Here’s the funding gap that gets me the most emotionally worked up:

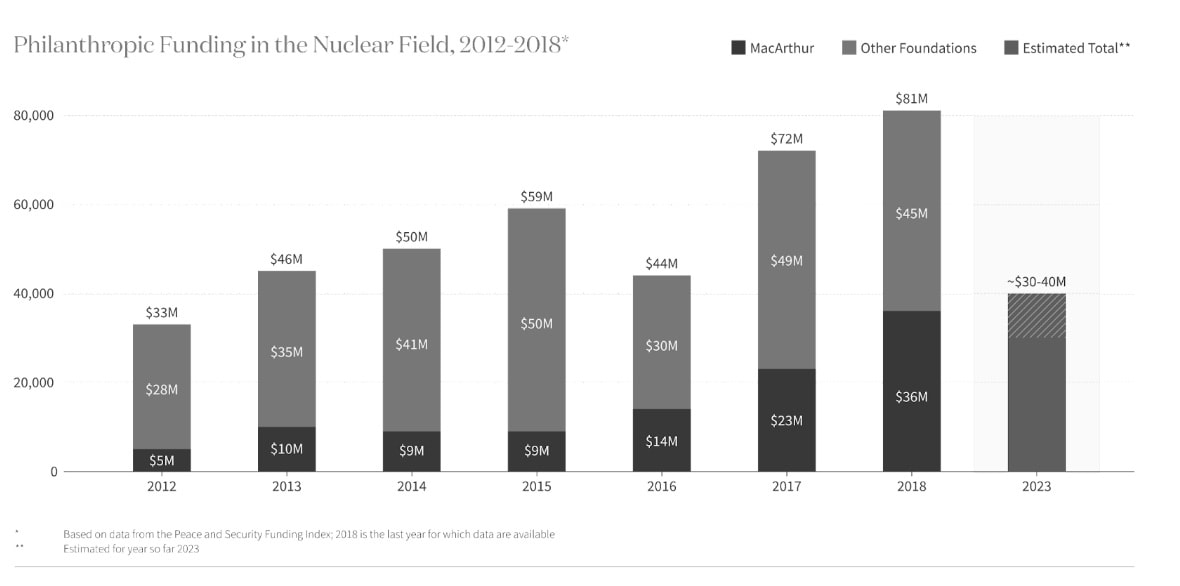

In 2020, the largest philanthropic funder of nuclear security, the MacArthur Foundation, withdrew from the field, reducing total annual funding from $50m to $30m.

That means people who’ve spent decades building experience in the field will no longer be able to find jobs.

And $30m a year of philanthropic funding for nuclear security philanthropy is tiny on conventional terms. (In fact, the budget of Oppenheimer was $100m, so a single movie cost more than 3x annual funding to non-profit policy efforts to reduce nuclear war.)

And even other neglected EA causes, like factory farming, catastrophic biorisks and AI safety, these days receive hundreds of millions of dollars of philanthropic funding, so at least on this dimension, nuclear security is even more neglected.

I agree that a full accounting of neglectedness should consider all resources going towards the cause (not just philanthropic ones), and that 'preventing nuclear war' more broadly receives significant attention from defence departments. However, even considering those resources, it still seems similarly neglected as biorisk.

And the amount of philanthropic funding still matters because certain important types of work in the space can only be funded by philanthropists (e.g. lobbying or other policy efforts you don't want to originate within a certain national government).

There's also almost no funding taking an approach more inspired by EA, which suggests there could be interesting gaps for someone with that mindset.

All this is happening exactly as nuclear risk seems to be increasing. There are credible reports that Russia considered the use of nuclear weapons against Ukraine in autumn 2022. China is on track to triple its arsenal. North Korea has at least 30 nuclear weapons.

More broadly, we appear to be entering an era of more great power conflict and potentially rapid destabilising technological change, including through advanced AI and biotechnology.

The Future Fund was going to fill this gap with ~$10m per year. Longview Philanthropy hired an experienced grantmaker in the field, Carl Robichaud, as well as Matthew Gentzel. The team was all ready to get started.

But the collapse of FTX meant that didn’t materialise.

Moreover, Open Philanthropy decided to raise their funding bar, and focus on AI safety and biosecurity, so it hasn’t stepped in to fill it either.

Longview’s program was left with only around $500k to allocate on Nuclear Weapons Policy in 2023, and has under $1m on hand now.

Giving Carl and Matthew more like $3 million (or more) a year seems like an interesting niche that a group of smaller donors could specialise in.

This would allow them to pick the low hanging fruit among opportunities abandoned by MacArthur – as well as look for new opportunities, including those that might have been neglected by the field to date.

I agree it’s unclear how tractable policy efforts are here, and I haven’t looked into specific grants, but it still seems better to me to have a flourishing field of nuclear policy than not. I’d suggest talking to Carl about the specific grants they see at the margin (carl@longview.org).

I’m also not sure, given my worldview, that this is even more effective than funding AI safety or biosecurity, so I don’t think Open Philanthropy is obviously making a mistake by not funding it. But I do hope someone in the world can fill this gap.

