[Edits on March 10th for clarity, two sub-sections added]

Watching what is happening in the world -- with lots of renegotiation of institutional norms within Western democracies and a parallel fracturing of the post-WW2 institutional order -- I do think we, as a community, should more seriously question our priors on the relative value of surgical/targeted and broad system-level interventions.

Speaking somewhat roughly, with EA as a movement coming of age in an era where democratic institutions and the rule-based international order were not fundamentally questioned, it seems easy to underestimate how much the world is currently changing and how much riskier a world of stronger institutional and democratic backsliding and weakened international norms might be.

Of course, working on these issues might be intractable and possibly there's nothing highly effective for EAs to do on the margin given much attention to these issues from society at large. So, I am not here to confidently state we should be working on these issues more.

But I do think in a situation of more downside risk with regards to broad system-level changes and significantly more fluidity, it seems at least worth rigorously asking whether we should shift more attention to work that is less surgical (working on specific risks) and more systemic (working on institutional quality, indirect risk factors, etc.).

While there have been many posts along those lines over the past months and there are of course some EA organizations working on these issues, it stil appears like a niche focus in the community and none of the major EA and EA-adjacent orgs (including the one I work for, though I am writing this in a personal capacity) seem to have taken it up as a serious focus and I worry it might be due to baked-in assumptions about the relative value of such work that are outdated in a time where the importance of systemic work has changed in the face of greater threat and fluidity.

When the world seems to change in rather fundamental ways, we should seriously re-examine whether intuitions and priors generated under different conditions still hold and this requires, I would contend, a more serious analytical effort.

Some stylized examples to clarify the dynamic I am positing

There are two key claims I am trying to make:

(1) Systemic interventions are becoming more important relative to surgical interventions because (a) the system-level is much more in flux than it used to be and (b) many typical interventions might depend on system-level characteristics that are becoming uncertain or cannot be taken for granted anymore.

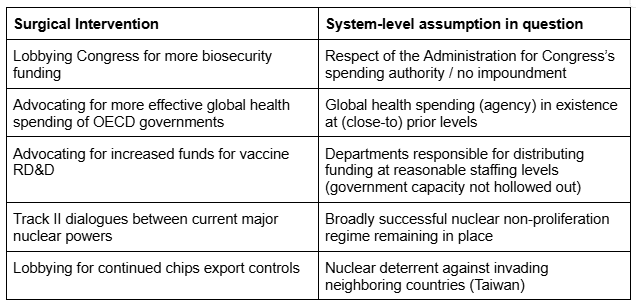

To give five stylized examples, they are meant to be illustrative not precise or necessarily the most pressing, they are selected for public salience and understandability:

In case this appears as though the system-level characteristics are myriad and unconnected, I think that’s not so – most of them can be traced to a couple of key system level qualities such as, domestically, protecting rule of law and checks and balances and, internationally, key principles of the post-WW2 order.

Given they are now much more uncertain, this undermines the effectiveness of many typical interventions (b), but it also, because they are in flux, possibly raises the importance of engaging on them (a) in absolute terms.

(2) It is quite possible that prior-based judgments on this lead us astray, especially if informed by intuitions before recent changes. This is why I think we should explore more systematically and rigorously whether the balance between surgical and systemic interventions should shift or whether changes in relative importance are not sufficient to make up for differences in tractability and neglectedness.

What next steps could be

To clarify, I am not a likely person to be able to carry this forward – I mostly wanted to raise this as an issue to evaluate for people who have or allocate research / analytical capacity with some flexibility.

Here are some ideas that I think could be valuable along the lines of what is discussed here:

- Explorations of existing models of direct and risk-factor work (e.g. Ord’s model from Precipice) to see whether current shifts plausibly seem relevant updates in favor of more systemic work

- Systematic investigations by major EA(-adjacent) research orgs on those topics; e.g. work on institutional quality that is informed by recent developments (a lot of EA work on institutions seems to be about marginal improvements, such as different voting rules, under overall very stable institutional conditions; not “meeting the moment” of a time where many institutions and norms are questioned to a degree unparalleled for decades)

- Deep dives on 80k podcast on what is happening in the US; and what is happening with regards to geopolitics and how these changes might affect things EAs care about

I agree that "systemic change" (broadly speaking) seems highly intractable for EA and that it does not seem to be that neglected outside of EA.

However, one possible advantage to this lack of neglectedness is that there are probably plenty of people already working on, or interested in, some forms of systemic change who are already sympathetic to EA ideas but don't know how to translate that into action. A lot of those people may also be mid-career, like me.

EA might be able to play a useful coordination role between such practitioners and publicise ideas that could improve their effectiveness with relatively little resources. There are plenty of common "best practices" like red-teaming, Delphi method, or reference class forecasting that can help decision-making but are still not widely used in much of government (at least in my experience, though I'm sure it will depend on the country involved). Of course, there is already a lot of material out there already on "how to be more effective" but much of it is either (1) low-quality; (2) focused on business and personal success; and/or (3) rather expensive (for courses aimed at business leaders).

Even something like mildly improving the epistemics (and perhaps morals) of people who are already in positions to shape important policies could be quite impactful, though very hard to quantify. I personally know many people in policy who genuinely want to do good but would not be willing to switch to one of EA's cause areas. It seems like EA's message to such people is basically just "earn to give", which feels like a waste. That's not to denigrate earning to give at all - it just feels like there is more potential there that EA is not tapping into.

My comments are more about EA turning to focus on system-level interventions in general, rather than to address the problems arising in this particular time of flux. But, you know, even if the best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago, it could still be worth planting today.