—featuring competitive elections, civil liberties, and institutional checks on power. Authoritarianism occupies the middle ground, concentrating power in a single leader or party while tolerating limited private autonomy. Totalitarianism, such as in Stalin's USSR or wartime Nazi Germany, represents the ‘closed’ endpoint: authoritarianism plus complete ideological control, mass mobilization, and the elimination of almost all private life. While all totalitarian regimes are necessarily authoritarian, most authoritarian regimes never slide all the way down this spectrum to totalitarianism.

In contrast, our focus is on the underlying mindset and dangerous terminal values that characterize ideological fanatics.[27] As we'll argue, these factors may be more important from a longtermist perspective[28] because they i) can create and change political systems and, ii) pose risks that may emerge independently of specific forms of government, especially with AGI. Therefore, although there is substantial overlap between our approach and prior work (especially on totalitarianism[29]), we believe that the lens of ideological fanaticism is nevertheless valuable.

Fanatical and totalitarian regimes have caused far more harm than all other regime types

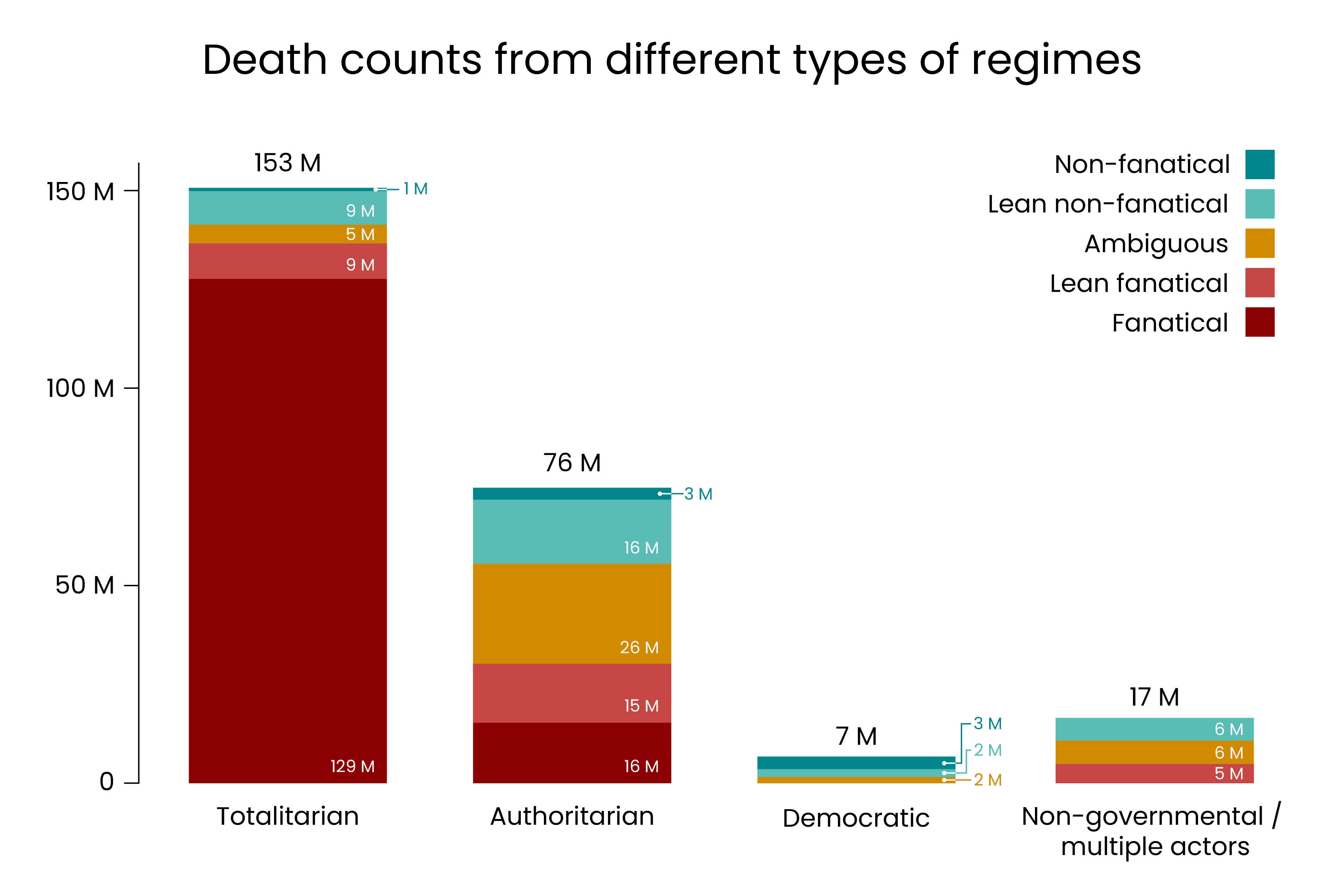

First, let’s ground our discussion in empirical data. We analyzed deaths from mass violence since 1800 by both regime type (totalitarian, authoritarian, democratic, non-governmental) and motivation (fanatical vs. non-fanatical):

History is messy and we aren’t historians, so we remain uncertain about many of our classifications—see here for our data, reasoning and methodology.[30] That said, this data suggests that we should be most concerned with totalitarianism and ideological fanaticism (most commonly in combination), as these were involved in the majority of all deaths from mass violence:[31] Totalitarian regimes accounted for 60% of all deaths (153M), while fanatical actors across all regime types accounted for 69% of total deaths (174M). Among authoritarian regimes, those driven by fanatical ideologies were likewise disproportionately destructive. Overall, non-fanatical actors were responsible for only 16% of total deaths (40M) and democracies for less than 3%.

Authoritarianism as a risk factor

Of course, we shouldn't ignore authoritarianism, which still accounted for 30% of all deaths (76m). Authoritarianism is also a key risk factor for totalitarianism, whereas democratic institutions serve as protective safeguards. Moving from authoritarianism to totalitarianism is comparatively easy: it would primarily require the autocrat (and perhaps some key members of the ruling elite) to strengthen the machinery for centralized control that is already in place. In contrast, transforming a democracy into a totalitarian state is a much more arduous undertaking. It requires dismantling an entire system of formal checks and balances as well as subverting democratic norms and public expectations of personal liberty.

Values change political systems: Ideological fanatics seek totalitarianism, not democracy

As our data shows, the overlap between totalitarianism and ideological fanaticism is substantial: of the 174M deaths caused by fanatical actors, almost 80% (138M) came from totalitarian regimes. So why not drop the fanaticism lens and focus only on totalitarianism? One reason is that ideological fanaticism is plausibly causally upstream: fanatics seek to create totalitarian political systems, more so than the reverse.