I’d expect it to be most attractive to someone who’s more sceptical about AI safety, but agrees the world underrates catastrophic risks (or reduce the chance of all major cities blowing up for common sense reasons). It could also be interesting as something that's getting less philanthropic attention than AI safety, and as something a smaller donor could specialise in and play an important role in. If that might be you, it seems well worth looking into.

If you’re interested, you can donate to Carl and Matthew’s fund here:

If you have questions or are considering a larger grant, reach out to: carl@longview.org

To learn more, you might also enjoy 80,000 Hours’ recent podcast with Christian Ruhl.

This was adapted from a post on benjamintodd.substack.com. Subscribe there to get all my posts.

In 2020, we at SoGive were excited about funding nuclear work for similar reasons. We thought that the departure of the MacArthur foundation might have destructive effects which could potentially be countered with an injection of fresh philanthropy.

We spoke to several relevant experts. Several of these were with (unsurprisingly) philanthropically funded organisations tackling the risks of nuclear weapons. Also unsurprisingly, they tended to agree that donors could have a great opportunity to do good by stepping in to fill gaps left by MacArthur.

There was a minority view that this was not as good an idea as it seemed. This counterargument was MacArthur had left for (arguably) good reasons. Namely that after throwing a lot of good money after bad, they had not seen strong enough impact for the money invested. I understood these comments to be the perspectives of commentators external to MacArthur (i.e. I don't think anyone was saying that MacArthur themselves believed this, and we didn't try to work out whether MacArthur themselves believed this).

Under this line of thinking, some "creative destruction" might be a positive. On the one hand, we risk losing some valuable institutional momentum, and perhaps some talented people. On the other hand, it allows for fresh ideas and approaches.

Thanks that's helpful background!

I agree tractability of the space is the main counterargument, and MacArthur might have had good reasons to leave. Like I say in the post, I'd suggest people think about this issue carefully if you're interested in giving to this area.

It's worth separating two issues:

The Foundation had long been a major funder in the field, and made some great grants, e.g. providing support to the programs that ultimately resulted in the Nunn-Lugar Act and Cooperative Threat Reduction (See Ben Soskis's report). Over the last few years of this program, the Foundation decided to make a "big bet" on "political and technical solutions that reduce the world’s reliance on highly enriched uranium and plutonium" (see this 2016 press release), while still providing core support to many organizations. The fissile materials focus turned out to be badly-timed, with Trump's 2018 withdrawal from the JCPOA and other issues. MacArthur commissioned an external impact evaluation, which concluded that "there is not a clear line of sight to the existing theory of change’s intermediate and long-term outcomes" on the fissile materials strategy, but not on general nuclear security grantmaking ("Evaluation efforts were not intended as an assessment of the wider nuclear field nor grantees’ efforts, generally. Broader interpretation or application of findings is a misuse of this report.")

Often comments like the ones Sanjay outlined above (e.g. "after throwing a lot of good money after bad, they had not seen strong enough impact for the money invested") refer specifically to the evaluation report of the fissile materials focus.

My understanding is that the Foundation's withdrawal from the field as a whole (not just the fissile materials bet of the late 2010s) coincided with this, but was ultimately driven by internal organizational politics and shifting priorities, not impact.

I agree with Sanjay that "some 'creative destruction' might be a positive," but I think that this actually makes it a great time to help shape grantees' priorities to refocus the field's efforts back on GCR-level threats, major war between the great powers, etc. rather than nonproliferation.

For more on philanthropy's role in nuclear non-proliferation, see:

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/2021/02/05/philanthropy_nuclear_nonproliferation_and_threat_reduction.pdf

-BJS

It seems like you might be under-weighing the cumulative amount of resources - even if you have some pretty heavy decay rate (which it's unclear you should -- usually we think of philanthropic investments compounding over time), avoiding nuclear war was a top global priority for decades, and it feels like we have a lot of intellectual and policy "legacy infrastructure" from that.

I agree people often overlook that (and also future resources).

I think bio and climate change also have large cumulative resources.

But I see this as a significant reason in favour of AI safety, which has become less neglected on an annual basis recently, but is a very new field compared to the others.

Also a reason in favour of the post-TAI causes like digital sentience.

I think Oppenheimer was a missed opportunity to raise money for the space. I would have liked it if Universal had pledged to donate 10% of their profits from the film to organizations advancing nuclear security.

Hot-take: I'd likely be less excited about people with decades in the field vs. new blood given that things seem stuck.

I'd also be interested in that. Maybe worth adding that the other grantmaker, Matthew, is younger. He graduated in 2015 so is probably under 32.

Or you might like to look into Christian's grantmaking at Founders Pledge: https://80000hours.org/after-hours-podcast/episodes/christian-ruhl-nuclear-catastrophic-risks-philanthropy/

Hi Ben,

I would be curious to understand why you continue to focus exclusively on philanthropic funding. I think a 100 % reduction in philantropic funding would only be a 1.16 % (= 0.047/4.04) relative reduction in total funding:

Focussing on a large relative reduction of a minor fraction of the funding makes it look like neglectedness increased a lot, but this is not the case based on the above. I think it is better to consider spending from other sources because these also contribute towards decreasing risk. In addition, I would not weight spending by cost-effectiveness (and much less give 0 weight to spending not aligned with effective altruism[1]), as this is what one is trying to figure out when using spending/neglectedness as an heuristic.

