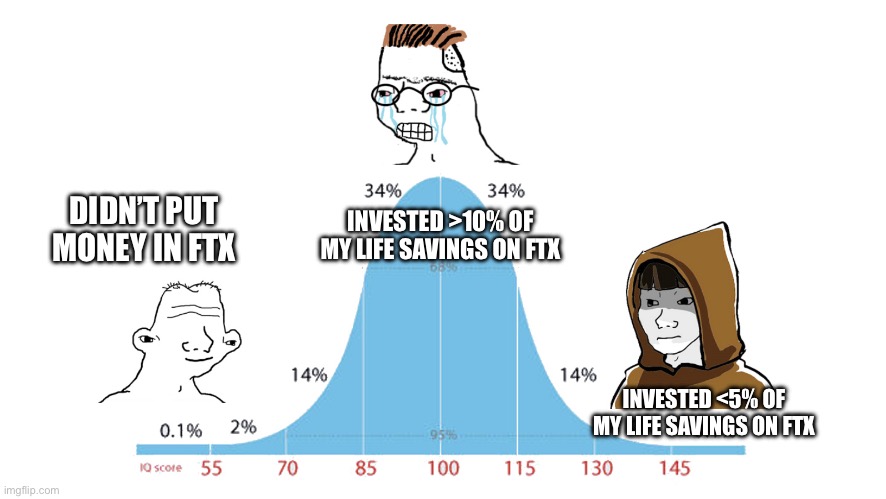

Dylan Matthews has an interesting piece up in Vox, 'How effective altruism let SBF happen'. I feel very conflicted about it, as I think it contains some criticisms that are importantly correct, but then takes it in a direction I think is importantly mistaken. I'll be curious to hear others' thoughts.

Here's what I think is most right about it:

There’s still plenty we don’t know, but based on what we do know, I don’t think the problem was earning to give, or billionaire money, or longtermism per se. But the problem does lie in the culture of effective altruism... it is deeply immature and myopic, in a way that enabled Bankman-Fried and Ellison, and it desperately needs to grow up. That means emulating the kinds of practices that more mature philanthropic institutions and movements have used for centuries, and becoming much more risk-averse.

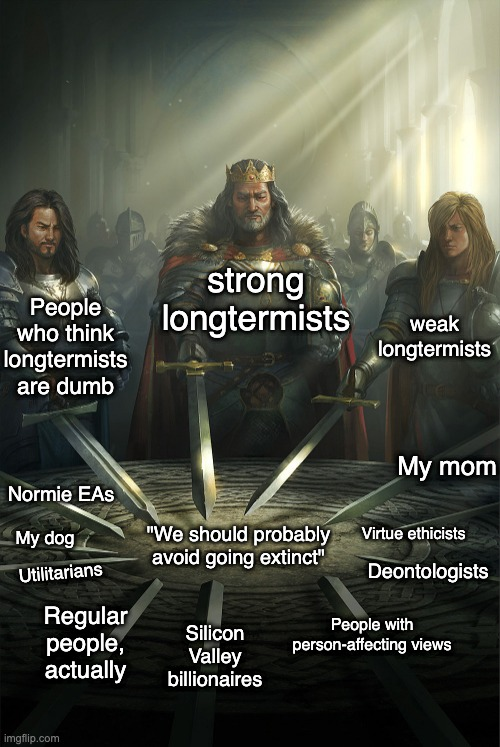

Like many youth-led movements, there's a tendency within EA to be skeptical of established institutions and ways of running things. Such skepticism is healthy in moderation, but taken to extremes can lead to things like FTX's apparent total failure of financial oversight and corporate governance. Installing SBF as a corporate "philosopher-king" turns out not to have been great for FTX, in much the same way that we might predict installing a philosopher-king as absolute dictator would not be great for a country.

I'm obviously very pro-philosophy, and think it offers important practical guidance too, but it's not a substitute for robust institutions. So here is where I feel most conflicted about the article. Because I agree we should be wary of philosopher-kings. But that's mostly just because we should be wary of "kings" (or immature dictators) in general.

So I'm not thrilled with a framing that says (as Matthews goes on to say) that "the problem is the dominance of philosophy", because I don't think philosophy tells you to install philosopher-kings. Instead, I'd say, the problem is immaturity, and lack of respect for established institutional guard-rails for good governance (i.e., bureaucracy). What EA needs to learn, IMO, is this missing respect for "established" procedures, and a culture of consulting with more senior advisers who understand how institutions work (and why).

It's important to get this diagnosis right, since there's no reason to think that replacing 30 y/o philosophers with equally young anticapitalist activists (say) would do any good here. What's needed is people with more institutional experience (which will often mean significantly older people), and a sensible division of labour between philosophy and policy, ideas and implementation.

There are parts of the article that sort of point in this direction, but then it spins away and doesn't quite articulate the problem correctly. Or so it seems to me. But again, curious to hear others' thoughts.

We should distinguish risk aversity, transparency, and bureaucracy. They're obviously related but different concepts. I would argue that transparency is far more important than risk aversity, the more so the less risk averse you are - and unfortunately nontransparency often seems to be correlated with risk-taking. This is sometimes justified on infohazard logic (cf MIRI in general) or some harder-to-pin-down lack of urgency to communicate controversial decisions (cf Wytham Abbey). Increasing transparency necessarily increases bureaucracy, but there are many other ways bureaucracy can increase, so we shouldn't expect it to balloon uncontrollably just because of one upward pressure.

I feel like most core EA organisations would come nowhere near meeting the transparency requirements Givewell place on charities they recommend (though Givewell themselves do impressively well on this score, so it's clearly not impossible for metacharities).