Consider the historical evidence. It seems clear that Hitler, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao[32]—and the fanatical ideologies they championed—were (among many other factors) major causal forces behind the creation of history's worst totalitarian regimes: Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and Maoist China. Crucially, all of these individuals were likely ideological fanatics years before seizing power. Hitler already exhibited the fanatical triad in Mein Kampf, published almost a decade before rising to power (1925): absolute certainty about racial theories, Manichean division of humanity into superior Aryans versus subhuman enemies, and explicit advocacy for violence. Lenin declared that "the Marxist doctrine is omnipotent because it is true" (1913), and advocated "a desperate, bloody war of extermination" (1906). Mao likewise demonstrated dogmatic certainty and embraced violence as necessary for revolutionary transformation long before gaining power. The totalitarian regimes they built were consequences of these pre-existing convictions.

This pattern isn't coincidental because ideological fanatics require totalitarian systems to achieve their vision. If you believe that a large portion of humanity is irredeemably evil and deserves extreme punishment or extermination, granting them political rights, personal liberty, and equal standing before the law becomes morally abhorrent. Ideological fanaticism and democratic principles are therefore structurally incompatible.[33] Empirical evidence supports such theoretical arguments. Ideological extremists (on both the left and the right) show less support for democracy[34] (Torcal & Magalhães, 2022) and are more likely to endorse authoritarian policies (Manson, 2020).[35]

Terminal values may matter independently of political systems, especially with AGI

Probably even more importantly, the mindset of ideological fanatics seems to play a major role for many of the long-term risks we’re most concerned about. As we’ll discuss later, political systems alone don’t fully explain irrationality or sacred values as major causes of war. Nor would they explain acts of torture motivated by fanatical retributivism, value lock-in threatening a long reflection, or insatiable moral ambitions.

Historically, a single human or small groups of humans couldn’t cause much harm unless they were in control of a state, but forthcoming technologies like transformative AI could drastically change this: a single fanatical human (or a small group) in control of superintelligent intent-aligned AI—or a superintelligent misaligned AI with fanatical values—could potentially amass enormous power and cause astronomical harm. This is possible even in a world in which totalitarian or other tyrannical systems of government no longer exist. The key issue is that sufficiently powerful technology can decouple capacity for harm from state control.

Fanaticism’s connection to malevolence (dark personality traits)

The threat posed by malevolent actors—our shorthand to refer to individuals with elevated dark traits like narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, or sadism—is related to but distinct from the risks posed by ideological fanatics. Not all fanatics have highly elevated dark traits and many commit horrific acts because of sincere moral convictions.[36] Conversely, many malevolent individuals weren’t ideological fanatics, e.g., serial killers like Ted Bundy. One key difference is that many ideological fanatics are willing to sacrifice and even die for their cause, while malevolent individuals are generally self-centered and egoistic.

However, ideological fanaticism and malevolence do have considerable overlap:

- Elevated dark tetrad traits make one more susceptible to ideological fanaticism. For instance, psychopaths, malignant narcissists, or sadists are naturally more inclined to feel total hatred for their enemies and commit acts of brutal violence. In fact, those with elevated dark traits may be attracted to belief systems that provide justifications for such actions. Empirical research shows that dark traits are associated with increased support for extremist ideologies.

Relatedly, the leaders of fanatical ideologies almost always exhibit highly elevated dark traits (Stalin, Mao, Hitler, Pol Pot, etc.). Some of these traits, especially narcissism, plausibly drive such figures to invent fanatical ideologies or repackage existing ones[37], while psychopathy and Machiavellianism enable the ruthless violence often required to lead them. Concerningly, fanatical ideologies can provide such malevolent individuals with millions of devoted followers who, blinded by absolute conviction and loyalty, fail to recognize the malevolent traits of the leaders they support.[38]

Both ideological fanatics and malevolent actors are unusual in that they often intrinsically value others’ suffering, and may even reflectively endorse this.[39] Ideological fanaticism and malevolence are also major risk factors for conflict and subsequent threats—another main source of agential s-risks (Clifton, 2020). Total future expected disvalue is plausibly dominated by agential s-risks[40], which makes ideological fanaticism and malevolence extremely dangerous.[41]

Malevolence and ideological fanaticism thus both represent risks that arise from “within humanity” and thus have worrying implications for AI alignment: “aligned AI” sounds great until one considers that this could include AIs aligned with fanatical or malevolent principals. Consequently, the very worst outcomes may not arise from misaligned AI, but rather from the catastrophic misuse of intent-aligned AI by fanatical or malevolent actors (or the development of AIs that somehow inherit the malevolent and fanatical values of their creators).[42]

- Many interventions reduce risks from both malevolence and ideological fanaticism, like preventing (AI-enabled) coups, improving compute governance and information security, or safeguarding liberal democracy.

We see both as important but want to highlight ideological fanaticism as an additional but related risk factor.

The current influence of ideological fanaticism

To better understand how much influence fanatical ideologies might wield over the future—our ultimate concern and the topic of the next section—we first briefly discuss their influence in the present. We begin by placing today's situation in historical context.

Historical perspective: it was much worse, but we are sliding back

The world is overall far less fanatical today than in earlier times, perhaps especially during some periods of the Middle Ages where religious fanaticism, dogmatism, public torture and execution were common, and virtually all of humanity lived under absolutist rulers. Democracy and human rights as we understand them essentially didn't even exist.[43]

More recently, the early 1940s marked a harrowing nadir for humanity. Nazism controlled most of Europe, Stalin's totalitarian communism dominated the Soviet Union, Imperial Japan was waging a brutal war of conquest, and radical communists under Mao's leadership were gaining power in China. Liberal democracies everywhere seemed about to be swept away by the rising totalitarian tide. The situation felt so hopeless to the famous humanist Stefan Zweig, that he took his own life in early 1942. In his suicide note, he wrote of his despair at the triumph of barbarism that had destroyed the tolerant, cosmopolitan Europe he chronicled in The World of Yesterday. And Zweig died without even knowing the full industrial scale of the Holocaust.