More importantly, I think you had better focus on assessing cost-effectiveness of representative promising interventions rather than funding:

Likewise for the other 4 80,000 Hours' most pressing problems. For example, I assume the funding of and number of people working on AI safety is pretty sensible to what is considered safety instead of capabilities, and it looks like there is not a clear distiction between the 2.

Christian Ruhl estimated that doubling nuclear risk reduction spending (which he mentions was 32.1 M$ in 2021) would save a life for 1.55 k$, which corresponds to a cost-effectiveness around 3.23 (= 5/1.55) times that of GiveWell's top charities. I think corporate campaigns for chicken welfare are 1.44 k times as cost-effective as GiveWell's top charities, and therefore 446 (= 1.44*10^3/3.23) times as cost-effective as what Christian got for doubling nuclear risk reduction spending.

I think it makes sense to evaluate interventions which aim to decrease nuclear risk in terms of lives saved (or similar) instead of reductions in extinction risk:

I do not think you are doing this here, but I seem to recall cases where only the amount of spending coming from sources aligned with effective altruism was highlighted.

I don't focus exclusively on philanthropic funding. I added these paragraphs to the post to clarify my position:

I'd add that if if there's almost no EA-inspired funding in a space, there's likely to be some promising gaps by someone applying that mindset.

In general, it's a useful approximation to think of neglectedness as a single number, but the ultimate goal is to find good grants, and to do that it's also useful to break down neglectedness into different types of resources, and consider related heuristics (e.g. that there was a recent drop).

--

Causes vs. interventions more broadly is a big topic. The very short version is that I agree doing cost-effectiveness estimates of specific interventions is a useful input into cause selection. However, I also think the INT framework is very useful. One reason is it seems more robust. Another reason is that in many practical planning situations that involve accumulating expertise over years (e.g. choosing a career, building a large grantmaking programme) it seems better to focus on a broad cluster of related interventions.

E.g. you could do a cost-effectiveness estimate of corporate campaigns and determine ending factory farming is most cost-effective. But once you've spent 5 years building career capital in that factory farming, the available interventions or your calculations about them will likely very different.

Thanks for clarifying, Ben!

Agreed, although my understanding is that you think the gains are often exagerated. You said:

Again, if the gain is just a factor of 3 to 10, then it makes all sense to me to focus on cost-effectiveness analyses rather than funding.

Agreed. However, deciding how much to weight a given relative drop in a fraction of funding (e.g. philanthropic funding) requires understanding its cost-effectiveness relative to other sources of funding. In this case, it seems more helpful to assess the cost-effectiveness of e.g. doubling philanthropic nuclear risk reduction spending instead of just quantifying it.

The product of the 3 factors in the importance, neglectedness and tractability framework is the cost-effectiveness of the area, so I think the increased robustness comes from considering many interventions. However, one could also (qualitatively or quantitatively) aggregate the cost-effectiveness of multiple (decently scalable) representative promising interventions to estimate the overall marginal cost-effectiveness (promisingness) of the area.

I agree, but I did not mean to argue for deemphasising the concept of cause area. I just think the promisingness of areas had better be assessed by doing cost-effectiveness analyses of representative (decently scalable) promising interventions.

To clarify, the estimate for the cost-effectiveness of corporate campaigns I shared above refers to marginal cost-effectiveness, so it does not directly refer to the cost-effectiveness of ending factory-farming (which is far from a marginal intervention).

My guess would be that the acquired career capital would still be quite useful in the context of the new top interventions, especially considering that welfare reforms have been top interventions for more than 5 years[1]. In addition, if Open Philanthropy is managing their funds well, (all things considered) marginal cost-effectiveness should not vary much across time. If the top interventions in 5 years were expected to be less cost-effective than the current top interventions, it would make sense to direct funds from the worst/later to the best/earlier years until marginal cost-effectiveness is equalised (in the same way that it makes sense to direct funds from the worst to best interventions in any given year).

Open Phil granted 1 M$ to The Humane League's cage free campaigns in 2016, 7 years ago. Saulius Šimčikas' analysis of corporate campaigns looks into ones which happened as early as 2005, 19 years ago.

Where is that image from? Is there a colour version? I might share it if there were.

https://www.macfound.org/media/article_pdfs/nuclear-challenges-synthesis-report_public-final-1.29.21.pdf[16].pdf

Executive summary: Despite the increasing risks of nuclear war, philanthropic funding for nuclear security has significantly decreased, presenting a critical funding gap that smaller donors could potentially fill.

Key points:

This comment was auto-generated by the EA Forum Team. Feel free to point out issues with this summary by replying to the comment, and contact us if you have feedback.

Thank you for drawing attention to this funding gap! Really appreciate it