Dylan Matthews has an interesting piece up in Vox, 'How effective altruism let SBF happen'. I feel very conflicted about it, as I think it contains some criticisms that are importantly correct, but then takes it in a direction I think is importantly mistaken. I'll be curious to hear others' thoughts.

Here's what I think is most right about it:

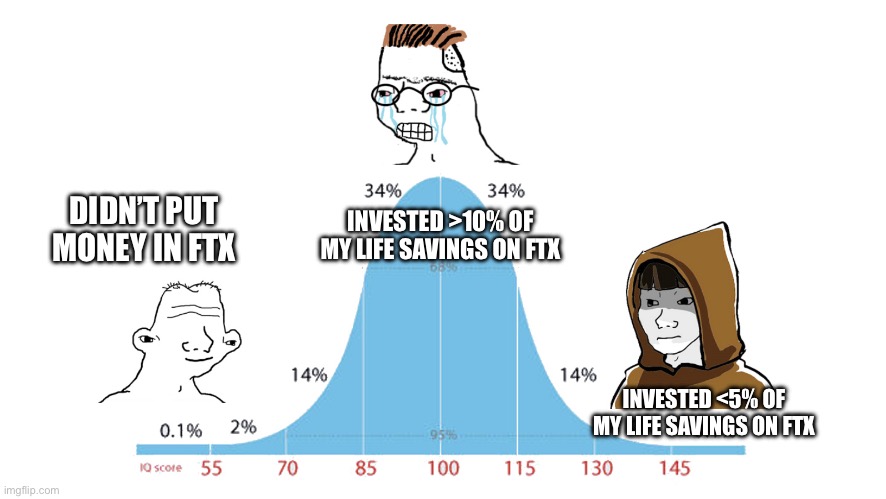

There’s still plenty we don’t know, but based on what we do know, I don’t think the problem was earning to give, or billionaire money, or longtermism per se. But the problem does lie in the culture of effective altruism... it is deeply immature and myopic, in a way that enabled Bankman-Fried and Ellison, and it desperately needs to grow up. That means emulating the kinds of practices that more mature philanthropic institutions and movements have used for centuries, and becoming much more risk-averse.

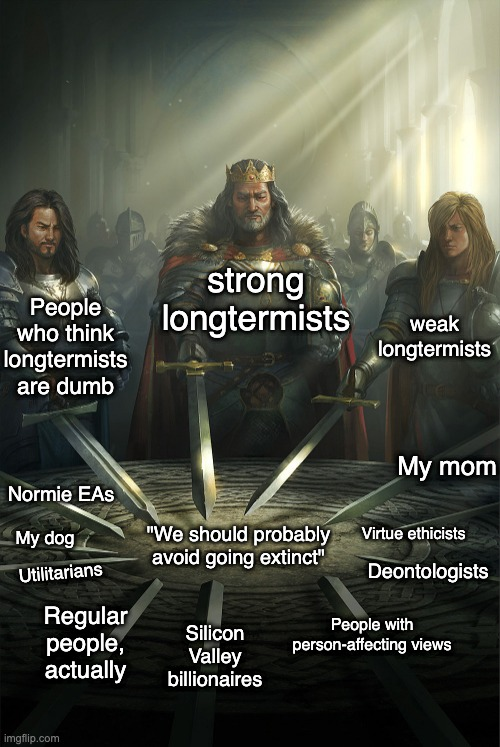

Like many youth-led movements, there's a tendency within EA to be skeptical of established institutions and ways of running things. Such skepticism is healthy in moderation, but taken to extremes can lead to things like FTX's apparent total failure of financial oversight and corporate governance. Installing SBF as a corporate "philosopher-king" turns out not to have been great for FTX, in much the same way that we might predict installing a philosopher-king as absolute dictator would not be great for a country.

I'm obviously very pro-philosophy, and think it offers important practical guidance too, but it's not a substitute for robust institutions. So here is where I feel most conflicted about the article. Because I agree we should be wary of philosopher-kings. But that's mostly just because we should be wary of "kings" (or immature dictators) in general.

So I'm not thrilled with a framing that says (as Matthews goes on to say) that "the problem is the dominance of philosophy", because I don't think philosophy tells you to install philosopher-kings. Instead, I'd say, the problem is immaturity, and lack of respect for established institutional guard-rails for good governance (i.e., bureaucracy). What EA needs to learn, IMO, is this missing respect for "established" procedures, and a culture of consulting with more senior advisers who understand how institutions work (and why).

It's important to get this diagnosis right, since there's no reason to think that replacing 30 y/o philosophers with equally young anticapitalist activists (say) would do any good here. What's needed is people with more institutional experience (which will often mean significantly older people), and a sensible division of labour between philosophy and policy, ideas and implementation.

There are parts of the article that sort of point in this direction, but then it spins away and doesn't quite articulate the problem correctly. Or so it seems to me. But again, curious to hear others' thoughts.

I strongly disagree with this. The key reason is: most of the time, norms that have been exposed to evolutionary selection pressures beat explicit “rational reflection” by individual humans. One of the major mistakes of Enlightenment philosophers was to think it is usually the other way around. These mistakes were plausibly a necessary condition for some of the horrific violence that’s taken place since they started trending.

I often run into philosophy graduates who tell me that relying on intuitive moral judgements about particular cases is “arrogant”. I reply by asking “where do these intuitions come from?” The metaphysical realists say “they are truths of reason, underwritten by the non-natural essence of rationality itself”. The naturalists say: “these intuitions were transmitted to you via culture and genetics, itself subject to aeons of evolutionary pressure”. I side with the naturalists, despite all the best arguments for non-naturalism (to my mind, they’re mostly bad!).

One way to think about the 21st century predicament is that we usually learn via trial and error and selection pressures, but this dynamic in a world with modern technology seems unlikely to go well.