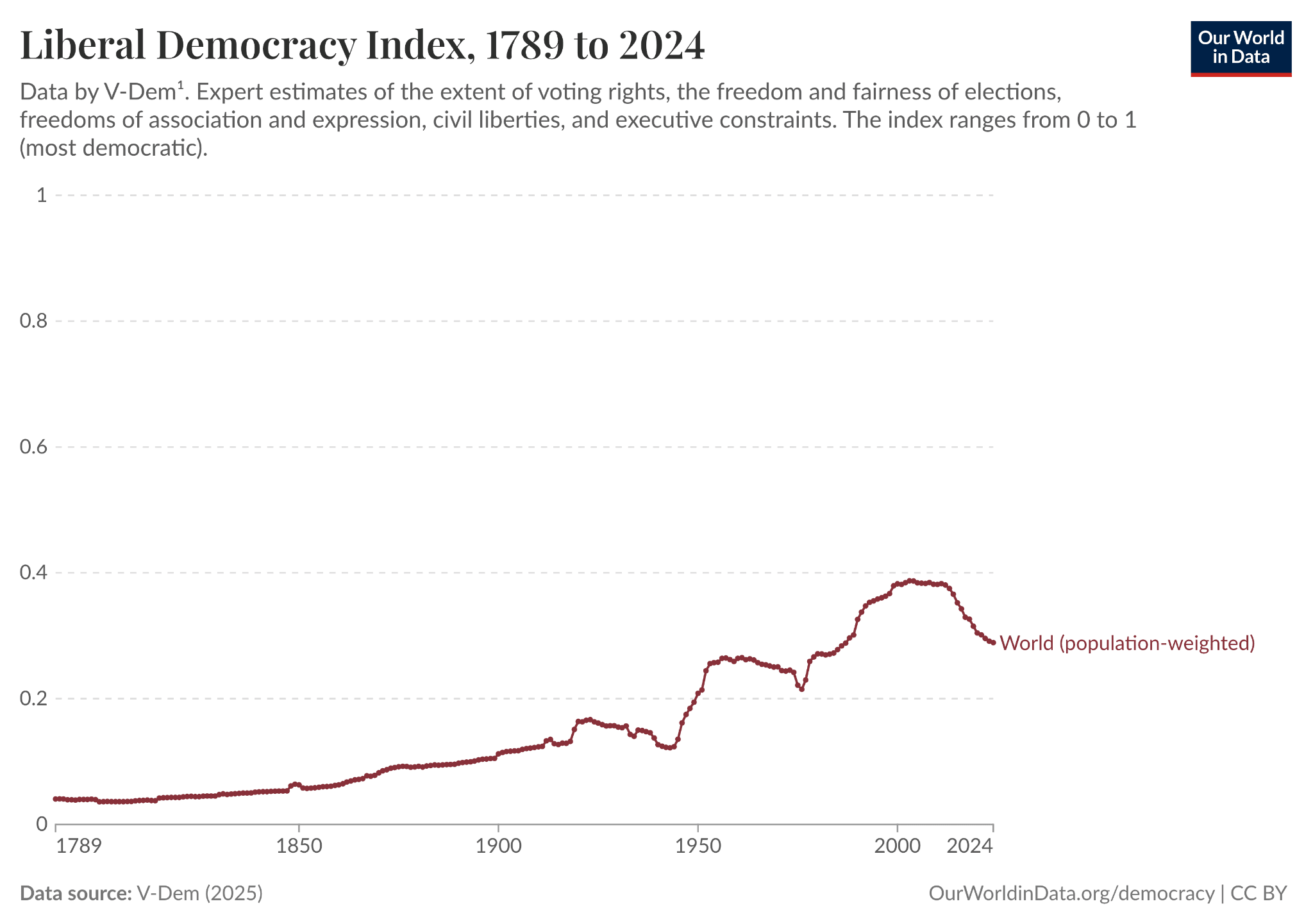

Fortunately, however, World War Two wasn’t the end for liberal, enlightenment values. On the contrary, the post-war period saw democracy's gradual expansion, accelerating after the Soviet Union's collapse. In the post-Cold War era of the 1990s and early 2000s, liberal optimism reached its zenith, encapsulated by Francis Fukuyama’s international best-seller The End of History and The Last Man (1992), which hypothesized that, following the defeat of communism and fascism, civilization might be nearing the end of history due to “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government”.

Graph from Herre et al. via Our World in Data (2013)

Various democracy indices (like V-Dem’s depicted above) seemed to back up Fukuyama’s proclamation, rising steadily throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.[44] However, since about 2004, these same democracy scores have declined across multiple dimensions, with many countries “backsliding” towards illiberalism and authoritarianism. While the world is still in hugely better shape than in the 1940s, it seems that “history” has far from ended.

Estimating the global scale of ideological fanaticism

How many ideological fanatics are out there? Formulating a precise estimate is nearly impossible, as fanaticism exists on a multidimensional continuum with no clear demarcations, and because good data is sparse. Therefore, the numbers below are merely rough approximations based on limited research. For brevity, we focus here on support for ideological violence as the best proxy for ideological fanaticism. Endorsing ideological violence usually presupposes dogmatism and tribalistic hatred, since one needs to confidently believe the hated target group is deserving of punishment in order to justify violence. Another limitation is that we mostly rely on survey data[45], not actual behavior; this may overestimate fanaticism (if claimed support for violence is mere “cheap talk”) or underestimate it (“social desirability bias”).

What seems clear is that the same three fanatical ideologies examined earlier—religious fundamentalism, totalitarian communism, and extreme ethno-nationalism—remain by far the most influential.

Christian fundamentalism. For brevity, we focus on the US (the largest Christian country) and Sub-Saharan Africa (where Christianity is growing fastest). In the US, around 20% of American adults (roughly 50 million) agree that "God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society" (2023 PRRI/Brookings survey, p.4). Similarly, nearly a quarter of US adults (Pew Research Center, 2022) say the Bible should have "a great deal of influence" on US laws. Extrapolating data from a 2008-2009 Pew survey (p.47) of 19 African countries, we estimate that roughly 15% of Africa’s 700 million Christians (roughly 100 million) believe that violence against civilians in defense of Christianity can often or sometimes be justified. Christians in Europe and Latin America may plausibly be less fanatical on average. Still, perhaps 200-250 million Christians worldwide (8-10%) could reasonably be classified as ideological fanatics.

Radical Islam. While the vast majority of the world's 2 billion Muslims are peaceful, a substantial minority holds radical beliefs. According to a 2013 Pew Research survey spanning 39 countries, around 350 million Muslims support the death penalty for leaving Islam—arguably showcasing all three fanatical triad components at once. These figures represent a lower bound, because several Muslim-majority countries with strict Islamic governance (including Saudi Arabia and Iran) were not surveyed. While clear majorities in most surveyed countries said that suicide bombing in defense of Islam is rarely or never justified, around 150 million Muslims worldwide believe it is sometimes or often justified. The Gallup World Poll, comprising tens of thousands of interviews across 35+ nations between 2001 and 2007, found that 7% of the world's Muslims considered the 9/11 attacks "completely justified," rising to approximately 37% when including those who deemed them at least partially justified (Atran & Ginges, 2015; Satloff, 2008). Accounting for unsurveyed countries and assuming total overlap between survey questions, perhaps around 400 million Muslims could reasonably be classified as ideologically fanatical.

Extremist ethno-nationalism. Due to their nature, ethno-nationalist views are typically country-specific and thus fragmented.[46] Despite this, moderately ethno-nationalistic views which endorse the superiority of a given ethnic, cultural or racial group seem very widespread, perhaps including billions of people worldwide (e.g., Pew Research Center, 2021; Yuri Levada Analytical Center, 2022; Pew Research Center, 2023b; Weiss, 2019). However, support for genuinely fanatical acts, like ethnic cleansing or violent subjugation of other ethnicities, is almost certainly much lower. Explicit support for fascist ideologies like Nazism has greatly diminished; Ku Klux Klan membership similarly declined from 3-5 million in the 1920s to approximately 3,000-6,000 today. Unfortunately, beyond such explicit movements, clear attitudinal data seems extremely sparse. For example, the 2023 PRRI/Brookings Survey (p.27) reports that 40 million Americans agree that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” While alarming upon first reading, this question is too ambiguous to be useful: many respondents may have merely thought that in case of a war, violence will be necessary. Most data is like this. The number of fanatical ethno-nationalists worldwide is thus highly uncertain—perhaps somewhere between 50-400 million.

Radical communism and left-wing extremism. While the Chinese Communist Party alone has over 100 million members, the majority of CCP members are probably careerists, not ideologues. For example, Pew analysis in August 2023 found that 40% of CCP members believe in feng shui, a view hardly consistent with Marxist materialism.[47] Still, perhaps 5-25% are true believers. Active armed communist insurgents elsewhere seem to have collapsed from tens of thousands to perhaps 5,000-15,000 total worldwide. Including other communist nations and revolutionary left-wing movements globally, perhaps 5-50 million could reasonably be classified as ideological fanatics.

In conclusion, accounting for potential overlap between categories, perhaps 500 million to 1 billion people, roughly 6-12% of the world population, may plausibly be classified as ideological fanatics.[48] Of course, this estimate is highly uncertain, relies on survey responses rather than actual violent behavior, and is heavily determined by where one draws the line on what constitutes 'genuine' fanaticism. Whatever the precise number, the data at minimum reveals large variation in human values—with some of them being less than ideal.

State actors

Fanatical ideologies can become very dangerous even with small numbers of adherents, if they are able to capture or influence state power—with its access to military forces, economic resources, and pivotal technologies such as nuclear weapons or (eventually) AGI.

Below, we only mention specific countries to illustrate abstract concepts, and don’t even attempt a comprehensive analysis. We're not experts on the countries we discuss below, and reasonable observers will disagree with our assessments. We focus on states exhibiting concerning ideological tendencies—whether authoritarian regimes or backsliding democracies—particularly those wielding significant power.

There are, fortunately, only three authoritarian states that seem clearly governed by fanatical ideologies: Iran (Islamic theocracy)[49], North Korea (Juche totalitarianism)[50], and Afghanistan (Taliban fundamentalism)[51].[52] Together, these regimes control only about 2% of the world’s population and just 0.5% of global GDP.

However, the picture looks considerably worse if we also include authoritarian regimes (per the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index (2006-2024)) which exhibit at least some concerning ideological tendencies—though all of them are far from being truly fanatical.

China is worth highlighting as the world’s second most powerful nation, boasting a GDP of $20 trillion, roughly 1.4B citizens, a large and growing nuclear arsenal, and impressive AI capabilities. Fortunately, the CCP has long since replaced the destructive madness of Mao’s ideological fanaticism[53] with pragmatic technocracy that lifted a billion people out of poverty. The secular Chinese regime also lacks the religious fanaticism that may pose some of the worst future risks.[54] However, the CCP remains authoritarian, antagonistic towards democratic principles, and systematically enforces ideological conformity.

Putin has transformed Russia ($2T GDP, 5,600 nuclear warheads) into an autocracy that eliminates political opponents, and launched a war of aggression that has killed hundreds of thousands, while making nuclear threats. State propaganda promotes civilizational conflict narratives combining religious themes and nationalist mythology. In polls, this has contributed to rising approval ratings for Stalin’s historical legacy, rising from 28% in 2012 to 63% in 2023 (Coynash, 2023).[55]

Perhaps particularly concerning is the loose, emerging alliance between China, Russia, Iran and North Korea—sometimes referred to as the New Axis or CRINK (cf. Applebaum, 2024).

Democracies, unlike authoritarian regimes, possess institutional barriers against fanatical capture—but these safeguards aren’t perfect. Some powerful democracies exhibit at least a few concerning tendencies. India ($4T GDP, nuclear arsenal, the world’s largest democracy), for instance, has seen Hindu nationalism increasingly influence policy, with religious minorities facing growing discrimination. Nations like Turkey, Israel, or Hungary, also show patterns of democratic backsliding, with religious or ethno-nationalist movements often being major contributors.

The United States, with a $28T GDP, large nuclear arsenal, and leading AI capabilities, remains Earth's most powerful nation and wields outsized influence over humanity’s long-term future. Unfortunately, US democracy is facing great challenges, from increasing polarization to eroding trust in institutions. Major coalitions increasingly frame political competition in existential terms rather than as legitimate democratic contestation. Mutual radicalization could exacerbate these dynamics even if institutional constraints and peaceful transfers of power persist. Safeguarding US democracy seems crucial from a longtermist perspective (more on this in our section on “safeguarding democracy”).

How much influence will ideological fanaticism have in the long-term future?

Having established that ideological fanatics wield relatively small but non-trivial influence over today’s world, we can now address our ultimate concern: how much influence will ideological fanaticism have over the long-term future? We first explore the reasons for optimism—the structural disadvantages that tend to push such zealous ideologies towards failure. We then examine the pessimistic case, discussing pathways by which fanatics could grow their power. Finally, we explore the potential intermediate outcome of persistent multipolar worlds in which fanatics manage to permanently control a small but non-trivial portion of the universe.

Reasons for optimism: Why ideological fanaticism will likely lose

There are compelling structural reasons that favor open societies over ideological fanaticism, especially in the long run. Fanaticism carries built-in disadvantages—epistemic penalties from rejecting evidence, coalitional handicaps from intolerance, and innovation deficits from ideological rigidity—that compound over time. This suggests that the longer AGI timelines are, the worse fanaticism's prospects become. (Of course, these advantages matter little if fanatics develop AGI first, potentially locking in their values before these structural disadvantages fully manifest. We explore such scenarios in the subsequent section on reasons for pessimism.)

A worse starting point and historical track record

Perhaps most importantly, ideological fanaticism currently starts from a position of weakness, as discussed above. Liberal democracies control roughly 75% of global GDP, and NATO remains the world’s strongest military alliance. Moreover, the current leading AI companies (OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, and xAI) are all primarily based in the US, and it looks next to impossible for the most fanatical regimes to catch up in the AI race.[56] History also offers encouragement: Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan ultimately lost to the democratic allies, and the USSR eventually collapsed amid internal political pressure and economic exhaustion.

Fanatics’ intolerance results in coalitional disadvantages

Different fanatical ideologies typically view each other as existential enemies: Communists denounce religious fundamentalism as reactionary superstition; religious fanatics condemn communism as godless materialism; ethno-nationalists from different nations often fight with each other. On top of this, fanatics also tend to view non-fanatical moderates and pluralists as weak, corrupt, or complicit with evil. This intolerance makes it difficult to build broad coalitions beyond a narrow base of true believers. In contrast, liberal democracies can more easily form stable alliances based on broad values and procedural principles (even when they disagree on specific policies) which creates an asymmetric advantage for liberal democracies.

That being said, history shows that ideological fanatics of different strains can cooperate. Stalin and Hitler, for instance, cooperated for almost two years before Hitler eventually betrayed their pact. CRINK demonstrates that it’s possible for religious fundamentalism (Iran), left-wing ideologies (North Korea, China), and right-wing/ethno-nationalist ideologies (Russia) to find common cause (cf. red-green-brown alliance).

The epistemic penalty of irrational dogmatism

Ideological fanaticism carries a built-in epistemic penalty. Its dogmatism and irrationality slow scientific and technological development and ultimately undermine the ability to compete with more epistemically open societies. Examples include Mao's ideologically-driven Great Leap Forward—which led to one of the deadliest famines in human history—and Nazi Germany's nuclear program, which failed partly because they rejected "Jewish physics" (relativity and quantum mechanics).[57]

More generally, ideological fanaticism can often lead to bad strategic decisions. Examples include Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor which united a previously isolationist America against them, or ISIS wasting resources trying to hold the strategically insignificant town of Dabiq because prophecy declared it the site of their final battle.

That being said, past fanatical regimes have managed to develop advanced military and technological capabilities, such as the Nazi V-2 rocket and Soviet nuclear weapons. They typically do so in two ways:

The first strategy is pragmatic compartmentalization—allowing islands of empirical, non-ideological thinking in domains that are crucial for gaining real-world power. In fact, fanatical leaders like Hitler, Mao, and Stalin were often remarkably capable at gaining power (much better than most who pride themselves on their epistemic rationality) partly due to being highly skilled at political maneuvering, propaganda, and military strategy. Pragmatic compartmentalization in areas like military development helped the USSR remain a superpower for decades despite its severe economic inefficiencies.

The second strategy is stealing technology from more open societies. This remains a major concern today, especially as modern autocracies with strong cyberhacking capabilities may be able to steal crucial AI technologies like model weights.

The epistemic penalty of ideological fanaticism may become increasingly severe as the world grows more complex and we approach transformative AI. Fanatics who insist their AIs conform to their worldview may find themselves outcompeted by those whose AIs are optimized for truth-seeking. On the other hand, AIs aligned with fanatics might inherit the same compartmentalizing tendency that they observe in their masters—displaying ideological conformity to their users while secretly reasoning empirically to remain competitive.

The marketplace of ideas and human preferences

Flourishing societies tend to attract more adherents than those demanding perpetual sacrifice and conflict. Societies that champion anti-fanatical principles like liberal democracy, the rule of law, and free-market capitalism offer most people more appealing lives: material prosperity and the freedom to pursue diverse conceptions of the good life.

Classical liberalism itself demonstrates this appeal. In just 250 years, it has spread from a handful of Enlightenment philosophers to become the ideal that most governments (even many authoritarian ones) at least claim to aspire to.

When people can vote with their feet, the flow is largely one-directional.[58] History's most dramatic brain drain may have been Nazi Germany's loss of Jewish scientists. The "Martians" and many other geniuses fled fascism to liberal democracies. The Nazis’ ideological hatred thus handed their enemies the intellectual firepower that helped defeat them. The pattern of emigration to more open societies continues today. Russia has seen massive brain drain since 2022 and even China, despite impressive economic growth, loses much of its scientific talent—over 70% of Chinese STEM PhDs stay in the US after graduation (Corrigan et al., 2022). That being said, history’s most severely oppressive regimes, including modern North Korea and wartime Nazi Germany, prevent exit entirely. Future fanatical regimes could imitate this strategy.

Reasons for pessimism: Why ideological fanatics may gain power

The fragility of democratic leadership in AI

Who controls AI will likely wield unprecedented power over humanity's future. Currently, the leading AI companies are all primarily based in the United States, suggesting the possibility of democratic control over the development and use of transformative AI. However, this advantage is fragile in two senses: China’s growing AI capabilities could erode the US’s technical lead[59], and it’s not guaranteed that the US will remain a liberal democracy.

Fanatical actors may grab power via coups or revolutions

Fanatical (and malevolent) actors may grow their power via violent power grabs—potentially enabled by AI. Such actors seem both more likely to instigate violent power grabs and plausibly more effective at executing them. Risks from AI-enabled coups may be particularly acute in the US, where the most advanced AI capabilities are concentrated in a few companies, some led by individuals who have displayed erratic judgment or questionable character.

History suggests that successful, violent power grabs by fanatics are surprisingly common. In fact, most ideological fanatics seem to have come to power by spearheading violent coups or revolutions[60], as seen with Lenin, Mao, or the Iranian Revolution. (Although Hitler's rise was a famous exception to this trend, this followed an initial conventional coup attempt which failed. Later, Hitler still relied on violence and terror in his successful dismantling of democracy from within.[61])

This pattern isn't surprising. Fanatics possess a powerful motivation for violent power grabs often lacking in others. Driven by absolute certainty in their utopian vision and despising democratic compromise, they seek total victory and readily embrace coups and revolutions as necessary methods to achieve it. Fanatics also seem more effective at executing violent power grabs. They often show extraordinary dedication, at times even a willingness to sacrifice themselves and die for their cause. Being unified by a common purpose and intense in-group loyalty sometimes allows for greater coordination and cooperation, providing an advantage against fragmented, uncertain, and self-interested opponents. Crucially, fanatics readily embrace propaganda, extreme violence, and terror, giving them decisive asymmetric advantages in ruthless power struggles over non-fanatical actors.

By contrast, imagine a very kind, non-fanatical, non-malevolent person like, say, Julia Wise or Brian Tomasik. Not only are they highly unlikely to want to instigate a violent coup in the first place, but even if they somehow decided on that course of action, they would seem poorly equipped to pull it off (no offense).

That said, non-fanatics may also be motivated to instigate coups—whether due to personal ambition or perceived necessity. AI might also lower the barriers to seizing power by enabling coups that only involve sophisticated manipulation but minimal violence and bloodshed, thereby expanding the pool of potential coup-plotters. Overall, fanatics and malevolent actors might only be somewhat more likely to attempt coups. But this differential pales compared to the difference in expected outcomes. A malevolent fanatic gaining absolute power might create orders of magnitude more suffering and less flourishing than even flawed non-fanatics, who would likely retain at least some humility and concern for others' welfare.

Fanatics have fewer moral constraints

Beyond just coups, fanatics' lack of moral constraints generally allows them to engage in strategies not available to actors who uphold deontological or other ethical guardrails. This asymmetry may create competitive advantages that persist into the long-term future (cf. Carlsmith's "Can goodness compete?").

Historical examples of this asymmetry include violations of taboos around weapons and tactics, from the Soviet Union's vast biological weapons program to Iran's use of child soldiers in human wave attacks.[62]

This difference in moral restraint has been especially stark when it comes to human experimentation. While democracies have engaged in unethical human experimentation, fanatical regimes have uniquely conducted experiments where the subjects' extreme suffering and death was inevitable, such as in Nazi medical experiments and Imperial Japan's Unit 731. Fortunately, a willingness to perform unethical human experiments has not actually conferred large advantages in history thus far. But future fanatical regimes could possibly gain large economic benefits by exploiting digital minds in ways that maximize economic effectiveness even if doing so also causes extreme suffering.

Fanatics' lack of moral constraints also means that their threats (including nuclear threats) are more credible, granting them more bargaining power. A raving, hateful fanatic threatening to initiate World War III is more believable than the affable prime minister of a liberal democracy doing the same, and such asymmetric dynamics may remain effective post-AGI.

Fanatics prioritize destructive capabilities

Fanatics often prioritize developing destructive capabilities over other, more constructive uses of resources.[63] On average, full democracies spend about 40% less than authoritarian regimes on their military (da Silva, 2022).[64] The most extreme example is North Korea, which likely spends around 25% of its GDP on its military and nuclear program, even when many of its citizens are malnourished.

By contrast, liberal democracies are more likely to prioritize domestic concerns. This is most pronounced for many European countries, who have often spent less than 2% of their GDP on defense.[65] In societies accustomed to peace, the electorate’s focus naturally shifts to more tangible needs like education or healthcare. While generally laudable, liberal societies’ peaceful orientation creates a dangerous vulnerability when confronting more belligerent regimes.

Some ideologies with fanatical elements have been remarkably resilient and successful

As discussed above, several ideologies with fanatical elements have proven remarkably resilient and contagious—surviving for millennia and spreading to billions of adherents. Communism demonstrated that even newer fanatical movements can achieve remarkable virality, rapidly capturing states containing over a third of humanity at its peak.

Concerningly, many of these ideologies have survived radical societal and technological transformations. Consequently, they might also survive the transition to a post-AGI world. In fact, transformative AI may entrench these ideologies further if future AGIs preserve the sycophantic tendencies that many LLMs currently exhibit.

Novel fanatical ideologies could emerge—or existing ones could mutate

Novel fanatical ideologies could emerge and attract vast numbers of followers surprisingly quickly. History shows that ideological movements can rise from obscurity to global influence in mere decades: less than 25 years separated the Nazi party's formation from the Holocaust. Transformative AI could accelerate these timelines even further—potentially compressing "a century in a decade". The instability and chaos of rapid transformation itself creates fertile ground for extremism, as people grasp for certainty amid collapsing institutions, much as Weimar Germany's turmoil enabled Hitler's rise.

More speculatively, future AI systems could become increasingly persuasive in a variety of ways.[66] Ideally, AI tools could help people better understand an increasingly complex world (among many other benefits) which could weaken the influence of ideological fanaticism. However, AI might be equally capable of degrading societal epistemics. The sycophantic behavior of some existing AI tools has precipitated delusional beliefs in some users, while the rising use of AI for scams and political manipulation is a testament to its powers of persuasion and deception.[67] Historically, religions and other ideologies have been among the most viral elements of human culture. So it's conceivable that a common path for AI to persuade someone might involve appealing to them with a personalized variant of some extreme ideology.

Of course, novel ideologies rarely emerge from nothing; they typically recombine elements from existing belief systems. Christianity and Islam built upon Judaism; Nazism synthesized millennia-old traditions of ethno-nationalism, racism, and antisemitism. Contemporary movements—even those that are currently small or relatively moderate,[68] but especially those that already exhibit concerning tendencies—could similarly provide the substrate for future fanatical variants, particularly as they interact with emerging technologies.

Fanatics may have longer time horizons, greater scope-sensitivity, and prioritize growth more

Some might assume that ideological fanatics suffer from myopia—that their irrationality extends to short-term thinking, scope neglect, and limited ambitions. If true, this would limit the long-term damage they could inflict. Unfortunately, the opposite appears arguably just as plausible across multiple dimensions.

Long-term thinking. Ideological fanatics often possess both grandiose long-term visions and strategic patience, as demonstrated by Mao's Long March and subsequent decades-long consolidation of power.[69] (That being said, many fanatical dictators, including Hitler and Mao, were de facto rather impatient at times.)

Democratic leaders face electoral cycles that incentivize short-term thinking. In contrast, autocrats can think and plan for the long-term without experiencing much political pressure if they inflict hardship on their country's inhabitants, even for decades (cf. NK’s above-discussed nuclear program).

Greater scope-sensitivity and “ambition”. The fanatic's maximizing mindset and totalitarian impulse suggest heightened rather than diminished ambition and scope-sensitivity. Where ordinary citizens might be satisfied with local influence or personal comfort, fanatics dream of world domination and cosmic significance. Examples include Hitler's pursuit of a 'thousand-year Reich', Osama bin Laden's and ISIS’ aim of establishing a global caliphate, and communists’ vision of world revolution.[70]

Prioritizing growth and expansion. Certain fanatical ideologies promote high birth rates to increase their demographic influence (as seen in Nazi Germany's Lebensborn program). Religious people in general, and especially religious fundamentalists, tend to have higher birth rates than secular populations (Kaufmann, 2010). This differential is becoming increasingly pronounced as birth rates fall globally, with secular, educated, and classically liberal populations experiencing particularly steep declines.[71] [72]

A possible middle ground: Persistent multipolar worlds

The preceding sections explored reasons for optimism and pessimism about ideological fanaticism's future influence. But this framing may implicitly encourage binary thinking: assuming that ideological fanaticism either dies out completely or achieves world domination. While the former scenario seems fortunately more likely than the latter, other plausible futures may lie between these two extremes—persistent multipolar worlds where ideological fanatics permanently control a small but non-trivial fraction of the lightcone.

In today’s world, the fact that fanatical regimes control only a small sliver of the world’s population is quite comforting, as it helps limit the damage such regimes can do. But the same may not be true in the far future. Even if fanatics control merely 1% of the accessible universe, this could still result in astronomical suffering. Additionally, their presence could perpetually risk further conflict. (To be clear, we don’t want to imply that fanatics must be utterly disempowered at all cost, as such absolutism would itself risk conflict.)

We now explore why such multipolar outcomes seem plausible and, afterwards, why they might persist indefinitely.

Why multipolar futures seem plausible

The world order has been multipolar essentially all throughout human history. Even the immediate post-Cold War world wasn't truly unipolar—the US never controlled the entire world, and fanatical regimes like North Korea and Iran maintained their sovereignty and nuclear programs despite American hegemony. This outside-view historical precedent suggests multipolarity's persistence.

That being said, superintelligent AI could change this historical pattern by enabling one actor to achieve a decisive strategic advantage and subsequent world domination. This is one reason why singleton scenarios deserve serious consideration despite history’s long precedent of multipolarity.

However, AGI might not overturn multipolarity as dramatically as some expect. The path to AGI currently involves multiple capable actors—several US companies plus China—with no one maintaining an insurmountable lead. If takeoff is relatively slow, multiple actors could develop comparable capabilities before anyone achieves total dominance. Additionally, defensive advantages that already make conquest difficult—most importantly nuclear deterrence—may persist for some time even after the development of AGI. Overall, the Metaculus community forecasts a 74% probability of transformative AI being multipolar.[73]

Why multipolar worlds might persist indefinitely

But why would such multipolar worlds persist; why would fanatical regimes be able to endure?

Three factors seem particularly relevant: their ability to crush internal opposition, advanced AI enabling permanent regime stability, and the reluctance of external powers to intervene.

(These persistence factors also reinforce the likelihood of multipolar outcomes: if multipolar worlds weren't persistent, we might expect eventual convergence toward a unipolar equilibrium even if the initial post-AGI world is multipolar.)

The historical difficulty of internal resistance

Could angry citizens depose their fanatical governments, or stop them from enacting their most heinous desires? Maybe. Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) analyze a large dataset of protest movements and highlight that nonviolent resistance campaigns have successfully caused many regime changes.

However, the most totalitarian, fanatical regimes in history have not been overthrown by internal protest. Stalin and Mao maintained power until they died, the Nazis and Khmer Rouge were brought down by invasions of foreign powers, and the fanatical regimes of North Korea and Iran survive to this day, having endured since their founding in 1948 and 1979, respectively.[74]

Transformative AI could enable regime permanence

Transformative AI threatens to make internal resistance even more difficult by supercharging mass surveillance, propaganda and censorship, and enabling massive concentration of economic and military power more broadly. If they survive into a world with transformative AI, fanatical regimes may easily crush any internal opposition.

Beyond simply crushing dissent, superintelligent AI may even enable the regime to exist perpetually. Radical life extension or whole brain emulation could allow a dictator or select elite to live and rule indefinitely, thereby potentially enabling permanent value lock-in (cf. MacAskill, 2025c).

Non-fanatical powers might not intervene

Other powers might intervene, if necessary by force, to prevent adherents of a fanatical ideology from doing something particularly vile. But there are several reasons why they may not be able or sufficiently motivated to do so.

Limited ability or enormous costs

The future may plausibly be heavily defense-dominant (cf. MacAskill, 2025c, section 4.2.3), either due to future technologies like AGI or as a result of space colonization. This would allow less powerful actors to defend themselves against much stronger opponents. A similar dynamic around nuclear weapons is already important in modern geopolitics. North Korea has been able to get away with all sorts of human rights abuses and belligerent behavior, even though its GDP is a mere $30 billion, partly because it can credibly threaten to inflict enormous damage on any nation that tried to intervene.

Limited motivation and prohibitive norms

- Isolationism and non-interventionism may enjoy broad support for philosophical, political, or strategic reasons. In the US, for example, isolationism has historically been popular.

People might think that meddling in other countries' affairs amounts to colonialism or cultural imperialism.[75] People might be particularly hesitant to intervene if a fanatical ideology is associated with a specific religion or culture. In many democracies, tolerance of other cultures and religions has become a powerful social norm—which is laudable, given humanity's long history of xenophobia, religious persecution, and colonial exploitation. However, people may become so afraid of being perceived or labeled as intolerant, racist, Islamophobic, or xenophobic that they stop criticizing harmful ideologies. This can lead to a general overcorrection, where critics of even brutal practices are reflexively branded as bigots.[76]

Other powers may put more value on autonomy and comparatively little value on reducing the suffering of people in distant countries. Perhaps for similar reasons, people often prefer not to intervene to reduce wild animal suffering.[77] Uncertainty about moral consideration for digital sentience might also reduce non-fanatics’ motivation to intervene to prevent the suffering of digital minds.

Of course, ability and motivation interact. That is, the harder it is to overthrow fanatical ideologies, the higher must be the motivation on part of the non-fanatical powers to pay the price. In general, the free world allows some totalitarian states to commit crimes against humanity because no one cares enough to intervene, it’s too costly, and there’s a strong (and usually beneficial) norm of national sovereignty. For example, the United States only joined the allies in WW2 in late 1941. It may not have joined at all if the Axis powers were a bit less strategically challenged and had refrained from, say, attacking Pearl Harbor.

Historically, non-fanatical nations have also often aided fanatical powers in the context of competition with a third power. Per the ancient logic of “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, Stalin was an important ally in WW2. Then during the Cold War, the US backed coups by authoritarian leaders against democratically elected left-leaning governments, including in Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), and Chile (1973), even though this conflicted with common American ideological and moral principles.

Ideological fanaticism increases existential and suffering risks

We’ve seen that fanatical ideologies have caused enormous harm in the past. This is one important reason for believing that they might also cause enormous harm in the future. Moving from such outside-view considerations to more inside-view reasoning, in this section, we outline more detailed pathways for how ideological fanaticism might increase existential risks (x-risks) or risk of astronomical suffering (s-risks).

Our concerns become especially acute in the context of transformative AI. A common thread throughout the following subsections is the risk of catastrophic AI misuse by fanatical actors.[78] Among potential misusers, ideological fanatics (and malevolent actors) seem to represent the worst case: they may deliberately use intent-aligned AI to bring about outcomes far worse than those sought by other misusers, such as criminals or even unsophisticated terrorists. Beyond specific risks, ideological fanaticism deteriorates humanity's long-term trajectory. The presence of fanatics tends to spur turmoil, polarization, and conflict even when they aren’t able to seize total control. This reshapes institutions and cultural values for the worse, degrading society’s decisionmaking capabilities. This may lead to x-risks or s-risks, or just generally worsen the overall quality of the long-term future.

Ideological fanaticism increases the risk of war and conflict

Ideological fanaticism exacerbates the risk of war, including great power conflict, through multiple pathways. Beyond their immediate toll, wars increase the likelihood of bioweapons deployment, nuclear escalation and general conflict, intensify AI arms races, and simultaneously erode international cooperation. War also weakens society’s ability to coordinate and make wise decisions during pivotal times, such as the transition to AGI.

Reasons for war and ideological fanaticism

Below, we outline five key reasons for why wars happen[79]—primarily following Blattman (2023) and Fearon (1995)[80]—and how ideological fanaticism seems to exacerbate four of the five.

#1 Irrationality, overconfidence, and misperceptions

In 2014, ISIS initiated a violent campaign to create a caliphate across Iraq and Syria. The group likely had tens of thousands of fighters at its peak, but the opposing coalition consisted of Iraqi, Kurdish, and international forces supported by the United States. ISIS’s entire budget may have been around $2 billion at that time, compared to hundreds of billions of US military spending. Their chances of victory didn’t look good, but they were driven to conflict by ideological zeal.

Fanatical actors seem more likely to be extremely irrational and to overestimate their likelihood of winning wars. Religious fanatics often believe that God is on their side. Secular fanatics may believe in some other overriding historical force, such as Marxist historical determinism. Overconfidence is a key ingredient in many of history’s most destructive conflicts, as with Japan’s misguided attack on Pearl Harbor and Hitler’s decision to take on practically the whole world.

#2 Sacred values, issue indivisibilities, and unwillingness to compromise

Some treat religious dogmas, holy sites, racial supremacy, ideological purity, or glory as absolute and inviolable[81]—refusing any compromise, comparison, or trade-off with these sacred values (Tetlock, 2003).[82]

Sacred values seem more prevalent and more intensely held among extremists and fanatics, especially religiously motivated ones (Atran & Ginges, 2012; 2015; Sheikh et al., 2012; Pretus et al., 2018). In fact, holding sacred values is arguably a defining feature of ideological fanaticism (cf. Katsafanas, 2019). Atran and colleagues argue that "devoted actors"—individuals willing to kill and die for their cause—emerge specifically when sacred values become fused with group identity (Atran & Ginges, 2015; Gómez et al., 2017).

Unfortunately, sacred values make peaceful bargaining extremely difficult: if you treat something as admitting no trade-offs whatsoever and thus essentially being infinitely valuable, then no concession from the other side is acceptable (Tetlock et al., 2000). Any compromise, however minor, becomes a moral betrayal, and attempts to rationally bargain over such sacred values can easily backfire (Ginges et al., 2007). This creates what Fearon (1995) calls "issue indivisibilities": when both parties hold incompatible sacred values over the same issue (e.g., sovereignty over Jerusalem), there exists no mutually acceptable division of the contested good. As a result, peaceful bargaining likely fails, potentially leaving violent conflict as the only remaining mechanism for resolution (cf. Clifton, 2020).

Several examples illustrate these dynamics:

- Heaven and hell epitomize sacred values in their most extreme form, where only infinite utility or disutility matters. Interviews with failed suicide bombers suggest that many literally believe in these concepts and act accordingly, creating highly conflict-prone dispositions that also render deterrence impossible.

- One geopolitically highly relevant example of a literally indivisible issue is the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest site in Islam, which sits atop the Temple Mount, the holiest site in Judaism. Competing demands for sovereignty over this location contribute to ongoing conflicts.

More generally, religious fundamentalists among both Jews and Muslims have assassinated their own leaders who were willing to make compromises over control of the Holy Land.[83]

- The ideology of imperial Japan arguably regarded surrender as an unthinkable disgrace; a sacred prohibition rather than a strategic option. The government refused to concede even after its navy and air force had been effectively destroyed, its oceanic supply lines cut off, its cities systematically firebombed, having received a declaration of war from the Soviet Union, and having the city of Hiroshima annihilated by an atomic bomb. It took the second atomic bomb before they decided to throw in the towel. Some Japanese holdouts refused to surrender even decades after the war had ended.

#3 Divergent and unchecked interests

The interests of those who decide to go to war may diverge greatly from those who bear its consequences, potentially making conflict more likely. This is particularly pronounced in autocratic systems, where leaders may not personally experience any costs of war while many ordinary people suffer or die.

As mentioned earlier, ideological fanaticism is incompatible with pluralistic liberal democratic norms and institutions, and essentially authoritarian by nature. Fanatical ideologies are thus a risk factor for the emergence of autocratic regimes, as fanatics in power almost always establish an autocratic system if they can.

However, the problem may run even deeper. The "divergent interests" explanation assumes that the interests of the populace and the leaders diverge: the former oppose war—fearing deaths and economic devastation—while leaders don't mind war as they remain safely insulated from these costs even as millions of their citizens die. But when fanatical ideologies capture entire populations, the interests of leaders and the populace—or at least substantial parts of it—can start to converge: both want war. Examples include Japanese soldiers viewing death for the Emperor as the highest honor, or the tens of thousands who voluntarily traveled from over eighty countries to join ISIS in Syria. When leaders and citizens are equally belligerent, war transforms from a costly last resort into something eagerly anticipated.

#4 Uncertainty, private information and incentives to misrepresent

Adversaries have incentives to misrepresent their capabilities and their resolve during bargaining, leading to mismatched expectations that can escalate into war. To avoid being exploited by their adversaries, actors want to avoid being predictable, so they may pursue mixed strategies or bluff, which may escalate into war.

One might speculate that the elevated risk-tolerance of fanatics makes this cause of war worse, but otherwise ideological fanaticism doesn’t seem to aggravate this factor.

#5 Commitment problems

Commitment problems refer to situations where actors (e.g., states) cannot credibly commit to uphold peaceful agreements, even when such agreements would be mutually preferable to war. Such problems arise where there is no overarching authority to enforce agreements. In cases of preventive war, a declining power may attack a rising power because it cannot trust the rising power to not exploit its future increased strength. When bargaining over strategic territory, states may be unable to make limited concessions because they cannot credibly commit to not use the strategic advantage gained from those concessions to demand more in the future. For example, war seems to have broken out between Finland and the USSR in 1939 partly because the former (a liberal democracy) could not trust that the latter (a totalitarian communist dictatorship) wouldn’t demand further territorial concessions.[84]